SDG 8 - Decent work and economic growth

Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

Data extracted in April 2024.

Planned article update: June 2025.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’. This report is the eighth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 8 recognises the importance of sustained economic growth and high levels of economic productivity for the creation of well-paid quality jobs and calls for opportunities for full employment and decent work for all.

Full article

Decent work and economic growth in the EU: overview and key trends

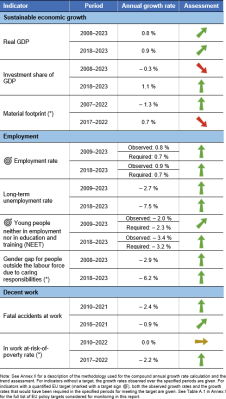

Sustainable economic growth and decent work are vital for the development and prosperity of European countries and the wellbeing and personal fulfilment of individuals. Monitoring SDG 8 in an EU context involves looking into trends in the areas of sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work. As illustrated by the figure on the right, the EU has made quite strong progress towards SDG 8 over the assessed five-year period. The EU’s economy has grown, which in turn has improved the EU’s overall employment situation. The EU is thus on track to meet its 2030 target for the overall employment rate and the complementary target on the share of young people neither in employment nor in education or training. Additionally, working conditions have also improved, with fewer fatal work accidents and fewer people being affected by in-work poverty. However, economic growth went hand in hand with an increase in the EU’s material footprint over the assessed five-year period.

Sustainable economic growth

While economic growth is an important driver of prosperity and society’s well-being, it can also harm the environment it depends on. To ensure the well-being of future generations, the EU has adopted a new growth strategy, the European Green Deal, to transform the Union into a modern, resource-efficient, fair and competitive economy. The indicators selected to monitor this objective show that over the assessed five-year period, Europeans have generally enjoyed continuous economic growth. However, this growth came hand in hand with an increase in the EU’s material footprint.

Real GDP per capita has grown moderately over the past five years

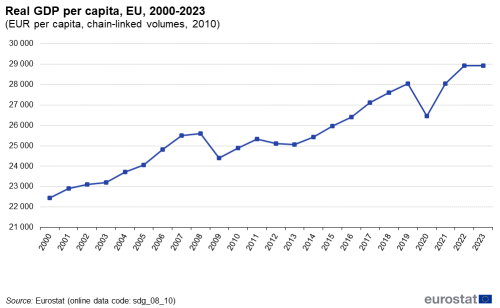

Citizens’ living standards depend on the performance of the EU economy, which can be measured using several indicators. One of these is growth in gross domestic product (GDP). Although GDP is not a measure of welfare, it gives an indication of an economy’s potential to satisfy people’s needs and its capacity to create jobs. It can also be used to monitor economic development.

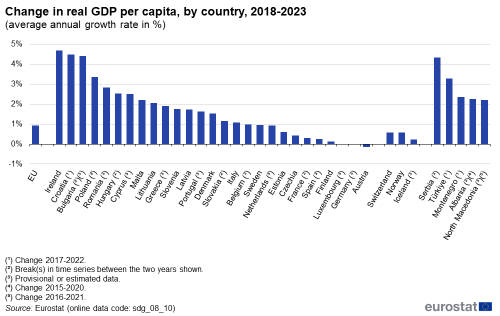

Real GDP per capita (GDP adjusted for inflation) in the EU saw strong and continuous growth of 2.0 % per year on average between 2014 and 2019. In 2020, the economy was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in a 5.7 % contraction of real GDP compared with 2019. Nevertheless, the economy rebounded from the recession in the two following years, and real GDP per capita reached EUR 28 940 (based on data chain-linked to 2010) in 2022. This growth was mostly driven by a spending spree that came with an easing of COVID-19 containment measures [1]. In 2023, however, GDP per capita remained at the same level of EUR 28 940 as in the previous year. This is likely to be connected to the stagnation of consumption and investment, and a still ongoing post-pandemic rebalancing of supply and demand [2]. Over the short-term period between 2018 and 2023, the EU’s real GDP per capita grew by 0.9 % per year on average. Looking ahead, GDP in the EU is projected to expand by 1.0 % and 1.6 % in 2024 and 2025, respectively [3].

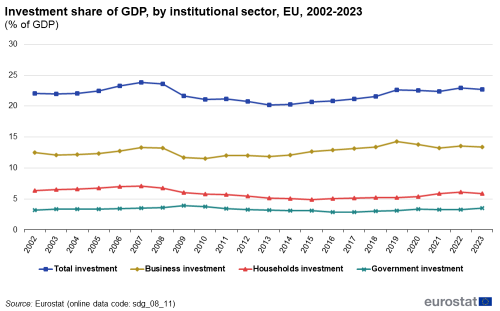

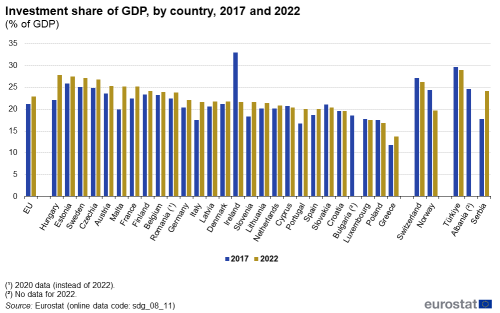

Investment is another indicator of economic growth as it enhances an economy’s productive capacity. In 2023, the total investment share of GDP in the EU was 22.7 %. Despite a 1.1 percentage points increase since 2018, the trend stagnated between 2019 and 2023. Businesses were the biggest investors in 2023, with an investment share in GDP of 13.4 %, followed by households with 5.8 % and governments with 3.5 %. The investment share of households has been slowly growing since 2016, disregarding a 0.3 percentage points dip in 2023, but still remains below the levels before the 2008 financial crisis. This is most likely because household investment consists mainly of the purchase of dwellings. Government investment has followed a counter-cyclical pattern, increasing during both the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 crisis in 2020.

The EU’s material footprint has increased since 2017

Economic growth helps to satisfy peoples’ material needs, which, in turn, can put pressure on the environment. The EU, therefore, aims to lower this pressure by reducing its material footprint. The material footprint, also referred to as raw material consumption (RMC), shows the amount of material extracted from nature, both inside and outside the EU, to manufacture or provide the goods and services consumed by EU inhabitants. In other words, it refers to the resources needed to sustain the EU’s economic and social activities.

The EU’s material footprint had been growing between 2000 and 2008, before it was halted by the economic crisis. As the EU’s economy recovered, consumption started rising again, increasing by 7.6 % between 2015 and 2019. After a 4.4 % drop in 2020, which was likely to have been influenced by the economic slowdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the consumption of raw materials in the EU rose again in 2021 and 2022, by 3.7 % and 1.1 %, respectively. Raw material consumption in the EU has thus already risen above pre-pandemic numbers and reached 6.67 billion tonnes in 2022 – the highest level since 2012.

The EU’s total material footprint has not only increased in recent years but is also above the global average and exceeds sustainable levels of resource extraction. This means that Earth’s capacity to provide resources would be exceeded if all countries in the world were to consume resources at the same rate as the EU [4]. The EU is thus not on track to significantly reduce its material footprint, as envisioned by the European Green Deal and the 8th Environmental Action Programme. For more information on the EU’s material footprint, see the article on SDG 12 ‘Responsible consumption and production’.

Employment

Decent employment for all — including for women, people with disabilities, young people, older people, those with migrant backgrounds and other disadvantaged groups — is a cornerstone of socio-economic development. Apart from generating the resources needed for decent living standards and achieving life goals, work provides opportunities for meaningful engagement in society, which in turn promotes a sense of self-worth, purpose and social inclusion. Higher employment rates are a key condition for making societies more inclusive by reducing poverty and inequality in and between regions and social groups. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan sets a target for at least 78 % of the population aged 20 to 64 to be in employment by 2030. It also envisions the complementary ambition of at least halving the gender employment gap and decreasing the rate of young people aged 15 to 29 who are neither in employment nor in education or training (NEETs) to 9 %.

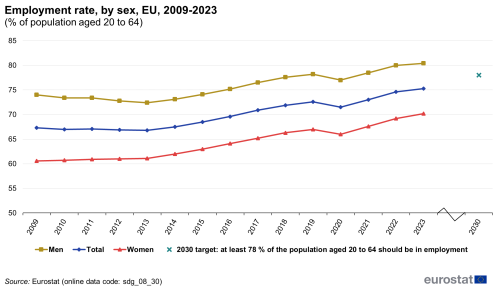

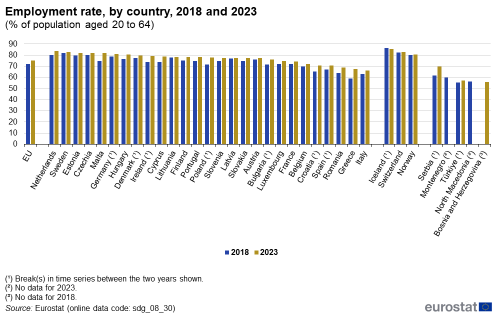

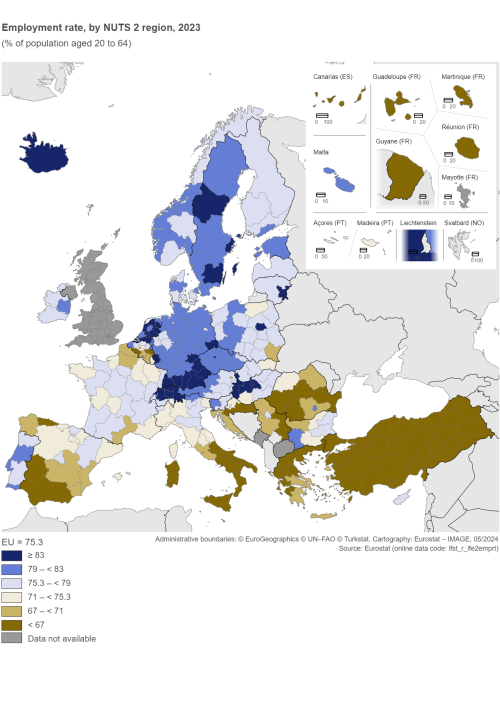

The EU’s employment rate reached a historic high in 2023

The EU employment rate has shown steady growth in both the long and the short term. Despite the uncertain and challenging environment caused by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the employment rate in the EU reached a record high of 75.3 % in 2023, which is a 3.4 percentage points increase since 2018 when it amounted to 71.9 %. In the upcoming years, the slowing of economic activity is expected to weigh on the pace of the employment growth in 2024 and 2025 [5]. Nevertheless, the EU is well placed to reach its target of 78 % by 2030.

An analysis by degree of urbanisation reveals that employment rates in rural areas had been slightly higher than in cities and in towns and suburbs until 2021. In 2023, the employment rate in cities reached 75.6 %, while it was at 75.4 % in rural areas and 74.9 % in towns and suburbs [6].

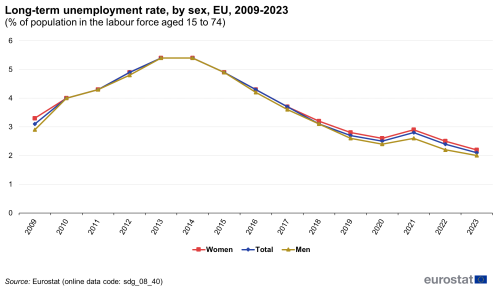

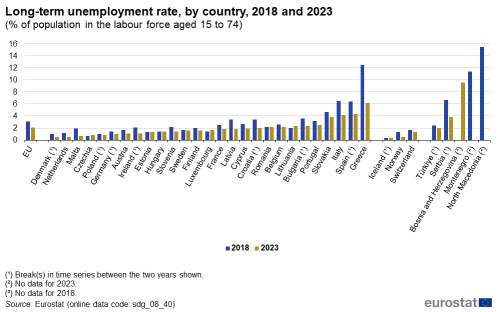

Unemployment and long-term unemployment reached all-time low in 2023

The EU’s unemployment situation has been improving almost steadily over the past decade. Between 2013 and 2023, the EU’s unemployment rate for the age group 15 to 74 decreased by 5.5 percentage points, affecting 6.1 % of the population in the labour force in 2023 — the lowest value recorded since 2009 [7]. Over the past years, city dwellers have been more affected by unemployment than those living in rural areas. In 2023, the unemployment rate in cities was 6.7 % compared with 5.3 % for rural areas [8].

Long-term unemployment usually follows the trends in unemployment, but with a delay. Being unemployed for a year or more can have long-lasting negative implications for individuals and society by reducing employability prospects, contributing to human capital depreciation, endangering social cohesion and increasing the risk of poverty and social exclusion. Beyond material living standards, it can also lead to a deterioration of individual skills and health status, thus hindering future employability, productivity and earnings.

Similar to the unemployment rate, the long-term unemployment in the EU has been declining since 2014. In 2023, the rate reached the lowest value on record, at 2.1 %, which is 1.0 percentage points below the 2018 level. The proportion of long-term unemployment in total unemployment has also decreased since 2014 and reached 35.0 % in 2023, which is 7.5 percentage points below the level observed in 2018 [9].

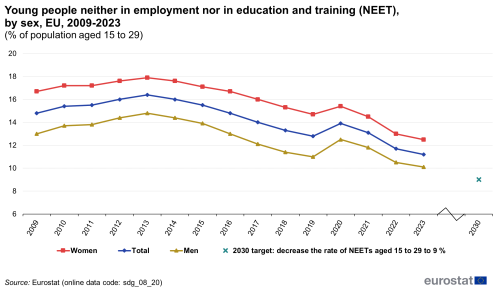

The situation for young people in the labour market is improving

The labour market situation of young people has been improving steadily since 2014, disregarding the pandemic-related drop. By 2023, the youth employment rate, referring to people aged 20 to 24 years, reached 54.2 %. While this is the highest level recorded, it is significantly lower than for other age groups [10]. The relatively low employment rate for people aged 20 to 24 can be explained by the fact that many people at this age are in education and thus not part of the labour force. In addition, youth unemployment was significantly higher than for older age groups. Despite a strong 10.5 percentage point decrease in youth unemployment since 2013, 12.9 % of 20- to 24-year-olds who were part of the labour force were unemployed in 2023 [11].

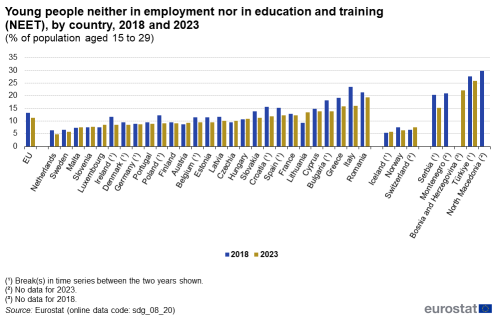

Young people not engaged in employment nor in education and training (NEET) are among the most vulnerable groups in the labour market. Over the long term they may fail to gain new skills and suffer from erosion of competences, which in turn might lead to a higher risk of labour market and social exclusion. To improve the labour market situation of young people, the EU set a complementary target of decreasing the NEET rate to 9 % by 2030.

The NEET rate for 15- to 29-year-olds in the EU had been improving since 2013 and reached 11.2 % in 2023, which was the lowest value recorded. If this positive trend continues, the EU is well placed to reach its NEET rate target of 9 % by 2030. Since 2009, the NEET rate in rural areas and in towns and suburbs had been higher than in cities. By 2023, it amounted to 12.3 % in rural areas and 11.7 % in towns and suburbs, compared with a rate of 10.3 % in cities [12].

The participation of women in the labour market is growing, but gender differences persist

The employment rate of women in the EU has been increasing since 2009 and reached a new high of 70.2 % in 2023. The gender employment gap, however, continues to persist, despite narrowing by 3.2 percentage points since 2009. In 2023, it amounted to 10.2 percentage points, despite women becoming increasingly well-qualified and even outperforming men in terms of educational attainment (see the article on SDG 5 ‘Gender equality’).

Inflexible work-life-balance options and underdeveloped care services — both for childcare and long-term care of a family member — are major impediments to women remaining in or returning to work. Caring responsibilities, which include care for children and care for adults with disabilities, are more often performed by women, contributing to the gender employment gap. In 2023, 0.9 % of women in the EU aged 20 to 64 who were willing to work were outside the labour force because they were caring for children or adults with disabilities. For men, this share was 0.1 %. Caring responsibilities are also the main reason why women are opting for part-time jobs [13]. As a result, women were overrepresented in this type of employment, with 27.9 % of employed women working part-time in 2023, compared with 7.7 % of employed men [14].

Interestingly, the share of women who indicated caring responsibilities as the main reason for part-time employment in 2023 varied widely across the EU Member States, from 1.6 % in Denmark to 37.3 % in the Netherlands [15]. Similarly, the share of women working part-time varied significantly. While only 1.4 % of employed women in Bulgaria and 2.9 % in Romania performed part-time work, this was the case for 60.6 % in the Netherlands and 50.7 % in Austria in 2023 [16].

Employment opportunities are lower for people with disabilities

People with disabilities have a basic activity difficulty (such as seeing, hearing, walking or communicating) and/or a work limitation caused by a longstanding health condition and/or a basic activity difficulty. Disabilities impact people’s lives in many areas, including participation in the labour market. In 2022, the employment rate of people with disabilities at the EU level was 21.4 percentage points lower than people without disabilities. For women with disabilities, this gap was 18.9 percentage points, while for men with disabilities it was 23.3 percentage points. The degree of disability is also an important factor affecting the employment rate. At the EU level, the employment rate for people with a severe disability was 42.1 percentage points lower than for people without a disability, while for people with a moderate disability the gap was 14.5 percentage points in 2022 [17].

Decent work

For a society’s sustainable economic development and well-being it is crucial that economic growth generates not just any kind of job but ‘decent’ jobs. This means that work should deliver fair income, workplace security and social protection for families, better prospects for personal development and social integration and equality of opportunity [18]

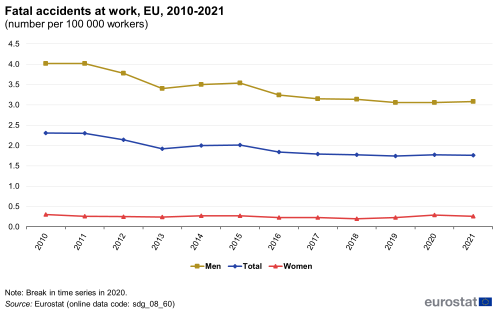

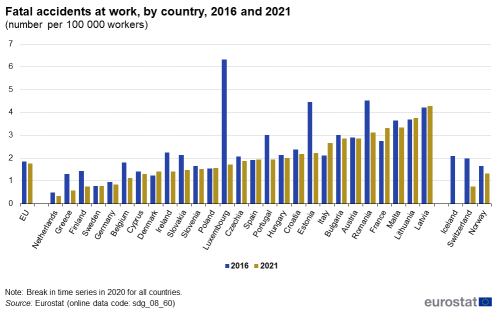

Over the past few years, work in the EU has become safer and more economically secure

A prerequisite for decent work is a safe and healthy working environment, without non-fatal and fatal accidents, occupational diseases and other work-related health problems, where risks of work-related hazardous events or exposures are minimised. Over the past few decades, the EU and its Member States have put considerable effort into ensuring high minimum requirements in occupational health and safety at work. As a result, the rate of fatal accidents at work has declined by 23.8 % since 2010, amounting to 1.76 fatalities per 100 000 employed persons in 2021. Mining and quarrying as well as construction have been especially prone to fatal accidents over the past decade, with the rate of fatal accidents at work amounting to 7.23 and 6.32 fatalities per 100 000 employed persons in 2021, respectively [19].

While there has been a significant decrease since 2010, a noticeable gender difference persists: in 2021, the incidence rate for women was only 0.26 per 100 000 persons, compared with 3.08 for men. This gender gap is due to the fact that activities with the highest incidence rates are mostly male-dominated [20].

Besides safety at work, fair income and social protection are also important components of decent work. Poverty is often associated with the absence of a paid occupation but low wages can also push some workers below the poverty line. People working part-time or on temporary contracts, low-skilled workers and non-EU born workers are especially affected by in-work poverty. In the EU, the share of the so-called ‘working poor’ (aged 18 and over) has been decreasing since 2016 and reached 8.5 % in 2022. For more information on in-work poverty, see the article on SDG 1 ‘No Poverty’.

While a fixed-term contract, part-time employment or platform work may provide greater flexibility for both employers and workers, it is not always a personal choice for an employee and can thus significantly influence their well-being. In 2023, 3.8 % of European employees aged 20 to 64 were involuntarily working on temporary contracts, corresponding to 31.1 % of all temporary employees. This share has decreased significantly over the past five years [21]. The indicator on labour transitions from temporary to permanent contracts also shows that the share of such transitions has increased since 2015, reaching 33.0 % in 2022 (based on a three-year average) [22]. Like involuntary temporary employment, the share of involuntary part-time employment in total employment in the EU also decreased, from 5.0 % in 2018 to 3.4 % in 2023 [23].

Main indicators

Real GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of economic activity and is often used as a proxy for changes in a country’s material living standards. It refers to the value of total final output of goods and services produced by an economy within a certain time period. Real GDP per capita is calculated as the ratio of real GDP (GDP adjusted for inflation) to the average population of the same year and is based on rounded figures.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_10)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_10)

The investment share of GDP measures gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) for the total economy, government and business, as well as household sectors as a percentage of GDP.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_11)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_11)

Employment rate

The employment rate is defined as the percentage of employed persons in relation to the total population. The data analysed here focus on the population aged 20 to 64. Employed persons are those who, during a reference week, worked at least one hour for pay or profit or were temporarily absent from such work. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_30)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_30)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_lfe2emprt)

Long-term unemployment rate

Long-term unemployment is measured as a percentage of the population in the labour force (which includes both employed and unemployed people) aged 15 to 74 who have been unemployed for 12 months or more. Long-term unemployment increases the risk of a person completely stopping their search for employment and falling into poverty, and has negative implications for society as a whole. People in the EU who are long-term unemployed have about half the chance of finding employment as those who are short-term unemployed [24]. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_40)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_40)

Young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET)

A considerable proportion of young people aged 15 to 29 in the EU are not employed. For some this is due to the pursuit of education and training. However, others have withdrawn from education and training as well. Those are captured by the statistics on young people who are neither in employment (meaning they are outside of the labour force or unemployed), education nor training (NEET rate). Data presented in this section stem from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_20)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_20)

Fatal accidents at work

Fatal accidents at work are those occurring during the course of employment and leading to the death of the victim within one year — commuting accidents occurring between the home and the workplace are excluded from data at EU level. The incidence rate refers to the number of accidents per 100 000 persons in employment. Data presented in this section are collected in the framework of the administrative data collection. [25] As an exception, fatal road traffic accidents at work are not included in the data from the Netherlands.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_60)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_60)

Direct access to

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’.

Further reading on decent work and economic growth

- European Commission (2023), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Commission (2024), European Economic Forecast, Spring 2024, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Commission, Women’s situation in the labour market.

- International Labour Organisation webpage on ‘decent work and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development’.

- International Labour Organisation (2024), World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2024, Geneva

- OECD (2024), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2024 Issue 1, OECD Publishing, Paris

- OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2022: Economic and Social Impacts and Policy Implications of the War in Ukraine, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- European Environment Agency (2021), Growth without economic growth.

Further data sources on decent work and economic growth

Notes

- ↑ European Commission (2022), European Economic Forecast, Autumn 2022, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 1.

- ↑ European Commission (2024), European Economic Forecast, Winter 2024, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 2.

- ↑ European Commission (2024), European Economic Forecast, Spring 2024, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 1.

- ↑ EEA (2023), Europe’s material footprint.

- ↑ European Commission (2023), European Economic Forecast, Autumn 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 3.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfst_r_ergau)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (une_rt_a)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfst_r_urgau)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (une_ltu_a)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_ergan)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_urgaed)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (edat_lfse_29)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_epgar)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_epgaed)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_epgar)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_epgaed)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (hlth_dlm200)).

- ↑ International Labour Organisation (2022), Decent work.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (hsw_n2_02)).

- ↑ Eurostat (2023), Statistics Explained: Accidents at work - statistics by economic activity.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_etgar)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_lvhl36)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_epgar) and (lfsa_epgaed)).

- ↑ European Commission (2016), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2015, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 13.

- ↑ Eurostat (2013),European Statistics on Accidents at Work (ESAW) - Summary methodology, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.