Data extracted in January 2025.

Planned article update: January 2026.

Highlights

Between 2014 and 2024, the euro depreciated overall by 4.9% against the Chinese renminbi-yuan, 18.5% against the United States dollar and by 21.6% against the Swiss franc.

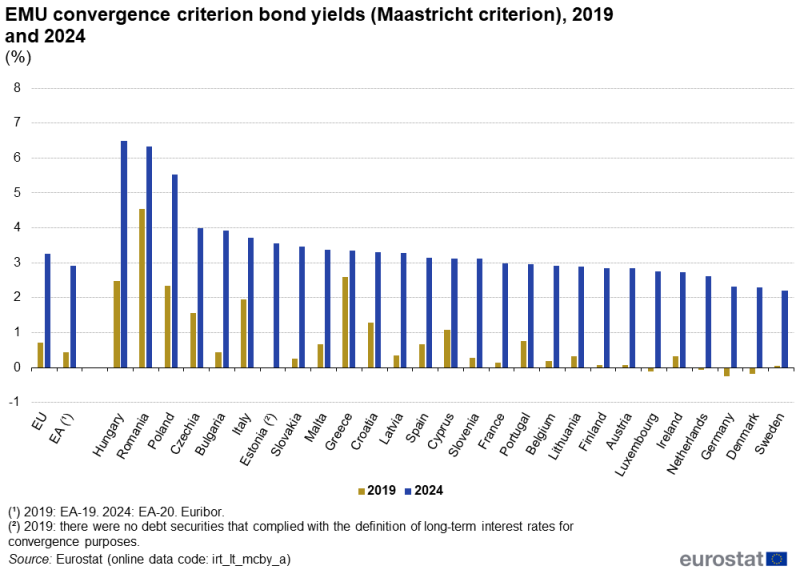

In 2024, the highest Maastricht criterion bond yields were recorded in Hungary (6.50%), Romania (6.32%) and Poland (5.53%). The lowest yields were recorded in Sweden (2.20%).

Exchange rates against the euro, 2014–24

This article presents an analysis of exchange rates and interest rates, which are some of Eurostat’s most frequently updated statistics. It is important to note that practically all of Eurostat’s data in monetary terms are denominated in euro (€), including statistics for European Union (EU) countries that aren’t part of the euro area (EA) (hereafter referred to as non-euro area countries) and data for non-EU countries. This information is derived by converting data in national currencies to data in euro using exchange rates (EUR – see currency codes). As such, for most of the monetary statistics that are released by Eurostat, it is necessary to bear in mind the possible effect of currency fluctuations when making comparisons across countries for indicators denominated in euro terms, in particular when analysing time series.

This article starts by considering the development of exchange rates across the EU, as well as exchange rate fluctuations between the euro and several currencies of non-EU countries, in particular the United States dollar, Japanese yen, the (British) pound sterling, Chinese renminbi-yuan and Swiss franc (all of which are important reserve currencies and/or commonly used for denominating international loans).

The second half of the article examines interest rates – in other words, the cost of lending/borrowing money. At the macroeconomic level, key interest rates are generally set by central banks as a primary tool for monetary policy with the goal of maintaining price stability.

Exchange rates

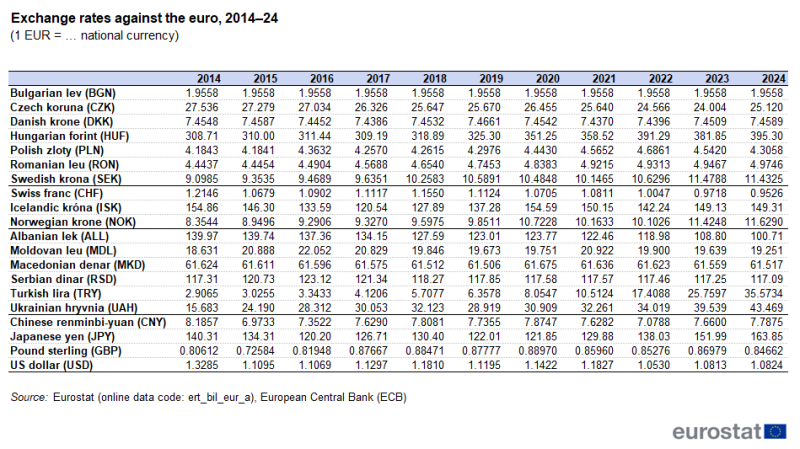

Table 1 shows the annual average exchange rates between the euro and a selection of European currencies, as well as the Chinese renminbi-yuan, the Japanese yen and the United States dollar, between 2014 and 2024. The development of these exchange rates is also shown in the 4 different charts (Figures 1a to 1d) that make up Figure 1, where the currencies are grouped together according to the magnitude of their various exchange rates against the euro. Non-euro area countries may fix their exchange rates against the euro as part of the exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) in preparation for joining the euro area, and this explains some of the very stable euro exchange rates. The current members of ERM II are Bulgaria (since 10 July 2020) and Denmark (since 1 January 1999). This article refers to data up to 2024.

(1 EUR = … national currency)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a), European Central Bank (ECB)

Focusing on the exchange rates of non-euro area EU countries, between 2014 and 2024 the euro appreciated most strongly against the Hungarian forint (28.0%), the Swedish krona (25.7%) and the Romanian leu (11.9%); notably smaller appreciations were recorded for the Polish zloty (2.9%) and the Danish krone (0.1%). The euro had an overall depreciation of 8.8% against the Czech koruna. The exchange rate between the euro and the Bulgarian lev was unchanged during the period under consideration as the lev has been pegged to the euro since its launch in 1999.

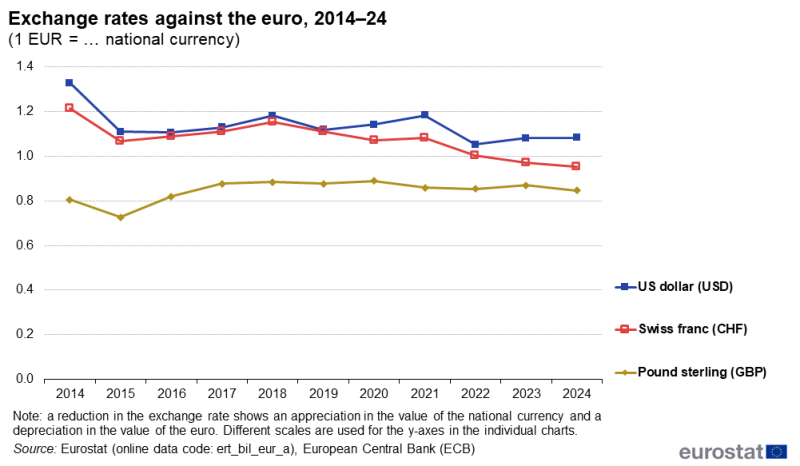

In Figure 1 (parts 1a to 1d), exchange rates against the euro for 2014–24 are shown for the countries listed in Table 1. The countries are grouped in the different figures (Figures 1a–1d) depending on their national currency’s exchange rate against the euro in 2024. Different scales are used for the y-axes in each part of the figure. A fall in the exchange rate shows an appreciation in the value of the national currency and a depreciation in the value of the euro.

(1 EUR = … national currency)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a), European Central Bank (ECB)

Figure 1a shows the development of the euro against the (British) pound sterling (GBP), the Swiss franc (CHF), and the United States dollar (USD).

Overall, the euro appreciated 5.0% against the pound sterling over the period 2014 to 2024. This change reflected falls in the value of the euro in 2015, 2019, 2021, 2022 and 2024, which collectively had a lower impact than the increases in the value of the euro in the other years. There was a particularly volatile period in 2015 and 2016, with a large depreciation of the euro against the pound sterling in 2015 (down 10.0%) followed by a large appreciation in 2016 (up 12.9%).

The euro depreciated 21.6% against the Swiss franc between 2014 and 2024. The euro fell steeply in 2015 (down 12.1%). Despite modest appreciations in the value of the euro in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2021, further falls in 2019, 2020 and 2022 to 2024 also contributed to its overall depreciation during the period under consideration.

The euro depreciated 18.5% against the United States dollar between 2014 and 2024. The euro depreciated sharply in 2015 (down 16.5%). Thereafter, developments were irregular, with the euro appreciating in 2017, 2018, 2020, 2021 and 2023, but depreciating in 2019 and notably in 2022 (down 11.0%); there was almost no change in 2024, as the euro depreciated marginally (down 0.1%).

(1 EUR = … national currency)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a), European Central Bank (ECB)

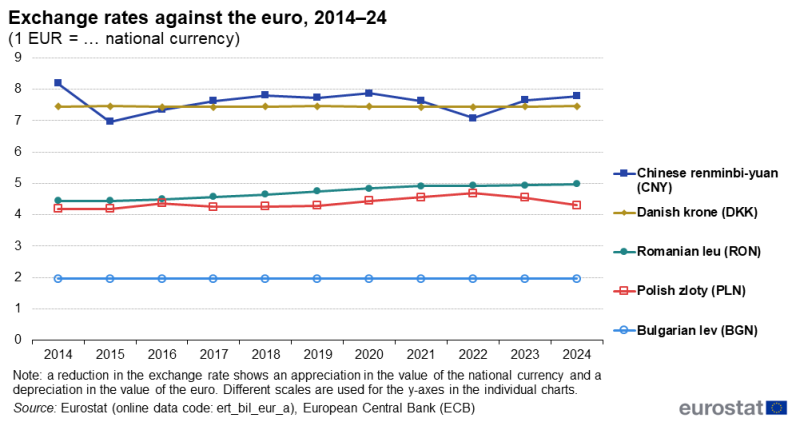

Figure 1b shows the development of the euro against the Bulgarian lev (BGN), the Polish zloty (PLN), the Romanian leu (RON), the Danish krone (DKK) and the Chinese renminbi-yuan (CNY).

The exchange rate between the euro and the Bulgarian lev was unchanged during the period under consideration as the lev has been pegged to the euro since its launch in 1999.

Between 2014 and 2024, the euro appreciated somewhat against the Polish zloty, up 2.9%. During the period under consideration, the euro was stable or appreciated against the zloty in all years except 2017 (down 2.4%), 2023 (down 3.1%) and 2024 (down 5.2%).

The euro appreciated strongly against the Romanian leu, up 11.9% between 2014 and 2024. The euro was stable or appreciated against the leu in all years.

Since 1 January 1999, Denmark has been a member of the ERM II. Its currency, the Danish krone, has been pegged to the euro with a band allowing fluctuations of +/- 2.25%. Over the period 2014 to 2024, there were only minor changes in this exchange rate, with annual decreases or increases of the euro in the range of -0.2% to +0.2%. Overall, the euro appreciated 0.1% against the Danish krone.

The euro depreciated 4.9% against the Chinese renminbi-yuan between 2014 and 2024. The euro depreciated strongly against the renminbi-yuan in 2015 (down 14.8%) and 2022 (down 7.2%) and more moderately in 2019 and 2021. In all other years, the euro appreciated against the Chinese renminbi-yuan.

(1 EUR = … national currency)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a), European Central Bank (ECB)

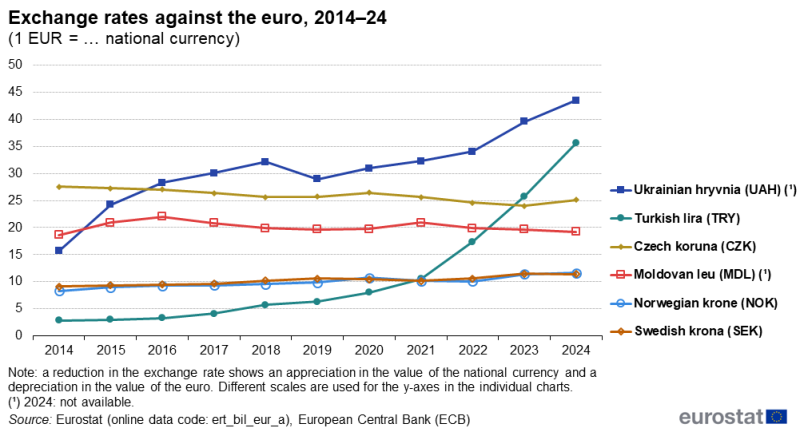

Figure 1c shows the development of the euro against the Swedish krona (SEK), the Norwegian krone (NOK), the Moldovan leu (MDL), the Czech koruna (CZK), the Turkish lira (TRY) and the Ukrainian hryvnia (UAH).

The euro appreciated 25.7% against the Swedish krona between 2014 and 2024. This reflected appreciation during all years except for 2020, 2021 and 2024; the strongest appreciation was in 2023, up 8.0%.

The euro appreciated 39.2% against the Norwegian krone between 2014 and 2024. The euro’s developments against the Norwegian krone followed a general upward trend, interrupted over 2 years: the euro was stable or appreciated each year between 2014 and 2020; it depreciated in 2021 and again in 2022 before appreciating strongly (up 13.1%) in 2023 and then at a more modest pace in 2024 (up 1.8%).

The euro appreciated 3.3% against the Moldovan leu over the period 2014 to 2024. This reflected relatively volatile movements. The euro appreciated in 2015 and 2016 (increasing by 12.1% and 5.6%, respectively). Some of this appreciation was lost in the following 3 years (2017 to 2019) before the euro appreciated again in 2020 and 2021. The development again reversed, with the euro depreciating against the leu in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

The euro depreciated 8.8% against the Czech koruna between 2014 and 2024. The exchange rate fluctuated between 2014 and 2021 by no more than +/- 3.1%. A larger appreciation (up 4.6%) was observed in 2024 while a larger depreciation (down 4.2%) was recorded in 2022.

Overall, the euro appreciated 1 123.9% against the Turkish lira. There was a regular appreciation of the euro against the Turkish lira, with the euro appreciating every year between 2014 and 2024. For example, in the 3 most recent years the euro appreciated by 65.6% (2022), 48.0% (2023) and 38.1% (2024).

The euro appreciated 177.2% against the Ukrainian hryvnia between 2014 and 2024. During this period, the euro appreciated against the hryvnia every year except for 2019 (down 10.0%). The euro appreciated most strongly in 2015 (up 54.2%). The 16.2% appreciation in 2023 and the 9.9% appreciation in 2024 were the two largest increases since 2016.

(1 EUR = … national currency)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a), European Central Bank (ECB)

Figure 1d shows the development of the euro against the Macedonian denar (MKD), the Albanian lek (ALL), the Serbian dinar (RSD), the Icelandic króna (ISK), the Japanese yen (JPY) and the Hungarian forint (HUF).

During this period, there was little movement in the exchange rate between the euro and the Macedonian denar with an overall depreciation of the euro of 0.2%. The Macedonian denar has been pegged (within a band of +/- 1% of a central rate) against the euro since 2002.

Between 2014 and 2024, a depreciation of the euro was observed against the Albanian lek (down 28.0% overall). The euro depreciated most years, with a slight appreciation in 2020. The largest depreciations were observed in 2023 and 2024, down 8.6% and 7.4%, respectively.

Overall, the euro depreciated marginally (down 0.2%) against the Serbian dinar between 2014 and 2024. Developments of the euro’s exchange rate against the Serbian dinar followed 3 stages: the euro appreciated between 2014 and 2016; the euro depreciated in 2017 and 2018; the euro depreciated slightly (down at most 0.4%) or was stable in the years from 2019 to 2024.

Over the period 2014 to 2024, the euro depreciated 3.6% against the Icelandic króna. This reflected depreciations in 2 periods, from 2014 to 2017 as well as in 2021 and 2022. Between these periods (in 2018, 2019 and 2020) the euro appreciated as it did again in 2023 (up 4.8%); it appreciated marginally (up 0.1%) in 2024.

The euro appreciated by 16.8% against the Japanese yen between 2014 and 2024. The exchange rate fluctuated in the early part of this period, with depreciations of the euro in 2015 and 2016, appreciations in 2017 and 2018, and depreciations in 2019 and 2020. In the 4 most recent years, there have been appreciations. The largest appreciations of the euro during this period were recorded in 2023 (up 10.1%) and 2024 (up 7.8%).

Among the national currencies of non-euro area EU countries, the euro appreciated between 2014 and 2024 most strongly against the Hungarian forint (up 28.0%). This overall appreciation was accumulated over most of the period, as the euro appreciated against the forint every year apart from 2017 (when it depreciated slightly, down 0.7%) and 2023 (when it depreciated more strongly, down 2.4%).

Interest rates

EU (weighted) average bond yields (see the explanatory notes for more information) were higher in 2024 than they had been in 2019 (see Figure 2). In the EU, bond yields in 2024 (3.26%) were 2.54 percentage points higher than they had been in 2019 (0.72%). The change for the euro area was somewhat smaller, as bond yields in 2019 (0.44%) were 2.48 percentage points lower than in 2024 (2.92%). In relative terms, bond yields in the EU were 4.5 times as high in 2024 as in 2019, while the corresponding ratio for the euro area was 6.6 times as high.

Between 2019 and 2024, yields increased in all EU countries for which data are available (no 2019 data are available for Estonia). Bond yields increased between 2019 and 2024, most notably in Hungary (up 4.03 percentage points). In most of the remaining EU countries for which data are available, the yields increased in the range of 1.76 to 3.50 percentage points, with Greece (up 0.76 percentage points) below this range. Note that Greece had the 2nd highest yields in 2019 among the EU countries, reflecting in part the impact of the global financial and economic crisis and subsequent sovereign debt crisis.

Hungary (6.50%), Romania (6.32%) and Poland (5.53%) were the only EU countries with bond yields that were above 5.00% in 2024. A total of 12 EU countries had yields below 3.00%, among which Sweden (2.20%), Denmark (2.30%) and Germany (2.32%) had the lowest yields.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (irt_lt_mcby_a)

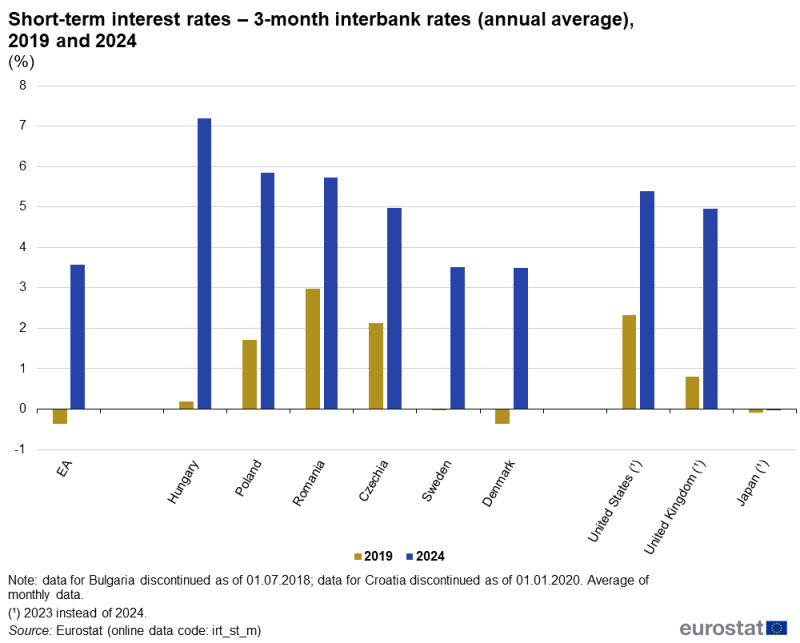

Figure 3 shows 3-month interbank rates (see the explanatory notes for more information). Money market rates, also known as interbank rates, are interest rates used by banks for operations among themselves. In the money market, banks are able to borrow and re-lend highly liquid assets between themselves. The SOFIBOR, the interbank rate in Bulgaria, was discontinued as of 1 July 2018 and therefore no data were compiled for either period shown in the figure (2019 or 2024).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (irt_st_m)

In the euro area, the interbank rate rose from -0.36% in 2019 to 3.57% in 2024. Interbank rates were higher in 2024 than in 2019 for all non-euro area countries for which data are available. As in the euro area, Denmark and Sweden also reported negative rates in 2019 and relatively low positive rates in 2024. In absolute terms, the largest percentage point increases between 2019 and 2024 among the non-euro area countries was in Hungary, up 7.00 percentage points from 0.19% in 2019 to 7.19% in 2024. Elsewhere, the increases ranged from 2.76 percentage points in Romania to 4.14 percentage points in Poland.

For comparison, the annual average of 3-month interbank rate of the United Kingdom rose 4.15 percentage points between 2019 and 2023, while in the United States the increase was 3.06 percentage points during the same period. In Japan, interbank rates remained stable and just under zero, increasing 0.06 percentage points between 2019 and 2023.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (irt_euryld_a), European Central Bank (ECB)

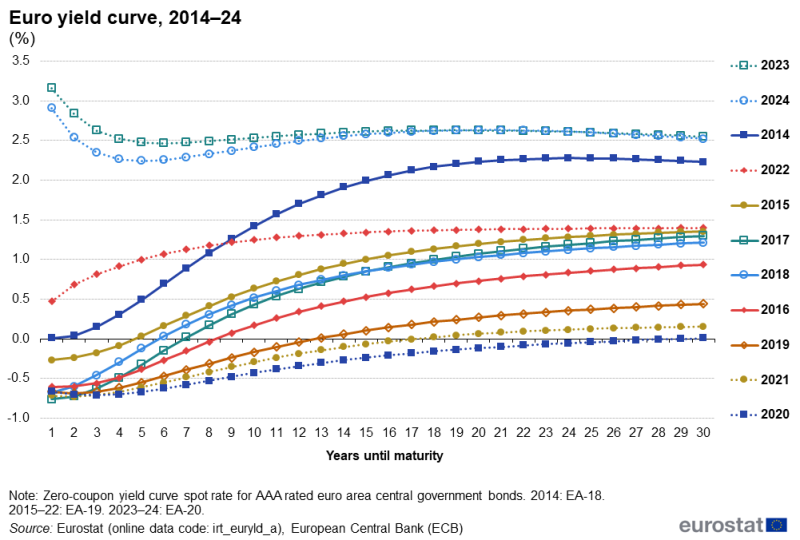

Figure 4 shows the euro yield curve between 2014 and 2024 for central government bonds with various years remaining to maturity.

- Yields were relatively high just before the onset of the financial and economic crisis in 2008 but fell thereafter. Bond yields for almost all maturities fell most years through to a low in 2016 before increasing somewhat in 2017 and stabilising in 2018.

- In 2019 and again in 2020, yields were once more at historic lows for almost all maturities, the only exceptions being for 1 or 2 years to maturity. In 2020, bonds with 29 or fewer years to maturity had negative yields while bonds with 30 years to maturity offered a yield of just 0.01%.

- This trend shifted rapidly in 2021: bonds with 17 or fewer years to maturity had negative yields while bonds with 30 years to maturity offered a yield of 0.15%.

- This development continued in 2022, as positive yields were observed for bonds for all maturities (up to 30 years). The yield for bonds with 30 years to maturity was 1.40%, the highest yield for a bond with 30 years to maturity since 2014.

- In 2023, positive yields were again observed for bonds for all maturities (up to 30 years), with yields higher than in 2022 for all maturities. In fact, the yields in 2023 were higher than those observed in any of the older years presented in Figure 4.

- In 2024, positive yields were observed for the 3rd consecutive year for bonds for all maturities (up to 30 years). Yields in 2024 were generally lower than those in 2023; the exceptions were for bonds with 20 to 24 years to maturity, which had marginally higher yields in 2024.

- Unlike in most other years, the highest yields observed in 2024 were for bonds with the shortest maturity, 2.91% for bonds with 1 year to maturity.

- The rates were quite similar, ranging between 2.52% and 2.63%, for bonds with 2 years to maturity and for those with a longer maturity (at least 13 years and up to 30 years).

- The yields were below 2.50% for bonds with 3 to 12 years to maturity; the lowest yield was 2.24% for bonds with 5 years to maturity.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Exchange rates

Eurostat publishes a number of different datasets concerning exchange rates. There are 2 main datasets, with statistics on

- bilateral exchange rates between currencies, including some special conversion factors for countries that have adopted the euro

- effective exchange rate indices.

Bilateral exchange rates are available with reference to the euro, although before 1999 they were given in relation to the European currency unit (ECU). The ECU ceased to exist on 1 January 1999 when it was replaced by the euro at an exchange rate of 1:1. From that date, the currencies of the euro area became subdivisions of the euro at irrevocably fixed rates of conversion.

Daily exchange rates are available from 1974 onwards against a large number of currencies. These daily values are used to construct monthly and annual averages, which are based on business day rates; alternatively, month-end and year-end rates are also published. From 2010 onwards the official rate for the Icelandic króna (ISK) is shown for indicative purposes.

Interest rates

Interest rates provide information on the cost or price of borrowing, or the gain from lending. Traditionally, interest rates are expressed in annual percentage terms, although the period for lending/borrowing can be anything from overnight to a period of many years. Different types of interest rates are distinguished either by the period of lending/borrowing involved, or by the parties involved in the transaction (business, consumers, governments or interbank operations).

Long-term interest rates are 1 of the convergence criteria for European economic and monetary union (EMU). In order to comply, EU countries need to demonstrate an average nominal long-term interest rate that doesn’t exceed by more than 2 percentage points that of, at most, the 3 best-performing EU countries. Long-term interest rates are based upon central government bond yields (or comparable securities), taking into account differences in national definitions, on the secondary market, gross of tax, with a residual maturity of around 10 years.

Eurostat also publishes a number of short-term interest rates, with different maturities (overnight, 1 to 12 months). A yield curve, also known as the term structure of interest rates, represents the relationship between market remuneration (interest) rates and the remaining time to maturity of government bonds.

Context

Interest rates, inflation rates and exchange rates are highly linked: the interaction between these economic phenomena is often complicated by a range of additional factors such as levels of government debt, the sentiment of financial markets, terms of trade, political stability and overall economic performance.

An exchange rate is the price or value of a currency in relation to another. Those countries with relatively stable and low inflation rates tend to display an appreciation in their currencies, as their purchasing power increases relative to other currencies, whereas higher inflation typically leads to a depreciation of the local currency. When the value of a currency appreciates against another, then that country’s exports become more expensive and its imports become cheaper.

Through using a common currency, the countries of the euro area have removed bilateral exchange rates and, therefore, aim to benefit from the elimination of currency exchange costs, lower transaction costs and the promotion of trade and investment resulting from the scale of the euro area market. Furthermore, the use of a single currency increases price transparency for consumers across the euro area.

All economic and monetary union participants are eligible to adopt the euro. Aside from demonstrating 2 years of exchange rate stability (via membership of ERM II), those EU countries aiming to join the euro area also need to adhere to a number of additional criteria relating to interest rates, budget deficits, inflation rates and debt-to-GDP ratios.

From 1 January 2002, euro notes and coins entered circulation in the euro area, as 12 EU countries – Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal and Finland – adopted the euro as their common currency. Slovenia subsequently joined the euro area at the start of 2007 and was followed by Cyprus and Malta on 1 January 2008, Slovakia on 1 January 2009, Estonia on 1 January 2011, Latvia on 1 January 2014, Lithuania on 1 January 2015 and Croatia on 1 January 2023, bringing the total number of countries using the euro as their common currency to 20.

Central banks seek to exert influence over both inflation and exchange rates by way of monetary policy. Their main tool for this purpose is the setting of key interest rates. In joining the euro, each EU country agrees to allow the European Central Bank (ECB) to act as an independent authority responsible for maintaining price stability through the implementation of monetary policy. As of 1999, the ECB started to set benchmark interest rates and manage the euro area’s foreign exchange reserves. The ECB has defined price stability as a year-on-year increase in the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) for the euro area below, but close to, 2% over the medium term (see the article on consumer prices – inflation and comparative price levels). Monetary policy decisions are taken by the ECB’s governing council that meets every 6 weeks to analyse and assess economic and monetary developments and the risks to price stability and thereafter to decide upon the appropriate level of key interest rates.

Explore further

Database

- Exchange rates (ert)

- Bilateral exchange rates (ert_bil)

- Effective exchange rate indices (ert_eff)

- Exchange rates - historical data (ert_h)

- Interest rates (irt)

- Euro yield curves (irt_euryld)

- Long-term interest rates (irt_lt)

- Short-term interest rates (irt_st)

- Interest rates - historical data (irt_h)

Thematic section

Selected datasets

- Exchange rates (t_ert)

- ECU/EUR exchange rates versus national currencies (tec00033)

- Euro/national currency exchange rates (teimf200)

- Real effective exchange rate - 42 trading partners (teimf250)

- Interest rates (t_irt)

- Euro yield curve by maturity (1, 5 and 10 years) (teimf060)

- EMU convergence criterion series - annual data (tec00097)

- Long term government bond yields (teimf050)

- Day-to-day money market interest rates (teimf100)

- 3-month-interest rate (teimf040)

Methodology

- Euro/ECU exchange rates (ESMS metadata file – ert_bil_eur_esms)

- Conversion factors for euro fixed series into euro/ECU (ESMS metadata file – ert_bil_conv_esms)

- Effective exchange rate indices (ESMS metadata file – ert_eff_esms)

- Euro yield curves (ESMS metadata file – irt_euryld_esms)

- Government bond yields - 10 years' maturity (ESMS metadata file – irt_lt_gby10_esms)

- Maastricht criterion interest rates (ESMS metadata file – irt_lt_mcby_esms)

- Short-term interest rates (ESMS metadata file – irt_st_esms)

External links

Central banks within the European Union

- European Central Bank

- Belgium: Nationale Bank van België / Banque nationale de Belgique

- Bulgaria: Българската народна банка

- Czechia: Česká národní banka

- Denmark: Danmarks Nationalbank

- Germany: Deutsche Bundesbank

- Estonia: Eesti Pank

- Ireland: Banc Ceannais na hÉireann / Central Bank of Ireland

- Greece: Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος

- Spain: Banco de España

- France: Banque de France

- Croatia: Hrvatska narodna banka

- Italy: Banca d’Italia

- Cyprus: Kεντρική Τπάπεζα της Κύπρου

- Latvia: Latvijas Banka

- Lithuania: Lietuvos bankas

- Luxembourg: Banque Centrale du Luxembourg

- Hungary: Magyar Nemzeti Bank

- Malta: Bank Ċentrali ta’ Malta/Central Bank of Malta

- Netherlands: De Nederlandsche Bank

- Austria: Österreichische Nationalbank

- Poland: Narodowy Bank Polski

- Portugal: Banco de Portugal

- Romania: Banca Naţională a României

- Slovenia: Banka Slovenije

- Slovakia: Národná banka Slovenska

- Finland: Suomen Pankki/Finlands Bank

- Sweden: Sveriges Riksbank

Selected central banks outside the EU

- China: Bank of China

- Japan: Bank of Japan

- United Kingdom: Bank of England

- United States Federal Reserve

Bank for International Settlements

Legislation

- Regulation (EC) No 2866/98 of 31 December 1998 on the conversion rates between the euro and the currencies of the EU countries adopting the euro

- Summaries of EU Legislation: Conversion rates between national currencies and the euro