Data extracted in February 2025

Planned article update: 6 March 2026

Highlights

In 2024, over a third of national parliament members in the EU were women (33.4%), up from 27.8% in 2014.

Between 2013 and 2023, the employment gap narrowed, but women remained more likely to work part-time (+20.2 pp relative to men), with nearly a third citing caregiving as the main reason.

In 2023, the severe material and social deprivation rate declined for both men and women compared with 2015, with the men’s rate dropping from 9.1% to 6.5% and the women’s rate from 10.2% to 7.2%.

This article examines the evolution of gender equality within the European Union (EU) over the past decade, drawing on Eurostat data to highlight key trends and progress. Progress is evident over the past 10 years, with an increased female representation in national parliaments, a narrowing employment gap, and a reduction in the gender pay gap. However, women still represent only 17.9% of graduates in STEM and life sciences, compared to 42.4% of men. In the workforce, although the part-time employment gap has decreased, caregiving continues to be a primary reason for nearly a third of women working part-time. Broader measures of well-being also reveal that women continue to experience slightly higher economic vulnerability.

Women in parliament

In the EU, the average proportion of women in parliament reached 33.4% in 2024, reflecting an increase from 27.8% in 2014.

In 2024, 13 EU countries were above the EU average for female parliamentary representation, namely Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Spain, Belgium, Austria, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Portugal, Luxembourg, Croatia and Italy. Latvia, Slovenia and Lithuania closely followed. While the remaining countries were further from the EU average to varying degrees, most had shown improvements since 2014.

The countries with the largest increases in female parliamentary representation include Malta, Latvia, Austria, France, Estonia, Croatia, Ireland, Romania and Poland. In contrast, the countries with the smallest increases include Slovenia, Belgium, Greece, Sweden and Slovakia. It is important to note that many of these countries already had relatively high levels of female representation in 2014, which partly explains why their increases have been more modest compared to other nations. Cyprus maintained the same number of parliamentary seats for female representation, while Germany was the only country to record a decrease, with fewer seats for women in 2024 than in 2014.

Source: European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), (sdg_05_50)

Gender balance in higher education degrees

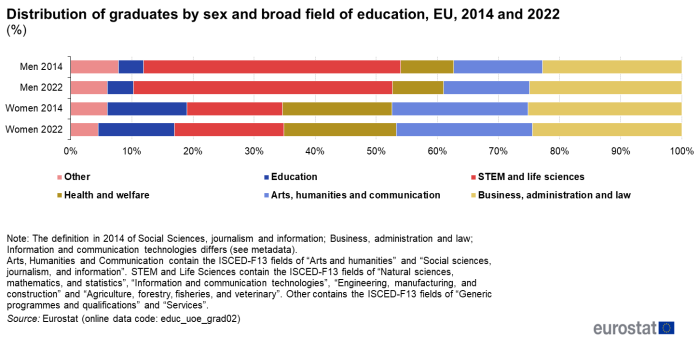

At EU level, education paths differ significantly between women and men. In 2022, women were predominantly represented in arts and humanities, and health and welfare fields (40.7%), while 42.4% of men graduated in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and life sciences.[1]

Between 2014 and 2022, the share of women in STEM and life sciences, a field traditionally dominated by men, grew from 15.7% to 17.9%, while their presence in business, administration, and law decreased from 25.2% to 24.4%. Meanwhile, the share of men in business, administration, and law rose from 22.8% to 25.0%. These shifts, though modest, indicate a gradual progress toward a more balanced distribution.

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_grad02)

Gender gap by type of employment

The gender employment gap by type of employment has narrowed over time.

In the EU, the overall employment gap declined from 11.2% in 2013 to 10.2% in 2023, showing an improved gender parity in the workforce. The share of women working part-time remained higher than the share of men, but the part-time employment gap decreased from -23.9% in 2013 to -20.2% in 2023. The gender underemployment gap showed an improvement, shrinking from -3.9% to -2.1% over the period.

Main reason for working part-time

While caregiving remains a key reason for part-time work among women, education and training becomes the 2nd most important reason for men.

As part-time employment continues to show the largest gender gap, this chart examines the main reasons for men and women to have worked part-time in 2023 compared with 2013.

In 2023, both men and women reported a notable shift in their reasons for part-time work.[2] The share citing ’no full-time job found’ declined for men from 42.6% to 26.0% and for women from 28.9% to 18.2%. Meanwhile, ’education or training’ increased for men from 13.9% to 19.3% and for women from 5.0% to 8.0%. Additionally, caregiving increased as the main reason for working part-time for women, reaching 27.2% in 2023. Its significance grew also for men, rising from 3.7% to 6.8%.

Gender pay gap

The gender pay gap saw a decreasing overall trend, with the EU-average falling from 16% in 2013 to 12% in 2023.

In 2023, 24 of the 27 EU countries saw improvements in the unadjusted gender pay gap compared with 2013, with reductions ranging from 0.3 percentage points (pp) in Croatia to 12.9 pp in Estonia. Notably, Estonia showed the largest improvement from 29.8% in 2013 to 16.9% in 2023. Spain followed with a reduction of 8.6 pp (from 17.8% in 2013 to 9.2% in 2023), and Luxembourg by 7.1 pp (from 6.2% in 2013 to -0.9% in 2023). In Luxembourg, the gap reversed so that, on average, women earned 0.9% more than men. Overall, the EU average declined by 4 pp, reflecting widespread progress toward more balanced hourly earnings for female and male employees on average.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_05_20)

Male to female ratio among information and communication technology (ICT) specialists

The male to female ratio of ICT specialists[3] decreased by 17% over a decade.

As progress is made in closing the gender pay gap, it can also be insightful to examine the gender disparities in the labour market, such as the gender ratio among employed ICT specialists.

Between 2013 and 2023, the number of male ICT specialists increased from 5.13 million to 7.89 million, while the number of female ICT specialists nearly doubled from 1.02 million to 1.90 million among the EU countries. As a result, the male-to-female ratio dropped from 5.00 to 4.15 with a steady decline since 2014, showing a steady shift towards a more balanced representation, though men still significantly outnumber women in the field.

Severe material and social deprivation

Overall, between 2015 and 2023, the severe material and social deprivation steadily declined for both men and women, though women consistently reported slightly higher shares than men.

Beyond labour market indicators, it is also essential to consider living conditions, such as severe material and social deprivation.

The severe material and social deprivation rate declined for both men and women between 2015 and 2021, with a slight increase in 2022-2023. The rate for men dropped from 9.1% in 2015 to 6.5% in 2023, while the rate for women decreased from 10.2% to 7.2% during the same period. Although shares for women remain slightly higher, both men and women show notable improvements over the period, with men reducing their rate by 2.6 pp and women by 3.0 pp.

Ability to spend a small amount of money on themselves

Between 2015 and 2023, both men and women saw a steady increase in their ability to afford small personal expenses each week, with women experiencing the largest increase in pp.

Between 2015 and 2023, the share of men who could not afford to spend a small amount of money on themselves each week decreased from 14.4% to 10.3%, while for women, it fell from 17.7% to 12.8%. Despite the rate for women remaining higher throughout, both men and women recorded notable improvements, with the rate for men decreasing by 4.1 pp and for women by 4.9 pp.

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdsd11)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The data used in this article is derived from the Eurostat database which includes indicators from the European Survey on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) and the European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), as well as other sources, such as the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE).

- The women’s parliamentary representation indicator is derived from the seats held by women in national parliaments indicator and it measures the proportion of women in national parliaments. The data stems from the Gender Statistics Database of EIGE.

- The comparison of women and men graduates by field of education indicator is derived from the number of graduates by education level, programme orientation, sex and field of education. The source of the dataset is Eurostat.

- The gender gap by type of employment indicator measures the difference between the employment rates of men and women aged 20 to 64 in different working arrangements, overall employment, part-time employment and underemployment. The original indicator shows 4 groups of people: employed persons working full time, employed persons working part time, employed persons with temporary contract and underemployed persons working part time. The indicator is based on the EU-LFS.

- The main reason for working part-time indicator shows the distribution by sex, age and year of the main reason for working part-time. The indicator is based on the EU-LFS.

- The gender gap in hourly earnings indicator is derived from the gender pay gap in unadjusted form indicator, which measures the difference between average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees and of female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees.

- The gender ratio of employed ICT specialists indicator stems from the original indicator, employed ICT specialists by sex count.

- The severe material and social deprivation rate indicator is an EU-SILC indicator that shows an enforced lack of necessary and desirable items to lead an adequate life.

- Finally, the indicator for persons who cannot afford to spend a small amount of money each week on themselves is derived from the EU-SILC and is defined as the proportion of the population experiencing an enforced lack of weekly personal expenses.

Context

According to the European Commission's Political Guidelines 2024-2029, gender equality is a key priority for the Commission 2024-2029. Such guidelines emphasise the need to address the persistent gender disparities across all spheres of society, from the labour market and political representation to education and social services. The Commission is committed to implementing policies that empower women, promote equal opportunities, and enhance participation in leadership roles. By supporting initiatives aimed at closing the gender pay gap, increasing female representation in decision-making bodies, and fostering inclusive workplace practices, the Commission seeks to build a more balanced and resilient society.

By prioritising gender equality, the Commission seeks to improve the quality of life for European citizens, promote social cohesion and contribute to a more sustainable and inclusive future for all.

Footnotes

- The indicator for comparison of women and men tertiary graduates includes the ISCED-F13 fields categories F01 Education; F04 Business, administration and law; F09 Health and welfare, as well as the furtherly aggregated categories: Arts, humanities and communication, which includes the ISCED-F13 fields F02 Arts and humanities and F03 Social Sciences, journalism and information. The STEM and life sciences category includes F05 Natural sciences, mathematics and statistics; F06 Information and communication technologies; F07 Engineering, manufacturing and construction and F08 Agriculture, forestry, fisheries and veterinary. Finally, the category Other is a residual and includes all other fields not mentioned in the other categories. ↑

- The main reasons for working part time include education or training; no full-time job found; caregiving and other reasons, which contain other family or personal reasons; other family reasons; other illness or disability and other reason. ↑

- Information and communication technology (ICT) specialists are defined as workers who have the ability to develop, operate and maintain ICT systems and for whom ICT constitute the main part of their job. ↑