Inland transport infrastructure at regional level

Data extracted in June 2024.

Planned article update: June 2025.

Highlights

Between 2012 and 2022, three Spanish, one Slovakian and two Romanian regions had the largest expansion of motorways in the EU.

In 2022, nearly the entire rail network of Luxembourg was electrified; the lowest electrification was registered in the Baltic States and Ireland.

In 2022, the highest motorway densities were found in regions of Germany and the Netherlands as well as in the capital regions of Hungary and Austria.

- Motorway density, by regions, 2022 (km of motorways per 1 000 km²)

- Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net)

- Motorway density, by regions, 2022 (km of motorways per 1 000 km²)

This article presents recent data on the inland transport network of the European Union (EU), EFTA and candidate countries: motorways, railways and inland waterways. The evolution of the transport network is closely linked to the general development of the economy. This is particularly true for goods transport and, to a lesser extent, for passenger transport.

Full article

The densest motorway networks are located around capitals and key economic hubs

The EU has one of the densest transport networks in the world. This reflects a number of factors, including population density and transport demand. Transport demand is particularly high in urban and other densely populated areas, industrial areas and main seaports. In 2022, the highest motorway densities were found in regions of Germany and the Netherlands as well as in the capital region of Hungary and Austria (see Table 1).

(km of motorways per 1 000 km2)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net)

Linking the length of motorways to the area of the regions gives a good picture of the motorway infrastructure and density within the EU (see Map 1). The highest motorway densities are found around European capitals and other big cities, in large industrial conurbations and around major seaports.

Most European capitals and large cities are surrounded by a ring of motorways in order to meet the high demand for road transport in metropolitan areas. In 2022, dense motorway networks could be found in regions around capitals: Budapest (120 km/1 000 km2), Wien (109 km/1 000 km2), Madrid (92 km/1 000 km2), Berlin (86 km/1 000 km2) and Praha (81 km/1 000 km2). Region sizes vary across the EU with some capitals being designated as NUTS 2 regions themselves, such as Wien, whereas other capitals are parts of a larger NUTS 2 region, such as Paris being part of the Île-de-France region. As a consequence, small capital regions might have higher motorway densities compared with larger regions that include a capital. For example, the motorway density of the small Wien region is higher than the density of the large Île-de-France region, even though Paris has a larger motorway network than Wien. In 2022, other densely populated regions with high motorway density included the Randstad area (an arc-shaped conurbation including the Netherlands' four largest cities and their suburbs) in the western part of the Netherlands (Utrecht: 132 km/1 000 km2 and Zuid-Holland: 125 km/1 000 km2), which is of high economic importance.

High motorway densities were also found around major seaports of northern Europe: the motorway densities of the NUTS 2 regions of Bremen (169 km/1 000 km2) with the port of Bremerhaven, of Zuid-Holland with the port of Rotterdam (125 km/1 000 km2) and of Hamburg (104 km/1 000 km2) were among the highest of all European regions.

Another reason for the high density of the motorway network in some central Europe countries (such as Germany) is the proportionately high volume of transit freight traffic. The density of motorways on islands is generally low, as islands cannot be reached directly by road. Instead, they rely on sea or air transport. Even so, the motorway density of the region of Canarias appeared relatively high at 38 km/1 000 km2 in 2022 (provisional data).

(km of motorways per 1 000 km2)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net)

In terms of motorway expansion, between 2012 and 2022 the most significant expansion took place in certain regions of Spain: extensive motorway segments (between 162 and 271 kilometers) were built in the south and north of Spain, reflecting still the results of Spain's ambitious road building programme that started in the 1990s. Slovakian, Romanian, Czech, Polish and Bulgarian regions also show significant network expansions (see Figure 1).

(km of motorways)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net)

In more detail, the most significant motorway expansion between 2012 and 2022 took place in the Turkish region of Istanbul (357 km). This was followed by two Spanish regions: Andalucia in the south (271 km) and Castilla y León in the northwest (242 km). Cataluña (171 km) and Galicia (162 km) also appeared in the top 15 for motorway expansion (see Figure 1). The noticeable increases in many regions of eastern EU Member States (notably Slovakia, Romania, Czechia, Poland) could be explained by the very limited motorway networks in these regions at the beginning of the century and the considerable investments that followed, often (co-)financed by the European Regional Development Fund and Cohesion Fund. Apart from the aforementioned region of Istanbul, the candidate country Türkiye was listed in the top 15 with four other regions, with expansions ranging between 165 km (Ankara) and 194 km (Kocaeli, Sakarya, Düzce, Bolu, Yalova).

Highest railway line density often in capital regions and around transport hubs

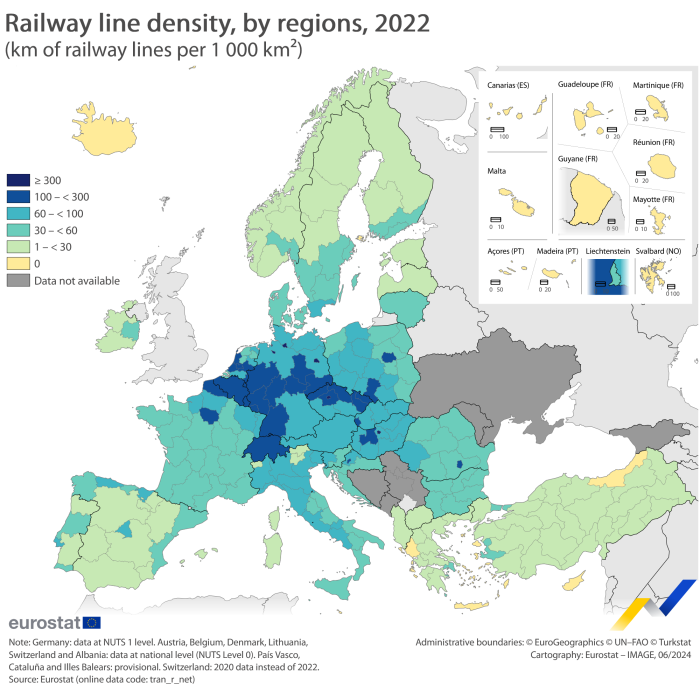

Railway line density is especially high in the regions of Belgium, Germany, Czechia, Hungary, the Netherlands and Poland (see Map 2). Unsurprisingly, the highest rail density ratios were observed in capital regions, such as Berlin, Budapest, Praha, Île-de-France (which includes Paris), and Bucuresti-Ilfov where network nodes have developed. Regional rail density is also driven by the presence of economic activities such as heavy industries or seaport infrastructures.

In 2022, the density of railway lines was high in western and central parts of Europe and lower in the peripheral areas. The highest network densities, above 300 km/1 000 km2, could be found in three regions in Germany, one in Hungary and one in Czechia, followed by 27 other EU regions in Czechia, Poland, Germany, Romania, France, Croatia, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Luxembourg and Hungary (above 100 km/1 000 km2).

Looking at individual regions, the densest railway networks in 2022 were observed in two German regions: Berlin (760 km/1 000 km2) and Hamburg (641 km/1 000 km2). These regions were followed by Budapest (502 km/1 000 km2), Praha (437 km/1 000 km2) and Bremen (386 km/1 000 km2). Hamburg and Bremen are two smaller NUTS 2 regions where extensive freight lines to and from seaports contribute to a high density.

Freight transport railway lines also played a leading role in several regions where coal and steel industries have long remained predominant, such as the Saarland region in western Germany (136 km/1 000 km2 and Śląskie in southern Poland (154 km/1 000 km2).

(km of railway lines per 1 000 km2)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net)

Focusing on railway infrastructure at country level, there are significant differences among countries with respect to the share of the network that were electrified in 2022. Luxembourg (97 %), Belgium (88 %), Sweden and Bulgaria (75 %), the Netherlands (74 %), Italy (73 %), Austria (72 %) and Portugal (71 %) registered the highest shares, while Ireland, and the Baltic States were the only EU Member States where less than 20 % of the network was electrified in 2022.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net)

Very high density of inland waterways in the Netherlands

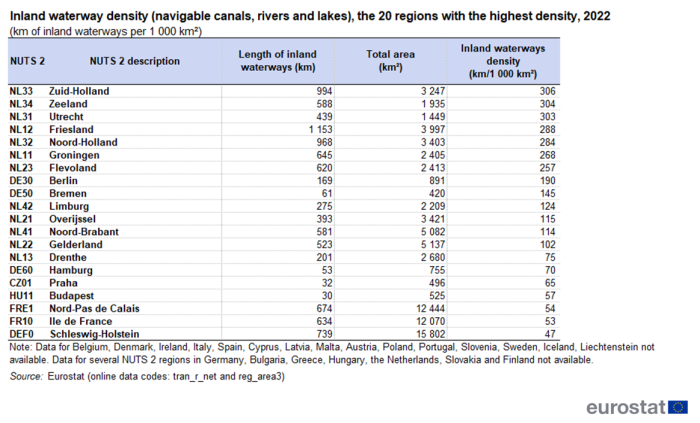

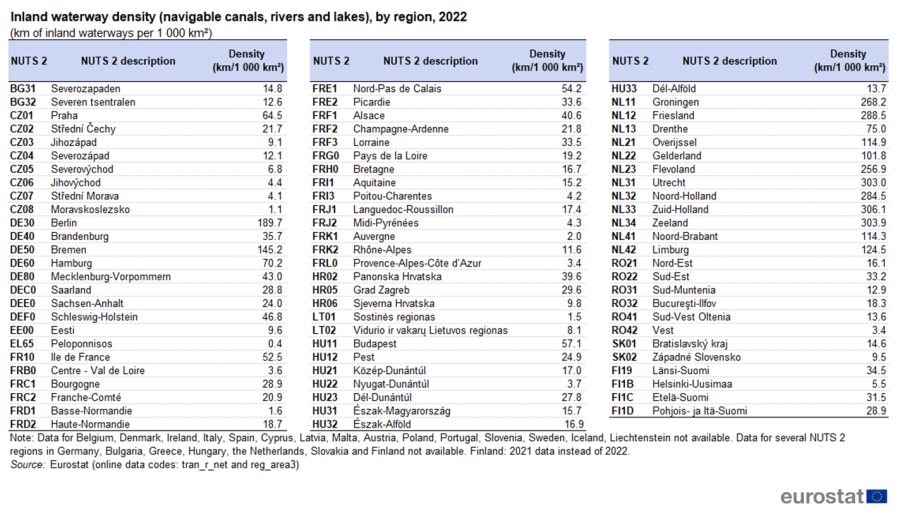

Inland waterway transport concerns mainly goods transport. This network is unequally spread over the EU, with some regions completely lacking navigable inland waterways and others having a very long waterway system, such as the regions of the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, while the Rhine delta constitutes a natural feature for inland navigation, for most regions man-made canals constitute the main share of navigable inland waterways.

A very high density of more than 200 km/1 000 km2 was observed in seven regions of the Netherlands: Zuid-Holland (306 km/1 000 km2), Zeeland (304 km/1 000 km2), Utrecht (303 km/1 000 km2), Friesland (288 km/1 000 km2), Noord-Holland (284 km/1 000 km2), Groningen (268 km/1 000 km2) and Flevoland (257 km/1 000 km2) (see Table 2). The lowest density in the Netherlands was registered in the Drenthe region (75 km/1 000 km2), which still ranked 14th amongst all regions for which data were available. A part of this dense inland waterway network plays a strategic role for freight transport between both the ports of Rotterdam (located in the Zuid-Holland region) and Amsterdam (Noord-Holland) and regions in Germany and Belgium.

(km of inland waterways per 1 000 km2)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net) and (reg_area3)

Four of the top 20 regions with the highest density belonged to Germany: Berlin (190 km/1 000 km2 - essentially composed of canals), Bremen (145 km/1 000 km2 - entirely composed of rivers), Hamburg (70 km/1 000 km2 - essentially composed of rivers), and Schleswig-Holstein (47 km/1 000 km2).

Other regions with a dense inland waterway network were found in Czechia (Praha: 65 km/1 000 km2), Hungary (Budapest: 57 km/1 000 km2, and France (Nord-Pas-de-Calais: 54 km/1 000 km2, Île de France: 53 km/1 000 km2). The network in most French regions is a mix between rivers and canals, except for Champagne-Ardenne, Picardie, Haute-Normandie, Basse-Normandie, Centre (FR), Midi-Pyrénées, Auvergne and Lorraine where canals take a 100 % share, in contrast to Poitou-Charentes where the inland waterways are entirely composed of rivers.

(km of inland waterways per 1 000 km2)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_net) and (reg_area3)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Eurostat collects regional statistics on the infrastructure of road, railways and inland waterways, as well as vehicle stocks and road accidents. The data are provided on a voluntary basis by the EU Member States, EFTA countries and some candidate countries. The data are collected at NUTS 0, NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 levels.

Density calculation : the reference area for the calculation of motorway and railway line density is the land area of the regions (e.g. excluding lakes and rivers): this is the area where such infrastructure can be built; the reference area for the calculation of inland waterway density is the total area of the regions (e.g. area including lakes and rivers).

Rankings in figures and tables: as the data collection is performed on a voluntary basis, data are not available for some countries; consequently, the rankings presented are based on the available data and they should be analysed with caution.

Country coverage:

- Motorways: 2022 data on the length of the motorway network are not available for Greece and Finland. In certain cases, 2020 data have been used, as mentioned in the footnotes. A certain number of countries do not feature a motorway network: Malta, Latvia, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

- Railways: 2022 data on the length of the railway network are not available for Switzerland. In certain cases, 2020 data have been used instead, as mentioned in the footnotes. A certain number of countries do not feature a rail network: Cyprus, Malta and Iceland.

- Inland waterways: 2022 data on the length of the network (navigable rivers and lakes, navigable canals) is not available for: Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Cyprus, Latvia, Malta, Austria, Portugal, Slovenia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Data for several NUTS 2 regions in Germany, Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, the Netherlands, Slovakia and Finland are not available. Data for NUTS2 region in Austria, Poland and Sweden are not available. Most countries do not have navigable inland waterways at all; others may have a network, but it does not meet the minimum requirements in terms of minimum carrying capacity according to the 1992 UNECE/ECMT Classification of European Inland Waterways, canals, navigable rivers.

- Data for the candidate countries have been compiled on the basis of available data.

- Available data from 2020 and 2021 have been used if 2022 data were not.

Country-specific notes:

- Estonia: data on motorways refer to 1st class roads.

- Italy: data for motorways and railway lines declared for Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano/Bozen (ITH1) include the network for the Provincia Autonoma di Trento (ITH2). For the purpose of the maps, the total area of the two regions has been considered and the density figures have been equally spread between these two regions.

- Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia has reported transport infrastructure data. The network density indicators could however not be calculated as the area information (land area for motorways and rail, total area for inland waterways) was not available at the time of publishing.

- Ireland: reported data for inland waterways include unnavigable river, canals and lakes, therefore Ireland is excluded from the analysis.

Regional breakdown

The Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) was established by Eurostat around 50 years ago in order to provide a single uniform breakdown of territorial units for the production of regional statistics for the Community. Since then, it has been updated regularly. Five smaller EU Member States (Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Luxembourg and Malta) are not sub-divided into NUTS regions. Very similar to the EU-specific NUTS classification, a statistical regions breakdown also exists for the EFTA countries and the candidate countries. Here too, the smaller countries Liechtenstein, Iceland and North Macedonia are not sub-divided into regions.

Context

Efficient transport services and infrastructure are vital to exploiting the economic strengths of all regions of the European Union, to supporting the internal market and growth, and enabling economic and social cohesion. They also influence trade competitiveness, as the availability, price, and quality of transport services have strong implications on production processes and the choice of trading partners.

Transport investments enable economic growth and job creation. Investing in transport infrastructure, particularly in railways and inland waterway navigation, also contributes to the decarbonisation of transport. The sector currently accounts for almost a quarter of the EU's greenhouse gas emissions, of which 70 % comes from road transport in 2019 (see: Transport emissions).

Transport, however, faces a wide range of challenges across the EU: underinvestment, lack of suitable financing solutions, continuous growth of urban populations, and various regulatory and administrative barriers. The European Commission is addressing these issues, paving the way for the competitive and sustainable EU transport system of tomorrow. The Strategy for Sustainable and Smart Mobility sets the actions needed in each transport mode for delivering on the European Green Deal, enabling in this way smoother connectivity and a more resilient Single European Transport Area. Efficient connectivity for all EU citizens is a critical aspect of social inclusion and an important determinant of well-being. It stimulates economic growth, territorial cohesion and helps reduce our impact to the environment. Transport is the only economic sector in which greenhouse gas emissions are higher than in 1990, despite the mitigation efforts undertaken. The European Green Deal has therefore set the key objective to deliver a 90 % reduction in transport-related greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Building missing links at borders between EU Member States and along key European routes, as well as removing bottlenecks or interconnecting transport modes in terminals, is vital for the Single Market and for connecting Europe with external markets and trade partners. The smooth functioning of the European network requires integration and interconnection of all modes of transport.

The adaptation of infrastructure to new mobility patterns and the deployment of infrastructure for clean energy sources pose additional challenges that require new investments and a different approach to the design of networks.

Direct access to

Other articles

Publications

Database

- Transport, see:

- Area, see:

Dedicated section

Data visualisations

- Regional Statistics Illustrated - select statistical domain 'Transport' (top right)