SDG 17 - Partnerships for the goals

Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development

Data extracted in April 2024.

Planned article update: June 2025.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’. This report is the eighth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 17 calls for a global partnership for sustainable development. It highlights the importance of macroeconomic stability and of mobilising financial resources for developing countries. It also stresses the importance of trade and equitable rules for governing it. The goal also emphasises the importance of access to science and technology, in particular internet-based information and communications technology.

Full article

Partnerships for the goals in the EU: overview and key trends

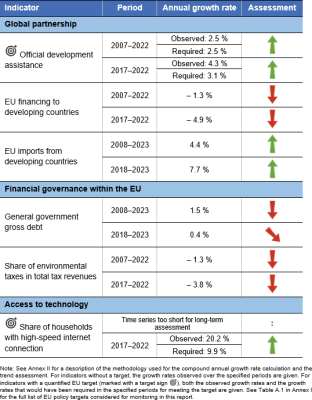

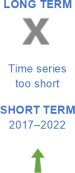

Partnership is at the essence of the EU and an overarching principle to approach the SDGs within and beyond the EU boundaries. Monitoring SDG 17 in an EU context focuses on global partnership, financial governance, and access to technology. Over the assessed five-year period, the EU’s progress in the area of global partnership was mixed. On the one hand, imports from developing countries have grown and the EU is currently on track towards its official development assistance (ODA) target, which is in part due to the support to Ukraine. On the other hand, despite the increase in ODA, overall EU financing to developing countries has declined. Additionally, financial governance within the EU remains a challenge, as exemplified by a falling share of environmental taxes in total tax revenues and high levels of general government gross debt. Meanwhile, access to technology in the EU progressed, with a significant increase in the share of households connected to high-speed internet.

Global partnership

To achieve the SDGs, partnerships are necessary between governments, the private sector, civil society and other parties. Wealthier economies such as the EU can support the implementation of the 2030 Agenda in developing countries through public and private, domestic and international resources. These resources can be both financial and non-financial [1]. This chapter focuses on the former. Overall, the global partnership indicators show a mixed picture for the EU over the past few years.

The EU supports country-led development through a range of financial support mechanisms

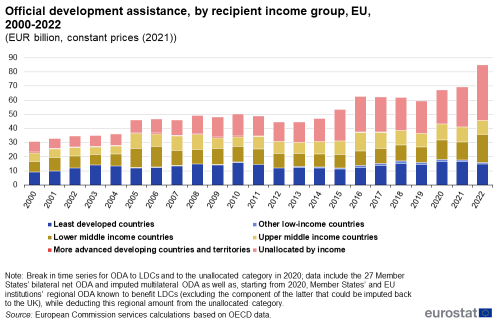

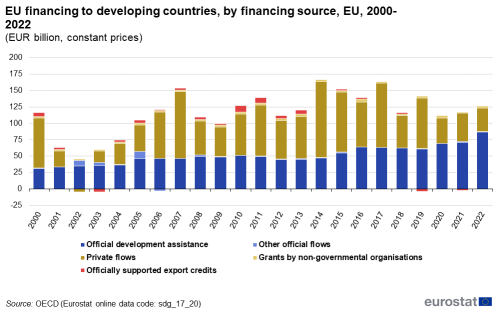

In 2015, in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, all countries recognised that international public finance plays an important role in complementing countries’ domestic efforts to mobilise public resources, especially in the poorest and most vulnerable countries. Official development assistance (ODA), other official flows (OOFs), private flows, such as foreign direct investment (FDI), grants by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and officially supported export credits [2] are some of the financial flows from the EU and its Member States to developing countries.

Regarding the total volume of financial flows from the EU to developing countries, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that total public and private EU financing to developing countries amounted to EUR 126.3 billion in 2022. When accounting for inflation, this is about the same level as the financial flows provided by the EU around 2010, but is — in part substantially — lower than the amounts provided between 2014 and 2019. While OOFs and grants by NGOs have remained rather marginal, ODA and private flows combined have accounted for at least 95 % of total EU financing for development since 2014. Overall, ODA has been the most reliable and steady financial flow from the EU to developing countries, while private flows have varied strongly over the years. The overall reduction in EU financing to developing countries over the past five-year period is a result of strong cuts in private flows of 64 %, while ODA has grown by 38 % since 2017.

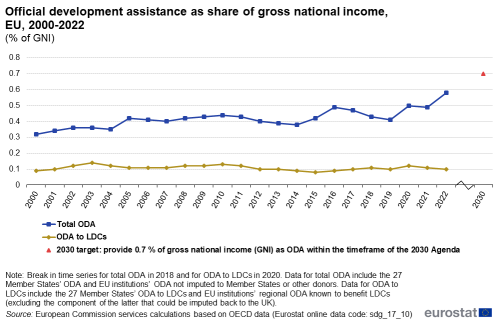

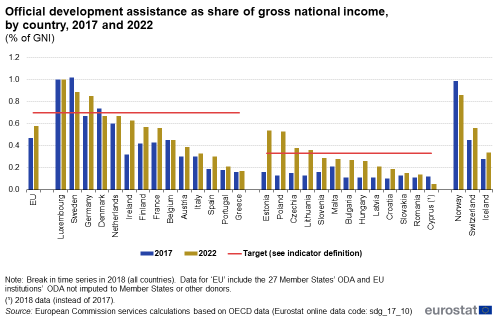

Official development assistance: a long struggle to meet targets

The idea that donor countries should contribute 0.7 % of their gross national income (GNI) to ODA has been on the international agenda for half a century. The EU is collectively committed to provide 0.7 % of GNI as ODA within the timeframe of the 2030 Agenda, as affirmed in the New European Consensus on Development. Member States that joined the EU after 2002 have committed to provide 0.33 % of their GNI for ODA. As a whole, the EU spent 0.58 % of its GNI on ODA in 2022, which is significantly higher than the 0.49 % provided in 2021. This increase notably includes but also goes beyond support to Ukraine. If the EU can maintain this increase over the next few years, the 2030 target is within reach. Nevertheless, only three EU countries — Luxembourg, Sweden and Germany — achieved the 0.7 % target in 2022, meaning additional efforts will be needed to meet the collective EU target by 2030.

The EU remains the world’s biggest ODA donor

In 2022, the EU maintained its position as the biggest ODA donor globally, providing about EUR 92.1 billion. This figure refers to the combined ODA provided by the 27 EU Member States and EU institutions. Moreover, with 0.58 % in 2022, the EU’s overall ODA/GNI ratio was significantly higher than for most other Development Assistance Committee’s (DAC) donors such as Canada, Japan or the United States.

The EU seeks to support least developed countries in particular

To direct resources where they are most needed — least developed countries (LDCs) and countries in states of fragility and conflict — the EU has a target to collectively provide 0.15–0.20 % of GNI to LDCs in the short term, reaching 0.20 % within the timeframe of the 2030 Agenda. In 2022, the EU’s collective official development assistance to LDCs accounted for 0.10 % of GNI, a slight decrease compared to previous years. The EU has thus not progressed towards its 0.20 % target over the past few years. In 2022, only two Member States – Luxembourg and Sweden – exceeded the targeted GNI ratio of ODA to LDCs.

ODA is only a part of several financing mechanisms

The EU seeks to ensure that developing countries can combine aid, investment and trade with domestic resources and policies to build capacity and become self-reliant. ODA, for example, can be used as a catalyst to mobilise other financial resources such as domestic tax revenues or resources from the private sector. Other innovative instruments have been developed, such as blending grants with loans, guarantees or equity from public and private financiers.

EU financial support, combined with domestic and private revenues, can provide a basis for achieving the 2030 Agenda’s goals, allowing for investment in social services, clean energy, infrastructure, transport and information and communications technologies. In the best case, developing countries could leapfrog some of the unsustainable modes of production and consumption that industrialised countries use.

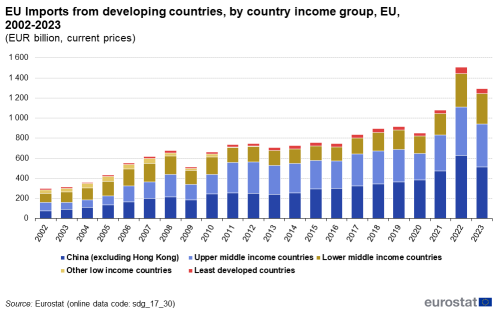

EU imports from developing countries have increased in recent years

Trade’s potential contribution to sustainable development has long been acknowledged. This is reflected in the EU's 2021 Trade Policy Review, along with the European Green Deal which stresses the contribution that trade policy can make to achieving the EU’s ambition on sustainable development.

Exports can create domestic jobs and allow developing countries to obtain foreign currency, which they can use to import necessary goods. Better integration of developing countries into world markets may reduce the need for external public flows. Several of the SDGs refer to the importance of trade for sustainable development. However, it needs to be noted that the EU’s trade-related indicators do not provide insights on whether the products in question are produced in an environmentally and socially sustainable manner.

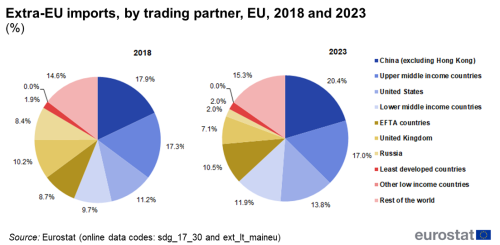

Between 2008 and 2023, EU imports from developing countries almost doubled from EUR 676 billion to EUR 1 292 billion, which corresponds to an increase of 4.4 % per year on average. Over the short term, since 2018, imports have grown even more strongly, by 7.7 % a year on average. The increase since 2018 was mainly driven by growth in imports from lower middle income countries and China, whose imports rose by around 62 % and 50 %, respectively.

Imports from developing countries to the EU as a share of imports from all countries outside the EU increased from 43.5 % in 2008 to 51.3 % in 2023. Similar to 2021 and 2022, developing countries (including China) thus accounted for slightly more than half of all extra-EU imports in 2023. China (excluding Hong Kong) alone accounted for 20.4 % of EU imports in 2023. This is remarkably higher than the share of imports from the United States, which accounted for 13.8 %. Conversely, the almost 50 countries classified as least developed by the UN accounted for just over 2 % of all EU imports in 2023 [3].

‘Aid for trade’ is a part of ODA that is targeted at trade-related projects and programmes. It aims to build trade capacity and infrastructure in developing countries, particularly least developed countries. The EU and its Member States were the leading global providers of aid for trade in 2020, providing EUR 23 billion, or 47 % of global aid for trade. Just three donors — the EU institutions as well as Germany and France — provided 90 % of this overall sum. The share of aid for trade to LDCs was 13 % of overall aid for trade in 2020, two percentage points lower than in the three years before [4].

Financial governance within the EU

To help other countries to advance their economies, the EU’s own economies must also remain on a sustainable development path. Macroeconomic stability in the EU is therefore one pillar of the Union’s contribution to implementing the SDGs. In addition, the EU seeks to make its economy greener. In a global context, where consumption patterns in one region can severely impact production patterns elsewhere, it is particularly important that prices reflect the real costs of consumption and production. They should include payments for negative externalities caused by polluting activities or other activities that damage human health and the environment. Moreover, the EU has pointed out that environmental taxes may offer opportunities to reduced taxes in other areas, for example on labour.

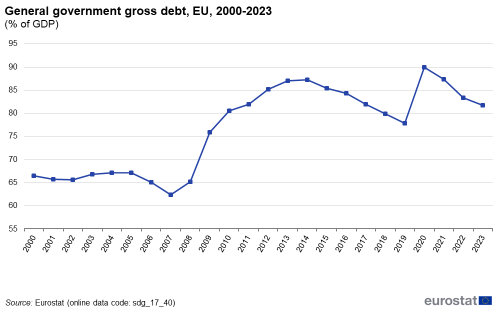

The EU’s government debt-to-GDP ratio has started falling again after its COVID-19-related peak

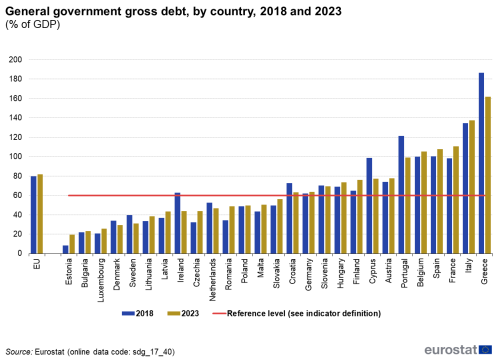

According to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, government debt should not exceed 60 % of GDP in EU Member States. As a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis and related public spending, the EU’s overall debt-to-GDP ratio rose sharply in 2020 to reach 90.0 %, which is a 12.2 percentage point increase compared with 2019. Since then, however, the EU’s debt-to-GDP ratio has fallen again, reaching 81.7 % in 2023. While this is 8.3 percentage points lower than the 2020 peak, it is still 1.8 percentage points higher than the 2018 value of 79.9 %.

In 2023, Member States’ debt-to-GDP ratios ranged from 19.6 % in Estonia to 161.9 % in Greece. Thirteen EU countries exceeded the 60 % threshold in 2023 and five Member States had debt-to-GDP ratios above 100 %. Between 2018 and 2023, the strongest reductions in debt-to-GDP ratios were reported by Greece (- 24.5 percentage points), Portugal (- 22.4 percentage points) and Cyprus (- 21.2 percentage points). In contrast, the ratios rose strongest in Romania (+ 14.4 percentage points), France (+ 12.4 percentage points) and Czechia (+ 11.9 percentage points).

‘Greening’ the taxation system remains a challenge

Environmental taxes help to provide the right price signals and incentives to producers, users and consumers to encourage less polluting consumption and to contribute to sustainable growth. They may also provide opportunities to reduce taxes in other areas, for example on labour, and if revenue for adequate social protection is protected, they can offer a win-win option for addressing both environmental and employment issues, as laid out in the EU’s Action Plan for Fair and Simple Taxation. Environmental taxes support the transition to a climate-neutral economy [5]. As indicated in the Communication on Business taxation for the 21st century as regards the EU tax mix, behavioural taxes, such as environmental and health taxes, continue to be of growing importance for EU tax policies. Well-designed environmental taxes help to support the green transition by sending the right price signals, as well as implementing the polluter pays principle. They also generate revenue that could compensate some of the needed labour tax cuts.

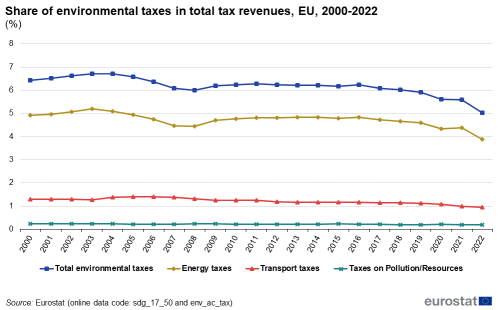

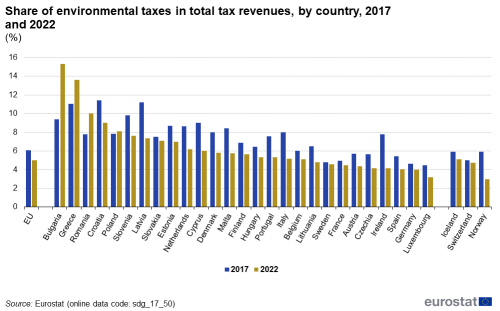

In 2022, environmental taxes accounted for only 5.0 % of total tax revenues in the EU, which is a new record low in the time series since 2000. In comparison, labour taxes accounted for 50.6 % in 2022 [6]. Energy taxes constituted the main part of environmental taxes, accounting for 3.9 % of tax revenues in 2022, followed by transport taxes with a share of 0.9 %. In comparison, taxes on pollution and resources – the third component of environmental taxes – remained negligible, accounting for only 0.2 % of total tax revenues in 2022 [7]. The share of total environmental taxes has fallen considerably since 2017, when they accounted for 6.1 % of tax revenues. Across Member States, the share of environmental taxes in total tax revenues ranged from 3.2 % in Luxembourg to 15.3 % in Bulgaria in 2022. Compared with 2017, their share has decreased in almost all EU countries. Only four countries — Bulgaria, Greece, Romania and Poland — reported increases in the share of environmental taxes over this period.

The ratio of labour to environmental taxes shows how much higher a country’s share of labour tax revenues is than its share of environmental taxes. In 2022, this ratio ranged from 2.2 in Bulgaria to 15.1 in Luxembourg. It has increased in most Member States since 2017, indicating a relative shift in taxation from environment to labour across the EU [8].

EU Member States spend around 2 % of their GDP to protect the natural environment

The decline in the prioritisation of environmental taxation is partly reflected in national environmental expenditures. National expenditure on environmental protection measures the amount of resources a country uses to protect the natural environment. It includes current expenditure on environmental protection activities, investments in these activities and net transfers to other parts of the world. At EU level, environmental protection expenditure amounted to EUR 342 billion in 2022, which corresponds to 2.2 % of GDP. Across the Member States, expenditure ranged from 3.6 % of GDP in Austria to 0.9 % in Ireland and Luxembourg in 2021 [9].

Access to technology

In today’s economies and societies, digital connections are crucial. Instant communication between individuals, bank transfers, office work, public dissemination of information and data analysis are only some of the activities that depend on the internet. Regions without fast internet connections have serious social and economic disadvantages in a digitalised world. As a result, making Europe fit for the digital age is one of the Commission’s six priorities for 2019 to 2024. The aim is to make the digital transformation work for people and businesses while helping to achieve the target of a climate-neutral Europe by 2050.

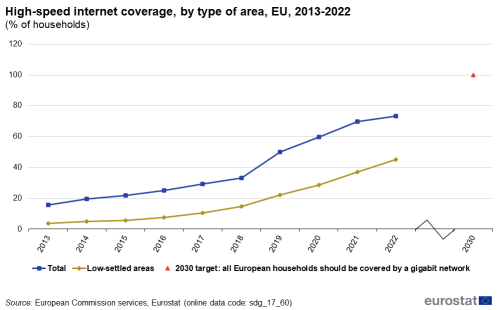

Considerable progress has been made in rolling out high-speed internet coverage across the EU

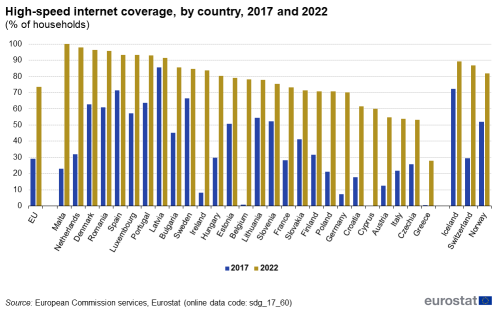

The uptake of high-speed internet coverage — referring to fibre connections or other networks offering similar bandwidth — has improved considerably over the past few years across the EU. While only 29.2 % of EU households enjoyed such connectivity in 2017, this share has risen considerably, reaching 73.4 % in 2022. If high-speed internet roll-out continues at this pace, the EU will reach 100 % coverage well ahead of 2030. Connectivity has also improved in rural areas [10]. Between 2017 and 2022, the share of rural households with a fixed high-speed internet connection increased from 10.6 % to 45.1 % across the EU.

At Member State level, Malta had already achieved a 100 % fixed high-speed internet connectivity for all households in 2019. In 2022, it was followed by the Netherlands (97.8 %), Denmark (96.3 %) and Romania (95.6 %). In contrast, fixed high-speed internet connections were the least widespread in Greece, with only 27.8 % of households enjoying such connectivity. All remaining Member States had connection to high-speed internet rates above 50 % in 2022.

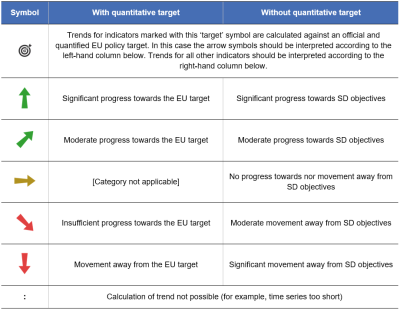

Main indicators

Official development assistance

Official development assistance (ODA) is provided by governments and their executive agencies to support economic development and welfare in developing countries. ODA must be concessional in character, having a grant element that varies in proportion depending on the recipient. Eligible countries are included in the Organisation for Economic Development and Cooperation’s (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) official list of ODA recipients. ODA disbursements and their purpose are reported by donors to the OECD. A new methodology to calculate the ODA value of concessional loans is applied from 2018 data onwards and affects the comparability of data with previous years. Additionally, a new methodology for calculating total ODA to LDCs is applied from 2020 data onwards, by including regional ODA known to benefit LDCs (on top of the bilateral net ODA to LDCs and imputed multilateral ODA to LDCs). Member States undertake to achieve the target to provide 0.7 % of their gross national income (GNI) towards ODA, while those which have achieved that target commit to remaining above it; Member States which joined the EU after 2002 will strive to increase their ODA/GNI spend to 0.33 %.

Source: European Commission services calculations based on OECD data (Eurostat (sdg_17_10))

Source: European Commission services calculations based on OECD data (Eurostat (sdg_17_10))

Source: European Commission services calculations based on OECD data.

EU financing to developing countries

EU financing to developing countries takes a number of forms. These, as documented by the OECD, include: official development assistance (ODA) (public grants or concessional loans with the aim of supporting economic development and welfare); other official flows (OOFs) (public flows that are not focused on development or with a grant element of less than 25 %); private flows (direct investment, bonds, export credits and multilateral flows); grants by non-governmental organisations (from funds raised for development assistance and disaster relief); and officially supported export credits. Data stem from the OECD (DAC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: OECD, Eurostat (sdg_17_20)

EU imports from developing countries

This indicator is defined as the value (at current prices) of EU imports from the countries on the DAC list of ODA beneficiaries. It indicates to what extent products from these countries access the EU market. Information for this indicator is provided by enterprises with a trade volume above a set threshold and is collected on the basis of customs declarations. This information is then adjusted by Member States to account for the impact of trade under this threshold.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_17_30)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_17_30) and (ext_lt_maineu)

General government gross debt

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) defines this indicator as the ratio of general government gross debt at the end of the year to gross domestic product at current market prices. For this calculation, general government gross debt is defined as the total consolidated gross debt at nominal (face) value in the following categories of government liabilities, as defined in ESA 2010: currency and deposits, debt securities and loans. The general government sector comprises central government, state government, local government and social security funds. The TFEU states that a Member State’s government debt-to-GDP ratio should be limited to 60 %.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_17_40)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_17_40)

Environmental taxes are defined as taxes based on a physical unit (or proxy of it) of something that has a proven, specific negative impact on the environment. There are four types of environmental taxes: energy taxes, transport taxes, and pollution taxes and resource taxes.

Source: Eurostat (online data codes: (sdg_17_50) and (env_ac_tax))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_17_50)

This indicator measures the share of households with fixed very high capacity network (VHCN) connection. Very high capacity network means either an electronic communications network that consists entirely of optical fibre elements at least up to the distribution point at the serving location, or an electronic communications network capable of delivering, under usual peak-time conditions, similar network performance in terms of available downlink and uplink bandwidth, resilience, error-related parameters, and latency and its variation. The data are collected for the Broadband Coverage in Europe studies published by the European Commission. Data until 2018 refer to fibre to the premises (FTTP) only, while data from 2019 onwards refer to both FTTP and Data Over Cable Service Interface Specification (DOCSIS) 3.1. DOCSIS allows adding high-bandwidth data transfer to existing cable television systems.

Source: European Commission services, Eurostat (sdg_17_60)

Source: European Commission services, Eurostat (sdg_17_60)

Direct access to

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’.

Further reading on partnership for the goals

- European Commission (2021), Trade Policy Review -An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy, COM (2021) 66 final.

- European Commission (2023), 2023 annual report on the implementation of the European Union’s external action instruments in 2022, Luxembourg.

- European Commission (2024), EU Aid for Trade Progress Report 2023, Brussels.

- European Commission (2022), Investing in sustainable development : progress report 2018-2020, Publications Office of the European Union, Brussels.

- European Union (2017), The new European Consensus on Development ‘Our World, Our Dignity, Our Future’, Joint statement by the Council and the representatives of the governments of the Member States meeting within the Council, the European Parliament and the Commission, 2017/C 210/01, Official Journal of the European Union, Volume 60.

- Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (2016), Nairobi Outcome Document: Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-Operation.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness (2011), Busan Partnership Agreement, Busan.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2023), Development Co-operation Report 2023: Debating the Aid System, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2015), Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development (Addis Ababa Action Agenda), UNGA Resolution 69/313 of 27 July 2015.

- United Nations, Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development (2024), Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2024, United Nations, New York.

Further data sources on partnership for the goals

Notes

- ↑ Non-financial resources include domestic policy frameworks, effective institutions and support for good governance, democracy, rule of law, human rights, transparency and accountability; see also the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA).

- ↑ The OECD defines export credits as loans for the purpose of trade and which are not represented by a negotiable instrument. They may be extended by the official or the private sector. If extended by the private sector, they may be supported by official guarantees; see http://www.oecd.org/dac/dac-glossary.htm#Export_Credits.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ext_lt_maineu)).

- ↑ European Commission (2023), EU Aid for Trade Progress Report 2022.

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2023), The role of (environmental) taxation in supporting sustainability transitions, Briefing.

- ↑ Taxes on labour are generally defined as all personal income taxes, payroll taxes and social contributions of employees and employers that are levied on labour income (both employed and non-employed). Data on labour taxes stem from the DG Taxation and Customs Union (‘Data on Taxation’ webpage).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (env_ac_tax)).

- ↑ Source: calculations based on data from DG Taxation and Customs Union (‘Data on Taxation’ webpage) and Eurostat (online data code: (env_ac_tax)).

- ↑ Eurostat (ten00135)

- ↑ In the context of the EU’s digital agenda scoreboard indicators, rural areas are defined as those with less than 100 people per square kilometre.