Better precipitation forecasting for half the world’s population

Related topics

Environment & climate action Innovation France Italy Netherlands Spain Environment China India Japandate: 23/09/2015

Project: Coordinated Asia-European long-term Obse...

acronym: CEOP-AEGIS

See also: CORDIS

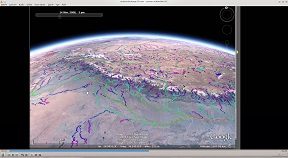

The Ceop-Aegis project has developed mathematical models to analyse the water balance and predict river flows on the world’s highest and largest plateau. These models, which combine ground-based measurements and satellite data, can notably be used to forecast droughts and floods. They are also of considerable interest for research into the effects of climate change, to which this area is particularly susceptible.

“In the watersheds we are talking about, there are 2.5 billion people — a large part of mankind,” says Massimo Menenti, who coordinated the project on behalf of the University of Strasbourg, France.

“Meltwater from snow and glaciers constitutes the largest part of these populations’ water supply,” Menenti explains. Accelerated melting of glaciers or snow, disrupted precipitation patterns, and changes affecting the monsoon rains on which the entire area relies could have profound implications.

Modelling the way of water

The sheer size of the area to be covered was one of the project’s main challenges, and the complexity of its hydrological processes was another, Menenti notes. “We are talking about 2.4 million square kilometres, including all the headwaters of the large rivers streaming down the plateau — the Yellow River, the Yangtze, the Ganges, the Indus and so on,” he adds.

The project developed applications to secure data for every variable affecting the water balance, such as precipitation, snow cover, and evaporation. “All these data streams were then fed into a hydrological modelling system to calculate the water balance for areas of 5x5 km along with the river flows in the entire region,” Menenti explains. The data was also used in an atmospheric model linking surface conditions with weather and precipitation forecasts.

The underlying time-series data is generated by ground-based measurements and monitoring, but also by satellites used for earth observation. It provides a comprehensive picture that can be analysed to detect indications of a drought or an impending flood. A website providing information on emerging droughts has already been set up, Menenti reports, and the development of a similar system for floods is in progress.

High mountains, high stakes

The Tibetan or Himalayan Plateau is often referred to as the “Third Pole”, in reference to its many glaciers, snowy peaks and frozen expanses. It is a gigantic reservoir of water, but highly exposed to climate change, Menenti notes. Many countries depend on this water, and global warming could jeopardise the stability of their supply.

The plateau and the watersheds extend across several borders, and therefore transboundary cooperation and data flows are needed to study it comprehensively. Research institutions from India and China were involved in Ceop-Aegis, along with partners from Europe and Japan.

The modelling system they jointly developed has helped to advance understanding of the river flows in the region. It has also helped to demonstrate the feasibility and usefulness of this combination of ground-based measurement and monitoring from space, contributing valuable insights for the construction of the Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS), Menenti reports.

Ceop-Aegis ended in April 2013, having delivered sophisticated modelling tools and methodology, comprehensive data sets, and inspiration for nearly 200 students who produced their Master’s and PhD theses in the framework of the project, Menenti notes.

“Thanks to the large number of people that are continuing to work on this subject, the results of the project will not be lost,” he concludes. His role in the project earned him an “Etoiles de l’Europe” (Stars of Europe) award in December 2013, a prize presented by the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research to coordinators of particularly successful EU-funded research projects led from France.