Archive:SDG cross-cutting issues - COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic: detecting impacts and monitoring the recovery

Data extracted in April 2022.

Planned article update: June 2023.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2022 edition’. This report is the sixth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

Full article

The COVID-19 pandemic: detecting impacts and monitoring the recovery

The still ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on every aspect of life worldwide, from public health, economic and social stability to the environment. It affects the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs broadly, influencing all three dimensions of sustainability and threatening the achievement of the global goals. While the pandemic’s full-scale effects remain to be seen, data collected by Eurostat and published in the European Statistical Recovery Dashboard provide some indications of how COVID-19 and the related contingency measures are affecting the EU in its attempts to achieve the SDGs. In order to further monitor the situation, Eurostat has set up a dedicated section on COVID-19.

The analysis in this chapter is done in the SDG monitoring context, using breakdowns of the EU SDG indicators as well as short-term indicators such as quarterly greenhouse gas emissions for illustrating the environmental effects of the lockdown. As 2022 is the European Year of Youth, with the aim of building a greener, more inclusive and digital future, the impact of the pandemic on young people is highlighted.

Vaccination campaign helped to reduce infection and mortality rate linked to COVID-19 in 2021

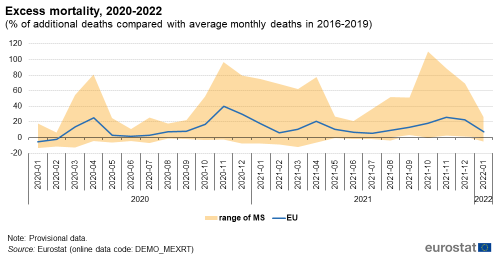

With more than 128 million COVID-19 cases in the EU and more than a million deaths linked to the virus [1], public health concerns (SDG 3) remain one of the most important effects of the pandemic. In total, from March to December 2020, 580 000 more deaths occurred in the EU compared with the same period in 2016 to 2019 [2]. In the 12 months of 2021, excess mortality went down to about 560 000 additional deaths compared with the 2016 to 2019 average [3].

While there is no confirmation that all excess deaths are due to COVID-19, there exists a clear link between excess mortality and the pandemic’s outbreak. Data show that while there were no additional deaths in 2020 compared with the 2016 to 2019 average for people under 20 years old, excess mortality reached 12.9 % and 16.6 % for people aged 60 to 79 and people aged 80 or over, respectively [4]. The situation was similar in 2021, with no additional deaths for young people and an excess mortality of 14.3 % (age group 60 to 74) and 9.2 % (people aged 80 or over), compared with the 2016 to 2019 average.

Despite a much higher number of detected COVID-19 cases in the EU in 2021 compared with 2020, the number of additional deaths in 2021 was lower. Wide deployment of COVID-19 vaccines in the EU Member States from the beginning of 2021 and strengthened health system capacities had a major impact in reducing fatality rates [5]. By April 2022, three-quarters of the total EU population were vaccinated with at least one dose, 73 % with two doses and a bit more than half had received a booster [6].

Changes in the mortality conditions also had an impact on overall life expectancy in the EU, which decreased by 0.9 years, from 81.3 years in 2019 to 80.4 years in 2020. The change was slightly stronger for men (– 1.0 years) than for women (– 0.8 years). Life expectancy at age 65 also decreased by about a year in 2020 [7].

The COVID-19 pandemic also had a profound impact on mental health. Multiple studies across countries show that symptoms of anxiety and depression increased throughout the pandemic [8]. Young people’s mental health was disproportionally affected by the COVID-19 crisis [9] as risk factors such as unemployment or lower income are more prevalent in this age group. In 2019, 6.0 % of people aged 15 to 24 had symptoms of depression, compared with 7.0 % for the total population in the EU [10]. While there is no EU-level data available for 2020 and 2021, data from Belgium, France and the United States suggest that in March 2021 the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression among young people had doubled compared with before the crisis and was considerably higher than in the general population [11].

Source: Eurostat (demo_mexrt)

Inflation in the EU on the rise since early 2021

Following the lockdown measures put in place by EU Member States in order to halt the spread of the virus, the EU’s economy (SDG 8) showed negative trends in 2020. Real GDP per capita dropped by 6.0 % in 2020 compared with 2019. Industrial production [12] (SDG 12) decreased by 7.4 % [13] and EU imports from other countries (SDG 17) fell by 11.5 % in 2020 compared with 2019 [14].

However, by 2021 the economic indicators had bounced back to almost pre-pandemic levels. Starting from the second quarter of 2021, GDP in the EU had been increasing, which resulted in an annual growth of real GDP per capita by 5.4 % in 2021 compared with 2020. Industrial production returned to pre-pandemic values by the end of 2020 and did not fluctuate significantly throughout 2021, leading to an annual increase of 8.1 % in 2021 compared with the previous year;% [15]. Similarly, extra-EU imports increased by 23.4 % from 2020 to 2021 [16].

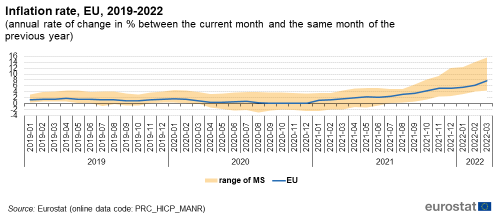

While many economic indicators have shown positive trends, the inflation rate has been on the rise in the EU since the beginning of 2021, increasing from 0.2 % in December 2020 to 7.8 % in March 2022 [17]. This led to an annual inflation rate of 2.9 % in 2021 compared with 0.7 % in 2020 [18]. This was a result of rising energy prices leading to increased consumer prices, global supply chain disruptions, reopening of the service sector and monetary and fiscal stimulus [19]. The increase in the inflation rate has been particularly strong for energy, including electricity, gas, liquid and solid fuels and heat energy [20]. As a result, food and housing sectors (including electricity, gas and other fuels) experienced the highest inflation in 2021. The elevated inflation might weigh on purchasing power, potentially pushing more people towards poverty.

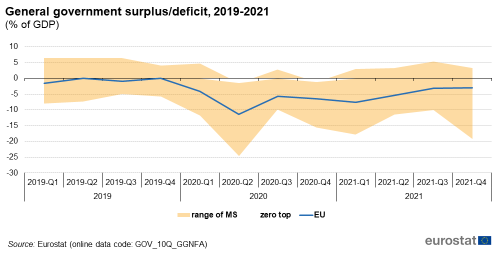

Throughout the pandemic, government measures aimed at mitigating the economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in the EU budget deficit, which reached a high of 11.4 % of GDP in the second quarter of 2020 (see Figure 3). The economic recovery of 2021 and the unwinding of the emergency support measures [21], however, helped to decrease the deficit to 2.9 % of GDP by the fourth quarter of 2021. After peaking at 92.3 % of the EU’s GDP in the first quarter of 2021, the EU’s general government gross debt to GDP ratio (SDG 17) dropped to 88.2 % by the fourth quarter of the same year, which is still higher than the pre-pandemic level of 77.5 % in the fourth quarter of 2019 [22].

Source: Eurostat (PRC_HICP_MANR)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10q_ggnfa)

The EU’s labour market is recovering after being hit by the COVID-19 pandemic

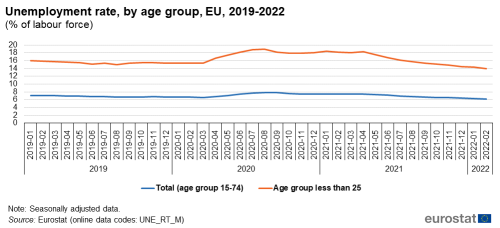

Measures introduced at the EU level [23] and by the EU Member States cushioned the most negative effects of the pandemic on the EU’s labour market. Thanks to that, the labour market situation in the EU in general has recovered to the pre-pandemic levels. However, young people were among the most affected by the pandemic because they more often work on temporary contracts than older age groups (SDG 8). In addition, they were most affected by the prolonged closing of schools in many Member States.

After a 1.9 percentage point drop in the second quarter of 2020, the total employment rate of the population aged 20 to 64 had been gradually increasing and reached 74.0 % by the fourth quarter of 2021 — the highest value observed since 2019. As a result of this strong recovery, the annual employment rate for the total population reached 73.1 % in 2021, exceeding its pre-pandemic level. Following similar trends as the employment rate, the total unemployment rate (age group 15 to 74) also peaked at 7.8 % in August 2020, before falling to 6.2 % in March 2022, which was even lower than the values observed before the pandemic. The unemployment rate for young people aged 15 to 24 increased more sharply than the total rate, reaching 18.9 % in August 2020. However, by March 2022 it had fallen back to 14.0 %, which was below the pre-pandemic level but still more than twice the total rate. In 2021, the annual unemployment rate was 7.0 % for the age group 15 to 74 and 16.6 % for young people aged 15 to 24 [24].

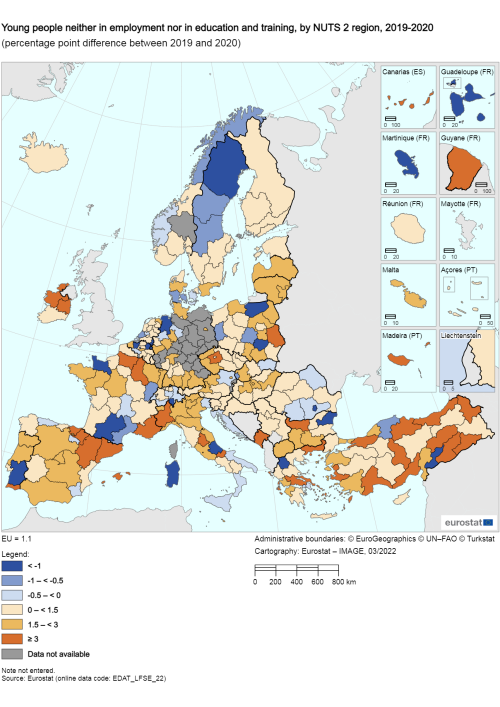

The share of young people aged 15 to 29 neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET) increased from 12.9 % in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 15.0 % in the second quarter of 2020. Thus, even at the peak of the COVID-19 crisis, the NEET rate was still lower than during the years following the financial crisis in 2009 to 2015. Moreover, already by the fourth quarter of 2021, the NEET rate had dropped to 12.7 %, which is the lowest quarterly value observed since 2009 and corresponds to almost 9 million young people. This resulted in an annual NEET rate of 13.1 % in 2021, 0.5 percentage points higher than in 2019.

When segregated by sex (SDG 5), data show there were no significant differences between men and women in terms of reduced employment or increased unemployment in the EU in 2020. The gender employment gap has slightly narrowed since the beginning of the pandemic, reaching 10.6 percentage points in the fourth quarter of 2021, compared with 11.2 percentage points at the end of 2019. However, during the pandemic women experienced a steeper fall in working hours than men due to differences in the representation of women and men in sectors and occupations affected by the crisis, gender differences in the use of telework, and the fact that women took on the larger share of care responsibilities [25]

Despite the cushioning effect of public measures, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected different population groups unevenly. Migrants, Roma and other marginalised communities and people with a minority ethnic background, persons with disabilities, workers with low skills or with temporary contracts and the self-employed were disproportionally hit by the pandemic and the halt of economic activities [26].

Source: Eurostat (une_rt_m)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_22)

Positive effects of lockdown measures on the EU’s environment

The COVID-19 crisis and the related lockdown measures resulted in a short-term improvement in some indicators that are used as proxies to monitor health of the environment, such as energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (SDG 13 and SDG 7). At the same time, there is evidence of adverse effects of the pandemic on the environment (SDG 12 and SDG 15) in the form of increased pollution from single-use plastics (such as masks, gloves and take-away food containers) [27].

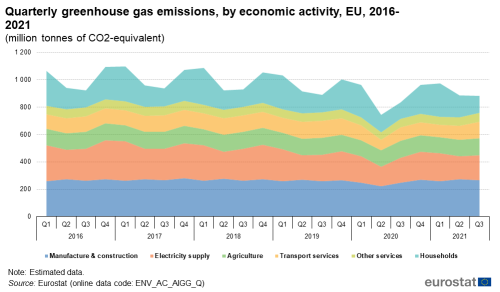

Restrictions on many social and economic activities imposed due to lockdown measures led to a drop in energy consumption in 2020 (SDG 7). This is illustrated by the trends in electricity consumption, which decreased by 12.8 % in April 2020 compared with April 2019. However, as Figure 5 shows, this fall seems to have been a one-time effect that did not change the overall pattern, since by 2021 electricity consumption was almost back to pre-pandemic levels.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, transport — a key source of GHG emissions — has been one of the most severely affected sectors. This is, for example, illustrated by the number of commercial air flights, which dropped by 91.2 % in April 2020 compared with April 2019. In March 2022, air traffic still remained 26.6 % lower than in the same month of 2019 (SDG 9).

Together with decreases in other economic activities, this reduction in transport led to an 18.9 % drop in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the second quarter of 2020 compared with the same quarter of 2019. GHG emissions in transport services as well as households’ emissions experienced the strongest declines, by 35.8 % and 22.3 %, respectively. Following the economic recovery in 2021, GHG emissions also increased again and in the third quarter of 2021 were 5.7 % higher than a year earlier. However, in the three first quarters of 2021 GHG emissions were still lower than before the pandemic, indicating that despite the effect of the economic rebound between the second quarters of 2020 and 2021 the EU’s GHG emissions continue their long-term reduction trend [28]

Source: Eurostat (nrg_cb_eim)

Source: Eurostat (ENV_AC_AIGG_Q)

Conclusions and outlook

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, progress towards the SDGs in the EU was uneven, with some areas requiring more focused attention and action. The pandemic has made achieving the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs even more challenging, both for the EU and globally [29]. Increased mortality and short- and long-term health implications of COVID-19 are the most obvious negative consequences of the pandemic. The lockdown measures put in place to halt the spread of the virus negatively influenced the EU’s economy and labour market, which in turn put additional pressure on vulnerable population groups. Even though some positive effects on energy use and GHG emission are visible, the data suggest these were temporary and that consumption patterns are starting to return to pre-crisis levels.

On the other hand, the EU’s response [30] to the crisis shows that it has been possible to mitigate the economic and social impacts of the pandemic. Already in the third quarter of 2020, many economic and labour market indicators showed signs of recovery and by 2021 they had almost reached their pre-pandemic levels.

The long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the EU economy, labour market, education and poverty, as well as on environmental issues, however, remain to be seen. With more data becoming available, future SDG monitoring reports might present a more detailed and nuanced picture about the consequences of the pandemic.

Direct access to

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages, can be found in the introduction of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2022 edition’.

Further reading on COVID-19

- EEA (2021), Air Quality in Europe 2021, EEA Report No 15/2021, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- EEA (2021), COVID-19: lessons for sustainability? EEA Briefing No. 20/2021, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Environment Agency (2020), COVID-19 and the environment: explore what we know.

- European Environment Agency (2021), Briefing: COVID-19 and Europe’s environment: impacts of a global pandemic.

- European Commission (2021), EU research and innovation in action against the coronavirus.

- Eurostat (2022), Excess mortality down to +7% in January and February.

Further data sources on COVID-19

Notes

- ↑ By 14 April 2022, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/cases-2019-ncov-eueea

- ↑ Eurostat (2021), 580 000 excess deaths between March and December 2020.

- ↑ Source: own calculations based on Eurostat (demo_r_mwk_20). Data refer to EU excluding Ireland.

- ↑ Source: own calculations based on Eurostat (demo_r_mwk_20). Data refer to EU excluding Ireland.

- ↑ OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- ↑ European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2022), COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (demo_mlexpec).

- ↑ OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, p.5.

- ↑ OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, p.56.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (hlth_ehis_mh1i).

- ↑ OECD (2021), Supporting young people’s mental health through the COVID-19 crisis, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris.

- ↑ Industrial production covers the following sectors: mining and quarrying; manufacturing; electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (sts_inpr_a)).

- ↑ Source: own calculations based on Eurostat (ext_lt_intertrd).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (sts_inpr_a)).

- ↑ Source: own calculations based on Eurostat (ext_lt_intertrd).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (PRC_HICP_MANR).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (PRC_HICP_AIND).

- ↑ European Commission (2021), European Economic Forecast, Autumn 2021, Institutional Paper 160, p. 14.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (PRC_HICP_MANR).

- ↑ European Commission (2021), European Economic Forecast, Autumn 2021, Institutional Paper 160, p. 34.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (GOV_10Q_GGDEBT).

- ↑ European Commission (2022), Coronavirus response.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (une_rt_a).

- ↑ European Commission (2021), Proposal for a Joint Employment Report 2022, COM(2021) 743 final, Brussels.

- ↑ European Commission (2021), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2021.

- ↑ EEA (2021), Impacts of COVID-19 on single-use plastic in Europe’s environment.

- ↑ Eurostat (2021), Eurostat releases for the first time estimates of quarterly EU greenhouse gas emissions.

- ↑ UN (2020), The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020; and SDSN and IEEP (2020), The 2020 Europe Sustainable Development Report: Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainable Development Solutions Network and Institute for European Environmental Policy, Paris and Brussels.

- ↑ European Commission (2022), Coronavirus response.