Participation of young people in education and the labour market

Data extracted in September 2023

Planned article update: September 2024.

Highlights

This article focuses on the complex interplay between participation in formal education and in the labour market in the European Union (EU).

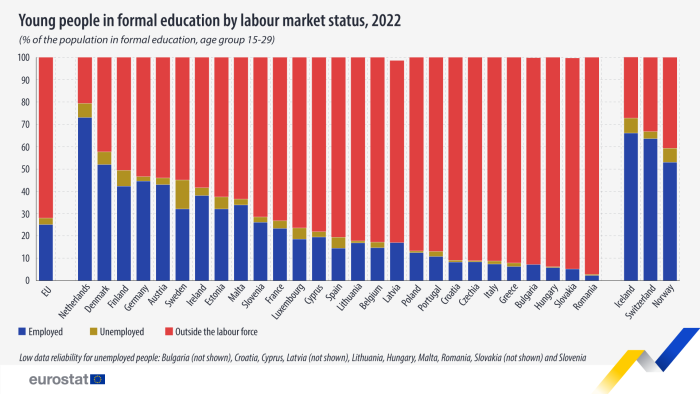

In the case of young people, participation in formal education and in the labour market interact in complex ways going beyond a straightforward one-way transition from school to work. A share of young people start working, e.g. in the form of part-time, weekend or student jobs, while still participating in formal education. It is indeed possible to be in formal education and on the labour market at the same time, leading to an overlap. It is important to be aware of these possibilities when interpreting and assessing youth unemployment rates.

According to the United Nations definition, young people, for statistical purposes, refer to the age group 15-24 years. However, the age category 15-29 years also deserves attention as it was considered the reference in the context of the European Year of Youth (2022). For this reason, the current article provides information regarding young people aged 15-29 years. Concurrently, data on people aged 15-34 years is also presented in order to cover the transition from formal education to the labour market more extensively.

The article shows the results for the EU as a whole and compares results across all EU Member States, three EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) and one candidate country (Serbia).

Full article

Participation of young persons in formal education and in the labour market

As young people grow older, there is a decrease in their share in education. Not all leave education at the same age; the decrease pace could be determined by national systems of education and training, as well as other factors such as national labour market characteristics and cultural determinants.

Whilst the decrease in the share of young people in formal education can be observed, an increase in those participating in the labour market, both as employed or unemployed, also emerges from the data.

The pace of exit from education differs from the pace of entry onto the labour force, as some people are in education and in the labour force at the same time, while others move out of education and stay outside the labour force.

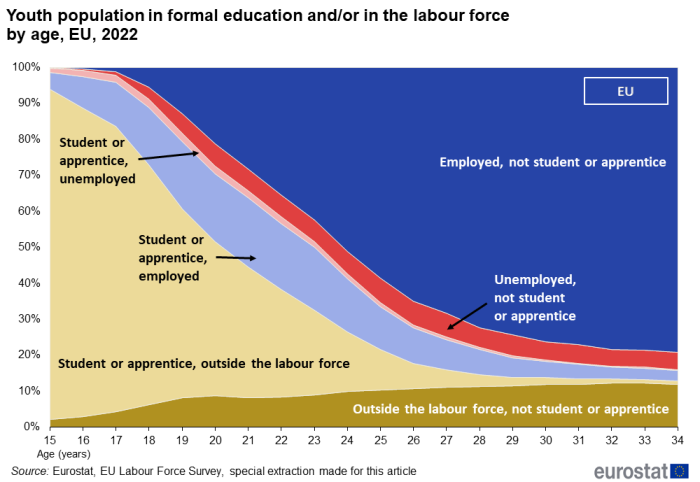

Figure 1 below shows a schematic presentation of the shares in participation of young people aged 15 to 34 years old in formal education and in the labour market at each age.

- All those employed or unemployed are classified as being in the labour force, and are represented by a blue colour (dark or light blue).

- All those who declared to have been in formal education or training, during the previous four weeks, are considered as being a student or apprentice and are represented by a light colour (light blue or light yellow).

- Finally, those who are outside the labour force are represented by the yellow colour (dark or light yellow).

An interesting group includes those who are both in formal education or training and in the labour force. In the schematic representation, this overlap is represented by a light blue colour.

Please consider that persons who exclusively participated in non-formal training sessions, such as attending a course, a seminar or taking private lessons, are not included and can appear either in the category 'Persons outside the labour force, not student or apprentice' or 'Persons in the labour force, not student or apprentice'[1].

The overlaps between education and labour force participation reflect a wide range of situations. For some young people, employment is subordinate to education; for example, in the case of students who work for just a few hours a week (e.g. students working at weekends or in the evenings after classes). Others are employed and enrolled in a formal education programme at the same time and with the same purpose. Furthermore, education can be subordinate to employment as other people study after work to qualify for a diploma. In the case the same activity counts as both education and employment - e.g. apprenticeships, paid traineeships (if part of a formal education programme)[2], or specific vocational training phases integrated into some study programmes in tertiary education – and in line with the EU LFS definitions, paid trainees are classified as employed, but unpaid trainees are not.

The status of young people in the labour force can be further disaggregated at EU level, to make a clear distinction between the employed and unemployed (Figure 2). The figure shows that the number of employed people increases and the number of those outside the labour force decreases; however, the overall number of unemployed youth remains unvaried across the ages. More specifically, whilst the number of students or apprentices who are unemployed decreases by age, the overall number of youth unemployment remains approximately the same.

The following section of this article analyses country differences regarding those patterns.

Country differences

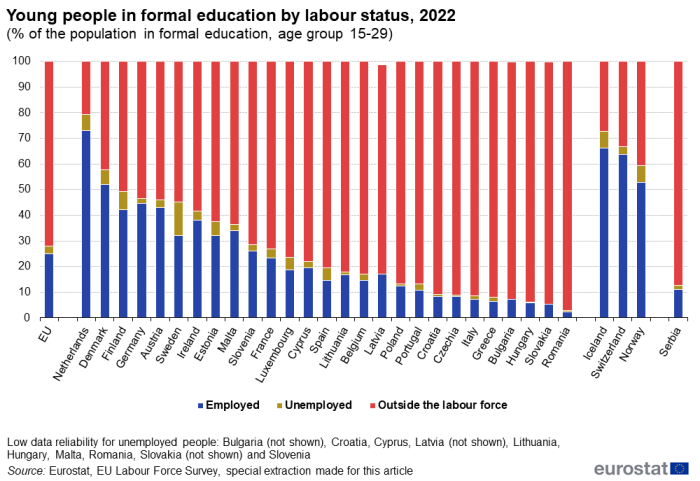

There are significant structural differences among European countries in young people's participation in the labour market. The reason is a combination of various factors, including the availability of opportunities to work while studying and the differences in the national systems of education and training - for details, see Eurydice - Description of national educational systems and policies.

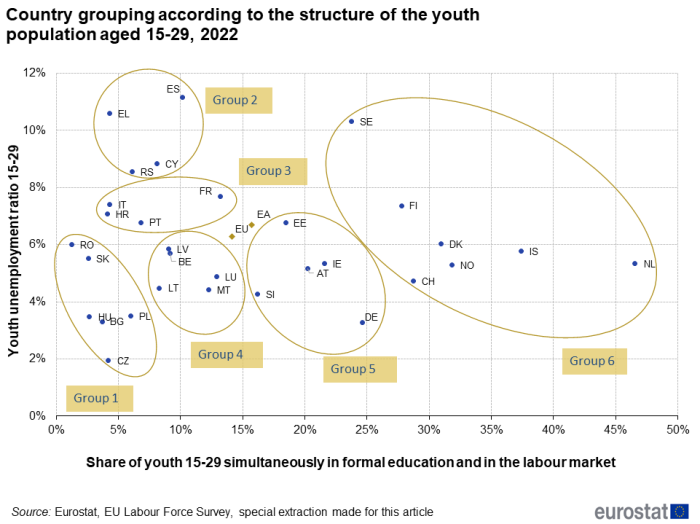

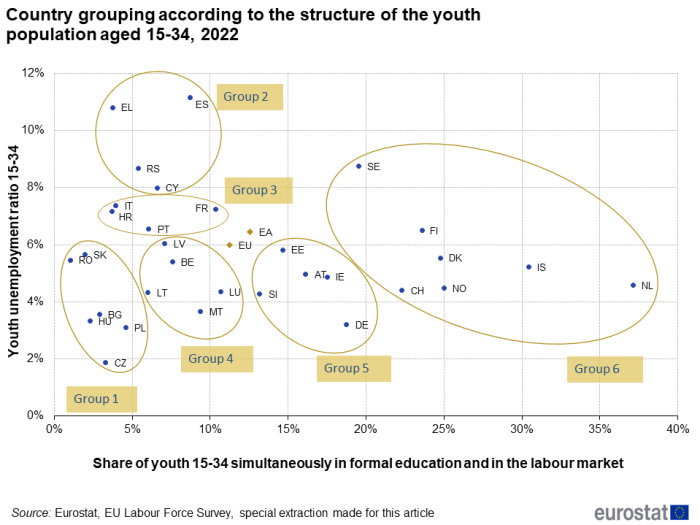

Each country's characteristics and trends are unique, but it is possible to cluster countries according to common results and features. Figure 3 (age group 15-29) and Figure 4 (age group 15-34) plot the situation of all countries participating in the EU-LFS according to two parameters. The first parameter consists of the degree to which those in education are simultaneously in the labour market (horizontal axis) and the second parameter is the level of youth unemployment, measured in terms of the youth unemployment ratio (vertical axis). Figures 3 and 4 highlight six groups of countries.

Overall, it is relevant to notice that, compared with 2021 data, Cyprus moved from group 3 to group 2. In Cyprus, significant changes can be observed in the share of youth aged 15-29 years simultaneously in education and in the labour market (8.1 % in 2022, compared with 6.9 % in 2021). This shift is also due to the change of position of other countries from the same cluster in the chart. In particular, Italy's youth unemployment ratio, for both age groups, was significantly above 8 % according to 2021 data, while, in 2022, it is below 8 % (7.4 % for both age groups). Youth unemployment ratio also noticeably changed in Serbia, where it decreased from 10.0 % (both age groups, 2021) to 8.6 % (15-29, 2022) and 8.7 % (15-34, 2022).

In addition to such shifts, group 6 has seen the most changes from one year to the next. Findings from Sweden and the Netherlands affected the size of the whole group and impacted on other groups in the chart. In 2022, youth unemployment ratio for the age group 15-29 was 10.3 % while it was 8.7 % for the other age group, both lower than the previous year. In the Netherlands, the share of youth 15-29 simultaneously in education and in the labour market varied from 42.4 %, in 2021, to 46.6 %, in 2022. At the same time, for the age group 15-34 years, the share of youth both in education and in the labour market, significantly increased (37.1 % in 2022, compared with 34.0 % in 2021).

Furthermore, an increase of about 2 percentage points (pp), from 2021 to 2022, in the share of youth aged 15-29 years simultaneously in education and in the labour market, was also recorded for Estonia (group 5). Conversely, in Spain (group 2), whilst the share of youth both in education and in the labour market remained almost unchanged, for both age groups between 2021 and 2022, the youth unemployment ratio considerably increased (about 2 pp).

As a general conclusion for 2022, it can be observed that, in Scandinavian countries, together with the Netherlands and Switzerland, the labour market is very dynamic. It not only records interesting improvements in the youth unemployment ratio over a year, but it also offers opportunities for simultaneous participation in education and labour market. In this group, Sweden is the least performing country both in terms of simultaneous participation in education and labour market (19.6 %, 15-34 years age group) and youth unemployment ratio (8.7 %, 15-34 years age group, greater than the EU average of 6.0 %). In the 15-29 years age group, in Sweden, there are even greater deviations from the EU average and a greater difference between its share of youth participation in education and in the labour market (23.8 %) and youth unemployment ratio (10.3 %).

In other countries (such as those in groups 1, 4 and 5), in the age group 15-34 years, the youth unemployment ratio is less than or equal to the EU average (6.0 %). However, the mobility of young students in the labour market is low, with important differences between countries of the group 5 and group 1. In the group 5, the share of youth simultaneously in education and in the labour market is above the EU average of 14.1 % (15-29) and 11.2 % (15-34) with very high values for Ireland and Germany in both age groups. In the group 1, instead, there are very low values for the participation of young people in both education and the labour market, where the lowest shares were recorded in Romania and Slovakia (1.0 % and 2.0 %, respectively, for the age group 15-34 years).

Countries belonging to group 2 and 3 are in a very peculiar situation. Their youth unemployment ratio is on average higher that the EU average, for both age groups. At the same time, in these countries, simultaneous participation in education and the labour market is still very difficult and remains lower than the EU average, in both age groups. In these groups, only France performed relatively better with a share of 13.2 % (15-29) out of the EU average of 14.1 %, and 10.3 % (15-34) out of the EU average of 11.2 %.

The following charts illustrate the situation of some countries as representatives of their own groups.

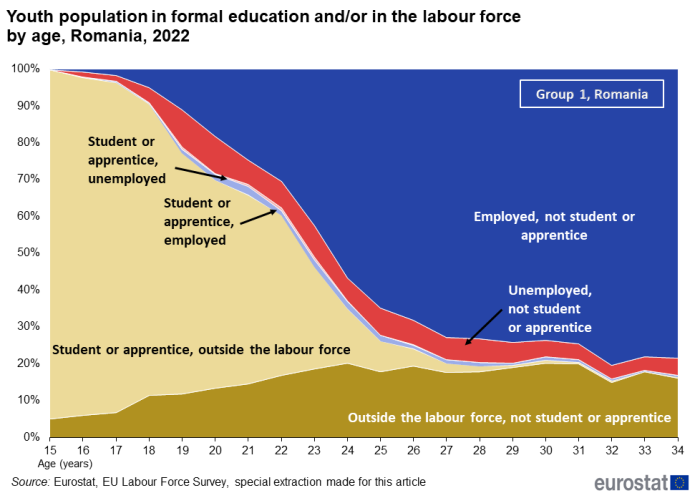

Group 1: the first group of countries has very few students who are employed or unemployed. For countries in this group, the overlap between the labour force and education is very small. This could be the case if young people complete their studies before looking for a first job, and there are only few quality part-time or student jobs available. It could include those who quit studies and start working or who cannot prioritise education over employment as they need to work to make a living.

Countries in this group include Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechia and Poland. Romania is shown in Figure 5 as an example.

Note that for countries in this group, the youth unemployment rate may be high even if the absolute number of youth unemployment is low, the reason being a very small labour market for the young people.

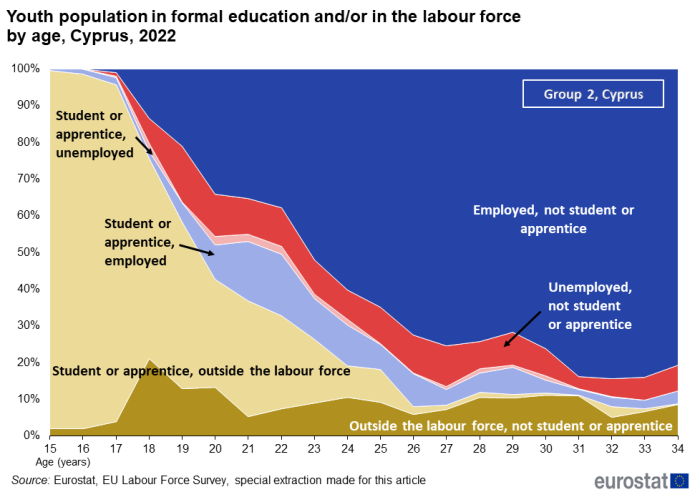

Group 2: the second group of countries features a relatively low overlap between education and the labour market for the same reasons mentioned above. They also have the highest level of youth unemployment compared with all other country groups, particularly Greece and Spain. The latter is the country with the highest overlap between education and the labour market, but also highest youth unemployment.

Countries in this group include Cyprus, Greece, Spain and Serbia. Cyprus is shown in Figure 6 as an example of irregular or sudden variations in the young population in education and/or employment across the ages.

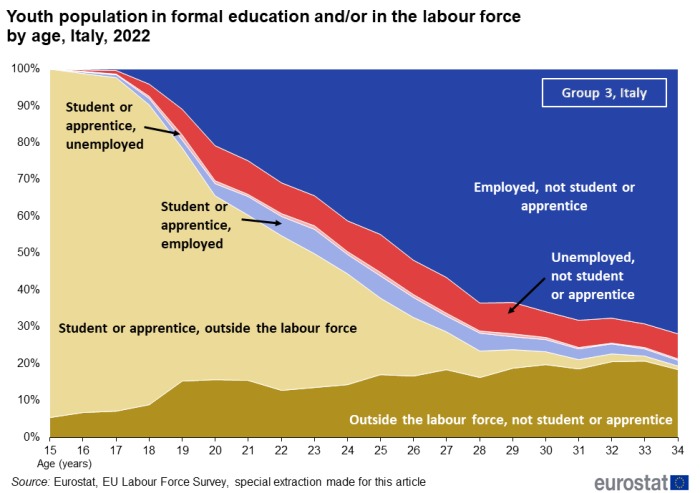

Group 3: the third group gathers countries with a relatively high level of youth unemployment, which is above the EU average for both age groups. At the same time, in the countries belonging to this group (Italy, Croatia, France and Portugal), participation of students in the labour market is relatively low, with significant differences across countries. For example, the share of youth simultaneously in education and in the labour market is much higher in Italy – which is shown as an example in Figure 7 – than France. Please note that the number of young unemployed people in education is marginal compared with the number of young unemployed people not in education.

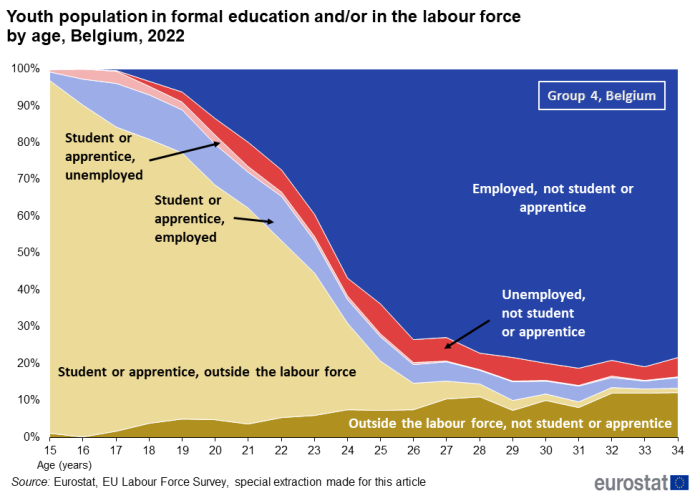

Group 4: The fourth group of countries has two features: a relatively low to moderate overlap between education and the labour force and youth unemployment levels that are below the EU average. This group includes Belgium, Luxembourg, Lithuania, Latvia and Malta. Belgium is shown as an example in Figure 8. The number of young unemployed people in education is marginal and decreases by the age compared with the number of young unemployed people not in education, but the latter is less prominent than in group 3.

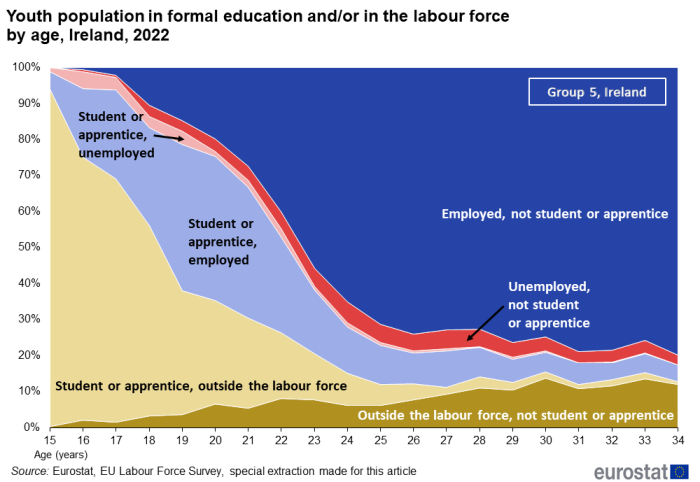

Group 5: The fifth group of countries has high levels of employment among those in education and low levels of unemployment among those in education. In some countries, this is due to the established system of apprenticeship in the secondary education. For example, in this group, Germany is the country with the lowest levels of youth unemployment and the highest participation of students in the labour market.

This group gathers Austria, Slovenia, Ireland, Estonia and Germany. In Figure 9, Ireland is shown as an example of a large band of young people both in education and employment (light blue).

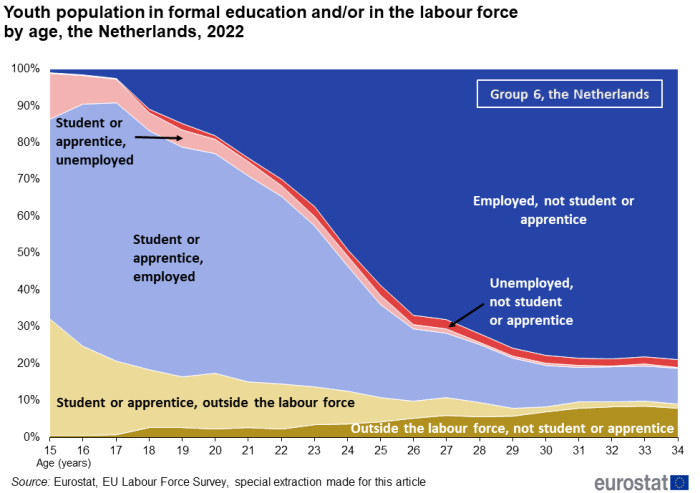

Group 6: The final group of countries displays a very high participation of students in the labour market and levels of unemployment below the EU average except for Finland and Sweden. This group includes Finland, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland.

These countries have a long-standing tradition of students doing part-time, weekend or student jobs (generally speaking, Nordic countries have strong seasonal employment). Furthermore, some countries, e.g. the Netherlands, have dual study programmes in specific fields of tertiary education that include periods of practical work. In this group of countries, young people start looking for jobs at a very early age; as a result, there is sizeable unemployment among very young students, but this decreases by the age. In some countries, such as Sweden, there is a poor participation of students to the labour market compared with the other countries in the same group.

Figure 10 shows the example of the Netherlands, where the band of young people both in education and employment (light blue) is visibly very large and the largest in this group of countries, and in the European Union and EFTA countries, as shown in Figure 11 here below.

Differences between men and women

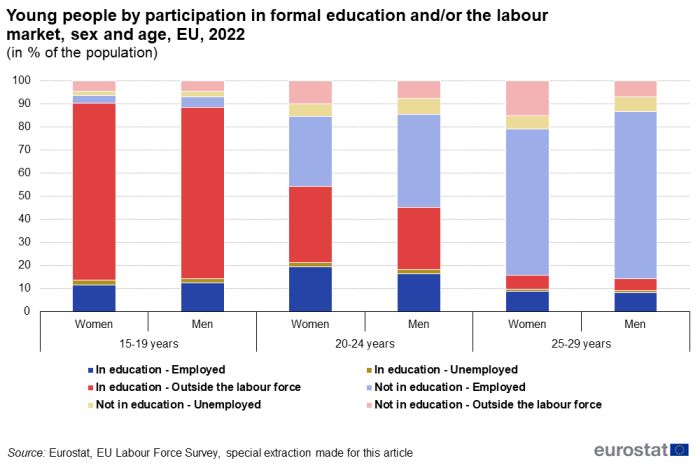

There are considerable differences between young men and women regarding their participation in formal education and labour market (Figure 12).

Considering only the involvement in education, the shares of women participating in formal education were higher than those of men. This finding is particularly true for the age group 20-24 years. In the same age group, the share of women both in education and employment is 19.2 % compared with 16.4 % in the male population.

Furthermore, there are considerably less women than men (20-24 years) in employment but not in education, with a difference of about 9 pp for 20-24 years and 25-29 years age groups.

Lastly, the share of women not in education and outside the labour force is significantly higher then the share of men, particularly in the 25-29 years age group (15.3 % for women and 6.9 % for men). This share of the population does not participate in the labour market or the formal education system.

Source data for tables and graphs

Methods and definitions

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on the European labour force survey (EU-LFS).

Source: The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15-89 years as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between the countries. The EU-LFS is an important source of information about the situation and trends in the national and EU labour markets. Each quarter around 1.8 million interviews are conducted throughout the participating countries to obtain statistical information for some 100 variables. Due to the diversity of information and the large sample size, the EU-LFS is also an important source for other European statistics like Education statistics or Regional statistics.

Reference period: Yearly results are obtained as averages of the four quarters in the year.

Coverage: The results from the EU-LFS currently cover all European Union Member States, the EFTA Member States of Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, as well as the candidate countries Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey. However, at the time of writing this article, 2021 EU-LFS data were not yet available for Montenegro, North Macedonia and Turkey. For Cyprus, the survey only covers the areas of Cyprus controlled by the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of 27 EU Member States. If data are unavailable for a country, the calculation of the corresponding aggregates takes into account the data for the same country for the most recent period available. Such cases are indicated.

Country codes: Belgium (BE), Bulgaria (BG), Czechia (CZ), Denmark (DK), Germany (DE), Estonia (EE), Ireland (IE), Greece (EL), Spain (ES), France (FR), Croatia (HR), Italy (IT), Cyprus (CY), Latvia (LV), Lithuania (LT), Luxembourg (LU), Hungary (HU), Malta (MT), the Netherlands (NL), Austria (AT), Poland (PL), Portugal (PT), Romania (RO), Slovenia (SI), Slovakia (SK), Finland (FI), Sweden (SE), Montenegro (ME), North Macedonia (MK), Serbia (RS) and Türkiye (TR).

Country notes

In the Netherlands, LFS data remains collected using a rolling reference week instead of a fixed reference week, i.e. interviewed persons are asked about the situation of the week before the interview rather than a pre-selected week.

Definitions

The concepts and definitions used in the EU-LFS follow the 19th Resolution of the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS).

Employed persons are persons aged 15-89 years who, during the reference week, performed work, even for just one hour, for pay, profit or family gain or were not at work but had a job or business from which they were temporarily absent for reasons such as illness, holiday and job-related training.

Unemployed persons are persons aged 15-74 years who were not employed during the reference week, but who were available for work immediately, and were either actively seeking work in the past four weeks or had already found a job to start within the next three months.

The labour force comprises both employed and unemployed persons. People outside the labour force are those classified neither as employed nor as unemployed.

People in education in this article refers to people in formal education during the four weeks preceding the interview. Formal education and training is defined by UNESCO as 'education that is institutionalised, intentional and planned through public organisations and recognised private bodies and — in their totality — constitute the formal education system of a country' [3].

Non-formal education and training, i.e. any organised and attended learning activities outside the formal education system, are excluded from the analyses of this article. For further information on participation in non-formal education and training see the article on adult learning statistics.

Time series

Regulation (EU) 2019/1700 came into force on 1 January 2021 and induced a break in the EU-LFS time series for several EU Member States. In order to monitor the evolution of employment and unemployment despite of the break in the time series, Member States assessed the impact of the break in their country and computed impact factors or break corrected data for a set of indicators. Break corrected data are published on the Eurostat website for the LFS main indicators.

Additional methodological information

More information on the EU-LFS can be found via the online publication EU Labour Force Survey, which includes eight articles on the technical and methodological aspects of the survey. The EU-LFS methodology in force from the 2021 data collection onwards is described in methodology from 2021 onwards. Detailed information on coding lists, explanatory notes and classifications used over time can be found under documentation.

Context

The EU Youth Strategy [1] is the framework for EU youth policy cooperation for 2019-2027. It sets 11 European Youth Goals and among them quality employment is set as one of the objectives.

Focus on young people is also highlighted in the European Pillar of Social Rights European Pillar of Social Rights, which sets out 20 key principles and rights essential for fair and well-functioning labour markets and social protection systems. Principle 4 ('Active support to employment') states that 'young people have the right to continued education, apprenticeship, traineeship or a job offer of good standing within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving education'.

In October 2020, all EU countries have committed to the implementation of the reinforced Youth guarantee in a Council Recommendation which steps up the comprehensive job support available to young people across the EU and makes it more targeted and inclusive.

Direct access to

- EU Labour Force Survey — online publication

- Youth in Europe

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2020, 2022 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2020, 2022 edition

- European Union Labour Force Survey - selection of articles (Statistics Explained)

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

Notes

- ↑ For the purpose of this article, the definition of people neither in education nor in employment is different from the one for NEET where people both in formal and/or in non-formal education and training are considered as being in education or training (for more information on this category of young people, refer to the article 'Statistics on young people neither in employment nor in education or training').

- ↑ Apprentices and trainees have been defined in detail in the EU Labour Force Survey Explanatory Notes in line with the regulations in force from 1 January 2021.

- ↑ International Standard Classification of Education 2011, paragraph 36, page 11.