Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

Data extracted in April 2025.

Planned article update: June 2026.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2025 edition’. This report is the ninth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 5 aims to achieve gender equality by ending all forms of discrimination, violence and any harmful practices against women and girls. It also calls for the full participation of women and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making.

Gender equality in the EU: overview and key trends

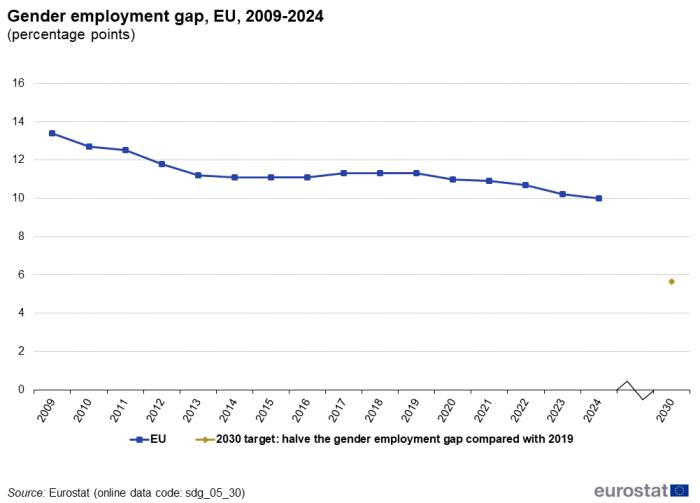

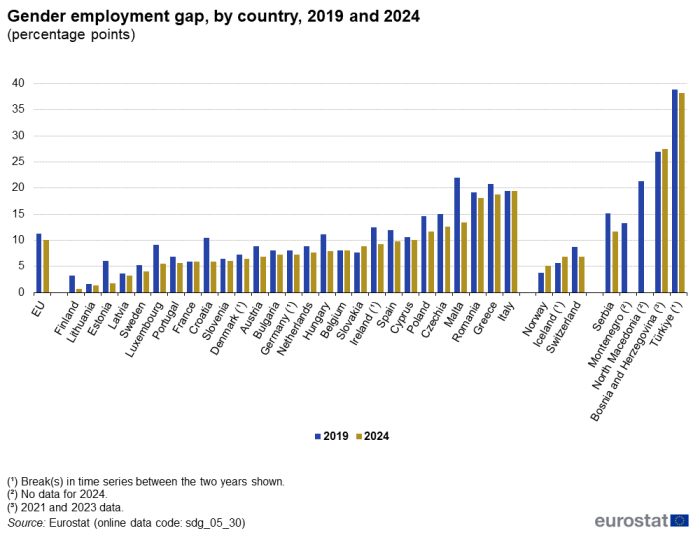

Ending all forms of discrimination against women and girls and empowering women are crucial to accelerating sustainable development in the EU. Thus, monitoring SDG 5 in an EU context focuses on the topics of gender-based violence, access to quality education, participation in employment, equal payment and a balanced representation in leadership positions. Over the assessed five-year period, the EU has made strong progress in most of these areas. The gender gaps for certain labour market-related indicators have narrowed, even though stronger progress will be needed to reach the 2030 target of halving the gender employment gap. Moreover, the share of women occupying leadership positions has increased in the EU, though a clear gap between women and men remains. The situation regarding participation in education is mixed, with the gender gap for early school leaving narrowing as men continue to fall further behind women in terms of tertiary educational attainment levels.

Gender-based violence

Gender-based violence is a brutal form of discrimination and a violation of fundamental human rights. It is both a cause and a consequence of inequalities between women and men. Physical and sexual violence against women affects their health and well-being. Moreover, it can hamper women’s access to employment and harm their financial independence and the economy overall.

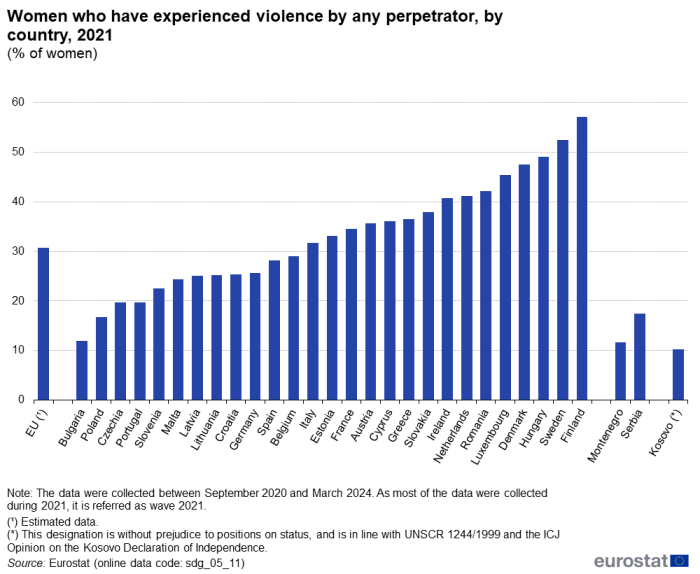

Every third woman in the EU has experienced gender-based violence during adulthood

The 2021 EU survey on gender-based violence against women [1] shows that every third woman (30.7%) in the EU experienced physical or sexual violence in adulthood. Gender-based violence was reported most frequently by women aged 18 to 29, with 34.9% having had such experiences. In comparison, 31.2% of women aged 45 to 64 and 24.2% of those aged 65 to 74 reported similar experiences. The prevalence of gender-based violence as reported in the survey varies from one country to another. The percentage of women who said they had experienced physical or sexual violence in adulthood was highest in Finland, Sweden and Hungary, at 57.1%, 52.5% and 49.1%, respectively. Furthermore, a higher share of women living in cities reported they have been affected by gender-based violence (34.0%) than women living in towns and suburbs (28.6%) or rural areas (27.3%) [2]. Women with disabilities are even more likely to experience physical and/or sexual violence, depending on the level of disability; the higher the level of disability, the higher the reported rate of physical and/or sexual violence [3]. It is important to note that the willingness of women to disclose their experiences of violence in the survey may be influenced by how such violence is perceived and tolerated within their communities.

Data from official crime statistics on intentional homicide and sexual offences show that women are much more likely to be a victim of such crimes than men. In 2022, 64 out of 100 000 women were victims of sexual assault, and 38 out of 100 000 women were victims of rape. The rates were significantly lower for men, with 11 per 100 000 men for sexual assault and 4 out of 100 000 men for rape [4]. Moreover, women are about twice as likely as men to be a victim of intentional homicide by family and relatives or their intimate partner. In 2022, 0.4 out of 100 000 women were victims of such homicide, compared with only 0.2 per 100 000 men [5]. In Western Europe this type of homicide notably increased during the pandemic [6].

The prevalence of violence varies greatly across the EU. However, caution is needed when comparing countries’ official crime statistics. Their comparability can be affected, for example, by different legal and criminal justice systems or criminal law and legal definitions such as those concerning offenders, victims or prosecutable age. Also, aspects such as the organisation and efficiency of the police, prosecution and courts or recording and reporting systems contribute to cross-country differences [7]. The limitations of comparability also include the stigma associated with disclosing cases of violence against women in certain settings and to certain people, including to interviewers. In addition, Member States that rank highest in terms of gender equality also tend to report a greater prevalence of violence against women. This may indicate a greater awareness and willingness of women in these countries to report violence to the police or to an interviewer [8].

Education

Education is a driving force for social change and a condition for achieving fundamental human rights. Equipping people with the right skills also allows them to find quality jobs and improve their chances in life and thus combat the risks of social exclusion. Economic independence also makes it easier to leave a difficult situation, such as a violent home. In education and training, it is important to eliminate gender stereotypes and promote gender balance in traditionally ‘male’ or ‘female’ fields. In general, equal access to quality education and training is thus an important foundation for gender equality and an essential element of sustainable development.

Young women outperform men in terms of education

Women overall tend to stay longer in the education system than men do. In 2024, 10.9% of men as compared with 7.7% of women aged 18 to 24 had left education and training early in the EU, having only attained lower secondary education at most. This resulted in a gender gap of 3.2 percentage points in 2024, which is 0.2 percentage points smaller than in 2018. It needs to be noted that the short-term trend since 2018 has been characterised by fluctuations in the gap of between 3.1 and 3.8 percentage points. Nevertheless, the long-term trend shows a narrowing of this gap compared with 2008, when it had amounted to 4.2 percentage points.

A major expansion in higher education systems has taken place in the EU since the early 2000’s, when the Bologna process put in motion a series of reforms to make higher education in Europe more compatible, comparable, competitive and attractive for students. As a result, the share of the population aged 25 to 34 who completed tertiary education increased steadily between 2002 and 2024. The increase was particularly strong for women, whose tertiary educational attainment rate rose from 25.3% in 2002 to 49.9% in 2024. For men, the increase was slower, from 21.0% to 38.6%. This caused the gender gap to surge almost continuously from 4.3 percentage points to 11.2 percentage points between 2002 and 2024. Nevertheless, since 2022 tertiary attainment rates have increased at the same pace for women and men, and the gender gap has consequently remained at 11.2 percentage points since then.

Employment

Ensuring high employment rates for both men and women is one of the EU’s key targets. Reducing the wide gender employment gap, which measures the difference between the employment rates of men and women aged 20 to 64, is important for equality and a sustainable economy. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan consequently includes the target of at least halving the gender employment gap by 2030 compared with 2019.

Women tend to be more highly educated than men in most EU countries. Despite this, women on average are still paid less, as evidenced by the persistent gender pay gap. One reason is that women in the EU are over-represented in low-paid sectors and under-represented in well-paid sectors. Moreover, women often adapt their working patterns to caring responsibilities, which results in lower earnings over the course of their lives and aggravates their risk of poverty and social exclusion, especially in old age, because employment and pay gaps largely influence the gender pension gap [9].

The employment rate for women continues to increase, but the EU is not on track to halving its gender employment gap by 2030

In the EU, the employment rate for women grew from 60.6% in 2009 to 70.8% in 2024. For men, the rate started from a higher value and increased more slowly, from 74.0% in 2009 to 80.8% in 2024 (see the article on SDG 8 'Decent work and economic growth' for more detailed analyses on employment rates). As a result, the gender employment gap narrowed by 3.4 percentage points between 2009 and 2024. Most of this decrease took place in the period leading up to 2014, with the gap then remaining at just over 11 percentage points until 2020, before decreasing further during the next three years. Although the drop to 10.0 percentage points in 2024 represents a new record low, it also means the proportion of working-age men in employment still considerably exceeds that of women. Moreover, the gap is not narrowing quickly enough for the EU to meet its 2030 target of at least halving the gender employment gap compared with 2019. Meeting this target would require the difference in the employment rate between men and women to be reduced to 5.7 percentage points or lower.

An analysis by degree of urbanisation shows a variation in the gender employment gap between cities, towns and suburbs, and rural areas. In 2024, the gap was smallest in cities, at 8.4 percentage points, while it amounted to 10.9 percentage points in rural areas and 11.4 percentage points in towns and suburbs [10].

The gender employment gap is considerably higher for people with children, at 16.5 percentage points for those aged 25 to 54 years. Notably, in this age group, men with children have a higher employment rate (91.9% in 2024) than men without children (83.9%). For women, the trend is the opposite, with women with children more likely to have a lower employment rate (75.4%) than women without children (80.1%) [11].

There is also a clear difference between employed women and men aged 20 to 64 when looking at the rate of part-time working. In 2024, 27.9% of employed women in this age group worked part-time, while the percentage for men was only 7.7%. This difference resulted in a gender gap of 20.2 percentage points for part-time employment. Caring responsibilities for children or for adults with disabilities were a main reason for this gap. In 2024, 27.5% of women working part-time reported caring responsibilities as the main reason for doing so, compared with only 7.1% for men [12]. The gender gap for employed persons with temporary contracts was much less pronounced, at 2.4 percentage points in 2024 (11.3% of employed women and 8.9% of employed men) [13].

During the confinement periods due to the COVID-19 pandemic, women experienced a steeper fall in working hours than men while facing an increased care burden. This further underlined the importance of enhancing access to early childhood education and care and to long-term care services to increase the labour market participation of women [14].

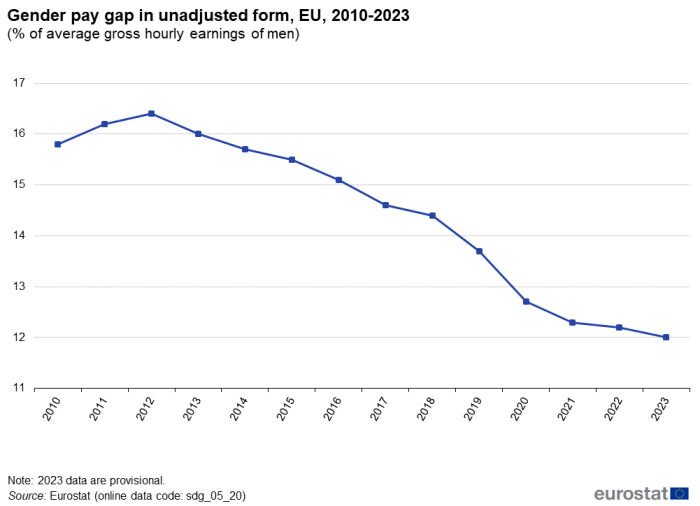

The gender pay gap in the EU continues to narrow but remains considerable

Women do not only have lower employment rates than men, they also tend to earn less. Between 2018 and 2023, the gender pay gap narrowed by 2.4 percentage points in the EU. However, in 2023, women’s gross hourly earnings in the EU were still on average 12.0% below those of men and differences between Member States vary strongly.

There are various reasons for the existence and size of the gender pay gap. A part of the difference in earnings between men and women may be explained by the ‘sectoral gender segregation’, meaning that women tend to be concentrated in the low-paying economic sectors such as education and health, whereas men tend to work more in better paid sectors such as finance and IT sectors. Similarly, the ‘occupational gender segregation’ may also explain part of the difference in earnings between men and women because men are more likely to be promoted to supervisory and management positions than women, often due to discrimination or self-restraints. The term ‘glass ceiling’ is commonly used as a metaphor to describe an invisible barrier that keeps women from rising beyond a certain level in an enterprise’s hierarchy [15]. Moreover, the inequalities that women face in gaining access to work, career progression and rewards, along with the consequences of career breaks or part-time work due to caring responsibilities, labour market segregation, the parenthood penalty and stereotypes about the roles of men and women, are inevitably linked to the persistent gender pay gap.

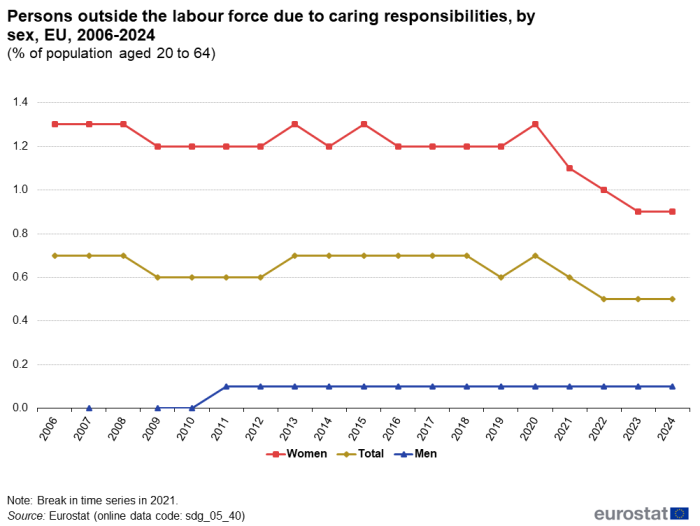

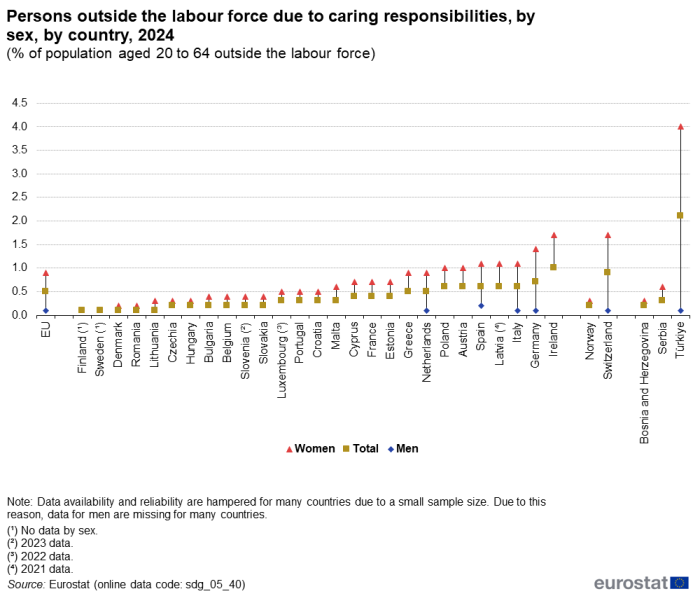

More women than men are outside the labour force due to caring responsibilities

Women still tend to take on a larger share of caring responsibilities for children and other family members. In 2024, 0.9% of women willing to work were outside the labour force due to caring responsibilities, which was nine times higher than the 0.1% rate for men. This resulted in a gender gap of 0.8 percentage points. Overall, 0.5% of the total population (aged 20 to 64) that wanted to work were outside the labour force due to caring responsibilities for adults with disability or children. This can be attributed to the lack of available, accessible and quality formal care services, especially for children.

Between 2018 and 2024, the share of the total population outside the labour force due to caring responsibilities fell from 0.7% to 0.5%. For women, this share fell by 0.3 percentage points, while for men it has stagnated at 0.1% over the past five years. As a result, the gender gap has narrowed by 0.3 percentage points since 2018.

Leadership positions

Traditional gender roles, a lack of support to allow women and men to balance care responsibilities with work, and political and corporate cultures are some of the reasons why women are underrepresented in decision-making processes. Promoting equality between women and men in this area is one of the EU’s priorities for achieving gender equality.

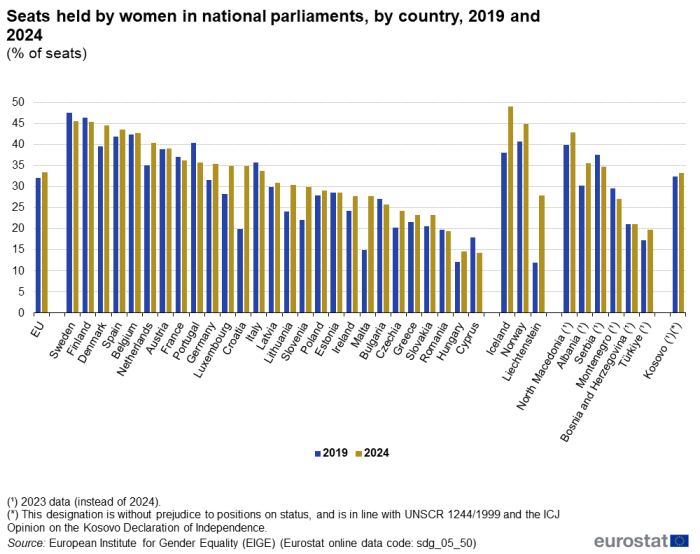

The increase in the share of seats held by women in national parliaments has slowed in recent years

The share of seats in national parliaments in the EU held by women has increased almost steadily since 2003, reaching 33.4% in 2024, which is the highest level recorded to date. However, the rate of increase over the past five years has slowed compared with previous years, with the share growing by only 1.3 percentage points since 2019. Differences between Member States vary greatly. In 2024, national parliaments (lower house and upper house, where relevant) in Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Spain, Belgium and the Netherlands all had at least 40% of each gender. At the other end of the spectrum, women accounted for less than a fifth of the members of national parliaments in Romania, Cyprus and Hungary. Between 2019 and 2024, this share declined in almost a third of Member States, including the two best performing countries (Sweden and Finland). In 2024, there was consequently no single EU country where women held the most seats. Looking outside the EU, Iceland almost achieved parity in 2024, with women occupying 49.2% of seats.

The share of female members of government (senior and junior ministers) in the EU was still lower than for men, at 35.1% in 2024, although this was a 12.5 percentage point increase from 22.6% in 2003. However, striking differences exist between Member States. Governments were gender-balanced (meaning at least 40% of each gender) in ten countries but remained predominantly male in five countries (Czechia, Croatia, Slovakia, Malta and Cyprus). Additionally, Hungary has had an all-male cabinet since 2023. The number of female heads of government in EU countries has also shown an increase, albeit at a low level. In 2024, the share of female heads of government stood at 14.8%. Four Member States had a female prime minister: Denmark, Italy, Latvia and Lithuania. Over the period from 2003 to 2024, the highest share of female heads of government was observed in 2022 and 2023 with 22.2%, meaning there were never more than six women holding this executive position at the same time [16]. Contributing to this under-representation is the fact that women seldom become leaders of major political parties, which are instrumental in selecting party leaders and selecting the candidates for election. Another factor is that gender norms and expectations reduce the pool of female candidates for selection as electoral representatives.

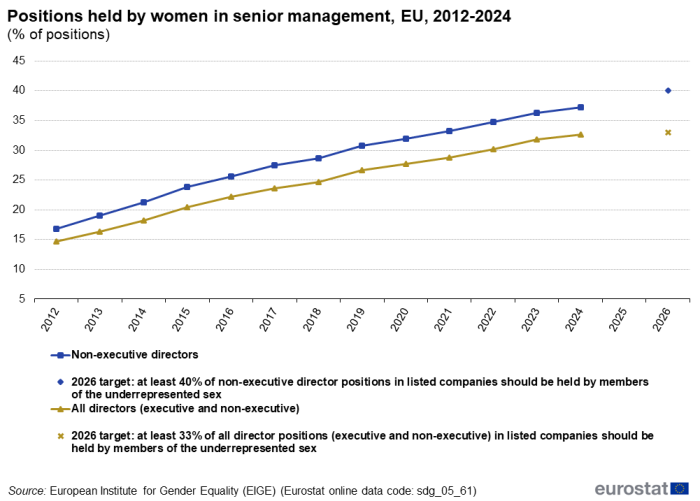

The shares of female directors of the largest listed companies have increased further and the EU is on track to meet its 2026 targets

Women held 32.6% of all director (executive and non-executive) positions and 37.2% of non-executive director positions in the largest listed companies in 2024. This level of representation was achieved after a steady 17.9 percentage point increase for all director positions and a 20.4 percentage point increase for non-executive director positions since 2012. Both shares indicate that the EU is on track to meet both of its targets for at least 33% of all director positions and 40% of non-executive director positions in listed companies to be held by members of the underrepresented sex by 2026. However, the numbers also mean most director positions in the largest listed companies are still held by men. In 2024, the share of all director positions (executive and non-executive) varied strongly across the EU, from 47.0% in France to 10.1% in Hungary. Eleven countries already exceeded the 33% target.

Main indicators

Gender-based violence against women

This indicator is based on the results of the 2021 EU survey on gender-based violence against women and other forms of inter-personal violence (EU-GBV). Gender-based violence against women is defined as ‘violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or violence that affects women disproportionately’ (Istanbul Convention, Article 3,d). This indicator covers physical (including threats) or sexual violence in adulthood.

Source: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), Eurostat (sdg_05_11)

Source: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), Eurostat (sdg_05_11)

Gender employment gap

The gender employment gap is defined as the difference between the employment rates of men and women aged 20 to 64. The employment rate is calculated by dividing the number of people aged 20 to 64 in employment by the total population of the same age group. The indicator is based on the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: Eurostat (sdg_05_30)

Gender pay gap in unadjusted form

The gender pay gap in unadjusted form represents the difference between average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees and of female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees. The indicator has been defined as unadjusted because it gives an overall picture of gender inequalities in terms of pay and measures a concept which is broader than the concept of equal pay for equal work. The gender pay gap is based on the methodology of the structure of earnings survey (SES), which is carried out every four years.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_05_20)

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_05_20)

Gender gap for being outside the labour force due to caring responsibilities

The population outside the labour force comprises individuals who are not employed and are either not actively seeking work or not available to work (even if they have found a job that will start in the future). Therefore, they are neither employed nor unemployed. This definition used in the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) is based on the resolutions of the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) organised by the International Labour Organization. The reason for being outside the labour force covered by this indicator includes ‘care of adults with disabilities or children’. Only people who express willingness to work, despite being outside the labour force, are considered.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_05_40)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_05_40)

Seats held by women in national parliaments

This indicator refers to the proportion of women in national parliaments in both chambers (lower house and upper house, where relevant). The data stem from the Gender Statistics Database of the European Institute for Gender Equality.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), Eurostat (sdg_05_50)

Source: European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), Eurostat (sdg_05_50)

Positions held by women in senior management

This indicator measures the share of female directors (executive and non-executive) and non-executive directors on formal boards in the largest publicly listed companies. The data presented in this section stem from the Gender Statistics Database of the European Institute for Gender Equality.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), Eurostat (sdg_05_61)

Source: European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), Eurostat (sdg_05_61)

Footnotes

- Please note that the data were collected between September 2020 and March 2024. As most of the data were collected during 2021, it is referred as wave 2021. ↑

- Source: Eurostat (gbv_any_du). ↑

- Source: Eurostat (gbv_any_lim). ↑

- Source: Eurostat (crim_hom_soff). ↑

- Source: Eurostat (crim_hom_vrel). ↑

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2022), Gender-related killings of women and girls (femicide/feminicide). ↑

- For more information see Eurostat metadata on Crime and criminal justice (crim). ↑

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014), Violence against women: an EU-wide survey, Main results, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 25-26, 32. ↑

- European Commission (2025), Joint Employment Report 2025, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ↑

- Source: Eurostat (tepsr_lm230). ↑

- Source: Eurostat (lfst_hheredty). ↑

- Source: Eurostat (lfsa_epgar). ↑

- Source: Eurostat (lfsi_pt_a). ↑

- European Commission (2025), Joint Employment Report 2025, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ↑

- Eurostat (2021), Gender pay gaps in the European Union - a statistical analysis. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ↑

- European Institute for Gender Equality, Gender Statistics Database (National governments: presidents and prime ministers). ↑

Explore further

Other articles

Database

Thematic section

Publications

Further reading on gender equality

- European Commission (2024), 2024 Report on gender equality in the EU, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Commission (2025), Joint Employment Report 2025, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Brussels.

- European Commission, Women’s situation in the labour market.

- European Institute for Gender Equality (2021), Gender inequalities in care and consequences for the labour market.

- Eurostat (2022), Gender pay gaps in the European Union — a statistical analysis — Revision 1, 2021 edition, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

- Encinas-Martín, M. and M. Cherian (2023), Gender, Education and Skills: The Persistence of Gender Gaps in Education and Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- UN Women (2022), Gender equality for health and well-being: Evaluative evidence of interlinkages with other SDGs.

- UN Women (2024), Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The gender snapshot 2024.

- World Economic Forum (2023), The Global Gender Gap Report 2023.

Methodology

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2025 edition’.

External links

Further data sources on gender equality