Data extracted in March 2021

The aim of this article is to provide to the users an overview on the methodological and analytical framework of asylum and Dublin statistics collected by Eurostat. Methodological concepts, classifications and definitions as well as the scope, purposes and limitations of those statistics are presented, with particular attention paid to the links with the related EU Directives adopted in the field of asylum and managed migration.

Main points

- Asylum statistics and ‘Dublin’ statistics present various types of information on the number and characteristics of non-EU citizens seeking protection in the EU and in European Free-Trade Area (EFTA) countries.

- Asylum statistics mainly focus on the number of asylum seekers and, of these, the number of non-EU citizens who have been granted a protection status.

- European asylum statistics also include ‘Dublin’ statistics, which provide information on the various steps of the so-called Dublin procedure, which aims at determining the Member State responsible for an asylum applicant in line with Regulation (EU) No 604/2013 (Dublin III).

- Asylum statistics and Dublin statistics are derived from administrative sources and registers. A large part of the collected statistics are related to EU directives on international protection.

- Asylum and Dublin statistics are available from the reference year 2008, and are collected with a monthly, quarterly and annual frequency for asylum statistics and annual frequency for Dublin statistics.

- Eurostat is engaged in ongoing methodological work to improve the harmonisation of those statistics at EU level.

- Starting in 2021, new variables and new breakdowns are collected following the amendment of the EU Regulation on Community statistics on migration and international protection (Regulation (EC) No 862/2007).

General presentation and definition

Scope of asylum statistics and Dublin statistics

Asylum statistics and Dublin statistics are derived from administrative sources. A significant part of the collected statistics are directly related to EU directives and regulations [1] on international protection. The statistical unit for those statistics is the person. This means that the data provided count the number of people covered by an administrative event (e.g. an asylum application or a Dublin request) and not the number of administrative events. For asylum statistics, a person must be counted only once during a given reference period. Therefore, the measurement unit in asylum statistics is the number of asylum applicants during a given reference period [2]. This is not the case for Dublin statistics, where each submitted or received request/decision/transfer concerning the same person during the same reference period must be reported (implying that one person can be reported more than once during a given reference period by the same Member State). The measurement unit for Dublin statistics thus corresponds to the number of requests/decisions/transfers at individual level.

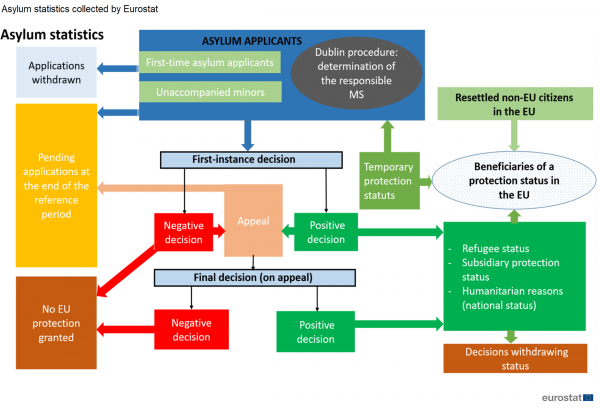

Up to 2020, asylum statistics available in Eurostat's database [3] provide data reported by EU Member States and EFTA countries on the following three categories of people: (i) asylum seekers (asylum applicants); (ii) beneficiaries of protection granted; and (iii) non-EU citizens already benefiting from international protection in non-EU countries resettled in the EU and in EFTA countries. The main variables of interest in these statistics are: (i) whether the person is a first-time asylum applicant; (ii) whether an asylum applicant is an unaccompanied minor; (iii) first-instance decisions on applications; (iv) final decisions taken on appeal or review on asylum applications; and (v) the number of resettled persons. All those statistics refer to ‘flows’, i.e. recording these variables in a given month or year. The total number of pending applications at the end of a given reference period refers to a ‘stock’.

Following the amendment of the EU Regulation [4] on Community statistics on migration and international protection, Eurostat provides – starting in 2021 – statistics on the number of: (i) subsequent asylum applicants (flow data); (ii) asylum applicants under accelerated procedure (flow data); and (iii) applicants benefiting from material reception conditions (stock data at the end of the year).

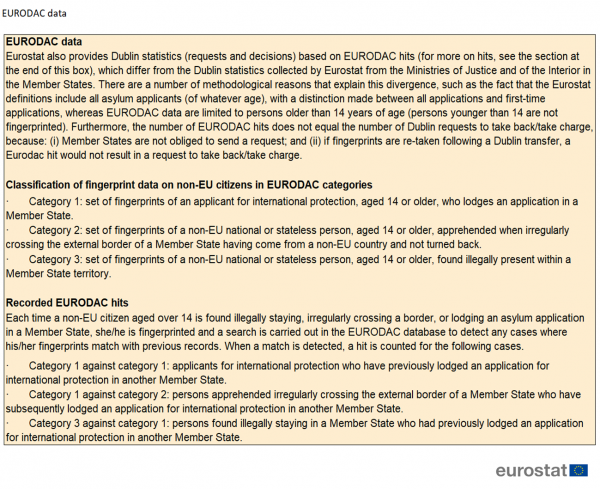

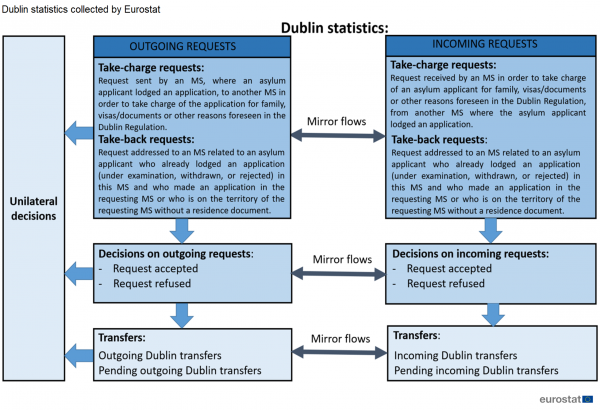

Dublin statistics provide data on the implementation of the Dublin Regulation, which lays down the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an asylum application lodged by an asylum seeker. The main variables of interest in Dublin statistics are related to the ‘taking back’ or ‘taking charge’ requests of asylum seekers sent by a Member State to another Member State under the Dublin procedure. ‘Outgoing requests’ correspond to requests sent by Member States and ‘Incoming requests’ correspond to requests received by Member States. In particular, collected Dublin statistics cover the number of requests, the number of decisions, and the number of transfers made under Dublin requests. Because EURODAC [5] plays a crucial role in the Dublin procedure, the number of requests and decisions based on the EURODAC system is also collected and disseminated by Eurostat. Most of the Dublin statistics are flows, with the exception of statistics on pending Dublin requests and transfers (incoming and outgoing), which are stocks.

Asylum statistics are broken down by age, sex and citizenship of the asylum applicants; by type of application; and by type of decision. Dublin statistics are broken down by type of request, by type of decision, and by status of transfer. Table 1 presents an overview of the main variables in asylum statistics and Dublin statistics and their availability (including available breakdowns), while Table 2 provides details of the classifications and breakdowns used in asylum statistics and Dublin statistics. Monthly and quarterly data are available 2 months after the end of the reference period, and annual data are available 3 months after the end of the reference period (except for data on the number of applicants benefiting from material reception conditions at the end of the year, which must be available 6 months after the end of the year).

On available breakdowns, the amended EU Regulation on Community statistics on migration and international protection has introduced new breakdowns for asylum statistics and Dublin statistics, in particular a breakdown that covers the status of minors. Those new breakdowns have been available starting in 2021.

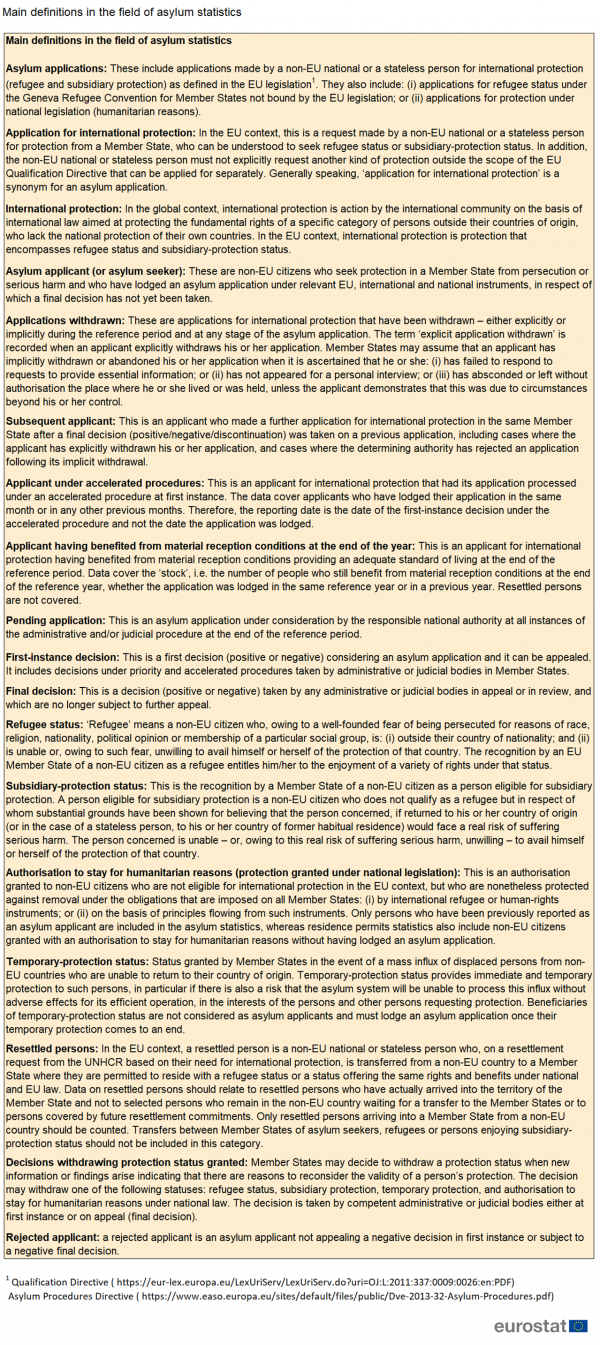

Main concepts and definitions

Asylum statistics

The lodging of an asylum application by a non-EU citizen is the primary administrative event at the origin of all asylum statistics and Dublin statistics with the exception of data on resettled non-EU citizens who are already benefiting from an international protection status.

An asylum application is generally defined as an application made by non-EU nationals or stateless persons, which can be understood as a request for protection under the Geneva Refugee Convention and Protocol or national refugee law. In the context of EU legislation on asylum (the Common European asylum system - CEAS), the term most commonly used is ‘application for international protection’, which is defined as a request made by a non-EU national or a stateless person for refugee status or subsidiary-protection status, who does not explicitly request another kind of protection. The CEAS has a set of agreed rules which lay down: (i) common procedures for international protection; and (ii) a uniform status for those who are granted refugee status or subsidiary protection. These rules are based on the full and inclusive application of the Geneva Refugee Convention and Protocol and they aim to harmonise asylum systems in the EU and reduce the differences between Member States on the basis of binding legislation. However, Ireland, which has not adopted the single asylum procedure, continues to use the term ‘application for asylum’ for an application for protection under the Geneva Refugee Convention. The term ‘protection for humanitarian reasons’ is a form of protection which is not harmonised at EU level and based on national legislation. In most of the EU Member States, the EU harmonised ‘subsidiary protection’ status has replaced the ‘protection for humanitarian reasons’ status, which still remains in some EU Member States, such as Germany, Italy or Finland.

From a statistical point of view, the term ‘asylum application’ thus covers all the requests for protection lodged by non-EU citizens including: (i) requests for international protection under the EU harmonised framework; (ii) requests for protection under the Geneva Refugee Convention and Protocol; and (iii) requests for protection under national legislation.

An asylum applicant or asylum seeker is thus defined as a non-EU national or stateless person who has lodged an asylum application or who has been included in such an application as a family member in respect of which a final decision has not yet been taken during the reference period. An asylum application must be deemed to have been lodged once a form submitted by the applicant – or a report prepared by the authorities – has reached the competent authorities of the Member State concerned. The date of the lodging of the asylum application will determine the reference period (month, year) in which an asylum applicant will be reported in the statistics. For example, a non-EU citizen arrives at the border of Greece on 29 August 2018 and informs the Greek authorities that he/she wishes to lodge an application for international protection. However, if his/her application is only recorded by the Greek asylum service on 1st September 2018, then this asylum applicant will be reported in the asylum statistics of Greece in September 2018. An asylum applicant can lodge an asylum application on arrival at the border or from within the country, and can have entered the territory legally (e.g. as a tourist) or illegally.

Asylum statistics count the number of asylum applicants at each stage of the asylum procedure, from the lodging of an asylum application to the final outcome of the asylum procedure (application withdrawn, first and final decision). This differs from Dublin statistics, which count the number of asylum applicants subject to the Dublin procedure at each stage of this procedure to determine the Member State responsible for an asylum applicant. Dublin statistics could thus be considered a subset of the asylum statistics that focus on the redistribution between Member States of asylum applicants subject to the Dublin procedure.

In Eurostat data for asylum applicants, the term ‘first-time asylum applicants’ covers non-EU citizens who lodged an application for asylum for the first-time in a given Member State. The term ‘first-time’ implies no time limits, and therefore a person can be recorded as first-time applicant only if he or she has never applied for international protection in the reporting country in the past, irrespective of whether he or she is found to have applied in another EU Member State. The number of first-time asylum applicants is a major indicator in asylum statistics, since it estimates the number of non-EU citizens arriving during a given reference period and seeking asylum for the first-time in a Member State or an associated country. When aggregating Member-State statistics, it must be kept in mind that this EU aggregate can include double-counting of asylum applicants that lodged a first application in several Member States. For more detail, this issue of the over-estimation of the EU aggregate is discussed below in the section on methodological issues.

In addition to first-time asylum applicants, the total number of asylum applicants during a given reference period also includes repeated asylum applicants. A repeated asylum applicant is a non-EU citizen who made a new application for international protection in a given Member State after a final decision (positive/negative/discontinuation) was taken on a previous application. The issues mentioned above about aggregation or double-counting of monthly data or EU Member-State data are also valid for the total number of asylum applicants.

Among Eurostat statistics on asylum applicants, special focus is given to unaccompanied minors. Unaccompanied minors are defined as non-EU citizens below the age of 18, who arrive on the territory of the Member States unaccompanied by an adult responsible for them, whether by law or custom, and for as long as they are not effectively taken into the care of such a person. Unaccompanied minors include minors who are left unaccompanied after they have entered the territory of the Member States. The age of unaccompanied minors reported in those statistics refers to the age accepted by the national authority. If the responsible national authority carries out an age-assessment procedure in relation to the applicant claiming to be an unaccompanied minor, the age reported in this table will be the age determined by the age-assessment procedure.

Other asylum statistics collected by Eurostat deal with the various possible statuses or outcomes of an asylum application. As shown in Figure 1, the possible statuses or outcomes of an asylum application are the following:

- application withdrawn;

- pending application waiting for a decision;

- a positive or negative decision at first and final instance.

When a positive decision is taken, either first or final, it will provide the asylum applicant with a protection status that could be:

- refugee status;

- subsidiary-protection status;

- protection for humanitarian reasons (protection granted under the umbrella of national legislation).

If there is a mass influx of displaced persons from non-EU countries who are unable to return to their country of origin, the EU can provide immediate temporary protection. Even though this possibility has not been used since 2008, potential beneficiaries of such protection are not considered as asylum applicants, and once temporary protection ceases, they would need to lodge an ordinary asylum application to obtain a protection status.

Lastly, the number of non-EU citizens from a non-EU country resettled in a Member State is collected every year by Eurostat. To estimate the total number of non-EU citizens granted a protection status in the EU, it is necessary to add the total number of positive decisions (first and final) and the number of resettled persons.

It should be highlighted that each of the statuses granted by Member States can be withdrawn by a competent authority. Competent authorities can revoke, end or refuse to renew the following statuses granted to an asylum applicant: (i) refugee status; (ii) subsidiary-protection status; (iii) humanitarian-protection status; or (iv) temporary-protection status. A withdrawal decision can be taken either at first or final instance.

1 Qualification Directive and Asylum Procedures Directive

Dublin statistics

Determination of the Member State responsible for an asylum applicant

Under the Dublin procedure, a ‘Dublin request’ addressed by one Member State to another Member State is the initiating action which launches the Dublin procedure to determine which Member State is responsible for an asylum applicant who has been present on the territory of at least two Member States. Two main types of request can be distinguished:

- a take-charge request;

- a take-back request.

A take-charge request occurs when an asylum applicant has lodged an application in a Member State, and this Member State may send a take-charge request to another Member State to ask that other Member State to take charge of the asylum applicant if the asylum applicant meets one of the following conditions provided for in the Dublin Regulation:

- the asylum applicant has family members in another Member State that have lodged an asylum application or that benefit from protection;

- the asylum applicant has been previously granted visas/residence documents by another Member State;

- the asylum applicant illegally crossed the border of another Member State from a non-EU country during the last 12 months;

- the asylum applicant stayed irregularly for a continuous period of at least 5 months in another Member State;

- the asylum applicant entered into the territory of another Member State in which the need for him or her to have a visa is waived;

- the asylum applicant lodged an application in an international-transit area of an airport in another Member State;

- the asylum applicant is dependent on non-EU citizens in another Member State;

- the asylum applicant needs to join non-EU citizens in another Member State for humanitarian reasons.

A take-back request occurs if an asylum applicant either lodged an application or is illegally present in a Member State. This Member State can then send a take-back request to another Member State if the asylum applicant has previously lodged an asylum application (either under examination, or withdrawn or rejected) in this other Member State.

For both take-back requests and take-charge requests (incoming or outgoing), the requesting Member State must provide the requested Member State with formal proof or circumstantial evidence based either on EURODAC data or other relevant sources of information.

In the event of a take-charge request, the requested Member State must give a decision within 2 months of receiving the request (up to 3 months for a complex request). For a take-back request, the time frame for giving a decision is 1 month, and the time frame is only 2 weeks if the request is based on EURODAC data. If the requested Member State fails to act within the stipulated time frame, it is obliged to take charge or take back the non-EU citizen concerned. This includes the obligation to provide proper arrangements for arrival.

Decisions on take-charge or take-back requests can be either accepted or refused. The outcome of a request can also result in a unilateral decision (see definition below). Because some unilateral decisions, like the sovereignty clause, can take place at any moment of the Dublin procedure, the total number of Dublin decisions and unilateral decisions are not equal to the total number of requests. In the event of a negative decision, a re-examination request can be addressed to the same Member State within 3 weeks following the receipt of the first negative reply. It should be pointed out that, if the re-examination request is accepted, the reason invoked in the reply can differ from the reason invoked in the request. Data on Dublin requests are then updated based on the latest invoked reason.

An accepted Dublin request should ordinarily lead to a transfer of the asylum applicant from the requesting Member State to the requested Member State. The Eurostat data collection provides statistics on the number of transfers that actually took place and the number of pending transfers at the end of the reference period. A transfer can also be finally cancelled for the following reasons:

- the application of the sovereignty clause;

- the impossibility of transferring an asylum applicant because of the risk of inhuman or degrading treatment in the receiving Member State;

- the transfer was not carried out within set time limits.

Methodological aspects in asylum statistics

Annual aggregate of the number of asylum applicants

Annual statistics on the number of asylum applicants are compiled from the aggregation of reported monthly data. Since an asylum applicant can lodge several asylum applications in the same Member State during different months of a given year, annual data on the number of asylum applicants in a Member State possibly include multiple counting and could be overestimated. On the annual number of first-time asylum applicants in a Member State, the aggregation of monthly data does not lead to multiple counting since an asylum applicant can only lodge a first-time application once in a given Member State. It must also be added that, when a Member State provides some revised monthly data, the annual aggregate is also revised accordingly.

Consolidated EU aggregate

When aggregating the number of first-time asylum applicants at EU level, the number of asylum seekers who lodged an asylum application in several different Member States during the reference period should ordinarily be counted only once to avoid over-estimation. However, Eurostat does not collect the information related to previous applications lodged by asylum seekers over the years.

For the time being, the only available information about multiple applications comes from Dublin statistics, which can provide an estimate of the potential statistical bias caused by double-counting. For example, both the number of Dublin transfers based on take-charge requests and the number of take-back requests related to asylum applicants having lodged an application in the requesting country could theoretically correspond to multiple applications. However, even if this information is not complete and even if the reference period can differ (in particular for high-frequency data), summing up those take-charge and take-back requests gives a rough estimate of the possible maximum bias. It is also important to stress that it is possible for multiple applications to not be subject to a Dublin request, since a Member State can decide unilaterally to take responsibility for an asylum applicant even if he/she already lodged an application in another Member State. The maximum number of those later cases should ordinarily correspond to the recorded number of Dublin unilateral decisions based on the application of the discretionary clause. Based on the available information, Eurostat estimated the maximum number of double-counting of asylum applicants at EU level to be 625 000 over the 2015-2019 period, which corresponds to about 14 % of the recorded number of asylum applicants during this period.

Distinction between first-instance decision and final decision

Because of the diversity of administrative and judicial procedures for issuing a decision in the Member States, the distinction between a first-instance decision and a final decision taken on appeal or review in asylum statistics could be subject to interpretation. In particular, this distinction applies when the same judicial body or authority is in charge of reviewing in appeal its first decision.

Another issue arises that concerns the exact determination of the last stage of appeal, since a decision taken in appeal can very often be subject to a subsequent appeal. Statistical recording of a final decision therefore faces uncertainty about the definitive character of a final decision. Practices in several Member States consist in setting a time limit for considering a decision as final.

Eurostat is still working with Member States on possible ways to better harmonise the concepts used for defining final decisions taken on appeal or review.

Recognition rate

For the time being, two types of recognition rates are calculated by Eurostat:

- the first-instance recognition rate, which is equal to the number of positive first decisions divided by the total number of first decisions;

- the final-decision recognition rate, which is equal to the number of positive final decisions divided by the number of positive and negative final decisions.

Based on the statistics collected by Eurostat, it is not possible to directly build an aggregated recognition rate taking into account first and final decisions. For example, if one divides the total number of positive decisions (first and final) by the total number of decisions (first and final), it would result in an underestimated rate, since the denominator will be overestimated by including asylum applicants that were the subject of a first and a final decision during the same reference period.

Dividing the total number of positive decisions (first and final) by the number of first decisions during a given reference period also leads to a possibly biased recognition rate. This is because: (i) the denominator would not include asylum applicants who received a first decision during previous reference periods, but who were the object of a final decision during the current reference period; and (ii) the numerator would not include appealing applicants during the current reference period but who were still waiting for a final decision at the end of the period. Nevertheless, since it would be possible to have compensation between the numerator and the denominator, the ratio between the total number of positive decisions and the total number of first decisions for a given reference period is a more accurate estimation of a global recognition rate. This is true even if this accuracy can be severely endangered when the number of asylum decisions fluctuates greatly from one year to another.

Eurostat is currently investigating other estimation methods to provide a unique indicator as well as an assessment of its accuracy.

Link between asylum statistics and residence-permit statistics

First residence permits issued for refugee, subsidiary-protection or humanitarian reasons

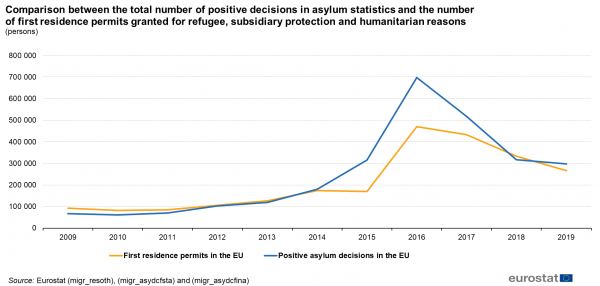

Residence-permit statistics include data on the number of non-EU nationals granted a first residence permit for refugee, subsidiary-protection or humanitarian-protection reasons. When comparing residence-permit data with the total number of beneficiaries of protection (first and final positive decisions and resettled persons) recorded in asylum statistics (see Figure 4 below), some discrepancies can nevertheless be observed. These discrepancies can be observed despite a correlated development over the 2009-2019 period. The main theoretical reasons which could explain this discrepancy are: (i) the time lag between a positive decision and the actual delivery of a residence permit; (ii) the fact that beneficiaries of international protection are not required to have a residence permit; and (iii) the possibility that a non-EU national has already received a residence permit before receiving a positive asylum decision. Those three reasons can mean that fewer first residence permits are recorded than the total number of beneficiaries of protection in the EU.

Figure 4: Comparison between the total number of positive decisions in asylum statistics and the number of first residence permits granted for refugee, subsidiary protection and humanitarian reasons (persons)

Source: Eurostat (migr_resoth), (migr_asydcfsta) and (migr_asydcfina)

Between 2009 and 2019, this positive bias amounted to 403 241, which corresponds to 14.7 % of the total number of beneficiaries of international protection recorded in the EU during this period. Nevertheless, this positive bias does not appear stable over time. Figure 4 shows a significant positive bias over the 2015-2017 period, whereas this bias is either close to zero or negative the rest of the time.

Valid residence permits at the end of the year issued for refugee and subsidiary-protection reasons

Residence-permit statistics provide an indicator of the stock of non-EU nationals at the end of the year holding a residence permit issued for refugee or subsidiary-protection reasons. When comparing the yearly change in residence-permit statistics with the asylum positive decisions granting refugee or subsidiary-protection status over the 2011-2019 period (see Figure 5 below), it is evident that the total observed changes in the stock of residence permits account for 68.0 % of the recorded number of corresponding asylum positive decisions. If part of this difference can theoretically be explained by the number of persons changing residence status or leaving the country, this difference most likely reflects a lack of consistency between recorded residence permits and asylum statistics.

Figure 5: Comparison between the yearly change in the stock of residence permits and the number of positive asylum decisions (refugee status and subsidiary protection) (persons)

Source: Eurostat (migr_resvalid), (migr_asydcfsta) and (migr_asydcfina)

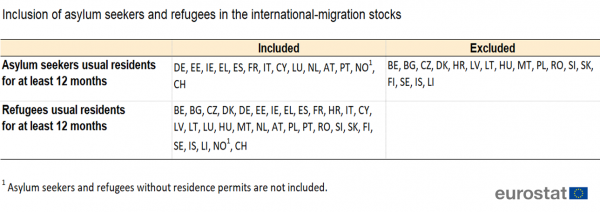

Link between asylum statistics and international-migration statistics

As can be seen in Table 4, refugees (beneficiaries of international protection) considered as usual residents are included in international-migration statistics (IM statistics) on the stock of migrants, whereas the treatment of asylum seekers can differ from one country to another.

Table 4: Inclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in the international-migration stocks

See here for explanation of country codes

Link between asylum statistics and enforcement-immigration-law (EIL) statistics

Asylum seekers could be in one of the following situations before they lodge an application.

- They can be found to be illegally present on the territory of a Member State.

- They can be found to have illegally crossed the border of a Member State.

Rejected asylum seekers could also be in one of the following situations.

- They can be found to be illegally present on the territory of a Member State.

- They can be ordered to leave the territory of a Member State.

- They can be transferred non-EU citizens.

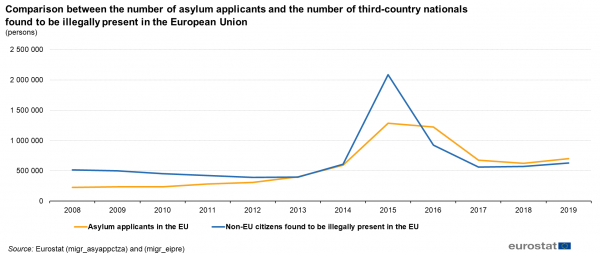

Therefore, there is a significant overlap between the statistical population covered by asylum statistics and the statistical population covered by EIL statistics. This overlap must be kept in mind when analysing asylum data and managed-migration data. As an example, Figure 6 below shows the trend in the number of asylum applicants and the number of non-EU citizens found to be illegally present on the Member States’ territory. The trend lines in the two curves suggest these two groups are correlated, and they seem to indicate that a significant share of asylum applicants is a sub-population of the non-EU nationals found to be illegally present in a Member State.

Figure 6: Comparison between the number of asylum applicants and the number of third-country nationals found to be illegally present in the European Union (persons)

Source: Eurostat (migr_asyappctza) and (migr_eipre)

This correlation observed at EU level is not always present at individual Member-State level and depends on the Member State in question. For example, the relationship between asylum data and EIL data is more visible in Germany, Hungary, Sweden or France, than in Belgium, Greece, Spain or Italy. This difference can be explained by several factors, the three most significant of which are set out in the bullet points below.

- Non-EU nationals found to be illegally present in a Member State can lodge an asylum application only in another Member State.

- There are different administrative/statistical practices for recording the legal status of asylum seekers. For example, once an asylum seeker lodges his or her application, she/he receives a temporary authorisation to stay in the Member State, but previous possible illegal presence of this asylum may or may not be recorded in EIL data depending on the Member State.

- There could be a delay between the recording of an asylum application and the detection of a non-EU national as being illegal.

Methodological aspects in Dublin statistics

Asymmetries

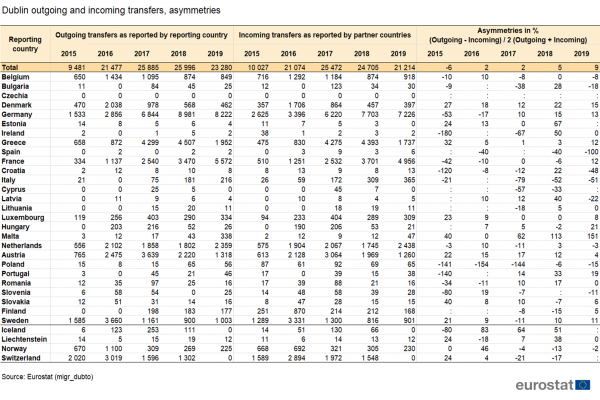

For most of the collected Dublin statistics, data are available for outgoing and incoming requests. Ordinarily, ‘mirror flows’ should show the same result. This means, for example, that the total number of outgoing requests addressed to a Member State should theoretically equal the total number of incoming requests received by this Member State. In practice, when comparing reported outgoing and incoming data, some significant discrepancies, called asymmetries, are observed because of practical and methodological reasons. Among the possible reasons for those asymmetries are: (i) time lags in recording; (ii) the use of different reference periods for recording the same flow; (iii) different numbers of asylum seekers linked to the same request; (iv) asylum seekers absconding; or (v) the treatment of requests related to unilateral decisions. Eurostat is still carrying out investigations, particularly at bilateral level between Member States, to continue to explain and reduce these asymmetries. Tables 5a to 5c [6] present the level of asymmetries as a percentage of the average observed flows (reporting and partner counterpart) over the 2015-2019 period for flows related to: (i) the number of requests; (ii) the number of decisions; and (iii) the number of transfers.

For example, Table 5a shows that the level of asymmetries for Dublin requests has tended to decrease since 2017. Nevertheless, there were significant asymmetries recorded in 2019 for Germany (and to a lesser extent France and Italy), and work is ongoing to better understand the origins of these asymmetries and to reduce them as much as possible.

On the asymmetries recorded for the number of decisions in response to a Dublin request, Table 5b indicates that the absolute value of asymmetries at an aggregated level is comparable to the absolute value of asymmetries at an aggregated level observed for requests in Table 5a. Nevertheless, the distribution by countries of the recorded asymmetries for the number of decisions appears to be more diverse, as shown by recorded data for Austria, Germany, France and Italy, as well as Switzerland. In terms of trends, the total asymmetries varied from one year to another over the 2015-2019 period, and seemed to cancel each other out when summed up over the 5 years.

For Dublin transfers presented in Table 5c, the magnitude and/or sign of the asymmetries varies greatly from one year to another and from one country to another (except in Austria and in Germany over the last 3 years). For the total asymmetries, a slight upward trend can be observed over the 2015-2019 period. Since an asylum seeker can abscond during his or her transfer, the difference between outgoing and incoming transfers is not always zero and should be positive.

Unilateral decisions

According to the available data over the 2015-2019 period, the interpretation of the methodology for recording Dublin unilateral decisions can differ from one Member State to another. Based on recent work by Eurostat in collaboration with the Member States, the main issues causing these differing interpretations have been identified. This will lead to an update of the current methodology to better harmonise future collection on those Dublin flows by the Member States.

Because currently available data on Dublin unilateral decisions are not yet harmonised, unilateral Dublin decisions should be analysed very cautiously and used only in connection with relevant metadata.

What questions can or cannot be answered with available asylum statistics and Dublin statistics?

How many asylum seekers are entering EU Member States each year?

The number of first-time asylum applicants recorded during the year provides a Member-State level answer to this question. At EU level, this indicator (arrived at by aggregating all the Member State data) may provide an overestimated figure because of the existence of multiple first-time applications in different Member States.

Asylum applicants by type, citizenship, age and sex - annual aggregated data

How many non-EU citizens enter EU Member States each year?

First-time asylum applicants constitute some of the non-EU citizens who enter the EU during a given year. To this number it is necessary to add the number of non-EU citizens entering either: (i) legally for other reasons; or (ii) illegally. Residence-permit (first-time permits) statistics and EIL statistics (detailing the number of non-EU nationals found to be illegally present) can provide some additional information. However, because of the overlap between these three statistical populations (first-time asylum applicants, applicants for first-time residence permits, and non-EU nationals found to be illegally present), asylum and managed-migration statistics cannot give a direct answer to this question. The best indicator for answering this question thus remains the number of non-EU citizens that migrated to the EU during the year. This information is included in the international-migration statistics [7] collected by Eurostat.

Immigration by age group, sex and citizenship

How many asylum seekers are granted protection?

The total number of first and final positive decisions can be used to answer this question.

First instance decisions on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual aggregated data (rounded)

Final decisions in appeal or review on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual data (rounded)

What kind of protection is granted to asylum seekers?

Statistics on decisions are broken down by type of granted status, indicating if an asylum seeker has been granted with refugee status, subsidiary-protection status, or humanitarian-protection status.

First instance decisions on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual aggregated data (rounded)

Final decisions in appeal or review on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual data (rounded)

What is the share of women and children in the total number of asylum seekers or beneficiaries of protection in the EU?

Because Eurostat asylum data are broken down by age and by sex, those ratios can be derived from Eurostat’s database.

First instance decisions on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual aggregated data (rounded)

Final decisions in appeal or review on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual data (rounded)

From what countries do asylum seekers and beneficiaries of protection in the EU come from?

The breakdown by citizenship of asylum seekers and beneficiaries of protection provides all the necessary information to answer this question.

Asylum applicants by type, citizenship, age and sex - annual aggregated data

First instance decisions on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual aggregated data (rounded)

Final decisions in appeal or review on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual data (rounded)

How many asylum seekers are the object of a Dublin procedure between Member States to determine the responsible Member State?

The number of Dublin requests provides an indicator to answer this question. Nevertheless, users must take into account the fact that the same asylum seeker can be the object of several requests and that there are asymmetries between outgoing and incoming requests.

Incoming 'Dublin' requests by submitting country (PARTNER), type of request and legal provision

Outgoing 'Dublin' requests by receiving country (PARTNER), type of request and legal provision

How many asylum seekers are transferred from one Member State to another as a consequence of the Dublin procedure?

The number of Dublin transfers is available and gives a good answer to this question.

Incoming 'Dublin' requests by submitting country (PARTNER), type of request and legal provision

Outgoing 'Dublin' requests by receiving country (PARTNER), type of request and legal provision

What happens with rejected asylum seekers?

Eurostat does not collect data directly answering this question. EIL statistics can nevertheless provide some proxy indicators (non-EU nationals ordered to leave; non-EU nationals returned following an order to leave; non-EU nationals who have left the territory; or non-EU nationals who have left the territory to go to another non-EU country) since EIL statistical populations must include rejected asylum seekers.

Third country nationals ordered to leave - annual data (rounded)

Third country nationals returned following an order to leave - annual data (rounded)

How many non-EU citizens are granted protection each year in the EU?

This question can be answered by adding the total number of positive decisions and the total number of resettled persons. Residence-permit statistics can also provide some indications on this, but these statistics are less accurate and are most often underestimated.

First instance decisions on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual aggregated data (rounded)

Final decisions in appeal or review on applications by citizenship, age and sex - annual data (rounded)

Resettled persons by age, sex and citizenship - annual data (rounded)

How many asylum seekers are unaccompanied minors?

Eurostat’s dedicated table on unaccompanied minors who apply for asylum provides all the necessary information to answer this question.

How many asylum seekers are there in the EU?

The number of pending asylum applications gives the answer to this question and is updated monthly.

How many non-EU citizens are in the EU with a refugee status or another type of international protection?

Asylum statistics do not provide data that can answer this question. Residence-permit statistics give the total number of valid residence permits issued for refugee or subsidiary-protection status, but these statistics must be used cautiously when comparing them with the flows recorded in asylum statistics.

All valid permits by age, sex and citizenship on 31 December of each year

Policy context

The collected asylum statistics and Dublin statistics are of use for following a number of policy areas in the field of migration, which are generally under the auspices of the Directorate-General Migration and Home Affairs (DG HOME).

The Common European Asylum System (CEAS)

The 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the status of refugees (as amended by the 1967 New York Protocol) has, for around 70 years, defined who is a refugee. The Geneva Convention has also laid down a common approach towards refugees that has been one of the cornerstones for the development of a common asylum system within the EU. Since 1999, the EU has worked towards creating a common European asylum regime in accordance with the Geneva Convention and other applicable international instruments.

The Hague programme was adopted by heads of state and government on 5 November 2004. It promotes the idea of a CEAS. In particular, it raises the challenge of setting common procedures and a uniform status across the EU for those granted asylum or subsidiary protection. The European Commission’s policy plan on asylum (COM(2008) 360 final) was presented in June 2008, and included three pillars to underpin the development of the CEAS:

- greater harmonisation in standards of protection by further aligning EU Member States’ asylum legislation;

- effective and well-supported practical cooperation;

- more solidarity and a greater sense of responsibility among EU Member States, and between the EU and the rest of the world.

With this in mind, the European Commission in 2009 proposed to set up a European asylum support office (EASO). After 10 years of operation, EASO was transformed into the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) through Regulation (EU) 2021/2303 which entered into force on 19 January 2022. The EASO/EUAA has been set up and supports EU Member States in their efforts to implement a more consistent and fair asylum policy. It also provides technical and operational support to Member States facing particular pressures (in other words, Member States receiving large numbers of asylum applicants). The EASO/EUAA works with the European Commission and the UNHCR.

In May 2010, the European Commission presented an action plan for unaccompanied minors (COM(2010) 213 final), who are regarded as the most exposed and vulnerable victims of migration. This plan aims to set up a coordinated approach across the EU, and commits all EU Member States to grant high standards of reception, protection and integration for unaccompanied minors. As a complement to this action plan, the European Migration Network - EMN has produced a comprehensive EU study on reception policies, as well as return and integration arrangements for unaccompanied minors.

A number of directives in this area have been developed. The four main legal instruments on asylum are:

- the Qualification Directive 2011/95/EU on standards: (i) for the qualification of non-EU nationals and stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection; (ii) for a uniform status for refugees; or (iii) for persons eligible for subsidiary protection;

- the Procedures Directive 2013/32/EU on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection;

- the Conditions Directive 2013/33/EU laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection;

- the Dublin Regulation (EU) 604/2013 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the EU Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a non-EU national (national of a non-member country) or stateless person.

EU operational and financial support has been instrumental in helping Member States to address the migration challenge. In particular, the European Commission offers Member States continued financial support under the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF). The AMIF has effectively and successfully supported the EU’s common response to the migration crisis, while also providing a sign of solidarity to the Member States on the frontline.

In April 2016, the European Commission adopted a communication (COM(2016) 197 final) launching the process for a reform of the CEAS. This reform included suggestions on: (i) options for a fair and sustainable system for allocating asylum applicants among EU Member States; (ii) a further harmonisation of asylum procedures and standards to create a level playing field across the EU and thus reduce ‘pull’ factors inducing irregular ‘secondary’ movements (i.e. when an asylum seeker arrives in Member State A, but then travels to Member State B to claim asylum); and (iii) a strengthening of the mandate of the EASO.

In May 2016, the European Commission presented a first package of reforms, including proposals for: (i) establishing a sustainable and fair Dublin system (COM(2016) 270 final); (ii) strengthening the EURODAC system (COM(2016) 272 final); and (iii) establishing a European agency for asylum (COM(2016) 271 final).

In July 2016, the European Commission put forward a second set of proposals for the reform of the CEAS. The proposals included: (i) creating a resettlement framework for the EU (COM(2016) 468 final); (ii) creating a common procedure for international protection (COM(2016) 467 final); and (iii) recasting the legislation on the standards for receiving applicants for international protection (COM(2016) 465 final).

In March 2019, the European Commission reported on the progress made over the past 4 years in asylum management, and set out the measures still required to address immediate and future migration challenges (COM/2019/126 final).

The Pact on Migration and Asylum was adopted by the European Parliament in April 2024 and by the Council in May 2024. This Pact provides a comprehensive approach that delivers a common European response to migration. It allows the EU to manage migration in a fair and sustainable way, ensuring solidarity between countries while also providing certainty and clarity for people arriving in the EU and protecting their fundamental rights. The Pact on Migration and Asylum will ensure that countries share the effort responsibly, showing solidarity with the ones that protect our external borders and with those facing particular migratory pressure, while preventing irregular migration to the EU. The Pact also gives the EU and its countries the tools to react rapidly in situations of crisis, when countries are faced with large numbers of arrivals or when a third-country or non-State entity tries to instrumentalise migrants in order to destabilise our Union.

The Dublin Regulation

The Dublin Regulation (developed from the original Dublin Convention) lays down rules on which EU Member State is responsible for examining an asylum application. Regulation (EC) 2003/343 (known as Dublin II) replaced the 1990 Dublin Convention (the 1990 convention was the first legal instrument to lay down criteria on responsibility for processing an individual asylum seeker’s asylum application). Dublin II remained valid until 1 January 2014, when Regulation (EU) No 604/2013 (known as Dublin III), which was adopted on 26 June 2013, entered into force. All Member States apply the Dublin Regulation, as do the EFTA countries.

The Dublin procedure establishes the principle that only one EU Member State is responsible for examining an asylum application. The objective is to avoid asylum seekers being sent from one country to another and also to prevent abuse of the system by the submission of several applications for asylum by one person. The criteria for establishing responsibility range, in hierarchical order, from family considerations, to recent possession of a visa or residence permit in a Member State, to whether the applicant has entered the EU irregularly or regularly.

In April 2016, the European Commission presented a communication, Towards a reform of the Common European Asylum System and enhancing legal avenues to Europe (COM(2016) 197 final). This was followed in May and July 2016 by two packages of proposals for reforming the CEAS. Part of the first package was a proposal for a reform of the Dublin Regulation (COM(2016) 0270 final/2).

EU legal references

- Regulation (EC) No 862/2007 on Community statistics on migration and international protection.

- the Qualification Directive on standards: (i) for the qualification of non-EU nationals and stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection; (ii) for a uniform status for refugees; or (iii) for persons eligible for subsidiary protection.

- the Asylum Procedures Directive on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection.

- the Reception Conditions Directive laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection.

- the Dublin Regulation establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a non-EU national or stateless person.

- the EURODAC Regulation on the access to the EU fingerprint database record of the asylum seeker.

Source data for tables and graphs

Footnotes

- The Qualification Directive on standards for the qualification of non-EU nationals and stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, for a uniform status for refugees or for persons eligible for subsidiary protection.

The Asylum Procedures Directive on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection.

The Reception Conditions Directive laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection.

The Dublin Regulation establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a non-EU national or stateless person.

The EURODAC Regulation on access to the EU fingerprint database record of the asylum seeker. ↑ - Since the same asylum applicant can theoretically lodge several asylum applications in the same Member State during different reference periods, aggregation of monthly data can lead to overestimates of the annual number of asylum applicants. ↑

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/migration-asylum/asylum ↑

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1414508297956&uri=CELEX:32007R0862 ↑

- EURODAC is an IT system that collects, distributes and compares fingerprints of asylum seekers aged older than 14. EURODAC assists in determining which EU Member State is to be responsible for examining an asylum application lodged in an EU Member State by a non-EU citizen. ↑

- Figures presented in Tables 5a to 5c only include data when they are available for both reporting and partner countries. ↑

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/migration-asylum/international-migration-citizenship ↑