Labour market statistics at regional level

Data extracted in April 2024.

Planned article update: September 2025.

Highlights

In 2023, there were only 3 regions in the EU that reported a higher employment rate among women aged 20–64 than among men of the same age. All of them were located in Finland: Åland, Etelä-Suomi and Pohjois- ja Itä-Suomi.

In 2023, the highest regional unemployment rates in Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Austria, Portugal and Finland were recorded in their capital regions. The unemployment rate in the Austrian capital region of Wien was almost twice as high as that in any other Austrian region.

On 4 March 2021, the European Commission set out its ambition for a stronger, social EU to focus on jobs and skills, paving the way for a fair, inclusive and resilient socioeconomic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan (COM(2021) 102 final) outlines a set of specific actions and headline targets for employment, skills and social protection across the EU.

The European Year of Skills 2023/24 was designed to ‘promote reskilling and upskilling, helping people to get the right skills for quality jobs’. A principal aim of the European year was to provide fresh impetus to help the EU reach 2 targets that form part of the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, namely – by 2030 – to have

- at least 60% of adults in training over the course of a year

- an employment rate for people aged 20–64 of at least 78%.

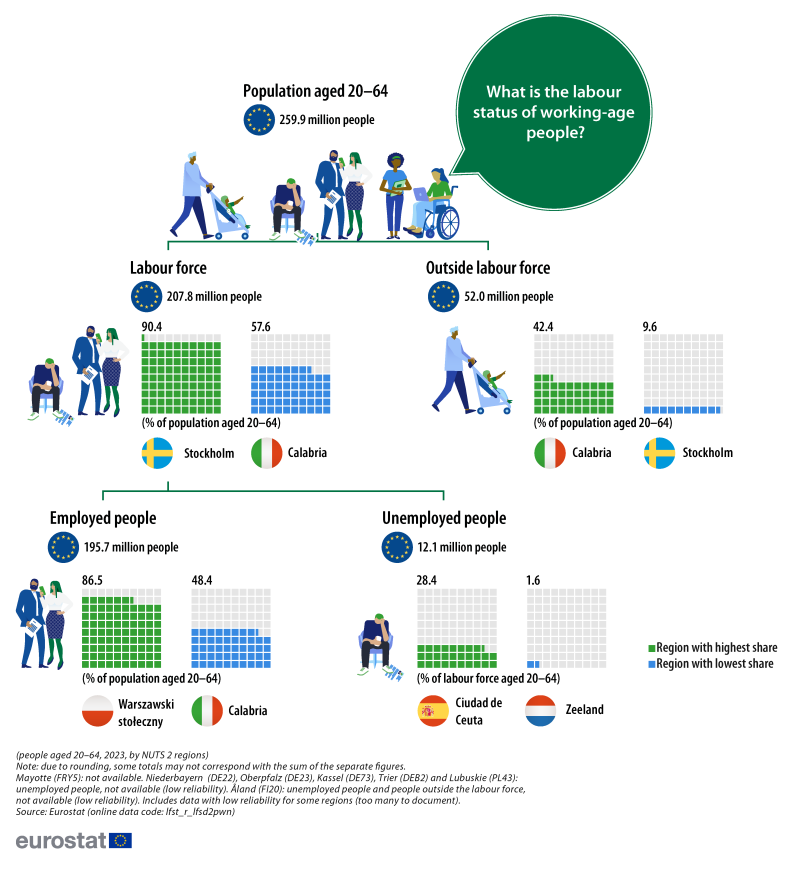

In 2023, the core working-age population of the EU (defined here as people aged 20–64) numbered 259.9 million, of which 52.0 million people were outside the labour force (in other words, economically inactive); this latter group is composed, among others, of students, pensioners, people caring for other family members, as well as volunteers and people unable to work because of long-term sickness or disability.

The EU’s labour force of core working age in 2023 was composed of 195.7 million employed people, in contrast to 12.1 million unemployed people who weren’t working but were actively seeking and available for work. The highest regional employment rate among NUTS level 2 regions was recorded in the Polish capital region of Warszawski stołeczny (86.5%), while the lowest rate was observed in the southern Italian region of Calabria (48.4%). The infographic above provides more details on the composition of the EU’s labour force, as well as other regional highlights.

Full article

Employment

More about the data: employment rate targets in the European Pillar of Social Rights

The employment rate is the percentage of employed people (of a given age) relative to the total population (of the same age).

Increasing the number and share of people in work is a principal policy objective for the EU. This goal formed part of the European employment strategy (EES) from its outset in 1997 and was subsequently incorporated into the Lisbon and Europe 2020 strategies. Subsequently, the employment rate was included as an indicator in the social scoreboard which is used to monitor the implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights. The EU’s employment rate target is to have, by 2030, at least 78% of the population aged 20–64 in work. The choice of this age range reflects the growing proportion of young people who remain within education into their late teens (and beyond), potentially restricting their participation in the labour market. At the other end of the age spectrum, the vast majority of people in the EU are retired after the age of 64.

Individual EU countries have been set different employment rate targets. For those countries with relatively high employment rates, national targets are generally higher than the overall EU target, for example, the target in Hungary has been set at 85.0%, in Germany at 83.0% and in the Netherlands at 82.5%.

The EU employment rate was 75.3% in 2023

Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, the EU’s employment rate for the core working-age population (20–64 years) had increased for 6 consecutive years, reaching 73.1% by 2019. This pattern came to an abrupt end in 2020 as the rate fell 0.9 percentage points. However, almost all of the losses during the initial stages of the pandemic were recovered in 2021. The EU’s employment rate continued to increase in 2022 and 2023, rising 1.6 and 0.7 points, respectively, to stand at an historical high of 75.3% in 2023.

Map 1 shows the employment rate in 2023 for NUTS level 2 regions: those regions with rates already equal to or above the EU target of 78.0% are shown in shades of teal. In 2023, approximately 45% of EU regions (109 out of the 241 for which data are available) had already reached or surpassed this level. These regions were mainly concentrated in Czechia (all 8 regions), Denmark (all 5 regions), Germany (35 out of 38 regions; the exceptions being Berlin, Düsseldorf and Bremen), Hungary (6 out of 8 regions), the Netherlands (all 12 regions), Slovakia (3 out of 4 regions) and Sweden (all 8 regions); the group included Estonia, Cyprus and Malta too.

In 2023, the Polish capital region of Warszawski stołeczny had the highest employment rate among NUTS level 2 regions of the EU, at 86.5%. The 2nd highest rate was also recorded in a capital region, Bratislavský kraj in Slovakia (85.8%). The 3rd highest rate was observed in the western German region of Trier (85.4%), where a relatively high proportion of people commute across a national border to work in Luxembourg. Several other capital regions boasted relatively high employment rates, including: Stockholm in Sweden (85.2%), Praha in Czechia (84.8%), Budapest in Hungary (84.4%), Noord-Holland in the Netherlands (84.0%) and Sostinės regionas in Lithuania (83.2%).

Many of the regions with relatively low employment rates were characterised as rural, sparsely-populated, or peripheral regions. This pattern was particularly apparent in southern regions of Spain and Italy, much of Greece, some regions in Romania, and the outermost regions of France. These areas typically suffered from limited employment opportunities, especially for individuals with intermediate and high skill levels.

Another group of regions characterised by relatively low employment rates are former industrial heartlands that haven’t adapted economically. Some of these have witnessed the negative impact of globalisation on traditional sectors of their economies (such as coal mining, steel or textiles manufacturing). Examples include a band of regions running from north-east France into the Région wallonne (Belgium).

Approximately a quarter (65 out of the 241 regions for which data are available) of all EU regions had an employment rate that was below 72.5% in 2023 (as shown by the 2 darkest shades of gold in Map 1). This group included the capital regions of Belgium, Italy, Greece and Austria, with rates of 66.5%, 68.1%, 69.0% and 70.8%, respectively. This group also included 3 regions in southern Italy where less than half of the core working-age population was employed: Calabria (48.4%), Campania (48.4%) and Sicilia (48.7%).

Map 1: Employment rate, 2023

(%, people aged 20–64, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat

(lfst_r_lfe2emprtn)

In 2023, the highest regional disparities for employment rates were observed in Italy

In 2023, all of the multi-regional eastern and Baltic countries, as well as Denmark, Ireland, Spain and Sweden reported that their highest employment rate was in their capital region. By contrast, in Belgium, Germany and Austria the situation was more or less the opposite, as their capital regions recorded some of the lowest employment rates.

Several EU countries face considerable labour market disparities across regions, with labour shortages in some regions contrasted against persistently high unemployment in others. A population-weighted coefficient of variation provides a means to analyse these intra-regional disparities. Figure 1 shows that Italy had the highest regional disparities in 2023, with a coefficient of variation of 16.3%. Broadly, there was a north-south split: the Alpine region of Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano/Bozen recorded the highest employment rate (79.6%), while the southern regions of Calabria and Campania had the lowest rates (both 48.4%).

Belgium (8.5%), Romania (7.7%) and Spain (6.9%) had the next highest coefficients of variation for regional employment rates in 2023

- in Belgium, some of the highest regional employment rates were recorded across the regions of Vlaams Gewest, while lower rates were observed in the capital Région de Bruxelles-Capitale / Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest and across the regions of Région wallonne

- in Romania, by far the highest regional employment rate was recorded in the capital region of Bucureşti-Ilfov, while notably lower rates were observed in 2 southern regions

- in Spain, the highest regional employment rates were recorded in northern and eastern regions as well as the capital city region in the centre; while most lower rates were observed in peripheral, southern and western regions.

At the other end of the range, the lowest regional disparities for employment rates – with a coefficient of variation of 2.0% or less – were recorded in Portugal, Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands.

Figure 1 also shows some convergence in regional employment rates across the EU. Between 2013 and 2023, the coefficient of variation fell from 13.4% to 10.0%. In 15 (out of 17) EU countries for which data are available, there was a decrease in intra-regional disparities for employment rates. The biggest falls – in relative terms – were observed in Finland, Portugal, Czechia and Greece, where regional disparities fell by more than 40.0%. By contrast, the largest increase was recorded in Romania, as regional disparities increased by 18.5%.

(coefficient of variation in %, people aged 20–64, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_lmder)

The EU’s gender employment gap was 10.2 percentage points in 2023

In 2023, the EU’s gender employment gap was 10.2 percentage points: this gap is defined as the difference between the employment rates of men and women aged 20-64. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan set a subgoal of halving the EU’s gender employment gap, as part of its overall target to increase the employment rate to 78% by 2030. The subgoal foresees reducing the gender employment gap to 5.6 percentage points by 2030, equivalent to an average fall of 0.5 points each year (over the period 2019–30).

Long-standing challenges linked to female participation in the labour force are illustrated by persistent gender gaps for employment and pay. These gaps between the sexes exist for a variety of reasons, among which

- women often bear a disproportionate share of unpaid care and household chores that may limit their availability for paid employment

- gender bias and discrimination when hiring, promoting and paying women

- fewer women in leadership positions to draw attention to gender-related policies or mentor more junior female staff

- a lack of affordable childcare and support for working parents

- disincentives in tax and benefit system that can lead to 2nd earners bearing a higher tax burden when they choose to participate in the labour market

- occupational segregation, with women often concentrated in specific activities that are characterised by lower wages and/or fewer opportunities for career development.

The gender employment gap is also included in the EU’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) indicator set. Goal 5 seeks to achieve gender equality by, among other actions, ending all forms of discrimination, violence, and any harmful practices against women and girls, while promoting women’s social and economic empowerment.

In Finland, there were 3 regions where a higher proportion of women (aged 20–64) than men (of the same age) were employed in 2023

In 2023, 52 out of 241 NUTS level 2 regions for which data are available reported a gender employment gap that was already 5.6 percentage points or lower; they are shown in different shades of gold in Map 2. This group of 52 regions was mainly concentrated in France (13 regions), Germany (7 regions), Sweden (7 out of 8 regions) and Finland (all 5 regions). Those regions with relatively small gender employment gaps were often characterised by high overall employment rates.

In 2023, there were only 3 regions within the EU that reported a higher employment rate for women (than for men): Åland, Etelä-Suomi and Pohjois- ja Itä-Suomi (all in Finland). In the Slovak capital region of Bratislavský kraj, there was no difference in employment rates between the sexes.

Despite some progress, female employment rates still lag behind male rates in the vast majority of EU regions. The European Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy 2020–25 is designed, among other goals, to counter gender stereotypes and promote women’s participation in decision-making, while closing gender gaps in the labour market.

EU regions with relatively large gender employment gaps were often characterised by higher unemployment rates and levels of women outside the labour force. In 2023, there were 24 NUTS level 2 regions that had gaps of at least 17.5 percentage points (as shown by the darkest shade of teal in Map 3). This group was concentrated in Greece (11 out of 13 regions), central/southern Italy (8 regions) and Romania (4 regions); the other region was Střední Čechy in Czechia. The Italian regions of Campania and Puglia (both 29.5 points) and the Greek region of Sterea Elláda (29.3 points) had the highest gender employment gaps in the EU.

Map 2: Gender employment gap, 2023

(percentage points, people aged 20–64, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat

(lfst_r_lfe2emprtn)

Employment – focus on qualifications and skills

More about the data: young people who are neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET)

The share of young people (aged 15–29) who are neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET) provides a useful measure for studying the vulnerability of young people in terms of their labour market participation and social exclusion.

The NEET rate is expressed relative to the total population of the same age (15–29); the numerator includes not only young people who are unemployed but also young people who are outside the labour force for reasons other than education or training (for example, because they are caring for family members, volunteering or travelling, or unable to work for health reasons).

Within the European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, the EU set a policy target whereby the NEET rate should decrease to less than 9% by 2030. Having peaked at 16.1% in 2013, the rate subsequently fell during 6 consecutive years. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it climbed to 13.8% in 2020, after which a downward trend returned. In 2023, the EU’s NEET rate stood at 11.2%.

Economic crises tend to hit young people disproportionately, as young people are more likely to work with temporary and other forms of atypical contracts that are easier to terminate. The NEET rate can be used to investigate the share of young people who haven’t transitioned from education/training to employment. It is generally considered a more comprehensive measure than the unemployment rate, insofar as it is more closely linked to young people’s risk of social and labour exclusion.

In 15 out of the 237 NUTS level 2 regions for which data are available, at least 20.0% of all young people aged 15–29 were neither in employment, nor in education or training in 2023 (these regions are shaded in the darkest shade of teal in Map 3). Some of the highest NEET rates were recorded in predominantly rural regions located in southern and eastern EU countries, as well as the outermost regions of France. More narrowly, there were 7 regions where more than 25.0% of all young people were neither in employment, nor in education or training

- 3 of these were located in Italy – Campania (26.9%), Calabria (27.2%) and Sicilia (27.9%)

- 3 were located in Romania – Centru (25.5%), Sud-Est (26.8%) and Sud-Vest Oltenia (27.7%)

- however, the highest NEET rate was recorded in the French outermost region of Guyane, where 29.7% of all young people were neither in employment, nor in education or training.

In 2023, there were 84 NUTS level 2 regions that reported a NEET rate that was already below the EU’s policy target of 9.0% (to be reached by 2030); they are shown in golden shades within Map 3. This group of 84 regions was concentrated in Ireland (all 3 regions), the Netherlands (all 12 regions), Austria (7 out of 9 regions), Slovenia (both regions), Slovakia (3 out of 4 regions) and Sweden (all 8 regions); it included Luxembourg and Malta too. There were 9 regions within the EU where the NEET rate was less than 5.0% in 2023 (as shown by the darkest shade of gold). A majority of these were located in the Netherlands. They were joined by 2 regions from Sweden and the capital regions of Hungary and Poland. The lowest NEET rates were recorded in Småland med öarna in Sweden (3.7%) and Overijssel in the Netherlands (3.9%).

Capital regions generally recorded lower than (national) average shares of young people who were neither in employment nor in education or training. In 2023, the only exceptions – among multi-regional EU countries – were in Austria, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands; the difference in the latter was minimal.

Map 3: Share of young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET), 2023

(%, people aged 15–29, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat

(edat_lfse_22)

In 2023, the EU’s NEET rate was 2.4 percentage points higher among young females than young males

Figure 2 confirms that among NUTS level 2 regions in 2023, the NEET rate ranged from a high of 29.7% in the French outermost region of Guyane down to a low of 3.7% in the south-eastern Swedish region of Småland med öarna. It also shows that some but not all regions characterised by high NEET rates displayed considerable gender differences, with NEET rates generally higher for females (than males). The right-hand chart doesn’t necessarily show the largest gender gaps, rather it presents gender gaps for those regions with the highest/lowest regional shares.

In the EU, the share of young females aged 15–29 who were neither in employment nor in education and training was 12.5% in 2023. This figure was 2.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding figure for young males, which stood at 10.1%. Across NUTS level 2 regions, it was more common to find higher NEET rates for young females (than for young males). This gender gap was most pronounced in regions located in eastern EU countries and Greece, where cultural, economic and societal factors may play a role in acting as barriers for young females to enter the workforce. The highest NEET rates among young females were recorded in the Romanian regions of Sud-Est (34.5%) and Sud-Vest Oltenia (34.4%), and the southern Italian region of Sicilia (30.4%). For young males, the highest NEET rates were observed in the French outermost region of Guyane (29.7%), Severozapaden in Bulgaria (28.5%) and Calabria in southern Italy (27.3%).

(%, people aged 15–29, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_22)

More about the data: employment rates by educational attainment

An individual’s level of educational attainment plays a key role when seeking employment. People with a tertiary level of educational attainment (as defined by the international standard classification of education (ISCED 2011 levels 5–8)) generally enjoy the most success when trying to find work. They also tend to be better shielded from the risks of unemployment than their peers with lower levels of attainment.

The data presented in this section are for the age group 25–64 as this represents a cohort of individuals who have generally completed their education or training and are most likely to be actively participating in the labour market. As such, it excludes younger individuals who may still be studying, as well as older individuals who may be in retirement.

In 2023, there were 182.9 million people aged 25–64 employed in the EU. The highest share of this cohort was composed of people with an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED levels 3–4; 44.9%), followed by people with a tertiary education (ISCED levels 5–8; 39.7%), while a relatively small share had no more than a lower secondary education (ISCED levels 0–2; 15.3%). The strong links between educational attainment and employment opportunities are demonstrated by the employment rates

- 58.7% for people with no more than a lower secondary education (hereafter referred to as a low level of education)

- 77.8% for people with an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (a medium level of education)

- 87.6% for people with a tertiary level of education (a high level of education).

Map 4 shows employment rates for people aged 25–64 according to these 3 different levels of educational attainment. In 2023, there were 46 NUTS level 2 regions that recorded employment rates for people with a low level of education that were below 50.0%. By contrast, employment rates for people with a medium or a high level of education exceeded 50.0% in every region of the EU. At the other end of the spectrum, there were 72 regions that recorded employment rates for people with a high level of education that were equal to or above 90.0%. By contrast, employment rates for people with a medium or a low level of education were consistently below 90.0% in every region of the EU.

In 2023, Východné Slovensko in Slovakia had the lowest employment rate for people with a low level of education …

The 1st part of Map 4 details employment rates for people aged 25–64 with a low level of education. In 2023, there were 46 NUTS level 2 regions with employment rates below 50.0%. They were mainly concentrated in eastern EU countries (other than Hungary and Slovenia), Belgium, France and southern Italy; this group also included the Greek and Austrian capital regions of Attiki and Wien, as well as the 2 autonomous regions of Ciudad de Ceuta and Ciudad de Melilla in Spain. In the easternmost region of Slovakia, Východné Slovensko, 25.3% of all people with a low level of education were employed. There were 3 other regions that reported no more than 1 in 3 people with a low level of education in employment: Severozapaden in Bulgaria (31.1%), Stredné Slovensko in Slovakia (31.8%) and Małopolskie in Poland (33.3%).

… while the highest employment rate for people with a medium level of education were recorded in the Czech region of Praha and the Portuguese Região Autónoma dos Açores

The 2nd map shows employment rates for people aged 25–64 with a medium level of education. In 2023, there were 29 NUTS level 2 regions where the employment rate for this cohort was equal to or above 85.0%. These regions were principally located in southern Germany, Czechia, western Hungary, the Netherlands and Portugal. The highest employment rates were recorded in the Czech capital region of Praha and the Portuguese island Região Autónoma dos Açores (both 87.8%), while rates of more than 87.0% were also observed in the Hungarian regions of Közép-Dunántúl and Nyugat-Dunántúl.

In 2023, employment rates for people with a high level of education were highest in the Polish capital region of Warszawski stołeczny and in the Nord-Est region of Romania

The 3rd map shows employment rates for people aged 25–64 with a high level of education. In 2023, there were 72 NUTS level 2 regions across the EU where the employment rate for this cohort was at least 90.0% (as shown by the darkest shade of blue). Approximately half of this group was concentrated in eastern EU countries: Poland (12 regions), Hungary (7 out of 8 regions), Romania (6 out of 8 regions), Slovakia (3 out of 4 regions), Slovenia (both regions), Croatia, Bulgaria (both 2 regions) and Czechia (a single region). This group of 72 also included 10 regions from Germany, 6 regions from each of Portugal and Sweden, 5 regions from the Netherlands, as well as 4 regions from Belgium, alongside single regions from France, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Austria and Finland. The highest employment rates for people with a high level of education were recorded in the Polish capital region of Warszawski stołeczny and in the Nord-Est region of Romania (both 93.7%).

In 2023, employment rates for people aged 25–64 with a high level of education were generally higher in capital regions than national averages. Indeed, capital regions often act as a magnet for highly qualified people, exerting considerable ‘pull effects’ through the varied educational, employment and social/lifestyle opportunities that they offer. This was particularly the case in Greece, as the employment rate for people with a high level of education was 3.2 percentage points higher than the national average in the capital region of Attiki; this pattern was also notable in Spain, Bulgaria, Croatia, Poland and Czechia. By contrast, the opposite pattern was observed in several western EU countries – Belgium, Austria, Germany and the Netherlands – and also in Portugal.

There were 13 NUTS level 2 regions where the employment rate for people aged 25–64 with a high level of education was less than 80.0% in 2023. These regions were exclusively located in southern EU countries: Italy, Greece and Spain. Almost all of the 13 regions in this group were characterised as rural regions, with relatively large agricultural sectors and few employment opportunities for highly skilled people. The lowest employment rate was recorded in the north-western Greek region of Dytiki Makedonia, at 66.3%.

(%, people aged 25–64, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_lfsd2pop) and (lfst_r_lfe2eedu)

A New Skills Agenda for Europe (COM(2016) 381 final) and the European Skills Agenda for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience (COM(2020) 274 final) define EU policy priorities and actions to be undertaken to improve the anticipation, development and activation of skills. The European Year of Skills 2023/24 was designed to ‘promote reskilling and upskilling, helping people to get the right skills for quality jobs’. Among their principal goals, these initiatives seek to ensure that the skills available in the labour market match those required by businesses and the economy.

A recent communication from the European Commission, Harnessing talent in Europe’s regions (COM(2023) 32 final), highlighted increasing global competition for talent, as many developed world economies are expected to face shrinking populations in the years to come. The communication identified demographic transformation as a cause for concern in several EU regions (for more information on population developments, see Chapter 1), with shrinking working-age populations and the potential departure of young and skilled workforces to other regions/territories leading to a talent development trap. With this in mind, the European Commission launched a talent booster mechanism in early 2023 with the aim of supporting EU regions that were affected by a decline in their working-age populations through training, in order to retain and attract the people, skills and competences needed to address the demographic transition.

More about the data: highly skilled people

Employed people with high-skills are defined – for the purpose of this publication – as people aged 25–64 who are employed in the following occupations: managers; professionals; or technicians and associate professionals (ISCO-08 major groups 1–3).

In 2023, there were approximately 81 million highly skilled people aged 25–64 employed within the EU; they accounted for 44.9% of the total number of employed people of the same age. Map 5 shows that the regional distribution of highly skilled people across NUTS level 2 regions was somewhat skewed: 105 out of 241 regions for which data are available, or 43.6% of all regions, reported a share of highly skilled employed people that was above the EU average.

Capital regions attract highly qualified talent

At the upper end of the distribution, there were 18 NUTS level 2 regions in 2023 where at least 60.0% of all employed people aged 25–64 were considered to be highly skilled. Looking in more detail, 13 out of these 18 regions were capitals. These regions tend to ‘pull’ highly qualified individuals through a wide array of job prospects in dynamic sectors of the economy and may also offer a diverse range of cultural and social opportunities

- the highest share was observed in the Swedish capital region of Stockholm (73.3%)

- more than 2 out of 3 employed people in the capital regions of Poland, Czechia and Denmark were considered to be highly skilled, this was the case in Luxembourg too

- the capital regions of the Netherlands, Finland, France, Lithuania, Hungary, Germany, Croatia and Belgium also reported shares that were higher than 60.0%

- there were 5 non-capital regions with shares of more than 60.0%, including the Dutch regions of Utrecht (69.8%) and Zuid-Holland (62.8%), the Belgian Prov. Brabant Wallon (65.1%) and the Swedish regions of Sydsverige (62.4%) and Västsverige (60.1%).

Many of the EU regions experiencing the impact of declining working-age populations and struggling to retain and attract highly skilled individuals are predominantly rural regions. However, outermost and peripheral regions, as well as former industrial heartlands struggling with the transition to new industrial structures are also affected. In 2023, there were 19 NUTS level 2 regions where highly skilled employed people accounted for less than 27.5% of total employment among those aged 25–64 (these regions are denoted by a yellow shade in Map 5). This group was principally concentrated in the south-eastern corner of Europe, with 9 regions in Greece, 6 in Romania and 3 in Bulgaria; the remaining region was the autonomous Spanish region of Ciudad de Melilla. The lowest regional shares of highly skilled employed people were recorded in 3 Greek regions – Sterea Elláda (20.9%) Voreio Aigaio (22.0%) and Notio Aigaio (22.4%) – and the southern Romanian region of Sud-Muntenia (21.8%). The lowest share of highly skilled employed people among western EU countries was recorded in the southern German region of Niederbayern (38.5%), while the lowest share among northern EU countries was recorded in the Finnish region of Åland (40.6%).

Map 5: Highly skilled employed people, 2023

(% of people employed aged 25–64, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (labour force survey)

Unemployment

Unemployment can have a bearing not just on the macroeconomic performance of a country or a region, for example lowering productive capacity, but also on the well-being of individuals without work and their families. Rising unemployment results in a loss of income for individuals, increased pressure on government spending for social benefits and a reduction in tax revenues. Furthermore, the personal and social costs of unemployment are varied and include a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion, debt or homelessness, while the stigma of being unemployed may have a potentially detrimental impact on (mental) health.

More about the data: the unemployment rate

Within this section, data are presented for people aged 15–74; this is the standard age range employed by Eurostat and the International Labour Organization (ILO) for studying unemployment rates within the labour force.

Contrary to what may be thought, the unemployment rate isn’t the direct opposite of the employment rate, since the 2 measures don’t have the same denominator; the unemployment rate uses the labour force and the employment rate uses the total population.

The EU unemployment rate was 6.1% in 2023

From a peak of 11.6% in 2013, the EU’s unemployment rate among people aged 15–74 fell during 6 consecutive years to 6.8% in 2019. With the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, the EU’s unemployment rate increased 0.4 percentage points in 2020, followed by almost no change in 2021, as the pandemic continued to impact some parts of the EU economy. Having witnessed a marked decrease in unemployment during 2022 – with labour shortages apparent in certain sectors of the economy – unemployment continued to fall, albeit at a relatively modest pace in 2023. There were 13.2 million unemployed people across the EU in 2023, while the unemployment rate stood at 6.1%.

Map 6 shows unemployment rates across NUTS level 2 regions in 2023: the highest rates were observed in southern EU countries, outermost regions of the EU and the Belgian capital region. By contrast, the lowest rates were largely concentrated in a cluster of regions that stretched from Germany into Poland, Czechia and Hungary. The distribution of unemployment rates exhibited a certain degree of skewness: there were 98 regions (out of 238 for which data are available) that had unemployment rates equal to or above the EU average of 6.1%, while almost 60% of all regions (140 out of 238) recorded rates that were below the EU average.

In 2023, there were 25 NUTS level 2 regions that reported unemployment rates of at least 10.5%, as shown by the darkest shade of blue in Map 6. The Spanish autonomous regions of Ciudad de Ceuta and Ciudad de Melilla were the only regions where the unemployment rate was higher than 20.0%. Leaving these 2 regions and the French outermost regions aside, the next highest unemployment rates were in Andalucía (18.3%) and Extremadura (17.4%) in the south-west of Spain and in Campania (17.4%) in Italy.

At the lower end of the distribution, there were 24 NUTS level 2 regions where the unemployment rate was less than 2.5% in 2023; these regions are shown with a yellow shade in Map 6. The lowest regional unemployment rates were concentrated in Germany, Poland, Czechia and Hungary (as noted above), while there were also relatively low rates observed in Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano/Bozen (northern Italy), Zeeland (the Netherlands) and Bratislavský kraj (the capital region of Slovakia). The lowest rate in the EU was recorded in the Czech region of Střední Čechy (that surrounds the capital of Praha), at 1.7%, while there were 5 other regions with rates that were less than 2.0%: Niederbayern (2021 data) and Schwaben in southern Germany, Warszawski stołeczny and Pomorskie in Poland, and Jihozápad in Czechia.

In 2023, Croatia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Slovakia all reported their lowest regional unemployment rate within their capital region; in Poland and Romania, the lowest rate was recorded jointly in the capital region and in 1 other region. Unemployment rates for the capital regions of the multi-regional eastern and Baltic EU countries were consistently lower than their national unemployment rates. This pattern was particularly notable in Slovakia and Romania, where the national unemployment rate was at least twice as high as the unemployment rate of the capital region.

By contrast, the highest regional unemployment rates in 2023 in Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Austria, Portugal and Finland were recorded within their capital regions. This pattern was particularly apparent in Germany, Austria and Belgium, as the unemployment rates in their capital regions were 1.7–1.9 times as high as their respective national averages.

Map 6: Unemployment rate, 2023

(% of labour force, people aged 15–74, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat

(lfst_r_lfu2gan)

In 2023, the highest regional disparities for unemployment rates were observed across Italy

Some EU countries are characterised by considerable variations in regional unemployment rates. A population-weighted coefficient of variation provides a means to analyse such intra-regional disparities (see Figure 3). Italy, Belgium, Austria, Hungary and Romania recorded the largest regional disparities in 2023, with coefficients of variation of 59.0%, 52.9%, 47.3%, 44.5% and 43.7%, respectively

- in Italy, the highest regional unemployment rate was recorded in Campania (17.4%) and the lowest in Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano/Bozen (2.0%), with a clear north–south divide

- in Belgium, the highest regional unemployment rate was recorded in Région de Bruxelles-Capitale / Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest (10.6%) and the lowest in Prov. West-Vlaanderen (2.8%), with a clear divide between the regions of Région wallonne and Vlaams Gewest

- in Austria, the capital region of Wien had by far the highest regional unemployment rate (9.6%), while the lowest rates – no more than 3.5% – were observed in the westernmost regions of Salzburg, Tirol, Vorarlberg and Oberösterreich

- in Hungary, the highest unemployment rate was recorded in the north-eastern region of Észak-Alföld (6.7%), while the lowest rates were recorded in the north-western region of Közép-Dunántúl (2.1%) and the capital region of Budapest (2.3%)

- in Romania, the highest regional unemployment rate was recorded in Sud-Est (9.1%), while the lowest rates were in Vest and the capital region of Bucureşti-Ilfov (both 2.8%).

At the other end of the range, the lowest regional disparities – with coefficients of variation below 10.0% – were observed in Finland and Denmark. For example, the highest regional unemployment rate in Finland was recorded in Helsinki-Uusimaa (7.6%) and the lowest in Länsi-Suomi (6.7%).

Figure 3 also shows that regional disparities for unemployment rates were marginally lower across the EU as a whole in 2023 than in 2013, as the coefficient of variation fell from 64.9% to 62.5%. During this period, regional disparities increased in relative terms at their most rapid pace in Hungary and Greece, as their coefficients of variation approximately doubled. By contrast, regional disparities for unemployment rates decreased in 5 out of 17 EU countries for which data are available. The most rapid convergences in regional unemployment rates were observed in Finland, Germany and Portugal.

(coefficient of variation in %, people aged 15–74, by NUTS 2 regions)

Source: Eurostat (lfst_r_lmdur)

Source data for figures and maps

Data sources

The information presented in this chapter relates to annual averages derived from the labour force survey (LFS). Eurostat compiles and publishes labour market statistics for the EU, individual EU countries, as well as EU regions. In addition, data are also available for several EFTA countries – Iceland, Norway and Switzerland – and candidate countries – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Türkiye – and their statistical regions. The LFS population generally consists of people aged 15 or over living in private households; definitions are aligned with those provided by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

LFS microdata are collected through a survey to obtain information on an individual’s demographic background, labour status, employment characteristics of their main job, hours worked, employment characteristics of their 2nd job (if relevant), time-related underemployment, the search for employment, education and training, previous work experience of people not in employment, their situation a year before the survey, their main labour status and their income. These statistics are aggregated by region and are generally published down to NUTS level 2. Some regional labour market statistics are compiled/transmitted for NUTS level 3 regions, although this is on a voluntary basis.

When evaluating regional information from the LFS, it is important to bear in mind that the information presented relates to the region where the respondent has his/her permanent residence and that this may be different to the region where their place of work is situated as a result of commuter flows.

The collection of LFS data up to and including reference year 2020 was conducted by national statistical authorities in accordance with Council Regulation (EEC) No 577/98. A new legal basis was introduced for LFS data from 2021 onwards: Regulation (EU) 2019/1700 establishing a common framework for European statistics relating to persons and households, based on data at individual level collected from samples. Furthermore, Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2240 specifies the technical items of the dataset, establishing the technical formats for transmission of information and specifying the detailed arrangements and content of the quality reports on the organisation of the sample survey in the labour force domain. This change in legal basis implies a break in series between 2020 and 2021; results obtained before and after 1 January 2021 are consequently not fully comparable.

Some countries have other quality concerns that may impact geographical comparability.

- Spain and France use slightly different definitions to those provided by the regulation.

- Changes in survey methodology led to a break in series for German data in 2020. Therefore, data for Germany shouldn’t be compared directly with that for previous years. In addition, data collection during 2020 was impacted by technical issues and COVID-19 measures and hence there is a low degree of reliability for some regions. For more information, see this methodological note.

- The labour force survey sample for Corse (in France) was too small to have reliable regional results, while Mayotte (also France) is covered by a specific annual survey. As a result, data for these 2 regions should also be considered with caution.

Indicator definitions

Employed people

In the context of the LFS, an employed people include those aged 15–89 who, during the reference week, performed work – even if just for 1 hour – for pay, profit or family gain. Alternatively, the person wasn’t at work, but had a job or business from which they were temporarily absent due to illness, holiday, maternity or paternity leave, job-related training or short or paid parental leave. This definition follows resolutions of the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (the ICLS is hosted by the ILO). Within this publication, most labour force indicators are for a narrower definition of core working-age people, namely people aged 20–64.

Employment rate

The employment rate is the percentage of employed people in relation to the comparable total population. For the overall employment rate, the comparison is generally made within the population of core working-age people (defined within this publication as people aged 20–64).

Employment rates may also be calculated for a particular age group and/or sex – for example, males aged 15–29. The gender employment gap is defined as the employment rate of men minus the employment rate of women among people aged 20–64. In a similar vein, employment rates may also be calculated for other subpopulations according to a range of socioeconomic criteria, for example, employment rates by level of educational attainment. Within this publication, the employment rate of people with different levels of educational attainment concern people aged 25–64 who had completed

- no more than a lower secondary education (as defined by the international standard classification of education (ISCED) levels 0–2)

- an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (as defined by ISCED levels 3–4)

- a tertiary level of education (as defined by ISCED levels 5–8) – in other words, people who had completed a short-cycle tertiary education, bachelor’s, master’s or doctoral degree (PhD).

Highly skilled employed people

The most commonly used approaches for measuring the demand for skills include making use of data on qualifications (educational attainment) or occupations. Both of these datasets are available from within the LFS; this publication gives preference to data based on occupations.

Data on occupations provide indications of the type of jobs undertaken by people in employment. Occupations are considered to be a good indirect measure for skills demand and their distribution across an economy. The international standard classification of occupations (ISCO) allocates jobs to occupations, based on a description that takes into account the level of qualifications and the types of tasks to be carried out. Highly skilled employed people are defined as people employed as managers (ISCO 01), professionals (ISCO 02), technicians and associate professionals (ISCO 03). To have consistency with the age classes presented for alternative indicators about qualifications and skills and to exclude younger people who may not have had the prospect/opportunity of getting a job requiring a high-skill level, the data for this indicator are shown for people aged 25–64. The indicator is defined as the share of highly skilled employed people in the total number of employed people; the indicator excludes people who gave no response when asked about their occupation.

Labour force

The labour force includes all people who were either employed or unemployed during the reference week. This aggregate includes all people offering their work capacity on the labour market: as such it reflects the supply side of the market.

Regional disparities in labour force indicators

Regional labour market disparities are based on the population-weighted coefficient of variation. Calculations are made only for EU countries that have more than 4 NUTS level 2 regions. As such, data aren’t presented for Estonia, Ireland, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovenia and Slovakia. The coefficient of variation for the whole of the EU includes all regions in the EU, not just those of EU countries that have more than 4 NUTS level 2 regions.

Unemployed people

Eurostat‘s unemployment statistics are based on resolutions of the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (the ICLS is hosted by the ILO). Unemployed people are defined as those aged 15–74 who are without work, but who have actively sought employment in the 4 weeks preceding the reference week (or have already found a job to start within the subsequent 3 months) and are available to begin work within the following 2 weeks.

Unemployment rate

The unemployment rate is defined as the number of unemployed people expressed as a percentage of the total labour force.

Young people neither in employment nor in education or training (NEET)

The share of young people who are neither in employment nor in education and training, abbreviated as NEET, corresponds to the share of the population (of a given age group and sex) that isn’t employed and not involved in further (formal or non-formal) education or training during the 4 weeks preceding the survey. The numerator refers to people meeting these 2 conditions, while the denominator is the total population (of the same age group and sex), excluding those respondents who didn’t answer the question in the survey about participation in regular (formal) education and training. For the purpose of this publication, the share of young people neither in employment nor in education or training relates to those aged 15–29.

Context

There are 6 European Commission priorities for 2019–24, including the creation of ‘An economy that works for people’, whereby the EU seeks to create a more attractive investment environment and growth that creates quality jobs, especially for young people and small businesses. Some of the principal challenges outlined by President von der Leyen include: fully implementing the European Pillar of Social Rights; ensuring that workers have at least a fair minimum wage; promoting a better work-life balance; tackling gender pay gaps and other forms of workplace discrimination; getting more disabled people into work; and protecting people who are unemployed.

Since the end of 2019, the European Commission has contributed to the implementation of the social pillar principles with, among other initiatives, the following.

- The European Gender Equality Strategy 2020–25. In March 2023, the European Commission launched a campaign to challenge gender stereotypes affecting both men and women in different spheres of life, including career choices, sharing care responsibilities and decision-making.

- Council Regulation (EU) 2020/672 on the establishment of a European instrument for temporary support to mitigate unemployment risks in an emergency (SURE) following the COVID-19 outbreak was designed to help protect jobs and workers by avoiding wasteful redundancies and long-term negative consequences for labour markets through action to sustain incomes and preserve the productive capacity and human capital of enterprises and the economy as a whole.

- The Just Transition Fund is designed to alleviate the social and economic costs resulting from the transition towards a climate-neutral economy.

- A Directive on adequate minimum wages in the European Union (EU) 2022/2041 aims to improve living and working conditions, in particular through upward social convergence, reduced wage inequality, the promotion of collective wage bargaining and minimum wage protection.

- Young people were particularly impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. The Youth Employment Support action is designed to give young people opportunities to develop their full potential to shape the future of the EU and thrive in the digital and green economy of the future. It reinforces the Youth Guarantee, provides attractive vocational education and training opportunities, a renewed impetus for apprenticeships, and measures to support youth employment through start-ups and young entrepreneur networks.

The European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) is the EU’s main instrument dedicated to investing in people. It aims to build a more social and inclusive EU. Regulation (EU) 2021/1057 establishing the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) entered into force in July 2021, providing a key financial instrument for implementing the European Pillar of Social Rights and supporting the post-pandemic recovery. The ESF+ has a total budget of €99.3 billion for the period 2021–27 and aims to support people by creating and protecting job opportunities, promoting social inclusion and fighting poverty; it has ambitious goals for investing in young people and addressing child poverty. It also aims to encourage high employment levels, fair social protection and a skilled and resilient workforce ready for the transition to a green and digital economy.

New digital and green technologies will likely bring about a rapid transformation in the types of jobs that are available and different ways of working. As such, policymakers are seeking ways to promote investment in skills and training so that the EU has a workforce with the necessary skills to boost innovation, improve competitiveness, and contribute towards sustainable growth. The European Year of Skills was launched in 2023 and extended into 2024, with various stakeholders working together to promote skills development

- helping people to get the right skills for quality jobs

- promoting investment in training and upskilling, enabling people to stay in their current jobs or find new ones

- matching people’s aspirations and skills set with opportunities on the job market, especially for the green and digital transitions and the economic recovery

- helping businesses, in particular small and medium-sized enterprises, to address skills shortages, while ensuring workforce skills match the needs of employers, by closely cooperating with social partners and business

- attracting people from outside the EU with (additional) skills that are needed to drive forward sectors that have been identified as having strategic relevance.

Direct access to

- Employment – annual statistics

- EU labour force survey – online publication

- EU labour force survey statistics – online publication

- Flexibility at work – statistics

- Labour market flow statistics in the EU

- Labour market slack – employment supply and demand mismatch

- Main place of work and commuting time – statistics

- Participation of young people in education and the labour market

- Self-employment statistics

- Unemployment statistics

- Unemployment statistics and beyond

- Unemployment statistics at regional level

- Regional labour market statistics (t_reg_lmk)

- Unemployment rate by NUTS 2 regions (tgs00010)

- LFS main indicators (t_lfsi)

- LFS series – detailed annual survey results (t_lfsa)

- LFS series – Specific topics (t_lfst)

- Regional labour market statistics (reg_lmk)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Employment – LFS series (lfsa_emp)

- Employment rates – LFS series (lfsa_emprt)

- Total unemployment – LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- LFS series – Specific topics (lfst)

- LFS regional series (lfst_r)

- Regional population and economically active population – LFS annual series (lfst_r_lfpop)

- Regional employment – LFS annual series (lfst_r_lfemp)

- Regional unemployment – LFS annual series (lfst_r_lfu)

- Regional labour market disparities – LFS series and LFS adjusted series (lfst_r_lmd)

- LFS regional series (lfst_r)

Manuals and further methodological information

- Annual quality reports for the EU labour force survey

- EU labour force survey – online publication

- Methodological manual on territorial typologies

- Statistical regions in the European Union and partner countries: NUTS and statistical regions 2021 – 2022 edition

Metadata

- Regional labour market statistics (ESMS metadata file – reg_lmk_esms)

- European Commission – Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion, see

- European Commission – A New Skills Agenda for Europe (COM(2016) 381 final)

- European Commission – European year of skills 2023/24

- European Commission – Harnessing talent in Europe’s regions (COM(2023) 32 final)

- European Commission – The European Pillar of Social Rights in 20 principles

- International Labour Organisation (ILO) – Statistics and databases – Standards and guidelines on labour statistics

- OECD – Active labour market policies

This article forms part of Eurostat’s annual flagship publication, the Eurostat regional yearbook.

Maps can be explored interactively using Eurostat’s Statistical Atlas.