Archive:Healthcare expenditure statistics

Data extracted in April 2021.

Planned article update: May 2021.

Highlights

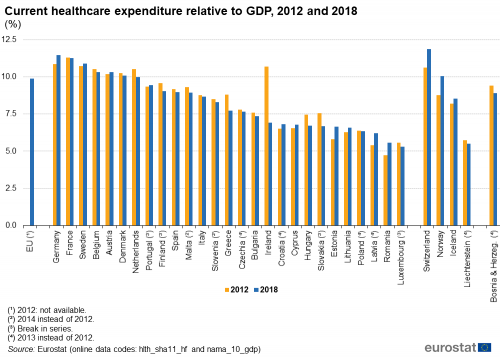

Among the EU Member States, Germany, France and Sweden had the highest healthcare expenditure relative to GDP in 2018 (between 10.9% and 11.5%).

Among the EU Member States, the largest expansions in current healthcare expenditure per inhabitant between 2012 and 2018 were recorded in Romania and the Baltic Member States.

Current healthcare expenditure relative to GDP, 2017

This article presents key statistics on expenditure and financing aspects of healthcare in the European Union (EU). Healthcare systems are organised and financed in different ways across the EU Member States, but universal access to quality healthcare, at an affordable cost to both individuals and society at large, is widely regarded as a basic need; moreover, this is one of the common values and principles of EU health systems.

Statistics on healthcare expenditure and financing may be used to evaluate how a healthcare system responds to the challenge of universal access to quality healthcare, through measuring financial resources within the healthcare sector and the allocation of these resources between healthcare activities (for example, preventive and curative care) or groups of healthcare providers (for example, hospitals and ambulatory centres).

This article forms part of an online publication on Health in the European Union.

Full article

Healthcare expenditure

Germany, France and Sweden had the highest current healthcare expenditure relative to GDP in 2018

The level of current healthcare expenditure in Germany was EUR 384 billion in 2018 — the highest value among the EU Member States. France recorded the second highest level of current healthcare expenditure (EUR 266 billion), followed by Italy (EUR 153 billion) and Spain (EUR 108 billion).

Current healthcare expenditure in Germany and France was equivalent to 11.5 and 11.3 % of gross domestic product (GDP), more than in any other EU Member State — see Table 1. The next highest ratios were in Sweden (10.9 %), Austria and Belgium (10.3 %), Denmark (10.1 %) and The Netherlands (10.0 %); none of the remaining EU Member States recorded double-digit ratios. Note that current healthcare expenditure in Switzerland was equivalent to 11.9 % of GDP, higher than the ratio in Germany, while this ratio reached 10.1 % in Norway. By contrast, current healthcare expenditure accounted for less than 7.5 % of GDP in 12 Member States, with Luxembourg recording the lowest ratio (5.3 %).

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf), (demo_gind) and (nama_10_gdp)

Relative to population size and in euro terms, current healthcare expenditure was highest among the EU Member States in Denmark (EUR 5 256 per inhabitant), Luxembourg (EUR 5 221 per inhabitant) and Sweden (EUR 5 041 per inhabitant) in 2018. It is interesting to note that Luxembourg had the second highest ratio per inhabitant given that it had the lowest ratio of healthcare expenditure to GDP, reflecting the high level of GDP in Luxembourg. A significant proportion of workers in Luxembourg are cross-border workers and live outside the country; note that, as non-residents, the expenditure on their healthcare is not included in Luxembourg’s health accounts while their economic activity does contribute to Luxembourg’s GDP. All four EFTA countries included in Table 1 — Liechtenstein, Switzerland, Norway and Iceland — each reported higher levels of healthcare expenditure per inhabitant than in any of the Member States. Following on from Denmark, Luxembourg and Sweden, a group of four Member States — Germany, Ireland, Austria and the Netherlands — recorded current healthcare expenditure between EUR 4 480 and 4 627 per inhabitant. In turn, these were followed at some distance by another group — Belgium, France and Finland — with ratios in the range of EUR 3 829 to 4 150 per inhabitant. There was then a relatively large gap to Italy (EUR 2 534 per inhabitant), Spain (EUR 2 310) and Malta (EUR 2 290). All of the remaining 14 Member States recorded average expenditure of EUR 1 877 per inhabitant or less in 2018, with six of these recording an average spend on healthcare below EUR 1 000 per inhabitant. The lowest levels of average expenditure per inhabitant were in Bulgaria (EUR 587) and Romania (EUR 584). As such, the ratio between the highest (Denmark) and lowest (Romania) levels of expenditure per inhabitant was 9.0 : 1.

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf) and (demo_gind)

These disparities were less apparent when expenditure was expressed in purchasing power standards (PPS); this measure adjusts for differences in price levels between the EU Member States. Germany (4 473 PPS per inhabitant), Austria (3 980 PPS per inhabitant), the Netherlands (3 907 PPS per inhabitant) and Sweden (3 905 PPS per inhabitant) recorded the highest ratios of healthcare expenditure per inhabitant in PPS terms. Bulgaria (1 269 PPS per inhabitant) and Romania (1 212 PPS per inhabitant) had the lowest ratio. As such, by taking account of price level differences, the ratio between the highest (Germany) and lowest (Romania) levels of healthcare expenditure per inhabitant was considerably narrower than the equivalent ratio in euro terms mentioned above, as it was 3.7 : 1.

Developments over time

Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3 highlight the developments in the level of healthcare expenditure in recent years, focusing on a comparison between 2012 and 2018. Note that the analyses are presented in current price terms and so reflect price changes (inflation and deflation) as well as real changes in expenditure.

Among the 21 EU Member States for which 2012 and 2018 data are available, all except Greece recorded higher healthcare expenditure in 2018 than in 2012. The largest overall increase was observed in Romania, where expenditure in 2018 was 81.0 % higher than in 2012, an increase equivalent to an average of 11.6 % per year. As well as Romania, other EU Member States recorded overall increases of more than 20 %: Estonia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Luxembourg, Germany, Portugal, Austria and Hungary between 2012 and 2018 and Latvia, Malta, Czechia, Poland and Croatia for alternative years (comparing with years 2013 or 2014).

As well as being affected by price changes, comparisons of healthcare expenditure over time can also be influenced by demographic changes. Figure 2 shows the average healthcare expenditure per inhabitant in 2012 and 2018 (see footnotes under the figure for cases where alternative years have been used). Greece was the only country where a lower expenditure per inhabitant in 2018 than in 2012 was recorded (-12.8 %.). As for the rate of change based on overall expenditure, Romania recorded the largest increase, with average expenditure per inhabitant increasing by 86.5 %. Again, Estonia (up 66.1 %), Lithuania (51.2 %) and Bulgaria (34.5 %) recorded large increases in expenditure per inhabitant, as did Latvia (52.9 %, between 2013 and 2018).

(EUR)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf) and (demo_gind)

Figure 3 provides another analysis of the change in overall healthcare expenditure between 2012 and 2018, focusing on the ratio between this expenditure and GDP. Healthcare expenditure and GDP are both influenced by price changes and so, when combining the two indicators in a ratio, the impact of inflation may be cancelled out to some degree: this depends on the extent to which the price changes related to healthcare expenditure are similar to those experienced for the economy as a whole.

A total of 17 of the EU Member States reported a lower ratio of healthcare expenditure to GDP in 2018 than in 2012 (2013 or 2014 for some Member States), while the other 10 reported a higher ratio in 2018. By far the largest fall was in Ireland, where the ratio was 3.8 percentage points lower in 2018 (6.9 %) than it had been in 2012 (10.7 %). In the Member States where the ratio was higher in 2018 than it had been in 2012, the increase was 0.9 percentage points or less, with the largest increases in Estonia and Romania. Among the non-member countries shown in Figure 3, both Norway and Switzerland (up 1.3 percentage points) recorded larger increases in their healthcare expenditure relative to GDP.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf) and (nama_10_gdp)

Overview of healthcare financing, functions and providers

Healthcare expenditure can be analysed from three perspectives: the sources of financing; the healthcare functions that are financed; the providers of healthcare.

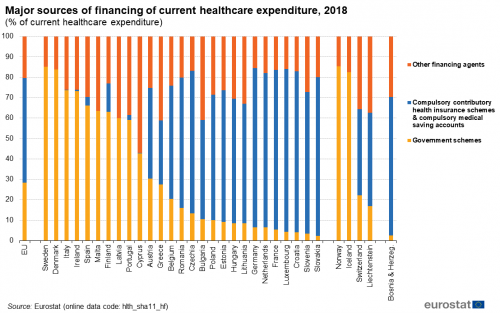

Table 3 identifies the largest sources of financing, functions and providers. Government schemes provided the financing for 28.3 % of all healthcare expenditure in the EU in 2018, while compulsory contributory health insurance schemes and compulsory medical saving accounts accounted for 51.3 %. As such, these two sources accounted for 79.6 % of all financing. More than half (53.4 %) of healthcare expenditure in the EU in 201 was for curative and rehabilitative care, while nearly one fifth (18.8 %) was for medical goods. Hospitals were the largest providers of healthcare in expenditure terms, accounting for more than one third (36.3 %) of all expenditure in the EU. Providers of ambulatory health care (25.5 %) and retailers and other providers of medical goods (17.6 %) were the second and third largest providers of healthcare in expenditure terms.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf), (hlth_sha11_hc) and (hlth_sha11_hp)

Table 4 shows how the expenditure for each of the largest sources of financing, functions and providers changed between 2012 and 2018. Data are available for 21 EU Member States.

Between 2012 and 2018, the largest increase in healthcare financing in five EU Member States (for example, in Romania and Belgium) was from government schemes while in eight more (for example, in Portugal) it was from compulsory schemes and saving accounts; consequently there were eight Member States (for example, Estonia) where expenditure from other financing schemes increased more than from these two large sources.

In terms of healthcare functions, in seven EU Member States (for example, in the Netherlands) the largest increase was for expenditure on curative and rehabilitative care, while in three others (for example, in Spain) expenditure increased most for medical goods. As such, in more than half of the Member States for which data are available (11 out of 21; for example, in Germany), the increase in expenditure on other functions was greater than for curative and rehabilitative care or for medical goods.

For healthcare providers, the largest increase in expenditure between 2012 and 2018 in nineEU Member States (for example, in Romania) was for hospitals, while in fivemore (for example, in France) it was for providers of ambulatory health care and in one (in Cypryus) it was for retailers and other providers of medical goods. In Sweden, the increase between 2012 and 2018 was quite similar for hospitals and ambulatory health care expenditures. Consequently, there were five Member States (for example, Estonia) where expenditure for other providers increased more than for these three large providers.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf), (hlth_sha11_hc) and (hlth_sha11_hp)

While Tables 3 and 4 offered an overview of the three perspectives (sources of financing, functions and providers), the remainder of this article looks at each of these perspectives in more detail.

Healthcare expenditure by financing scheme

Compulsory schemes and accounts financed more than half of healthcare expenditure in 14 EU Member States in 2018

Figure 4 provides a simplified analysis of healthcare expenditure by financing scheme, distinguishing: government schemes, compulsory contributory health insurance schemes and compulsory medical savings accounts (which are generally part of the social security system and are hereafter referred to as compulsory schemes/accounts), as well as all other financing agents. The share of government schemes and compulsory schemes/accounts in total current healthcare expenditure was in excess of 80.0 % in Sweden (where the highest share was recorded, at 85.1 %), Germany, Luxembourg, Denmark, Sweden, France, Czechia, Croatia and the Netherlands; it was also above 80.0 % in Norway (which reported a share that was above that registered in any of the EU Member States, at 85.3 %) and Iceland among the EFTA countries.

With the exception of Cyprus, the combined expenditure from government schemes and compulsory schemes/accounts in 2018 exceeded the expenditure from all other sources in each of the EU Member States, each of the EFTA countries and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In most of the EU Member States, either government schemes or compulsory schemes/accounts dominated: in nine Member States government schemes accounted for more than half of all expenditure and in 14 Member States compulsory schemes/accounts accounted for more than half of all expenditure. In Bulgaria, compulsory schemes/accounts registered a larger share than government schemes or other sources, but less than half of the total. In the remaining two Member States — Greece and Cyprus — other sources provided a greater share of financing than government schemes or compulsory schemes/accounts; however only in Cyprus did other sources provide a majority (57.0 %) of the financing.

Compulsory schemes/accounts accounted for three quarters or more of overall spending on healthcare in Luxembourg (79.7 %), Croatia (78.7 %), France (78.2 %), Germany (78.1 %), Slovakia (77.8 %) and the Netherlands (75.7 %) in 2018, but less than 5.0 % in Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Cyprus and Italy. It should be noted that compulsory schemes/accounts do not exist in Denmark, Latvia, Malta and Sweden and are therefore reported with 0 value (not existing). By contrast, Sweden (85.1 %) and Denmark (83.9 %) reported that government schemes accounted for more than four fifths of their expenditure on healthcare, while shares of between 65.0 % and 75.0 % were registered in Italy, Ireland and Spain.

(% of current healthcare expenditure)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf)

Table 5 provides a similar analysis of healthcare expenditure by financing scheme, but with more detail concerning other financing schemes.

The third largest source of healthcare funding was household out-of-pocket payments, whose share averaged 15.5 % in the EU in 2018. The share of out-of-pocket payments amounted to 44.6 % of the total in Cyprus, while these payments also accounted for around one third of total healthcare expenditure in Bulgaria, Latvia, Greece, Malta and Lithuania. France was the only EU Member State where household out-of-pocket payments accounted for less than one tenth (9.2 %) of healthcare expenditure.

(% of current healthcare expenditure)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf)

Voluntary health insurance schemes generally represented a small share of healthcare financing in the EU in 2018, averaging 3.9 %. Their relative share peaked at 14.0 % in Slovenia, while shares above one tenth were also recorded in Ireland and Cyprus. The shares in these three Member States were clearly greater than elsewhere, as the next highest share was 8.1 % (in Portugal). There were six EU Member States where voluntary health insurance schemes provided less than 1.0 % of the finance for healthcare expenditure in 2018, with the lowest share recorded in Czechia (0.1 %).

The final analysis concerning financing (see Figure 5), shows the same sources of financing as in Table 5, but presented as values per inhabitant (in PPS) rather than as a share of all healthcare expenditure. This analysis shows how much on average is spent per inhabitant from each of the different sources. The total for all sources (the overall height of each stacked bar) shows the overall expenditure per inhabitant. To put this in perspective, the EU Member States, the EFTA countries and Bosnia and Herzegovina have been ranked based on their overall level of current healthcare expenditure relative to GDP.

(PPS per inhabitant)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf)

Healthcare expenditure by function

Curative and rehabilitative care services accounted for more than half of current healthcare expenditure in all but three of the EU Member States

The functional patterns of healthcare expenditure presented in Figure 6 and Table 6 show that in 2017 curative and rehabilitative care services incurred more than 50.0 % of current healthcare expenditure in the vast majority of EU Member States, the exceptions being Latvia and Germany — where the shares were almost half (49.9 % and 49.8 % respectively — and Bulgaria (47.9 %). By contrast, at the upper end of the range, close to two thirds (66.7 %) of current healthcare expenditure in 2017 was incurred by curative and rehabilitative care services in Portugal, while Cyprus, Poland (2016 data) and Greece recorded shares that were above 60.0 %.

(% of current healthcare expenditure)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha_hc)

Medical goods accounted for just under one fifth of healthcare expenditure in 2017

Medical goods (non-specified by function) were the second largest function in the EU-27 in 2017, with an 18.8 % share of current healthcare expenditure (including 2016 data for Poland). There was a substantial variation between the EU Member States in terms of the share of expenditure used for these medical goods. The lowest shares — below 15.0 % — were recorded for Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark (where the lowest share was recorded, at 9.8 %). By contrast, the highest shares — where medical goods accounted for between 30.0 % and 35.0 % of current healthcare expenditure — were recorded for Hungary, Greece, Latvia and Slovakia, with this share peaking at 43.3 % in Bulgaria.

(% of current healthcare expenditure)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hc)

The proportion of healthcare expenditure incurred by long-term healthcare was 15.9 % in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland) in 2017: more information about this function is given in a special focus below.

The fourth largest function was ancillary services (such as laboratory testing or the transportation of patients), which accounted for 5.1 % of healthcare expenditure in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland) in 2017. The share of these services exceeded 10.0 % in Estonia and Cyprus. Expenditure related to health system governance and the administration of financing averaged 3.8 % in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland) in 2017 and ranged from 0.9 % in Finland to 5.7 % in France. Expenditure for preventive care averaged 2.7 % of current healthcare expenditure in 2017 in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland), ranging from 1.0 % in Slovakia to 4.2 % in Italy.

Long-term healthcare expenditure accounted for more than a quarter of current healthcare expenditure in the Netherlands and Sweden in 2017

As noted above, services related to long-term healthcare (see Figure 7) accounted for 15.9 % of current healthcare expenditure in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland) in 2017. This share was below 10.0 % in 14 of the EU Member States. Relatively low shares could be due to the main burden of long-term healthcare residing with family members, with no payment being made for providing these services. On the other hand, more than one fifth of healthcare expenditure was attributed to long-term healthcare in Ireland and Belgium, with this share reaching one quarter in Denmark and exceeding this level in Sweden and the Netherlands (both 26.5 %). Among the EFTA countries, a relatively high share (28.2 %) was recorded in Norway (higher than in any of the Member States). It should be noted that it can be difficult to separate the medical and social components of expenditure for long-term care, leading to an inevitable impact on cross-country comparisons.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hc)

Healthcare expenditure by provider

In expenditure terms, hospitals were the main provider of healthcare in most EU Member States

An analysis of current healthcare expenditure by provider is shown in Figure 8 and Table 7. It should be borne in mind that healthcare providers classified under the same group do not necessarily perform the same set of activities. For example, hospitals may offer day care, out-patient, ancillary or other types of service, in addition to in-patient services.

Hospitals accounted for the highest proportion (36.3 %) of healthcare expenditure in 2017 in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland). Among the EU Member States, the share of current healthcare expenditure related to hospitals ranged from 28.3 % of the total in Germany to 46.2 % in Croatia. Three Member States reported that hospitals did not have the highest share of healthcare expenditure: ambulatory health care providers accounted for a greater share of total healthcare expenditure in Germany; retailers and other providers of medical goods accounted for a higher share in Bulgaria and Slovakia.

(% of current healthcare expenditure)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hp)

The second largest healthcare provider (in expenditure terms) was generally that of ambulatory health care providers. Their share of current healthcare expenditure in 2017 averaged 25.6 % in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland) and ranged from 14.9 % in Bulgaria to 32.8 % in Belgium.

The share of current healthcare expenditure accounted for by retailers and other providers of medical goods averaged 17.6 % in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland) in 2017. However, their share varied greatly between the EU Member State, from 9.8 % in Denmark to 34.8 % in Slovakia and 42.9 % in Bulgaria.

Table 7 gives information on the relative size of the providers shown in Figure 8 as well as more detailed information on the shares of other providers. By far the largest of the other providers was residential long-term care facilities, which accounted for 10.2 % of current healthcare expenditure in the EU-27 (including 2016 data for Poland) in 2017. Among the EU Member States, this share varied even more than the share for retailers and other providers of medical goods: the highest share for residential long-term care facilities was 26.6 % in the Netherlands, while in Croatia and Bulgaria the share was below 1.0 % (no data available for Slovakia).

(% of current healthcare expenditure)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hp)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available value. |

Key concepts

Current healthcare expenditure quantifies the economic resources dedicated to health functions, excluding capital investment. Healthcare expenditure is primarily concerned with healthcare goods and services that are consumed by resident units, irrespective of where that consumption takes place (it may be in the rest of the world) or who is paying for it. As such, exports of healthcare goods and services (to non-resident units) are excluded, whereas imports of healthcare goods and services for final use are included.

Medical goods (non-specified by function) are split into i) pharmaceuticals and other medical non-durable goods and ii) therapeutic appliances and other medical durables. This category aims to include all consumption of medical goods where the function and mode of provision is not specified. It includes medical goods acquired by the beneficiary either as a result of prescription following a health system contact or as a result of self-prescription. It excludes medical goods consumed or delivered during a health care contact that are prescribed by a health professional.

Long-term healthcare consists of a range of medical and personal care services that are consumed with the primary goal of alleviating pain and suffering and reducing or managing the deterioration in health status in patients with a degree of long-term dependency. The aim of long-term social care is to provide services and support, by formal and informal care givers, to individuals who, for reasons of disability, illness or other dependency, need help to live as normal a life as possible. Social care covers a wide range of services, including professional advice and support, accommodation, various types of assistance in carrying out daily tasks, home visits, home help services, provision of meals, special equipment, house adaptation for disabled persons, as well as assessment and care management services. There may be a mixed economy of health and social care provision and this mix of services can make it difficult to separate expenditure between health and social components. For the purpose of this article, the analysis of long-term care (as shown in Figure 7) is composed solely of the health component.

System of health accounts

Eurostat, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) established a common framework for a joint healthcare data collection exercise. The data collected relates to healthcare expenditure following the methodology of the system of health accounts (SHA).

The SHA shares the goals of the system of national accounts (SNA): to constitute an integrated system of comprehensive, internally consistent, and internationally comparable accounts, which should as far as possible be compatible with other aggregated economic and social statistical systems. Health accounts provide a description of the financial flows related to the consumption of healthcare goods and services from an expenditure perspective. Health accounts are used in two main ways: internationally, where the emphasis is on a selection of comparable expenditure data; nationally, with more detailed analyses of healthcare spending and a greater emphasis on comparisons over time.

In 2011, and as a result of four years of extensive and wide-reaching consultation, Eurostat, the OECD and the WHO released an updated manual for the collection of health accounts, ‘A system of health accounts, 2011 — revised edition’. The core set of SHA tables addresses three basic questions: i) what kinds of healthcare goods and services are consumed; ii) which healthcare providers deliver them, and; iii) which financing schemes are used to deliver them?

Healthcare expenditure is recorded in relation to the international classification for health accounts (ICHA), defining:

- healthcare expenditure by financing schemes (ICHA-HF) — which classifies the types of financing arrangements through which people obtain health services; healthcare financing schemes include direct payments by households for services and goods and third-party financing arrangements;

- healthcare expenditure by function (ICHA-HC) — which details the split in healthcare expenditure following the purpose of healthcare activities — such as, curative care, rehabilitative care, long-term care, or preventive care;

- healthcare expenditure by provider (ICHA-HP) — which classifies units contributing to the provision of healthcare goods and services — such as hospitals, residential facilities, ambulatory health care services, ancillary services or retailers of medical goods.

Healthcare expenditure — methodology

Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/359 of 4 March 2015 implementing Regulation (EC) No 1338/2008 as regards statistics on healthcare expenditure and financing paves the way for healthcare expenditure data collection according to SHA 2011 methodology. The Regulation applies to data from reference year 2014 onwards and hence the information for the most recent years shown in this article presents a harmonised set of data based on this methodology.

Statistics on healthcare expenditure are documented in a background article which provides more information on the scope of the data, the legal framework, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions.

Context

Health systems across the globe are developing in response to a multitude of factors, including: new medical technology and improvements in knowledge; new health services and greater access to them; changes in health policies to address specific diseases and demographic developments; new organisational structures and more complex financing mechanisms. However, access to healthcare and greater patient choice is increasingly being considered against a background of financial sustainability. Many of the challenges facing governments across the EU were outlined in the European Commission’s White paper titled Together for health: a strategic approach for the EU 2008-2013 (COM(2007) 630 final), which built upon Council conclusions relating to Common values and principles in European Union Health Systems (2006/C 146/01).

In February 2013, the European Commission adopted the Communication Towards social investment for growth and cohesion (COM(2013) 83 final). Its main axes included: ensuring that social protection systems respond to people’s needs at critical moments throughout their lives; simplified and better targeted social policies, to provide adequate and sustainable social protection systems; and upgrading active inclusion strategies in the EU Member States.

In March 2014, the third multi-annual programme of EU action in the field of health for the period 2014-2020 was adopted (Regulation (EU) No 282/2014) under the title Health for Growth. This new programme emphasises the link between health and economic prosperity, as the health of individuals directly influences economic outcomes such as productivity, labour supply and human capital. A mid-term evaluation (COM(2017) 586 final) was published in October 2017. More information is provided in an introductory article for health statistics.

On the basis of Eurostat’s 2013 population projections (EUROPOP2013), long-run economic and budgetary projections aimed at assessing the impact of ageing population were published in 2015. This constituted the fifth release of such long-run projections since 2001. Taking account of underlying demographic and macro-economic assumptions and projections, age-related expenditures covering pensions, healthcare, long-term care, education and unemployment benefits were projected and analysed. These projections feed into a variety of policy debates in the EU. In particular, they are used in the context of the European semester so as to identify policy challenges, in the annual assessment of the sustainability of public finances carried out as part of the stability and growth pact. The latest release of the long-run economic and budgetary projections was in spring 2018, with the underlying demographic and macro-economic assumptions and projections having already been published at the end of 2017.

In May 2016, the European Commission adopted a strategic plan for promoting health and food safety for the period 2016-2020. In order to improve the quality and effectiveness of public expenditure and contribute to prosperity and social cohesion, the European Commission seeks to provide expertise on health systems and support actions that help prevent and reduce the impact of ill-health on individuals and economies, while encouraging and supporting innovation and the uptake of modern technologies for better care delivery and cost-effectiveness.

The Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety has constituted a list of 88 European core health indicators (ECHIs) for monitoring progress in relation to health policy and broader objectives. Among these, it recommends specifically following developments for:

Direct access to

Online publication

Methodology

General health statistics articles

- Health (hlth), see:

- Health care (hlth_care)

- Health care expenditure (SHA 2011) (hlth_sha11)

- A system of health accounts 2011 — revised edition

- Healthcare expenditure (SHA 2011) (ESMS metadata file — hlth_sha11_esms)

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — European core health indicators (ECHI)

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety — Health systems performance assessment

- European economy — The 2015 Ageing Report, Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2013-2060)

- European economy — The 2015 Ageing Report, Underlying assumptions and projection methodologies

- European economy — The 2018 Ageing Report, Economic and budgetary projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)

- European economy — The 2018 Ageing Report, Underlying assumptions and projection methodologies

- OECD — Health at a Glance

- OECD — Health policies and data

- WHO Global health observatory (GHO)

- World Health Organisation (WHO) — Health system governance