CEEDS: new ways of exploring big data

date: 06/08/2014

Project: Collective Experience of Empathic Data S...

acronym: CEEDS

See also: CORDIS

Contact: Contact

Big Data refers to large amounts of data produced very quickly by a high number of diverse sources. Data can either be created by people or generated by machines, such as sensors gathering climate information, satellite imagery, digital pictures and videos, purchase transaction records, GPS signals, etc. It covers many sectors, from healthcare to transport and energy.

Data has become a key asset for the economy and our societies, similar to the classic categories of human and financial resources. Analysts today are confronted with vast inflows of data they need to sift through to find solutions to modern challenges.

Whether it is geographical information, statistics, weather data, research data, transport data, energy consumption data, or health data, the need to make sense of "Big Data" is leading to innovations in technology, development of new tools and new skills. This, indeed, is one of the important challenges in the ICT part of the EU’s new Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.

There may also be help at hand in evaluating Big Data and our handling of it from an unlikely source... our subconscious. Since we are only aware of about 10% of our brain activity, the CEEDS project has been looking at ways to unlock the other 90%, to see if it can in some way help us find what we are looking for.

USING VIRTUAL REALITY TOOLS TO ENTER LARGE DATASETS

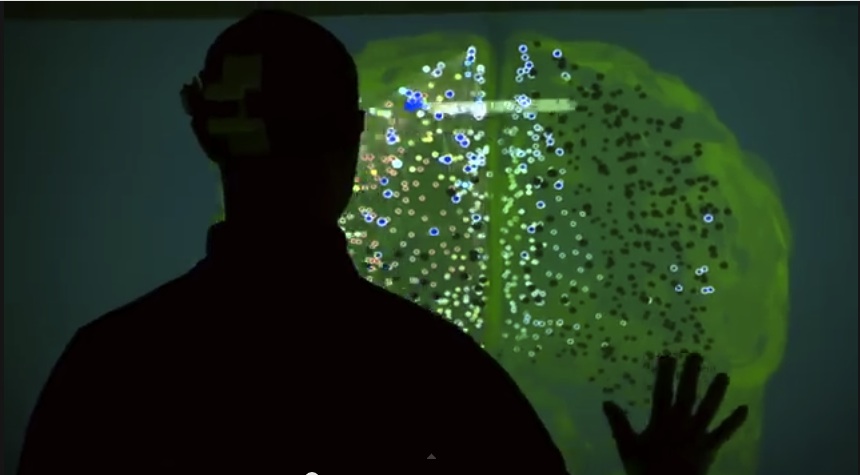

CEEDS – Collective Experience of Empathic Data Systems – is trying to make the subconscious ‘visible’ by gauging our sensory and physiological reactions to the flow of Big Data before us. Researchers from the project have built a machine that uses virtual reality tools to enter these large datasets. Employing a range of visual, audio and tactile sensor systems, it also monitors users’ responses to the experience to find out what they focus on and how they do it.

The CEEDS eXperience Induction Machine (XIM), located at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, is designed to help analysts assimilate Big Data better. But by monitoring their reactions, it also provides feedback that could be useful in designing data presentations that are more accessible in the future.

Neuroscientists were the first group the CEEDs researchers tried their machine on. It took the typically huge datasets generated in this scientific discipline and animated them with visual and sound stimuli.

The immersive 3D chamber examining users’ reactions to data contains a panoply of devices. Motion sensors track postures and body movements. An eye tracker tells the user where to focus and checks pupil dilation for signs of stress. A glove ‘feels’ hand movements, measures grip and skin responses. Cameras analyse facial expressions. Voice equipment detects emotional characteristics in what a user says or utters. And a specially-developed vest is worn to monitor heartbeat and breathing patterns.

The neuroscientists’ reactions to the data were measured. And, by providing them with subliminal clues, such as flashing arrows they were not aware of, the machine guided them to areas that were potentially more interesting to them. It also helped when they were getting tired or overloaded with information by changing the presentation to suit their moods. CEEDS coordinator, Professor Jonathan Freeman, a psychologist at Goldsmiths University of London, explained: ‘It helps users by simplifying visualisation of the data when it is too complex or stressful for them to assimilate, and intensifying the presentation when the user appears bored.’

SPEEDING UP DATA ANALYSIS HAS GREAT VALUE

This CEEDS approach is novel in that, although many of its components are already available separately, no one has brought them together before with one purpose: to optimise human understanding of big data.

Possible applications for CEEDS abound, from inspection of satellite imagery and oil prospecting, to astronomy, economics and historical research. ‘Anywhere where there’s a wealth of data that either requires a lot of time or an incredible effort, there is potential,’ added Prof Freeman. ‘We are seeing that it’s physically impossible for people to analyse all the data in front of them, simply because of the time it takes. Any system that can speed it up and make it more efficient is of huge value.’

Future development of CEEDS might also go over Big Data; it can help with gathering feed-back from users in physical environments such as shops, museums, libraries. Performing artists and DJs also realize now that they could get real-time feedback from audiences wearing, say, wristbands gauging their dance intensity, body temperatures and sweat levels. And in the classroom, professors could teach students more by linking them up to their own subconscious reactions to, say, diagrams. Another application CEEDs researchers have studied is how they can feed the experience of archaeologists in identifying, for instance, 2000-year-old pottery pieces, back into databases to speed up their matching potential in the future.

CEEDS, which has 16 partners in nine countries, received EUR 6.5 million from the EU’s 7th Framework Programme as a Future and Emerging Technologies project.

Translations in French, German, Spanish, Italian and Polish soon available

Picture © specs.upf.edu