Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - education

- Data from June 2017. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables. Planned article update: June 2018.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles on the Europe 2020 strategy. It provides recent findings on education in the European Union (EU).

The Europe 2020 strategy is the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs for the current decade. It emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth as a way to strengthen the EU economy and prepare its structure for the challenges of the next decade.

Education is a key policy component of the Europe 2020 strategy. The EU’s education targets are interlinked with the other Europe 2020 goals as higher educational attainment improves employability, which in turn reduces poverty. The tertiary education target is furthermore interrelated with the research and development (R&D) and innovation target as investment in the R&D sector is likely to raise the demand for highly skilled workers.

Europe 2020 strategy target on education

The Europe 2020 strategy sets out a target of ‘reducing the share of early leavers of education and training to less than 10 % and increasing the share of the population aged 30 to 34 having completed tertiary or equivalent education to at least 40 %’ by 2020 [1].

The analysis in this article builds on the headline indicators chosen to monitor the Europe 2020 strategy's education targets: 'early leavers from education and training' and 'tertiary educational attainment'. The analysis starts with early school leaving and its impacts, followed by the typical educational pathway, starting with early childhood education, followed by the acquisition of basic skills (reading, maths and science) and foreign languages, leading to tertiary education and adult participation in learning. It then switches to the ‘outcome’ side, looking at educational attainment in general and its impacts on the labour market. The article finally investigates the input in the form of public expenditure on education.

Key messages

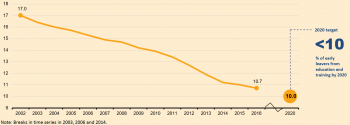

- Early leaving from education and training has been falling continuously in the EU since 2002, for both men and women. The fall from 17.0 % in 2002 to 10.7 % in 2016 represents steady progress towards the Europe 2020 target of 10 %.

- Fifteen countries have already reached their national targets for the rate of early leavers from education and training. Southern European countries made particularly strong progress between 2008 and 2016.

- Across the EU, rates of early leaving from education and training are generally higher for people who study away from the country in which they were born.

- Educational attainment strongly influences labour market participation. In 2016, about 58 % of 18 to 24 year old early leavers from education and training were either unemployed or inactive. Of the total population of 18 to 24 year olds, 15.2 % were neither in employment nor in any further education or training (NEET), putting them at risk of being excluded from the labour market.

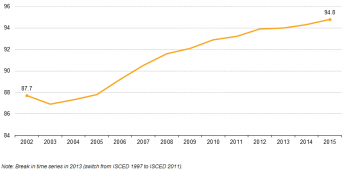

- Participation in early childhood education and care (ECEC) has grown more or less continuously in the EU since 2002. In 2015, 94.8 % of children between the age of four and the starting age of compulsory education participated in ECEC. This is very close to the ET 2020 benchmark of a participation rate of at least 95 %.

- In 2015, about one fifth of 15 year olds showed insufficient abilities in reading, maths and science. This is a step backward compared to 2012. As a result, the EU as a whole is seriously lagging behind in all three domains when it comes to progress towards the ET 2020 benchmark of less than 15 % low achievers.

- Between 2002 and 2016, the share of 30 to 34 year olds having completed tertiary education grew continuously from 23.6 % to 39.1 %. Growth was considerably faster for women, who in 2016 were already clearly above the Europe 2020 target at 43.9 %. In contrast, among 30 to 34 year old men the share was 34.4 % in 2016.

- The share of adults participating in learning does not seem to be increasing fast enough to meet the ET 2020 benchmark of raising participation to at least 15 % by 2020. Over the last four years, the share stagnated between 10.7 % (2013, 2015) and 10.8 % (2014, 2016).

- Educational attainment is the visible output of education systems. In general, younger people show higher educational levels than the older age group. And across all age groups, migrants born outside the EU (extra-EU migrants) have a much higher prevalence of low educational levels (ISCED 0–2) than people living in their country of birth or coming from another EU country (intra-EU migrants).

- Education and training plays an important role in improving employability. The employment rate of recent graduates (20 to 34 year olds having left education and training in the past one to three years) has dropped considerably due to the economic and financial crisis. It fell from 82.0 % in 2008 to 75.4 % in 2013. However, it has increased clearly since 2013, reaching 78.2 % in 2016.

- In 2014, public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP in the EU was highest for primary and lower secondary education (levels 1 and 2) and lowest — for early childhood and education.

Main statistical findings

Early school leaving is still decreasing

(% of the population aged 18–24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_40)

The EU defined upper secondary education as the minimum desirable educational attainment level for EU citizens. The skills and competences gained in upper secondary education are considered essential for successful labour market entry and as the foundation for adult learning. Therefore, the headline indicator ‘Early leavers from education and training’ measures the share of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and who were not involved in further education or training during the four weeks preceding the survey. Figure 1 shows that the share of early leavers has fallen continuously from 17.0 % in 2002 to 10.7 % in 2016. This trend mirrors reductions in almost all Member States for both men and women.

Overall, in the EU men tend to leave education and training earlier than women. This gap, which was 3 percentage points in 2016, has narrowed by 1.5 percentage points since 2004. However, for the first time since 2010, the gap has widened compared to the previous year. The rate for women is already below the headline target, with only 9.2 % leaving early in 2016.

At the country level, gender differences in 2016 were particularly strong in Spain, Latvia, Malta and Cyprus. Bulgaria and Romania were the only Member States where men were more likely to stay longer in education and training than women.

Substantial decreases in early leaving in southern European countries

(% of the population aged 18–24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_40)

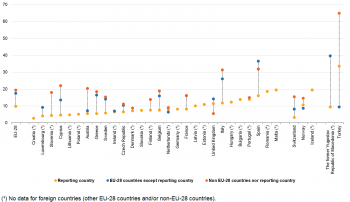

Reflecting different national circumstances, the overall EU target for early leavers from education and training has been transposed into national targets by all Member States except the United Kingdom. National targets range from 4 % for Croatia to 16 % for Italy (see Figure 2). In 2016, 15 countries had already achieved their targets: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, the Netherlands and Slovenia.

Rates of early leaving vary widely across Member States. In 2016, the lowest proportion of early leavers was observed in Luxembourg and some eastern European countries (Croatia, Lithuania, Poland and Slovenia), with rates of less than 6 %. The share was highest in Malta, Romania and Spain, with 18.5 % or more.

At the same time southern European countries experienced strong falls in early leaving between 2008 and 2016, especially Portugal (from 34.9 % to 14 %), Spain (from 31.7 % to 19 %) and Greece (from 14.4 % to 6.2 %). Overall, 17 Member States were already below the overall EU target of 10 % in 2016.

Of the candidate countries, Turkey had the highest share of early leavers, at more than three times the EU average.

(% of the population aged 18–24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_02)

Country of birth strongly influences the rate of early leaving across the EU (see Figure 3). People who study away from the country in which they were born are more likely to struggle to complete their education. Socioeconomic status underlies much of this difficulty, but issues associated specifically with immigration such as language barriers and settling into a new environment are also at play, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

Early school leaving leads to severe problems in the labour market

(% of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_14)

(% of population aged 18 to 24)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_20)

In general, low educational attainment — at most lower secondary education — influences other socioeconomic factors. The most important of these are employment, unemployment and the risk of poverty or social exclusion. Some of these relationships are also analysed in detail in other articles (see the articles on ‘Employment’ and ‘Poverty and social exclusion’).

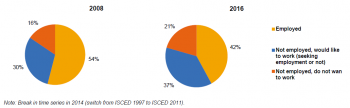

Early leavers from education and training and low-educated young people face particularly severe problems in the labour market. As shown in Figure 4, about 58 % of 18 to 24 year olds, with at most lower secondary education and who are not in further education or training, were either unemployed or inactive in 2016. The situation for early leavers has worsened over time: between 2008 and 2016, the share of 18 to 24 year old early leavers who were not employed but who wanted to work grew from 30 % to 37 %. For a further analysis on youth unemployment, see the article on ‘‘Employment’.

The indicator monitoring young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET) covers people aged 18 to 24 years. Low educational attainment is one of the key determinants of young people entering the NEET category. Other factors include having a disability or coming from a migrant background.

In 2016, 15.2 % of 18 to 24 year olds were neither in employment nor in education, exposing themselves to the risk of labour market exclusion and dependence on social security. This was an improvement since 2012 when the NEET rate peaked at 17.2 %, but was still higher than the 2008 low of 14.0 %.

Changes in the EU NEET rate have been mainly caused by changes in the unemployment rate of 18 to 24 year olds (see Figure 5). In comparison, the share of inactive youths has remained stable at, or just below, 8 %. The NEET rate was slightly higher for women (15.7 %) than for men (14.7 %). However, while women in the NEET category tended to be economically inactive, men were mostly unemployed.

Participation in early childhood education and care has reached the ET 2020 benchmark

(% of the age group between 4 years old and the starting age of compulsory education)

Source: Eurostat online data codes (tps00179) and (educ_uoe_enra10)

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) can bring wide-ranging social and economic benefits for individuals and for society as a whole. Quality ECEC provides an essential foundation for effective adult learning and future educational achievements. It also lays the foundations for later success in life in terms of well-being, employability and social integration. To realise these benefits, the EU aims to ensure that all young children can access and benefit from high-quality education and care (European Commission, 2014).

Participation in ECEC is crucial for preparing children for formal education, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. The aim is to reduce the incidence of early school leaving and thereby address one of the Europe 2020 headline targets on education. Investment in pre-primary education also offers higher medium- and long-term returns and is more likely to help children from low socioeconomic status than investment at later educational stages.

ET 2020 recognises ECEC’s potential for addressing social inclusion and economic challenges. It has set a benchmark to ensure that at least 95 % of children aged between four and the starting age of compulsory education participate in ECEC. As Figure 6 shows, participation has been rising more or less continuously in the EU since 2002 reaching 94.8 % in 2015 and therefore very close to the benchmark of 95 %. There are some variations on the country level. Half of the Member States had already exceeded the ET 2020 benchmark in 2015, implying almost universal pre-school attendance. France, Malta and the United Kingdom had already achieved a 100 % pre-school attendance, while in Belgium and Denmark participation rates were 98 % and above. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the lowest pre-school attendances were observed in Croatia (73.8 %) and Slovakia (78.4 %). When it comes to gender differences, very little variation in early childhood education can be seen across the EU.

Acquisition of skills such as reading, maths and science has taken a step backwards

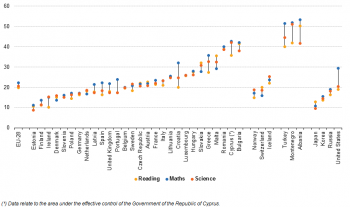

(Share of 15-year-old pupils who are below proficiency level 2 on the PISA scales for reading, maths and science)

Source: OECD/PISA online data code (tsdsc450)

All educational systems aim to equip people with a wide range of skills and competences. These encompass not only basic skills such as reading and mathematics, but also others like science and foreign languages.

Basic skills, whether reading simple texts or performing easy calculations, provide the foundations for learning, gaining specialised skills and personal development. These skills are also essential for people to fully participate in and contribute to society. The ET 2020 framework acknowledges the increasing importance of individual skills in the era of the knowledge-based economy. Therefore, one of the targets enshrined in the ET 2020 is to reduce the share of 15 year olds achieving low proficiency levels in reading, mathematics and science to less than 15 % by 2020.

In 2015, about one fifth of 15-year-old EU citizens showed insufficient abilities in reading, mathematics and science as measured by the OECD’s PISA study [2]. Test results were best for reading, with a 19.7 % share of low achievers, followed by science with 20.6 % and maths with 22.2 %. Figure 7 shows how the overall performance in reading, maths and science varied significantly across countries. It also indicates that performance is highly correlated across all three areas of basic skills. Member States that show certain levels of basic skills in one of the areas tend to show a similar value in the other areas.

The share of pupils failing to acquire competences in the key subjects surpassed 36 % in Bulgaria, Cyprus and Romania. However, only two countries (Estonia and Finland) reached the ET 2020 benchmark and had a share of low achievers with levels below 15 %. In general, there is no clear geographical pattern, with a number of eastern Member States performing better than the EU average while some northern and western Member States show lower rates.

Compared with international competitors, the EU’s overall share of low achievers in reading and science was similar to that of the United States while in maths US pupils performed significantly worse (29,4 %). However, it was higher than for Japan and Korea, where the shares of low-achieving pupils were below 13 % and 16 % respectively.

According to the European Commission’s PISA 2015 report, the EU as a whole is seriously lagging behind the 2020 target to have less than 15 % of low achievers in each of the three basic skill areas. The report also shows that progress has taken a step backwards, with the rate of low achievers increasing since the PISA 2012 results by 4 percentage points in science, 1.9 percentage points in reading and 0.1 percentage points in maths.

In general, gender differences are not as large as they used to be. The gender gap in the share of low achievers in maths (girls: 23.2 %, boys: 21.2 %) and science (girls: 20.4 %, boys: 20.7 %) continues to be small. The gap between boys and girls for reading (girls: 15.9 %, boys: 23.5 %) has narrowed significantly. In addition to basic skills in reading, maths and science, the ability of citizens to communicate in at least two languages besides their mother tongue has been identified as a key priority in the ET 2020 framework. The European Commission has proposed monitoring student proficiency in the first foreign language and the uptake of a second foreign language at lower secondary level. Member States must ensure the quantity and quality of foreign language education is scrutinised and that teaching and learning are geared towards practical, real-life application [3]. Foreign language skills should be taken into account in the effort to equip young people with the competences needed to meet labour market demands.

Schools teach foreign languages in all Member States, making language learning a central element in every child’s school experience across Europe. On average, 16.3 % of pupils across the EU in primary education (ISCED level 1) were not engaged in foreign language learning at this level in 2014 [4]. This number was higher in 2013, with 18.3 %. Looking at students in lower secondary education (ISCED level 2), the share learning no foreign language dropped to 1.4 % across the EU. On the other hand, students learning one foreign language reached nearly 40 % and students learning two or more foreign languages reached almost 59 % in 2015.

Increasing attainment at tertiary level

The share of tertiary graduates keeps growing

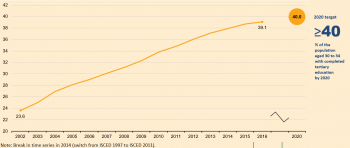

(% of the population aged 30–34 with completed tertiary education)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41)

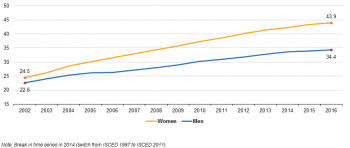

(% of the population aged 30–34 with completed tertiary education)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41)

The second Europe 2020 education target — raising the share of the population aged 30 to 34 that have completed tertiary or equivalent education to at least 40 % — is monitored with the headline indicator on tertiary educational attainment of the same age group [5].

Figure 8 shows a steady and considerable growth in the share of 30 to 34 year olds who have successfully completed a university degree or other tertiary-level education since 2002. The share of 39.1 % in 2016 implied a growth of 15.5 percentage points since 2002.

Tertiary education attainment rate is considerably higher for women

Figure 9 shows a significantly widening gender gap among graduates from tertiary education across the EU. While in 2002 the share of tertiary graduates was similar for both sexes, the share of female graduates has since grown at almost twice the rate. In 2016, women outnumbered men significantly in almost all Member States. In fact, the gender gap was more than 10 percentage points in 21 countries, with Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia showing the highest gaps of over 20 percentage points. Germany was the most ‘equal’ country with a gender gap of only 0.4 percentage points in favour of men.

All Member States made significant progress in raising tertiary educational attainment

(% of the population aged 30 to 34 with completed tertiary education)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41)

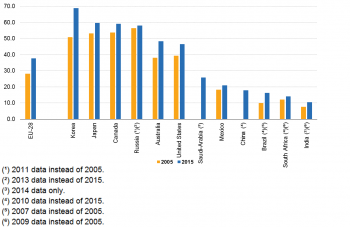

(%)

Source: OECD and Eurostat online data code (lfsa_pgaed)

The increase in tertiary educational attainment levels across the EU is mirrored across all Member States. This to some extent reflects countries’ investment in higher education to meet demand for a more skilled labour force. Another factor is the shift to shorter degree programmes following implementation of Bologna [6] process reforms in some countries.

National targets for tertiary education range from 26 % for Italy to 66 % for Luxembourg. Germany’s target is slightly different from the overall EU target because it includes post-secondary, non-tertiary attainment (ISCED level 4). For France, the target definition refers to the 17 to 33 year age group while for Finland the target excludes former tertiary vocational education and training (VET).

Figure 10 shows that in 2016, 13 countries had already achieved their national targets. Belgium, Hungary, Poland and Romania were close at less than two percentage points from their national targets while Luxembourg and Slovakia were the most distant, at 11.4 and 8.5 percentage points, respectively, below their targets.

In 2016, levels of tertiary educational attainment varied by a factor of about 2.3 across Europe. Northern and central Europe had the highest percentage of tertiary graduates, with 18 countries exceeding the overall EU target of 40 %. The lowest levels could be observed in Italy and Romania, which were both around 26 %.

At the same time, some eastern European countries experienced the strongest increases over the period 2008 to 2016. Changes were most pronounced in Latvia, Greece and the Czech Republic where the shares almost doubled.

Looking at non-EU Europe, the EFTA countries Norway, Switzerland and Iceland were at the level of the best performing Member States in 2016. However, the candidate countries FYR of Macedonia and Turkey showed tertiary educational attainment levels similar to southern and eastern Member States.

Across other major world economies [7], the tertiary attainment rates vary greatly, but all countries showed clear increases between 2005 and 2015 (see Figure 11). Korea experienced the biggest rise, with 18 percentage points.

Country-specific participation in adult learning varies greatly

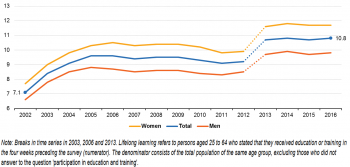

(% of population aged 25 to 64)

Source: Eurostat online data code (tsdsc440)

In addition to tertiary educational attainment, adult participation in learning is also crucial for providing Europe with a highly qualified labour force. Adult education and training covers the longest time span in the process of learning throughout a person’s life. After an initial phase of education and training, continuous, adult learning is crucial for improving and developing skills, adapting to technical developments, advancing careers or returning to the labour market (also see the article on ‘Employment’). In recognition of this, adult participation in learning plays a crucial role in the Europe 2020 flagship initiative 'An Agenda for new skills and jobs' and played an important role in the concluded initiative 'Youth on the move'. In addition, the European Council in 2011 adopted a resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning. The EU’s ET 2020 framework also includes a benchmark that aims to raise the share of adults participating in learning to at least 15 %. This benchmark refers to people aged 25 to 64 who stated they received education or training in the four weeks preceding the survey.

After growing between 2003 and 2005, the share of EU adults participating in learning fell slightly to 9.2 % in 2012 (see Figure 12). It increased to 10.7 % in the following year, but this rise was mainly influenced by a methodological change to the French Labour Force Survey [8]. In the last four years, the share stagnated between 10.7 % (2013, 2015) and 10.8 % (2014, 2016).

In most Member States, adult participation in learning stagnated or changed marginally between 2013 and 2016. Estonia showed the largest difference, where the rate increased by 3.1 percentage points. The United Kingdom experienced the largest fall of 2.2 percentage points. Overall, there are clear regional differences. The Scandinavian countries Sweden (29.6 %), Denmark (27.7 %) and Finland (26.4%) stand out with the highest rates, followed by western Member States such as France, the Netherlands (both 18.8 %) and Luxembourg (16.8 %). At the other end of the scale, Romania and Bulgaria had low shares of 1.2 % and 2.2 %. In general, adult learning seems to be a less common form of educational attainment in eastern and southern European countries.

Women are more likely to participate in adult learning than men. In 2016, the share of adult women engaged in learning was nearly 2 percentage points higher than that of men (11.7 % compared with 9.8 %). Women recorded higher participation rates in all Member States except for Germany and Croatia, where a slightly higher share of adult men were engaged in learning. Greece and Romania showed no perceivable difference in gender participation rates. Interestingly, the two countries with the highest shares in general had the largest gender differences: Sweden with 14.0 percentage points and Denmark with 9.9 percentage points.

Overall, the rates are higher for adults participating in learning in another Member State than the one they were born in (11.7 % in 2016). This may reflect participation in targeted learning activities such as language courses. It may also be linked to higher unemployment rates among migrants in some countries, resulting in a greater participation in labour market integration programmes (see the article on ‘Employment’).

There is a clear gradient of adult participation in learning and a person’s educational attainment. In 2016, adults with at most lower secondary education were less engaged in learning (4.2 %) than those with upper secondary (8.8 %) or tertiary education (18.6 %).

In relation to labour status, employed people in general show a slightly higher participation rate. Some 11.6 % of employed 25 to 64 year olds took part in adult learning in 2016. Among unemployed people, the rate was slightly lower than the total participation rate, at 9.6 %.

Educational levels of the population

People born outside the EU show higher prevalence of low education levels

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfs_9912)

Educational attainment is the visible output of education systems. Achievement levels can have major implications for many issues affecting a person’s life. This is reflected in adult participation inlearning as well as in other aspects presented in the articles on ‘Employment’ and ‘Poverty and social exclusion’.

Figure 13 shows the educational attainment level of different population groups. The age group 25 to 54 shows higher educational levels than the 55 to 74 age group, which reflects the growing demand for a more highly skilled workforce in most parts of Europe over the past few decades. A more skilled workforce is expected to emerge as older generations leave the workforce and are replaced by younger, more highly educated ones. If labour markets do not provide adequate jobs this may result in higher levels of over-qualification and youth unemployment. For workers aged 55 and older, lower educational attainment levels, especially among women, highlight the importance of adult learning to increase their employability and to help meet the Europe 2020 strategy’s employment target (see the article on ‘Employment’).

Across all age groups, migrants born outside the EU (extra-EU migrants) have a much higher prevalence of low educational levels (ISCED 0–2) than people living in their country of birth or coming from another EU country (intra-EU migrants). The reverse pattern can be observed for the medium education levels (ISCED 3–4). This rate is significantly lower for people from outside the EU, especially in the age group 25 to 54. Interestingly, the tertiary education rate for extra-EU migrants is similar to or higher than the rate for natives, while the tertiary education rate for intra-EU migrants is higher than for the native population.

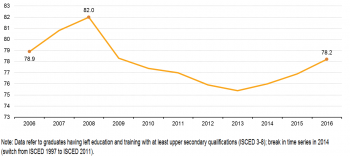

Employment rate of recent graduates

Increasing employment rate of recent graduates

(Share of graduates (20–34 year olds) having left education and training in the past 1–3 years who are employed and not in any further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_24)

The EU’s ET 2020 framework acknowledges the important role of education and training in raising employability. As a consequence, the EU aims to ensure that at least 82 % of recent EU graduates (20 to 34 year olds) should have found employment no more than three years after leaving education and training.

Figure 14 shows how severely the economic crisis has affected recent graduates. Between 2008 and 2013, employment rates among 20 to 34 year olds who had left education and training in the past one to three years, and were not in further education or training in the four weeks preceding the survey, fell by 6.6 percentage points. In comparison, the decline in the overall employment rate for 20 to 64 year olds was ‘only’ 1.9 percentage points over the same period. However, 2013 seems to mark a turnaround in this trend, with the share of employed recent graduates increasing in the three following years, reaching 78.2 % in 2016.

The data in Figure 14 refer to graduates who left education and training with at least upper-secondary qualifications (ISCED levels 3–8). Breaking the data down by educational attainment reveals the fall in the employment rate had been slightly stronger for the lower educated cohort (– 4.4 percentage points from 2008 to 2016) than for those with a tertiary education (– 4.1 percentage points from 2008 to 2016).

Investment in future generations: the case of public expenditure on education

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat online data code (educ_uoe_fine06)

Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP is often considered an indicator of a government’s commitment to developing skills and competences. Generally, the public sector funds education either by directly bearing the current and capital expenses of educational institutions or by supporting students and their families with scholarships and public loans as well as by transferring public subsidies for educational activities to private firms or non-profit organisations. Both types of transactions together are reported as total public expenditure on education.

Figure 15 shows the total public expenditure on education as a share of GDP in 2014. Data for all four education levels are available for 25 Member States. Nonetheless, all 26 Member States for which data are at least partly available have been included in the following analysis [9].

The highest share of public expenditure on education can be observed in Denmark (8.3 % of GPD), followed by Sweden (7.7 %), and Finland (7.2 %). The lowest proportions were reported by Romania (2.8 %), the Czech Republic (3.8 %) and Luxembourg (4.0 %).

Across the EU, public expenditure was highest for primary and lower secondary education (levels 1-2). As a share of GDP, this ratio ranged from 1.1 % in Romania to 3.3 % in Cyprus and Denmark.

By contrast, in nearly all countries, the smallest share of public expenditure on education went to early childhood education [10]. This ratio ranged from 0.1 % in Ireland to 1.8 % in Sweden. In general, in eight of the 25 Member States, public expenditure on this level of education was less than 0.5 % of GDP.

For the two remaining categories (upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education (levels 3-4) and tertiary education (levels 5-8), the differences were not as high as for the two lower categories. For upper secondary education (including also post-secondary non-tertiary levels), the range of public expenditure was equivalent to 0.7 % of GDP in Lithuania and Romania to 1.9 % of GDP in Belgium.

The proportion of financial resources devoted to the tertiary level varied between the 26 Member States for which data are available, ranging from 0.5 % in Luxembourg to 2.3 % in Denmark.

Outlook towards 2020

Knowledge of current student cohorts and demographic projections allow educational trends to be estimated up to 2020. This can help identify priority issues that may need particular political attention on the path to meeting the Europe 2020 targets.

Based on the most recent data for early school leaving and tertiary education, the European Commission has published projections of the likelihood that Europe 2020’s education targets will be met by 2020:

- The EU average early school leaving rate in 2010 was 13.9 % and would need to be below 10 % by 2020, ten years later. It follows from a basic calculation that the minimum annual progress required for the EU as a whole during this period is – 3.3 %, whereas the observed annual progress for the EU between 2010 and 2016 has been – 3.8 %. This means that overall the EU is on track to meeting the headline target if current progress is sustained.

- The EU average tertiary attainment rate in 2010 was 33.8 % and it would need to reach 40 % ten years later. The resulting minimum annual progress required for the EU as a whole is 1.8 %, while the observed annual change between 2010 and 2016 has been considerably higher (2.5 %). This means the EU is well on track to reach its 40 % target by 2020 if recent progress can be sustained.

Of the 12.0 million 30 to 34 year olds with a tertiary education qualification, 7.2 million are women. This highlights a significant gender difference in relation to obtaining a high-level education. Moreover, this difference has been increasing, up by 0.3 percentage points from 2011. In fact, women, taken as a separate group, achieved the 40 % benchmark in 2012, eight years ahead of the 2020 target date.

The flagship initiative ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs’ addresses the challenge of early leaving from education and training. In 2011, the European Council published recommendations on policies to reduce early leaving from education and training, giving guidance to Member States on the implementation of strategies and measures tackling this problem. Vocational Education and Training (VET) systems are seen as important for improving the employability of young people and reducing early leaving from education and training, by offering an interesting alternative to general education.

Additionally, the Europe 2020 strategy puts particular effort into making sure that higher education courses develop the skills relevant to the world of work, both for meeting future labour demand and for ensuring the long-term attractiveness of higher education. Moreover, the European Council’s Resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning addresses the challenge of raising participation rates of adults in learning activities.

Data sources and availability

Indicators presented in the article:

- Early leavers from education and training’ (t2020_40)

- Breakdown by broad group of country of birth (edat_lfse_02)

- Breakdown by labour status (edat_lfse_14)

- Young people neither in employment nor in education by sex and age (NEET rates) (edat_lfse_20)

- Participation in early childhood education (tps00179)

- Pupils between 4 years and the starting age of compulsory education - as % of the corresponding age group (educ_uoe_enra10)

- Low achievers in reading, maths and science: OECD/PISA (tsdsc450)

- Tertiary educational attainment (t2020_41)

- Breakdown by sex (t2020_41)

- Breakdown by country and other main economies (lfsa_pgaed)

- Adult participation in learning (tsdsc440)

- Population by educational attainment level, age and country of birth (edat_lfse_9912)

- Employment rate of recent graduates (edat_lfse_24)

- Total public expenditure on education by education level and programme orientation (educ_uoe_fine06)

Context

Education and training lie at the heart of the Europe 2020 strategy and are seen as key drivers for growth and jobs. The recent economic crisis along with an ageing population, through their impact on economies, labour markets and society, are two important challenges that are changing the context in which education systems operate [11]. At the same time, education and training help boost productivity, innovation and competitiveness.

Nowadays upper secondary education is considered the minimum desirable educational attainment level for EU citizens. Young people who leave education and training prematurely lack crucial skills and run the risk of facing serious, persistent problems in the labour market and experiencing poverty and social exclusion. Early leavers from education and training who do enter the labour market are more likely to be in precarious, low-paid jobs and to draw on welfare and other social programmes. They are also less likely to be ‘active citizens’ or engage in adult learning.

In addition, tertiary education, with its links to research and innovation, provides highly skilled human capital (see the article on ‘R&D and innovation’). A lack of these skills presents a severe obstacle to economic growth and employment in an era of rapid technological progress, intense global competition and labour market demand for ever-increasing levels of skill. The Europe 2020 strategy, through its ‘smart growth’ priority, aims to tackle early school leaving and to raise tertiary education levels.

The analysis in this article builds on the headline indicators chosen to monitor the strategy’s education targets: ‘Early leavers from education and training’ and ‘Tertiary educational attainment’. Contextual indicators are used to provide a broader picture and insight into drivers behind changes in the headline indicators. Some are also used to monitor progress towards additional benchmarks set under the EU’s Strategic Framework for Education and Training 2020 (ET 2020). These indicators include early childhood education, basic reading, maths and science skills and adult participation in learning. The benchmarks are listed in the section 'Data sources and availability'.

ET 2020 — the EU’s Strategic Framework for Education and Training 2020

The two Europe 2020 education targets also feature as EU benchmarks under the Strategic Framework for Education and Training 2020 (ET 2020). ET 2020 aims to foster European co-operation in education and training, providing common strategic objectives for the EU and its Member States up to 2020. ET 2020 covers the areas of adult participation in learning and mobility; quality and efficiency of education and training; equity, social cohesion and active citizenship; and creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship at all levels of education and training. To support the achievement of these objectives ET 2020 sets EU-wide benchmarks. In addition to the two Europe 2020 targets for education, there are another five benchmarks:

- At least 95 % of children between the age of four years and the age for starting compulsory primary education should participate in early childhood education.

- The share of low-achieving 15 year olds in reading, mathematics and science should be less than 15 %.

- The share of graduates (20 to 34 year olds) having left education and training in the past one to three years who are employed and not in any further education and training should be at least 82 %.

- An average of at least 15 % of adults should participate in learning.

- An EU average of at least 20 % of higher education graduates and of at least 6 % of 18 to 34 year olds with an initial vocational qualification should have spent some time studying or training abroad.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Towards robust quality management for European Statistics - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council COM(2011) 211 final

Other information

- Regulation (EC) No 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

External links

Notes

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels, 2014.

- ↑ PISA is an international study that was launched by the OECD in 1997. It aims to evaluate education systems worldwide every three years by assessing 15-year-olds’ competencies in the key subjects: reading, mathematics and science.

- ↑ The Member States play an important role in the development of national assessments of language learning. See in particular the May 2014 Council Conclusions on Multilingualism and the development of language competence.

- ↑ Data source: Eurostat (online data code: (educ_uoe_lang02))

- ↑ Educational attainment is defined according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Tertiary educational attainment refers to ISCED 2011 level 5–8 (for data as from 2014) and to ISCED 1997 level 5–6 (for data up to 2013).

- ↑ The Bologna process put in motion a series of reforms to make European higher education more compatible, comparable, competitive and attractive for students. Its main objectives were: the introduction of a three-cycle degree system (bachelor, master and doctorate); quality assurance; and recognition of qualifications and periods of study (source: Education and training statistics introduced).

- ↑ The data in figure 11 refers to the age group 25–34, because the OECD database does not include the age group 30–34 that is used for the Europe 2020 target.

- ↑ INSEE, the French Statistical Office, has carried out an extensive revision of the questionnaire of the Labour Force Survey. The new questionnaire was used from 1 January 2013 onwards. It impacts significantly the level of various French LFS-indicators. Detailed information on these methodological changes and their impact is available in INSEE’s website.

- ↑ There are no data available for Croatia and Greece.

- ↑ The analysis takes in consideration all ISCED0 levels (i.e. early childhood education development - ISCED01 and pre-primary education - ISCED02). Data on early childhood education development are not obligatory by the EU Regulation, therefore not provided by all countries.

- ↑ For further information on the impact of demographic ageing on the labour force, see the article on ‘Employment’.