Data extracted in February 2025

No planned article update.

Highlights

Self-employed people were more likely to continue working while receiving an old-age pension; 56.4% of self-employed people remained in the labour market, compared to just 24.4% of employees.

People with higher education levels and those in certain occupations (such as managers, skilled agricultural workers and professionals) were more likely to continue working after receiving their first old-age pension.

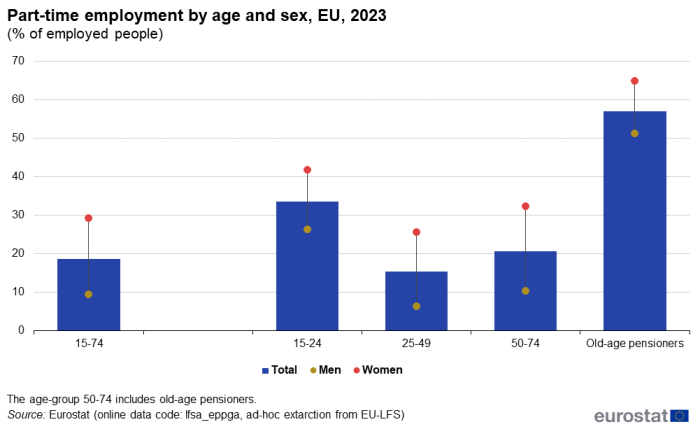

In 2023, more than half (57.0%) of old-age pensioners in the EU worked part-time, a higher rate than among the broader population.

This article examines the working life characteristics of individuals approaching retirement age. It focuses on educational attainment, occupation, professional status, part-time work and usual working hours. For a general overview of pension systems and the transition to retirement, see the Statistics Explained article Pensions and labour market participation - main characteristics.

Comparing pensioners who stopped and continued working

In 2023, in the EU:

- 64.7% of people stopped working within 6 months of receiving their first old-age pension

- 22.4% had not been working before receiving their pension

- 13.0% continued to work after 6 months from receiving the first old-age pension (full data for the first 3 bullet points can be found in the dataset lfso_23pens06)

- Additionally, 4.5% of old-age pensioners who had either stopped working or were not working, re-entered the labour market (full data can be found in the dataset lfso_23pens09).

Of the pensioners with known working status who were employed on or after receiving their first old-age pension, 78.5% stopped working permanently, while 21.5% either continued working or started working again. The share of people who continued working after receiving their first old-age pension varied significantly across countries, ranging from less than 2% in Romania to over 50% in Estonia. Re-entry into the labour market was more common in Sweden (15.6%), Estonia (12.4%) and Finland (12.2%) where the share of pensioners who continued working was also relatively high. In contrast, less than 1% of pensioners in Spain and Cyprus re-entered the labour market.

Educational level

The decision to stop or continue working after receiving an old-age pension is influenced by the level of educational attainment. As shown in Figure 1, employed people with higher education levels are more likely to continue working (30.8%) than those with lower education levels (14.5%). A high level of education means tertiary education, spanning short-cycle tertiary, bachelor's, master's or doctoral levels (or equivalents; ISCED levels 5-8), while a low level means (at most) primary or lower secondary education (ISCED levels 0-2).

Field of education

Among those with medium and high levels of education, the field of education was also relevant to employment decisions after receiving the old-age pension, as shown in Figure 2. Almost one third (32.3%) of people who had studied health and welfare chose to stay working for longer, a higher proportion than those from other fields of education. In contrast, the lowest share of people who continued working after receiving their old-age pension was found among those with generic programmes and qualifications (18.8%).

Professional status and occupation

In the analysis that follows, for pensioners who were still employed in 2023, their professional status and occupation in that job were considered. For those not employed in 2023, their previous professional status and occupation were used, provided they had stopped working less than 7 years prior. Information on current or previous working situations was available for approximately half of the pensioners who stopped, continued working or re-entered the labour market.

The comparability of the data on professional status and occupation is limited. For pensioners who stopped working, the data reflect their situation when they received their first pension, whereas for those who continued working or re-entered the labour market, the data pertain to their current or last job, which may have differed from the situation when they received their first old-age pension receipt.

The analysis reveals that employees were more likely to leave the labour market than self-employed persons or contributing family workers. As shown in Figure 3, over half of self-employed persons (56.4%) kept working, compared with just a quarter of employees (24.4%). This suggests that self-employment may be a factor that encourages older people to continue working beyond retirement age.

(% of old-age pensioners)

Source: Eurostat (lfso_23pens11)

An analysis of occupational groups reveals that people in 3 major groups were more likely to continue working after receiving their first old-age pension: managers, skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers and professionals (Figure 4). In contrast, clerical support workers had the lowest share of individuals who continued working, making them the least likely to remain in the labour market after receiving their old-age pension.

(% of old-age pensioners)

Source: Eurostat (lfso_23pens12)

Working conditions of employed old-age pensioners

Part-time working

In 2023, 10.2% of old-age pensioners aged 50-74 were employed (see Pensions and labour market participation - main characteristics). Among this group, a significant proportion worked part-time, with more than half (57.0%) of employed old-age pensioners in the EU engaged in part-time employment (Figure 5). In the broader population, just 20% of employed people aged 15-74 and 50-74 worked part-time.

The preference for part-time employment was even more pronounced among female old-age pensioners, with 64.9% working part-time compared to 51.2% of male pensioners. This pattern is consistent with the overall trend observed across all age groups, where women are more likely to work part-time than men.

(% of employed people)

Source: Eurostat ( (lfsa_eppga), ad-hoc extraction from EU-LFS)

Figure 6 illustrates the share of part-time employment among people aged 50-74, distinguishing between old-age pensioners and those who had not yet reached pension age. Part-time employment was more common among old-age pensioners in all countries. However, this difference varies significantly across countries. Croatia had the highest share of part-time employed old-age pensioners (89.4%) and the largest disparity with non-pensioners (3.4%), resulting in a substantial gap of 86 percentage points.

In contrast, Bulgaria reported the lowest share of part-time employment among old-age pensioners (9.2%) and non-pensioners (1.2%). Interestingly, the Netherlands, which has the highest overall share of part-time employment, displayed the smallest relative difference between old-age pensioners (57.8%) and non-pensioners (39.4%).

The reasons for people working part-time vary. In 2023, 18.5% of part-time employed people aged 15-74 worked part-time because they were unable to find a full-time job, a phenomenon referred to as involuntary part-time employment. As shown in Figure 7, involuntary part-time employment depended on age, peaking among those aged 25-49 years and declining for both younger and older age groups.

Old-age pensioners had a significantly lower rate of involuntary part-time employment, at just 4.3%. This suggests that, in contrast to other age groups, old-age pensioners who work part-time do so mainly by choice, preferring a less intense working pattern.

(% of total part-time employment)

Source: Eurostat ( (lfsa_eppgai), ad-hoc extraction from EU-LFS)

Working hours

The high prevalence of part-time employment among old-age pensioners is reflected in their average usual working hours, which are lower than the overall average (see Actual and usual hours of work). A clear geographical pattern emerged, as illustrated in Map 1. In northern and central Europe, old-age pensioners worked between 20 and 26 hours a week on average. Those in eastern and southern Europe worked significantly longer hours, with Bulgaria and Greece recording the highest averages at 38.8 and 38.5 hours a week, respectively.

Temporary employment

As illustrated in Figure 8, a clear age pattern emerges with regard to temporary employment. In 2023, nearly half (48.1%) of employed people aged 15-24 in the EU held temporary contracts. But the share of temporary contracts decreased significantly with age, with 11.9% of employed people aged 25-49 and just 6.8% of those aged 50-74 holding temporary contracts.

Employed old-age pensioners had a substantially higher share of temporary contracts, with a rate three times higher (21.8%) than that of the overall 50-74 age group. Furthermore, a slight difference by sex is observed, with temporary contracts slightly more common among women than men across all age groups, although the gender gap remains relatively small, ranging from 1.0 to 2.4 percentage points.

(% of employees)

Source: Eurostat ( (lfsa_etgaed), ad-hoc extraction from EU-LFS)

Among employees aged 15-74 with temporary contracts, the primary reason for holding such a contract is that a permanent contract was not available. Approximately half of this group reported that they were unable to find a permanent job or that the job was only available on a temporary basis (Figure 9). A relatively small proportion (10.4%) of employees in this age group said they wanted a temporary contract. The share of voluntary temporary employment among employees aged 50-74 was higher, at 14.3%.

However, the situation is reversed among employed old-age pensioners, 40.9% of whom said they preferred temporary work. Conversely, only about one quarter of old-age pensioners cited the unavailability of a permanent job as the reason for their temporary employment. This suggests that, unlike younger employees, many old-age pensioners are opting for temporary work arrangements by choice, rather than due to a lack of alternative opportunities.

(% of temporary employees)

Source: Eurostat ( (lfsa_etgar), ad-hoc extraction from EU-LFS)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources and methods

The article is part of a series on findings from the EU Labour force survey (EU-LFS) and its module on pensions and labour market participation, which was carried out in 2023. The module provides data for the European Union (EU) and all its member countries, plus 3 EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland).

The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour market characteristics of people. EU-LFS covers the resident population, defined as all people usually residing in private households.

Since 1999, an inherent part of EU-LFS has been the modules. These were called 'ad hoc modules' until 2020. From 2021 onwards, they are called either '8-yearly modules' when the variables have an 8-yearly periodicity or 'modules on an ad hoc subject' for variables not included in the 8-yearly datasets. In 2023, EU-LFS included an 8-yearly module on pensions and labour market participation. The planned date for the next module on pensions and labour market participation is 2031.

For further information on the EU-LFS modules, please refer to the article EU labour force survey - modules on this subject.

Coverage: The 2023 EU-LFS module on pension and labour market participation covers all European Union countries and the EFTA countries Norway and Switzerland. For Cyprus, the survey covers only the areas of Cyprus controlled by the Government of the Republic of Cyprus. Only persons aged 50-74 are covered by the module.

European aggregates: EU and EU-27 refer to the sum of the 27 EU Member States.

Calculation of percentages: All of the figures in this article present percentages of a total. The calculation of percentages used in this article is based on a total excluding the number of people classified in the non-response category. Accordingly, all exhaustive breakdowns presented in the figures should amount to 100 % (allowing for rounding errors).

Cluster analysis: The analysis was conducted by means of K-means algorithm.

Definitions

- Old age pension - in this article old-age pension covers statutory pension, occupational pension and/or personal pension.

- Disability pension - periodic payments intended to maintain or support the income of someone below the legal/standard retirement age as established in the reference scheme who suffers from a disability which impairs their ability to work or earn beyond a minimum level laid down by legislation.

- Statutory pension - covers the provision of social protection against the risks linked to old age: loss of income, inadequate income, lack of independence in carrying out daily tasks and, reduced participation in social life.

- Occupational pension - private supplementary plans linked to an employment relationship or professional activity. Contributions are made by employers or employees, or both, based on earnings, or by the self-employed. These plans may be mandated by national legislation but more commonly are included either in employment contracts or in sector-based or profession-based collective agreements, negotiated by social partners. Pension liabilities may be assumed directly by the sponsoring company (as book reserves), or contributions may be invested in private funds or insurance contracts. Funding may be based on defined benefit or defined contribution principles (the latter are increasingly common). Particularly in countries where public pensions only provide a minimal level of support, occupational pensions allow many employees to even out consumption over a lifetime and to enjoy, in retirement, a standard of living close to what they had during their working life.

- Personal pension - private voluntary plans in which contributions are invested in an individual account managed by a pension fund or financial institution. These are usually defined contribution plans, where the level of assets determines the level of complementary pension benefits provided. To encourage this specific kind of savings, countries often provide tax incentives or additional contributions. A personal pension plan may:

- be based on a contract between an individual saver and an entity on a voluntary basis;

- have an explicit retirement objective;

- provide for capital accumulation until retirement with only limited possibilities for early withdrawal before retirement;

- provide an income on retirement.

Context

With populations ageing across the EU, pensions, healthcare and long-term care systems are at risk of becoming financially unsustainable, as a shrinking labour force may no longer be able to provide for a growing number of older people. Active ageing is the European Commission’s policy directed towards ‘helping people stay in charge of their own lives for as long as possible as they age and, where possible, to contribute to the economy and society’. Policymakers hope to address these challenges by turning them into opportunities, with a focus on extending working lives and providing older people with access to adequate social protection and, where necessary, supplementary pensions.

The European Pillar of Social Rights stresses, in its Principle 15:

- the right of workers and the self-employed to a pension commensurate with contributions and ensuring an adequate income

- the right to equal opportunities to acquire pension rights for both women and men

- the right to resources that ensure living in dignity in old age.

Explore further

Other articles

Database

Thematic section

Publications

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2021, 2024 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2020, 2022 edition

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- European Union Labour force survey - selection of articles (Statistics Explained)

Methodology

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- Labour force survey (LFS) – Main concepts

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2021, 2024 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2020, 2022 edition

- Statistical working papers / Manuals and guidelines

ESMS metadata files and EU-LFS methodology

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (ESMS metadata file — lfso_esms)