Data extracted in June 2025.

Planned article update: June 2026.

Highlights

EU imports and exports of goods and services, 2012-2024

This article describes the construction of a set of European Union (EU) economic globalisation indicators. It presents results for the selected indicators, illustrating the type of information which could be used to track different aspects of globalisation. The article also explains the methodological issues of developing globalisation indicators and presents detailed information about the data sources and data breakdowns available.

The economic globalisation indicators are displayed in Eurostat's Globalisation Dashboard (24 indicators) and in the dedicated section on globalisation of businesses (additional 3 indicators). These indicators present EU citizens, policymakers and businesses with trends in business dynamics and characteristics, international trade and investments in an easily accessible format. The interactive dashboard shows the EU's role in globalisation within 3 main topics:

- Global value chains;

- Global trading partnerships;

- Global investments.

The dashboard is updated automatically when new or revised data become available in Eurostat's database, thus always showing the most up-to-date picture.

Overview

The results show that:

- Employment shares in foreign-controlled enterprises in 2022 are generally lower compared with 2020 in the largest EU economies.

- There was an increase in the number of persons employed in multinational enterprise groups (MNE groups) in 2023 as recorded in the EuroGroups register. However, the share of the persons working in MNE groups in the total employment in Europe is stable.

- A declining trend in EU enterprises sourcing abroad was exhibited, from the peak of 11.7% (2002-2006) to the lowest share of 2.7% (2018-2020).

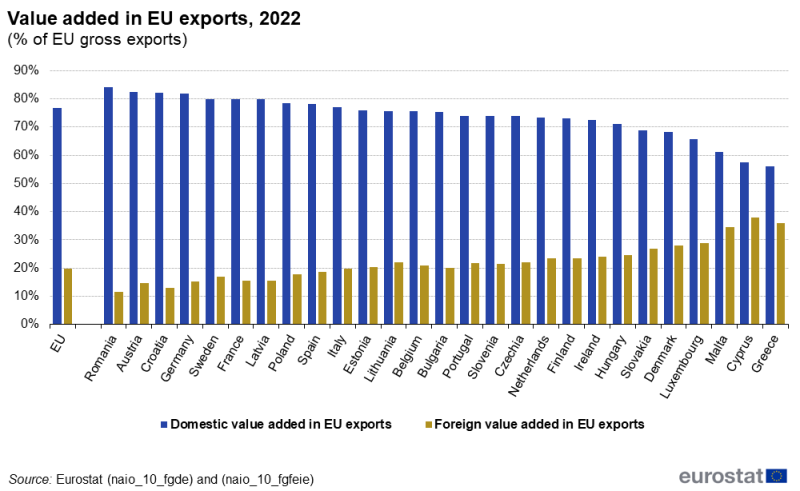

- The highest share of foreign value-added supported by EU exports in 2022 was observed in small, open EU economies.

- A declining trend in greenhouse gas emissions was observed in the EU from both consumption (footprint) and production perspectives in the period 2012-2023.

- The EU export-to-import ratio rebounded in 2024 after experiencing a slight drop in 2022 and it remains positive, indicating a consistent trend of the EU countries exporting slightly more than importing.

- The proportion of both trade in intermediate goods as a share of total goods trade and trade in intermediate services as a share of total services had an upward trend in the period 2017-2022, with a slight drop until 2024.

- The share of the trade with the top 5 partner countries shows that the EU is much more reliant on a limited number of trading partners for trade in services than for trade in goods.

- The EU remains a net foreign direct investor in the world with a steady decline in the values of inward and outward FDI stocks as a percentage of GDP in the period 2017-2023.

- In the years 2020-2023, foreign investors investing in the EU generally had a higher return on their investments compared with investors in the EU investing abroad.

Global value chains

Employment

Employment plays a critical role in driving economic growth and prosperity, and it is influenced by various factors, including the presence of foreign-controlled enterprises, foreign affiliates, and multinational enterprise (MNE) groups. These entities contribute significantly to job creation and employment opportunities, particularly in the context of EU exports.

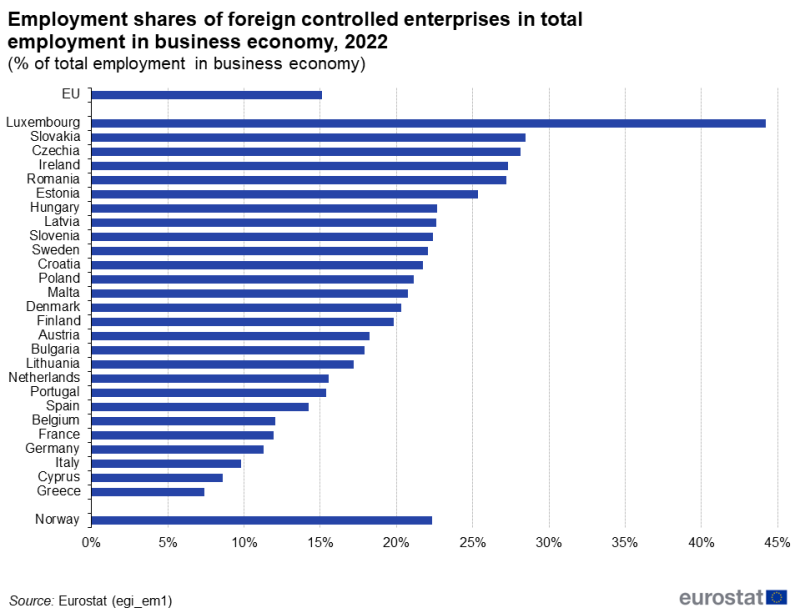

Employment in foreign-controlled enterprises in the EU significantly varies from one EU country to another. This variation is highlighted by different levels of foreign investment and the presence of foreign-controlled enterprises in domestic labour markets. Higher employment shares in foreign-controlled enterprises can contribute to job creation, knowledge transfer, and economic growth. At the same time, lower percentages may reflect a greater reliance on domestic enterprises (or domestically controlled multinational enterprise groups) and industries. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for policymakers and economic stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding economic strategies and labour market policies.

Figure 1 presents the percentages of employment shares of foreign-controlled enterprises, excluding the reporting country, in the total domestic employment in each EU country for the year 2022.

Source: Eurostat (egi_em1)

According to the EuroGroups Register (EGR), employment in MNE groups within the EU has increased over the past few years, reaching over 47.8 million persons in 2023 compared with 40.0 million in 2018. However, the share of persons working in MNE groups in the EU is relatively stable. Recent data highlight this stability, revealing a consistency in employment share figures: 31% in 2018 and 2019, 32% in 2020, a slight drop to 28% in 2021 and 2022, followed by an increase to 29% in 2023 (provisional data). In 2021, a break in the time series was recorded, caused by the extended scope of the NACE sections used for the total employment (i.e. the denominator). Since 2021, the total employment encompassed the employment in the NACE activity sections B to S (excluding O and S94), while before 2021, only the non-financial business economy was covered in this article (NACE sections from B to N, excluding K), although EGR itself has a wider coverage (no restriction on NACE).

Source: Eurostat (egr_emp)

The EU has long been considered a magnet for MNE groups, attracting businesses from around the world. The MNE groups capitalise on the EU's robust economy, highly skilled workforce, and strategic location, enabling them to establish a strong presence across multiple countries. The increase in employment in the MNE groups reflects the attraction of European enterprises for the MNE groups – MNE groups expand their control over more European enterprises – e.g. via restructuring events such as mergers or acquisitions. In addition, the EU is able to create an environment favourable to business growth and job creation. Finally, the employment in the MNE groups is highly concentrated - 4% of MNE groups employ 80% of the persons working for MNE groups in Europe.

Foreign affiliates play a significant role in shaping the EU's employment landscape. Data for 2022 highlight the diverse contributions of foreign affiliates across EU countries, with some countries experiencing higher employment shares than others. These figures illustrate the proportion of jobs supported by foreign affiliates abroad in relation to the domestic jobs in the reporting country. In 2022, Ireland and Denmark emerged as front-runners, boasting the highest share of employment in foreign affiliates at 37.2% and 36.0%, respectively. Conversely, Bulgaria and Romania reported the lowest shares, falling below 1%.

EU exports play a crucial role in driving economic prosperity by facilitating trade relationships and opening new markets for EU countries. Recent data reveal a consistent and steady contribution of EU exports to employment figures over the years, with percentages ranging from 14% to 15% between 2015 and 2022.

Finally, the employment opportunities generated by EU businesses facilitate the production and trade of goods and services for both domestic and international markets. As EU enterprises expand their operations and engage in cross-border trade, they contribute to economic interdependence and the integration of global value chains.

Enterprise activity

Within the EU, enterprises play a pivotal role in driving and shaping the process of globalisation. The exploration of the contributions of EU enterprises to globalisation highlights the significance of enterprises outsourcing and insourcing abroad, and the role of research and development within enterprises.

Foreign-controlled enterprises, enterprises that are part of MNE groups, and domestic enterprises often engage in international sourcing of business functions. This practice enables enterprises to tap into international expertise, achieve cost efficiency, and expand their market reach. Within the EU, the trend of enterprises sourcing business functions abroad has been observed over various periods, as reported in the Global Value Chains survey.

Figure 3 shows that over the years, there has been a significant decline in the reported share of enterprises sourcing abroad in different periods, from the highest reported share of enterprises sourcing abroad in the period 2002-2006 (11.7%) to the lowest share in the most recent period, 2018-2020 (2.7%)[1]. It is essential to recognise that the reported shares only reflect the number of new sourcing occurrences and do not account for past sourcing activities. Consequently, while the proportion of enterprises engaging in sourcing within a single period might appear low, the cumulative impact across all periods should not be underestimated.

The figures indicate a general downward trend in the percentage of enterprises sourcing business functions abroad across different periods. However, as noted earlier, international sourcing is a cumulative structural process, and many jobs, primarily in manufacturing or ICT, were already sourced abroad at the beginning of the century.

Value-added

Value-added supported by EU exports of goods and services acts as an important indicator of the role of exports in the process of globalisation. In 2022, there were significant variations across EU countries in terms of the contribution of exports to total value added. Cyprus stood out with the highest share, where EU exports accounted for 37.8% of its foreign value-added. Greece and Malta followed behind with 35.9% and 34.4% respectively. Conversely, Croatia and Romania had the lowest shares in 2022, with EU exports supporting 12.9% and 11.7% of their respective foreign value-added. On the other hand, EU exports accounted for 84.0% of domestic value added in Romania and 82.4% in Austria. In Cyprus (57.6%) and Greece (56.1%), EU exports accounted for the least domestic value added.

Countries with high shares point to strong integration into global markets, where exports drive economic growth and development. Countries with lower shares may have a more diversified economic base or face different challenges in exporting their goods and services.

In turn, the share of value-added in foreign-controlled enterprises as a part of the total value-added provides insights into the contribution of foreign investment to national economies. This data for 2022 reveals notable variations across EU countries. Ireland reported the highest share of value added in foreign-controlled enterprises, at 71.0%. On the other hand, Germany and France reported the lowest shares of value added in foreign-controlled enterprises in 2022, with 17.4% and 15.6%, respectively. These contrasting figures highlight the varying role of foreign-controlled enterprises and the resulting impact on value-added across EU countries.

Environmental impact of globalisation

Globalisation has significant environmental impacts, particularly in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. Figure 5 presents greenhouse gas emissions from 2 perspectives: production and consumption (commonly termed 'footprints'). The greenhouse gas emission footprints are related to the final consumption and investment of goods and services in the EU. This means it includes all emissions that occur anywhere in the EU or the rest of the world throughout the production chain of goods and services that are used for final consumption or investment in the EU.

When examining EU greenhouse gas emissions from a consumption perspective, the highest recorded emissions were in 2012 at 11 698 kg per capita. However, emissions have gradually decreased since then, with the latest level observed in 2022 at 10 655 kg per capita.

From a production perspective, EU greenhouse gas emissions experienced a similar trend. The highest level of emissions occurred in 2012, reaching 9 530 kg per capita. Subsequently, there was a consistent reduction, with the latest emissions data recorded in 2022 at 8 060 kg per capita.

The figure also shows higher emissions from a consumption perspective ('footprints') than from a production perspective. This is due to the fact that the emissions embodied in imported goods and services for the EU's domestic consumption have been higher than the emissions embodied in the EU's exports, i.e. the EU has been a net importer of greenhouse gas emissions.

These findings indicate a positive trajectory in the EU's efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, accelerated in recent years by the decreased emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The long-term gradual decrease in both consumption and production-based emissions signifies a potential shift towards more sustainable practices and a growing awareness of the environmental consequences of economic activities. This reduction also highlights the effect of EU policymaking, especially in adopting cleaner energy sources, promoting energy efficiency, encouraging sustainable production and consumption patterns, and fostering international cooperation to address global climate challenges.

Global trading partnerships

Trade balance

International trade plays a significant role in developing the EU economy as it enables the economic growth of open economies. Traditionally, international trade in goods has been the principal channel for economic integration, but in recent times, international trade in services has become increasingly important.

Figure 6 presents the export-to-import ratio for the period 2012-2024 (goods and services). In this period, the ratio ranged from 1.03 to 1.10, indicating a consistent pattern of the EU exporting slightly more goods and services than it imports. In 2023, a sharp increase in the ratio was observed, indicating a return to pre-2022 levels, similar to those seen before the energy crisis. In 2024, the ratio increased further to 1.09.

A more detailed analysis shows that 6 out of 27 EU countries are net importers[2], meaning they import more goods and services than they export. Being a net importer could present an issue for specific countries, as they would have to borrow externally to maintain their balance of payments. However, the rest of the EU countries export more than they import.

Figure 7 shows that the development of the EU's international trade in goods and services as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) has recovered to a level higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there has been a slight decrease in 2023 and 2024 compared with 2022, with the value of exports as a percentage of GDP falling from 55.2% in 2022 to 50.7% in 2024 and the value of imports as a percentage of GDP falling from 53.3% in 2022 to 46.3% in 2024 (including both goods and services). The overall performance for the period 2012-2024 shows that the EU is a stable trade partner and remains a net exporter to the rest of the world[3].

Source: Eurostat (tet00003) and (tet00004)

Trade in intermediate goods and services and trade concentration

Trade in intermediate goods and services is a vital aspect of globalisation, reflecting the interconnectedness of economies and the complex supply chains across EU countries. The percentage of trade in intermediate goods trade with non-EU countries as a proportion of total trade in goods has displayed an upward trend over the years. In 2017, it stood at 50.5%, increasing slightly to 51.4% in 2018 and then decreasing to 51.1% in 2019. In 2020, it reached 50.6%, followed by a moderate rise to 52.6% in 2021 and reaching 56.8% in 2022, before dropping slightly again to 54.8% in 2024.

When it comes to trade in intermediate services trade with non-EU countries, the values have shown a more consistent upward trend. In 2017 and 2018, trade in intermediate services accounted for 74.2 and 74.6% of total services trade, respectively. This figure increased further to 75.8% in 2019. In 2020, there was a significant jump to 82.7%, indicating a greater reliance on intermediate services for economic activities. The figure slightly decreased to 79.0% by 2022 but remained at a high level. It is important to note that in 2020, the volume of final services experienced a significant decline, reaching its lowest levels for the period, primarily due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from early to mid-2020. This decline in trade in final services was predominantly driven by reduced spending from foreign tourists and travellers, as travel was severely limited or non-existent for much of the year. Consequently, this circumstance can account for the notable increase in the share of intermediate services in total trade in services (total services include trade in final services – e.g. travel).

These figures underscore the significance of trade in intermediate goods and services as a key driver of globalisation. EU countries rely on such trade to access necessary inputs, components, and services for the production of final goods and services. The increasing share of trade in intermediate services highlights the growing importance of services in the global economy.

Trade in goods and services with the top 5 non-EU trading partners shows the level of the EU's trade concentration or reliance on a small set of trading partner countries. The percentage of trade in goods with the top 5 trading partners as a proportion of total trade in goods has shown fluctuations over the years. In 2012, it accounted for 51.4%, increasing to 53.5% by 2016. Subsequently, it slightly decreased to 52.7% in 2018 before reaching 55.2% in 2020. In 2022, the figures decreased to 51.3%, fuelled by a sharp decline in trade in goods with Russia[4], before rising again to 52.7% in 2024.

When it comes to trade in services with the top 5 non-EU trading partners, the values have exhibited some variations as well. In 2012, trade in services with these partners accounted for 58.7% of total services trade. It then decreased to 56.1% in 2015 before rising to 58.9% in 2016. In 2019, it slightly declined to 57.2%, but saw a significant increase to 62.8% in 2022, with a peak in year 2021 (63.4%).

A relatively high concentration of trade partners in the EU may indicate a need for the EU to strengthen bilateral and multilateral trade agreements and promote a conducive trade environment. Finally, diversifying trading partners and thereby reducing the percentage of trade with the top 5 partners is key to reducing global trade dependency and increasing trade resilience.

The role of the euro currency in international trade

The euro currency facilitates international trade in the EU and reinforces the role of EU countries in the world. In 2024, the euro's influence on international trade was evident in the exports of goods from EU countries. During this year, the euro was the most widely used currency for EU exports, with a share of 51.7%, ahead of the US dollar at 31.4%. Slovenia led the pack, with 91.1% of its goods exports denominated in euros. Croatia[5] followed closely behind, with 82.8% of its goods exports conducted in euros. Among the EU countries, Ireland (14.3%) and Sweden[6] (24.4%) reported the lowest percentage of goods exports denominated in euros.

When it comes to imports of goods, the US dollar was the most used currency for imports into the EU with a share of 51.1% in 2024 ahead of the euro with 39.7%[7]. Slovenia recorded 82.8% of its goods imports denominated in euros, indicating a high reliance on the euro as the preferred currency for trade, with Latvia following (65.2%). Ireland, again, reported the lowest percentage of goods imports denominated in euros, at 21.1%. Denmark[8] followed closely behind, with 23.1% of its goods imports invoiced in euros. The available data for 2024 indicate that the share of the euro in imports and exports has been increasing steadily since 2019, at the EU level.

The euro's widespread use in international trade demonstrates its acceptance as a stable and trusted currency for conducting business transactions, enhancing trade relations, and promoting economic cooperation among EU countries and with non-EU countries. Maintaining the stability and strength of the euro remains a priority for the EU countries as it continues to contribute to the further integration and global reach of the EU economies.

Global investments

Investments in the EU and abroad

The international investment position is a vital aspect of globalisation for EU countries, representing the stock of cross-border investments and financial foreign assets held by a country. It reflects the extent of a nation's economic relationships and its position in the global financial landscape.

The international investment positions of EU countries have experienced fluctuations over the years. From 2014 to 2023, the positions consistently showed negative values, indicating that EU countries had more liabilities to foreign investors than assets held abroad. However, EU's investment position has been gradually improving, from the lowest value of -€2.5 trillion recorded in 2017, to the highest value of €0.9 trillion in 2023[9].

Foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks show the value of the investment at a specific point in time (end of the year)[10]. Figure 11 shows the development of direct investment stocks in the EU by countries from outside the EU (inward FDI) and of direct investment stocks by the EU countries in countries outside the EU (outward FDI) for the years 2013–2023. Both inward and outward investment grew steadily relative to GDP until 2016. In 2017 and 2018, a decline in both inward and outward FDI was observed. Inward and outward FDI stocks remained at a stable level from 2018 to 2021, declining in 2022 and 2023. Finally, outward investments remained higher than inward investments for 2023, showing the EU's role as a global net investor.

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_ind)

For a better understanding of inward-outward FDI, Figure 12 was created. The graph represents the balance between inward and outward FDI in each of the EU countries, with values below zero representing countries that receive more FDI than they invest and values above zero representing countries that invest more in comparison with the FDI they receive. Germany, Denmark, Finland, and France are the largest net investors, while Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia are on the other side of the extreme, being the largest net receivers of FDI.

The intensity of investment integration within the international economy is measured by the FDI flows intensity. This indicator represents the average of inward and outward FDI flows divided by GDP.

In the case of EU countries, the intensity of FDI flows has experienced fluctuations in recent years. In 2018, the indicator showed a value of -3.0%, indicating a negative level of investment integration compared to the size of the GDP. In the following years, the indicator fluctuated between -0.2% and 2.0%, suggesting a higher level of investment integration within the international economy. The trend reversed in 2023, with a negative level of FDI flow intensity of -1.5% indicating a slightly negative investment integration compared with the size of the GDP.

Benefits of EU investments

The rate of return on direct investment abroad and on direct investment in the EU is another significant aspect of globalisation. It represents the returns or profits gained from investments made by EU individuals or entities in foreign countries or within the EU countries. Understanding the rate of return on direct investment abroad and in the EU provides insights into the financial gains or losses associated with globalisation and the investment activities of individuals and entities across borders.

For the EU, the rate of return on direct investment abroad experienced fluctuations over the years. In 2013, the return stood at 4.6%, marking the beginning of a period of stability that lasted until 2021. The highest return was observed in 2023, reaching 6.0%, while the lowest return was recorded in 2020, at 3.9%.

Similarly, the rate of return on direct investment in the EU also exhibited variations during the same period. In 2013, the data showed a return of 4.8% on investments made within the EU countries. The rate remained relatively stable until 2021, at 5.2%, and then rose further to its highest value of 6.4% in 2023.

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_ind)

These fluctuations in the rate of return on direct investment abroad and in the EU highlight the changing profitability of investments made by individuals or entities in foreign countries and within the EU. Such variations can be influenced by numerous factors, including economic conditions, market dynamics, regulatory changes, and geopolitical events.

The way forward

In preparing this article, certain choices were made about which aspects of globalisation to focus on. The article's purpose is to provide some examples of economic globalisation indicators and show how they could be used.

In July 2014, Eurostat published the first set of economic globalisation indicators on a dedicated section of its website. In March 2015, globalisation indicators were added, broken down by economic activity. After 2015, Eurostat focused on improving the existing statistics and developing new business statistics related to globalisation, including experimental statistics (such as global value chains statistics). Consequently, in April 2024, the list of indicators was expanded and additionally presented in the form of a Dashboard. Eurostat will continue to improve and expand the list of globalisation indicators to be able to capture the most relevant effects of globalisation in the modern, dynamic world.

Users can find these indicators in the Globalisation dashboard and their dedicated section of Eurostat.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The set of indicators of economic globalisation

The economic globalisation indicators aim to contribute to the analysis of globalised business which is often requested by those involved in developing future policies. Data for these indicators could be collected and published within the European Statistical System (ESS).

Context

Economic globalisation is the process of internationalisation caused by or experienced by economic actors in the business economy. In practice, the main indicators of economic globalisation are defined based on the variables and breakdowns the European Statistical System (ESS) is obliged to provide under regulations such as those applying to structural business statistics, foreign affiliate statistics, national accounts and international trade in goods.

To fully understand the consequences of economic globalisation, the economic behaviour of the actors in the process should also be taken into account. The view generally held by policymakers is that the pace and direction of economic globalisation has a significant impact on employment, business dynamics, trade, investments and economic growth.

View this article online at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Economic_globalisation_indicators&action=edit

Footnotes

- Until 2021, the global value chains statistics were considered experimental statistics, meaning that the methodology of data collection significantly changes over the reference periods. ↑

- Net importers in 2024 are Belgium, Croatia, France, Greece, Latvia, and Romania. ↑

- The imports and exports include both intra-EU and extra-EU trade ↑

- The Statistics Explained article EU trade with Russia - latest developments shows a more detailed description of the trade statistics with Russia. ↑

- Croatia joined the euro area on 1 January 2024. ↑

- Sweden is not part of the euro area. ↑

- The Statistics Explained article Extra-EU trade by invoicing currency provides more details. ↑

- Denmark is not part of the euro area. ↑

- These values do not include reserve assets for the EU; taking them into account would likely shift the EU's investment position towards positive values. More information on reserve assets can be found in the Statistics Explained article on international investment position statistics. The data can be found in the Eurostat database bop_iip6_q, for the EU and for individual EU countries. ↑

- The FDI stocks are reported using the directional principle reflecting the direction of influence underlying the direct investment and is different from the presentation of investments using the asset/liability principle (see the OECD benchmark definition of FDI par. 3.4.5. ↑

Explore further

Other articles

Database

- Globalisation in business statistics (gbs), see:

- Balance of Payments (bop), see:

- EU direct investment positions, breakdown by country and economic activity (bop_fdi6_ind)

- Annual national accounts (nama10), see:

- GDP and main components (output, expenditure and income) (nama_10_gdp)