Archive:Healthcare provision statistics

- Data extracted in October 2016. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: October 2017.

(thousands)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_prs1)

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_phys) and (demo_pjan)

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_prsns)

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_prs1)

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (tps00046)

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch2)

(ISHMT) — selected diagnoses group 1, 2014

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch2)

(ISHMT) — selected diagnoses group 2, 2014

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch2)

(ISHMT) — selected diagnoses group 1, 2014

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch4)

(ISHMT) — selected diagnoses group 2, 2014

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch4)

(days)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_inpst)

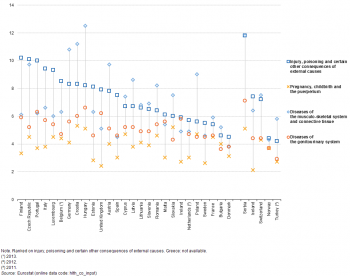

(ISHMT) — selected diagnoses group 1, average length of stay, 2014

(days)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_inpst)

(ISHMT) — selected diagnoses group 2, average length of stay, 2014

(days)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_inpst)

This article presents key statistics on non-monetary aspects of healthcare in the European Union (EU); these data complement data on healthcare expenditure. An individual’s state of health and that of the population in general is influenced by genetic and environmental factors, cultural and socioeconomic conditions, as well as the healthcare services that are available to prevent and to treat illness and disease.

Non-monetary statistics may be used to evaluate how a country’s healthcare system responds to the challenge of universal access to good healthcare, through measuring human and technical resources, the allocation of these resources and the demand for healthcare services by patients. This article presents statistics on healthcare professionals, hospital beds and hospital discharges of in-patients and day care patients.

Main statistical findings

Healthcare personnel: physicians

There were approximately 1.8 million physicians working in the EU

In 2013, there were approximately 1.8 million physicians in the EU-28 (see Figure 1), an increase of 253 thousand compared with 10 years earlier.

In the context of comparing healthcare services across EU Member States, Eurostat uses the concept of practising physicians, although for some Member States (see Table 1 for more details) data are only available for professionally active or licensed physicians.

Greece had the highest number of physicians per 100 000 inhabitants

One of the key indicators for measuring healthcare personnel is the total number of physicians, expressed per 100 000 inhabitants. In 2014, Greece recorded the highest ratio among the EU Member States, at 632 per 100 000 inhabitants (data for licensed physicians). Austria (505), Portugal (443; licensed physicians), Lithuania (431), Sweden (412; 2013 data) and Germany (411) had the next highest ratios and were the only other Member States to record in excess of 400 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants. By contrast, there were 231 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants in Poland.

Spain was the only EU Member State to report having more surgical specialists than general medical practitioners or medical specialists

Table 1 provides statistics on physicians by seven specialities or groups of specialities: the three most common across the EU Member States in 2014 (see Table 1 for data availability; no data available for Hungary or Slovakia) were the groups of generalist medical practitioners, medical specialists and surgical specialists. In 12 of the Member States, including Germany, France and the United Kingdom, generalist medical practitioners were more common than any of the other specialities or groups of specialists shown in the table. In contrast, there were more medical specialists in 13 of the Member States (including Italy), leaving Spain as the only Member State to record a higher number of surgical specialists.

In 2014, the highest ratio of generalist medical practitioners to population size was recorded in Portugal (228 per 100 000 inhabitants). The highest ratios for medical specialists were found in Greece (243 per 100 000 inhabitants), Lithuania (153) and the Czech Republic (152; 2013 data), while the highest ratios for surgical specialists were recorded in Greece (136 per 100 000 inhabitants) and Lithuania (103).

Figure 2 presents information on the gender distribution of the number of physicians. In 2014, the highest share of male physicians was recorded in Luxembourg, where close to two thirds (66.3 %) of all physicians were men. Men also accounted for a relatively high share — around 6 out of 10 — of the physicians in Cyprus, Malta, Belgium, Italy, Greece, Ireland and France. By contrast, all three of the Baltic States, as well as Romania, Croatia and Slovenia were characterised by a high proportion of female physicians, the share of women rising to 73.3 % in Estonia and 74.3 % in Latvia.

Healthcare personnel: nursing and caring professionals

Nursing professionals (ISCO 08 code 2221) assume responsibility for the planning and management of patient care, including the supervision of other healthcare workers, working autonomously or in teams with medical doctors and others in the application of preventive and curative care. Midwifery professionals (ISCO 08 code 2222) also plan, manage, provide and evaluate care services. Midwives do so before, during and after pregnancy and childbirth, providing delivery care for reducing health risks to women and new-born children; they may work autonomously or in teams with other healthcare providers. Nursing associate professionals (ISCO 08 code 3221) provide basic nursing and personal care to people suffering from the effects of ageing, illness, injury, or other physical or mental impairment; they may also provide health advice to patients and families, or monitor patients’ conditions. Nursing associate professionals generally work under the supervision of, and in support of implementation of health care, treatment and referrals plans established by medical, nursing and other health professionals. Health care assistants, or caring professionals, include all health care assistants irrespective of where they work, be they assistants in institutions (ISCO 08 code 5321), home-based personal care workers (ISCO 08 code 5322) or personal care workers not elsewhere classified (ISCO 08 code 5329).

Relatively complete data are available for 23 EU Member States concerning nursing and caring professionals (see Figure 3). In 16 of these there were more nursing professionals than other types of nursing and caring professionals, with the share of nursing professionals reaching at least 90 % of the total in Poland, Bulgaria and Cyprus. In four Member States — Spain, Italy, Finland (2012 data) and the United Kingdom — the majority of nursing and caring professionals were health care assistants, while in Croatia, Romania and Slovenia nursing associate professionals made up the largest share of nursing and caring professionals, as was also the case in Serbia.

In 2014, there were 3.4 million practising nursing professionals in the EU (no data for Belgium, the Czech Republic or the Netherlands; 2013 data for Denmark and Sweden; 2012 data for Finland; category of professionally active nursing and caring professionals for France, Italy, Portugal and Slovakia).

Luxembourg and Ireland had the highest number of nursing professionals relative to population size

Luxembourg and Ireland (professionally active) had close to 1 200 practising nursing professionals per 100 000 inhabitants in 2014, which were the highest ratios among the EU Member States; Sweden (2013 data) and Germany also recorded in excess of 1 100 practising nursing professionals per 100 000 inhabitants. The number of nursing professionals was otherwise generally within the range of 440–1 000 per 100 000 inhabitants in most of the remaining Member States, with Slovenia (244), Greece (182), Croatia (120) and Romania (56) recording lower ratios.

In 2014, there were 149 thousand practising midwives in the EU (no data for Belgium, Ireland, Spain or the Netherlands; 2013 data for Denmark and Sweden; 2012 data for Finland; professionally active for France, Italy, Portugal and Slovakia). Sweden and Poland had the highest ratios of midwives relative to their populations, at 75 per 100 000 inhabitants (2013 data) and 59 per 100 000 inhabitants respectively. At the other end of the range, by far the lowest ratio was recorded in Slovenia, where there were, on average, just 7 midwives per 100 000 inhabitants.

Health care is organised in different ways across the EU Member States and this is reflected in the data for nursing associate professionals insofar as some countries do not recognise this type of professional. Subject to data availability, there were 13 Member States where there were no nursing associate professionals. Among the other Member States, there were in total 509 thousand practising nursing associate professionals in 2014 (no data for Belgium, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands or Sweden; 2013 data for Denmark; 2012 data for Finland). Relative to population size, there were 667 nursing associate professionals in Denmark for every 100 000 inhabitants (2013 data). Slovenia and Romania also recorded more than 500 nursing associate professionals per 100 000 inhabitants, while Croatia and Finland (2012 data) recorded ratios of more than 400 nursing associate professionals per 100 000 inhabitants.

The number of health care assistants per 100 000 inhabitants in Finland and the Netherlands was considerably higher than in the other EU Member States

There were 2.8 million health care assistants working in the EU in 2014 (no data for Belgium, Germany, Cyprus, Poland or Sweden; 2013 data for Denmark; 2012 data for Finland; professionally active for France, Italy and Slovakia). Finland had more than 2 000 practising health care assistants per 100 000 inhabitants in 2012, which was the highest ratio among the EU Member States, while the Netherlands had a ratio of just over 1 400 per 100 000 inhabitants; the United Kingdom and Italy were the only other Member States to record at least 1 000 practising health care assistants per 100 000 inhabitants.

Healthcare personnel: dentists, pharmacists and physiotherapists

Dentists (ISCO 08 code 2261) diagnose, treat and prevent diseases, injuries and abnormalities of the teeth, mouth, jaws and associated tissues. Pharmacists (ISCO 08 code 2262) store, preserve, compound, dispense and sell medicinal products (irrespective of location) and may also provide advice on the proper use and adverse effects of drugs and medicines following prescriptions issued by medical doctors and other health professionals. Physiotherapists (ISCO 08 code 2264) assess, plan and implement rehabilitative programs that improve or restore human motor functions, maximise movement ability, relieve pain syndromes, and treat or prevent physical challenges associated with injuries, diseases and other impairments.

Figure 5 provides an overview for 2014 of the number of dentists, pharmacists and physiotherapists practising in the EU Member States. There were over 340 thousand dentists in the EU-28, over 440 thousand pharmacists and nearly 540 thousand physiotherapists (see Figure 5 for information concerning differences in data coverage for individual Member States).

Greece had the highest number of dentists per 100 000 inhabitants

On the basis of a comparison in relation to population numbers, among the EU Member States Greece recorded the highest number of dentists, at 126 per 100 000 inhabitants (data for licensed dentists). This was considerably higher than in any of the other EU Member States, as Cyprus and Bulgaria (both 98) had the next highest ratios. By contrast, there were fewer than 50 dentists per 100 000 inhabitants in Slovakia (49; professionally active dentists), Malta (37) and Poland (34).

Finland had the highest number of pharmacists per 100 000 inhabitants

Taking into account the size of each country in population terms, Finland recorded the highest number of pharmacists per 100 000 inhabitants, at 127 in 2012. Access to pharmacists was also relatively high in 2014 in Belgium (120 per 100 000 inhabitants), as well as Ireland (licensed pharmacists), Spain, Malta, Italy (professionally active), Greece (professionally active), Lithuania (licensed pharmacists) and France. The majority of the EU Member States reported 51–86 pharmacists per 100 000 inhabitants, although the Netherlands (27professionally active) and Cyprus (22) were below this range.

Finland also had the highest number of physiotherapists per 100 000 inhabitants

The relative distribution of physiotherapists across the individual EU Member States was more diverse than for dentists or pharmacists, ranging from 247 per 100 000 inhabitants in sparsely populated Finland (2012 data) down to 5 per 100 000 inhabitants in Romania.

Hospital beds

Hospital bed numbers provide information on the healthcare capacity of hospitals, in other words on the maximum number of patients who can be treated.

The number of hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants averaged 521 in the EU-28 in 2014. The reduction in bed numbers between 2004 and 2014 across the whole of the EU-28 was equal to 71 fewer beds per 100 000 inhabitants. This reduction may reflect, among other factors, economic constraints, increased efficiency through the use of technical resources (for example, imaging equipment), a general shift from in-patient to out-patient operations, and shorter periods spent in hospital following an operation or treatment.

Two thirds of all beds in EU-28 hospitals were for curative care

An analysis of the type of care provided in hospital beds, identifying curative care beds, rehabilitative care beds, long-term care beds and other hospital beds, is provided in Figure 8. Across the EU-28 around three quarters of beds were used for curative care the remainder (24 %) for other purposes. Among the EU Member States, the proportion of hospital beds used for curative care exceeded 90 % in Cyprus, Portugal, Denmark, Ireland, Slovenia, Sweden and Belgium. Rehabilitative care beds accounted for one quarter or more of all hospital beds in France, Poland and Germany in 2014, while the share of long-term care beds was around one quarter in the Czech Republic and Hungary and reached 30 % in Finland.

Lithuania had the highest number of curative care beds relative to population size

Among the EU Member States, the ratio of curative care beds to population size ranged from 227 beds per 100 000 inhabitants in the United Kingdom to 631 per 100 000 inhabitants in Lithuania; among the non-member countries for which data are available Liechtenstein (164) was outside this range. Note that for the United Kingdom only beds in public hospitals are included while the same is true in Ireland, Montenegro, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Serbia.

Figure 9 also shows the availability of hospital beds for all types of psychiatric care: note that beds for psychiatric care are also included in the values for the four types of care (curative, rehabilitative, long-term and other). The availability of psychiatric care beds relative to population size was particularly high in Belgium (173 per 100 000 inhabitants) and this ratio also exceeded 100 per 100 000 inhabitants in Malta, Germany, Latvia and Lithuania.

Hospital discharges of in-patients and day care patients

Output-related indicators focus on hospital patients. Two such indicators are the number of hospital discharges (shown in this article for in-patients and day care patients) and the average length of stay for in-patients.

In 2014, there were in excess of 83.8 million discharges of in-patients (based on latest available data) in the EU-28, around 16.5 thousand per 100 000 inhabitants. There was a wide range in in-patient discharge rates between EU Member States in 2014 (see Figure 10). These peaked at 31.5 thousand discharges per 100 000 inhabitants in Bulgaria, while there were also relatively high numbers of discharges per 100 000 inhabitants in Austria (26.3 thousand) and Germany (25.0 thousand). By contrast, the lowest number of discharges per 100 000 inhabitants — below 10 thousand — were recorded in two of the southern EU Member States, namely, Portugal and Cyprus, while Spain and Italy recorded the next lowest hospital discharge rates.

In nearly all Member States diseases of the circulatory system were the most common diagnosis among hospital discharges of in-patients

Diseases of the circulatory system were often the most common diagnosis among hospital discharges of in-patients (see Figures 11 and 12). One quarter of the EU Member States reported in excess of 3 000 discharges of in-patients per 100 000 inhabitants for diseases of the circulatory system. The Member States where other diagnoses were more common were Ireland (where pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium was the most common diagnosis) and the United Kingdom (where diseases of the respiratory system was the most common diagnosis). Note that for Cyprus the discharge rates for most of the selected diagnosis are particularly low as a relatively large proportion of discharges have unknown diagnoses and are coded under a remainder heading.

Among the EU Member States (leaving aside data for Cyprus), discharge rates for in-patients varied greatly for one of the diagnoses shown in Figure 12: diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue. The lowest discharge rate for these diseases was 377 per 100 000 inhabitants in Portugal, while the highest was more than eight times as high, 3 197 per 100 000 inhabitants in Austria.

For day care patients, the two most common diagnoses were diseases of the genitourinary system and neoplasms

Similar information for day care patients is shown for the same eight diagnoses in Figures 13 and 14. In 2014, there were in excess of 35 million discharges of day care patients (based on latest available data) in the EU-28, around 7.3 thousand per 100 000 inhabitants. Relative to population size (see Figures 13 and 14), among the most common diagnoses were diseases of the genitourinary system and neoplasms — reflecting the use of day care for some cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and some kidney disease treatments such as dialysis — although there were many exceptions.

Average length of stay of in-patients

Men generally had longer average lengths of stay as in-patients than women

The average length of a hospital stay as an in-patient ranged from 5.2 days in the Netherlands (2012 data) to 9.6 days in Croatia in 2014, with Finland above this range (see Figure 15). Note that in the Netherlands, as well as in several other EU Member States, the data presented in Figures 15 and 16 exclude discharges from psychiatric hospitals or mental health care institutions, which generally report a longer average length of stay. The average length of stay for in-patients was generally longer for men than for women, with only Finland, Hungary, Malta, Belgium (2013 data) and Austria reporting the reverse situation and Germany reporting the same averages for both sexes; the largest gender difference was observed in Croatia, where men spent an average of 1.5 days more in hospital per stay.

Among the eight diagnoses presented in Figures 16 and 17, the average length of stay for in-patients was normally longest for diseases of the circulatory system or neoplasms.

Among the other diagnoses, diseases of the musculo-skeletal system and connective tissue stand out because of their wide range among the EU Member States for the average length of stay: in Denmark this was 3.8 days whereas in Germany, Croatia and Hungary it was over 10 days. By contrast, for several of the diagnoses shown in these two figures there was a relatively high degree of uniformity in the average length of stay reported by each EU Member State. For example, in-patients diagnosed with diseases of the digestive system spent on average between 4.5 days (in Bulgaria and Sweden) and 7.1 days (in Croatia) in hospital; patients diagnosed with diseases of the genitourinary system, diseases of the respiratory system or neoplasms also reported quite similar average lengths of stay across most of the Member States.

Data sources and availability

Eurostat, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) have established a common framework for a joint healthcare data collection. Following this framework, EU Member States submit their data to Eurostat on the basis of a gentlemen’s agreement. The data collected relates to statistics on human and physical resources in healthcare — supplemented by additional Eurostat data on hospital activities (discharges and procedures) — as well as healthcare expenditure following the methodology of the system of health accounts (SHA).

Non-expenditure healthcare data are mainly based on administrative national sources; a few countries compile this information from surveys. As a consequence, the information collected may not always be comparable. Information on the non-expenditure component of healthcare can be divided into two broad groups of data:

- resource-related healthcare data on human, physical and technical resources, including personnel (such as physicians, dentists, nursing and caring professionals, pharmacists and physiotherapists) and hospital beds;

- output-related data that focuses on hospital patients and their treatment(s), in particular for in-patients.

Hospitals are defined according to the classification of healthcare providers within the SHA; all public and private hospitals should be covered.

Note on tables: data are not available for cells which include the symbol ':'.

Healthcare personnel — methodology

Statistics on healthcare resources — including personnel — are documented in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions.

Common definitions have been agreed between Eurostat, the OECD and the WHO with respect to the employment of various health care professionals. Three main concepts are used to present this data; Eurostat gives preference to the concept of ‘practising’ health care professionals:

- ‘practising’, in other words, health care professionals providing services directly to patients;

- ‘professionally active’, in other words, ‘practising’ professionals plus health care professionals for whom their medical education is a prerequisite for the execution of their job;

- ‘licensed’, in other words, health care professionals who are registered and entitled to practise as health care professionals.

Data on personnel are classified according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO): see codes 221 (medical doctors), 222, 322 and 532 (nursing and caring professionals) and 226 (including dentists, pharmacists and physiotherapists).

For country specific notes, please refer to these background information documents:

- physicians;

- physicians by speciality;

- dentists;

- nursing and caring professionals;

- pharmacists;

- physiotherapists.

Hospital beds — methodology

Statistics on healthcare resources — including beds in hospitals — are documented in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions.

Hospital beds are those beds which are regularly maintained and staffed and immediately available for the care of admitted patients. Both occupied and unoccupied beds are included. Excluded are recovery trolleys and beds for same day care (day care and out-patient care), provisional and temporary beds. Hospital beds are presented for four categories:

- Curative care beds in hospitals are for patients where the principal clinical intent is to do one or more of the following: manage labour (obstetrics), cure illness or provide definitive treatment of injury, perform surgery, relieve symptoms of illness or injury (excluding palliative care), reduce severity of illness or injury, protect against exacerbation and/or complication of illness and/or injury which could threaten life or normal functions, perform diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Beds for palliative and long-term nursing care are recorded under long-term care.

- Rehabilitative care beds in hospitals are beds accommodating patients for services with the principle intent to stabilise, improve or restore impaired body functions and structures, compensate for the absence or loss of body functions and structures, improve activities and participation and prevent impairments, medical complications and risks.

- Long-term care beds in hospitals are for patients requiring long-term care due to chronic impairments and a reduced degree of independence in activities of daily living, including palliative care.

- Psychiatric care beds in hospitals are for patients with mental health problems. Included are all beds in mental health hospitals, as well as beds in psychiatric departments of general and specialised hospitals.

These statistics on hospital beds should include public as well as private sector establishments although some EU Member States provide data only for the public sector, for example, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Montenegro, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Albania and Serbia.

For country specific notes on this data collection, please refer to this background information document: hospital beds by type of care.

Hospital discharges and average length of stay — methodology

Statistics on healthcare activities — including discharges and average length of stay — are documented in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions.

Output-related indicators focus on hospital patients and cover the interaction between patients and healthcare systems, generally through the form of the treatment they receive. Data are available for a range of indicators including hospital discharges of in-patients and day cases by age, gender, and selected (groups of) diseases; the average length of stay of in-patients; or the medical procedures performed in hospitals. The number of hospital discharges is the most commonly used measure of the utilisation of hospital services. Discharges, rather than admissions, are used because hospital abstracts for in-patient care are based on information gathered at the time of discharge.

For country specific notes on this data collection, please refer to this background information document: hospital discharges by diagnosis (ISHMT).

Context

Health outcomes across the EU are strikingly different according to where people live, their ethnicity, sex and socioeconomic status. In addition, the structure of healthcare services in the EU also varies in terms of funding, provision and organisational arrangements across countries and with respect to their public–private mix. The EU promotes the coordination of national healthcare policies through an open method of coordination which places particular emphasis on the access to, and the quality and sustainability of healthcare. Some of the main objectives include: shorter waiting times; universal insurance coverage; affordable care; more patient-centred care and a higher use of out-patients; greater use of evidence-based medicine, effective prevention programmes, generic medicines, and simplified administrative procedures; and strengthening health promotion and disease prevention.

Directive 2005/36/EC on the recognition of professional qualifications provides a Europe-wide legal framework enabling EU Member States to recognise each other’s qualifications. A range of health professionals — including doctors, dentists, pharmacists and physiotherapists — enjoy automatic recognition, in other words, if they are a certified practitioner in their home country then they are automatically entitled to practice anywhere else in the EU.

One consequence of ongoing and future demographic developments is that the number of elderly persons (aged 65 and over) in the EU-28 is forecast to increase by almost 60 % during the period 2014–2054 (Eurostat; EUROPOP 2013 main scenario). The ageing of the EU’s population is likely to result in considerable demand for a range of age-related services, as an increasing proportion of the population becomes frail and suffers from declining physical and mental health. European healthcare systems will therefore need to anticipate needs for future skills in order to match the supply of health professionals, for example nurses and caring professionals, to the demands of an increasingly aged society, and to accommodate a probable shift away from care in hospitals towards care in the home. An action plan for the EU health workforce seeks to help EU Member States tackle the challenge of an increase in the demand for healthcare, by: improving workforce planning and forecasting; anticipating future skills’ needs; improving the recruitment and retention of health professionals; mitigating the negative effects of migration on health systems. The plan is part of the broader strategy ‘Towards a job-rich recovery’ (COM(2012) 173).

See also

Online publications

Healthcare human and physical resources

- Physicians

- Nursing and caring professionals

- Dentists, pharmacists and physiotherapists

- Beds

- Technical resources and medical technology

Healthcare activities

- Hospital discharges and length of stay

- Surgical operations and procedures

- Consultations

- Preventive services

- Medicine use

- Unmet needs for health care

Methodology

General health statistics articles

- Health statistics introduced

- Health statistics at regional level - healthcare resources

- Healthcare expenditure

- The EU in the world — health

Further Eurostat information

Main tables

Database

- Health care resources (hlth_res)

- Health care activities (hlth_act)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Health care resources (ESMS metadata file — hlth_res)

- Health care activities (ESMS metadata file — hlth_act)

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

External links

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — European Core Health Indicators (ECHI)

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — Health Systems Performance Assessment

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — Health workforce

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — Public health

- Joint OECD / European Commission report ‘Health at a Glance: Europe’

- OECD — Health policies and data

- World Health Organisation (WHO) — Health systems