Archive:Construction statistics - NACE Rev. 2

- Data from June 2011, most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database

This article presents an overview of statistics for European Union (EU) construction, covering NACE Rev. 2 Section F. In NACE a distinction is made between two general types of construction activity and a collection of specialised activities:

- construction of buildings (Division 41);

- civil engineering (Division 42);

- specialist activities (Division 43) such as:

- site preparation (including demolition and earth moving),

- installation activities (such as installation of electrical wiring and fittings, heating systems, plumbing, elevators and insulation),

- completion and finishing activities (such as plastering, joinery, flooring, glazing or painting),

- other specialist activities such as roofing, pile driving, scaffolding.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

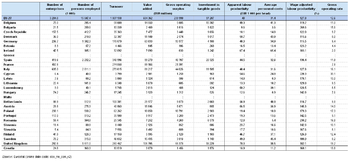

(% share of value added and employment within construction (NACE Section F))

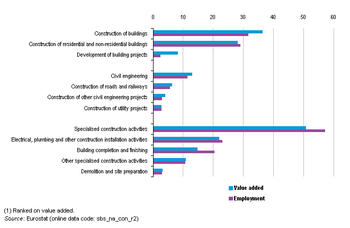

Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

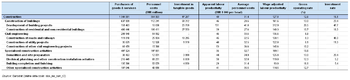

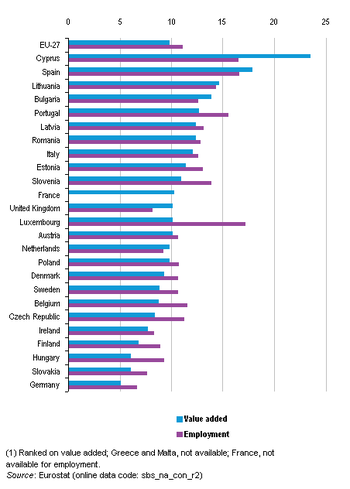

(% share of value added and employment in the non-financial business economy total)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

(cumulative share of the five principal Member States as a % of the EU-27 total)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_na_con_r2)

(top 20 NUTS 2 regions, based on % share of non-financial business economy workforce)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_r_nuts06_r2)

(% share of non-financial business economy workforce by NUTS 2 region)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_r_nuts06_r2)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_r_nuts06_r2)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_con_r2)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_con_r2)

(% share of sectoral value added)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_con_r2)

(% share of sectoral employment)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_con_r2)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_con_r2)

Some technical activities related to the construction sector, although not formally part of it, such as architectural services, are classified as business services (see professional, scientific and technical activity statistics). Some providers of real estate services are closely related to construction and these are covered in the article on real estate activity statistics.

The financial and economic crisis had a major impact on the construction sector in nearly all EU Member States. Output and employment fell sharply in many of the Member States, particularly in Spain and the Baltic Member States. Between February 2008 and December 2010 the EU-27’s production index for construction fell by one fifth (-20.1 %) underlining both the length and severity of the downturn in this activity. In the first three months of 2011 the trend cycle of the EU-27’s production index for construction recorded successive positive rates of change, the first sustained growth since early 2008. The massive change in market conditions during 2008 and following years should be borne in mind when considering the data presented in this article which are mainly related to the overall annual situation in 2008.

Main statistical findings

Structural profile

The EU-27’s construction sector (Section F) was made up of 3.3 million enterprises in 2008, employing 15.0 million persons and generating EUR 604 400 million of value added. As such the sector accounted for 15.6 % of all enterprises in the non-financial business economy (Sections B to J and L to N and Division 95), employed 11.0 % of its workforce, and generated 9.8 % of the value added. The construction sector can be characterised as having enterprises that are on average smaller than the non-financial business economy average both in terms of employment and value added, and that labour productivity is below average.

The level of tangible investment made by the construction sector in 2008 reached EUR 97 300 million in the EU-27, equivalent to 9.7 % of all tangible investment made in the non-financial business economy, roughly in line with the sector’s contribution to value added.

The share of personnel costs in operating expenditure (personnel costs plus purchases of goods and services) was 21.3 % in the EU-27’s construction sector in 2008, above the non-financial business economy average of 16.1 %, underlining the importance of labour input in the construction activity as a whole: at a more detailed level a number of the construction activities are also very capital intensive, such as the construction of roads and railways (Group 42.1) or the development of building projects (Group 41.1). Apparent labour productivity in the EU-27's construction sector in 2008 was EUR 40 thousand per person employed and average personnel costs were EUR 31.4 thousand per employee. While the apparent labour productivity was below the average for the non-financial business economy the average personnel costs were higher. The relatively low level of the apparent labour productivity is all the more notable given the small proportion of part-time employment within this sector: part-time employment has the effect of making this ratio lower as this productivity measure is calculated on a per head basis. The wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio combines the two previous ratios and is less affected by issues of part-time employment and so facilitates analysis between activities. This ratio is also adjusted for the relative importance of unpaid working proprietors and family workers which is higher in the construction sector (23 %) than in the non-financial business economy as a whole (14 %). The wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio shows that value added per person employed in the EU-27's construction sector in 2008 was equivalent to 127.8 % of the average personnel costs per employee, well below the average for the non-financial business economy which was 146.3 %.

Unlike the productivity indicators, the gross operating rate (the relation between the gross operating surplus and turnover) in the construction sector in the EU-27 in 2008 was above the average for the non-financial business economy, reaching 12.6 % for construction compared with 10.2 % for the non-financial business economy. This is partly an effect of the relatively high share of self-employment in construction, as working owners and other unpaid persons employed contribute to the value added but are recompensed through a share of profits not in the form of personnel costs, so boosting the gross operating surplus.

Sectoral analysis

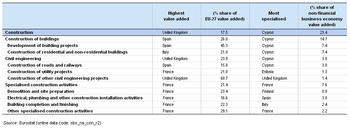

There were around 2.2 million enterprises in the EU-27’s specialised construction activities subsector (Division 43) in 2008, just over two thirds of all construction enterprises. Most of the remainder, around 940 thousand enterprises, were classified to the construction of buildings subsector (Division 41) and the rest (99 thousand or 3.0 % of the construction total) were in the civil engineering subsector (Division 42). On average, civil engineering enterprises were relatively large: the civil engineering share of construction employment was 11.4 % and its value added share reached 13.0 %. The construction of buildings subsector also accounted for a larger proportion of construction employment (31.5 %) and value added (36.2 %) than its share of the number of enterprises. Although the specialised construction activities subsector’s share of construction was much smaller in employment and value added terms than based simply on the number of enterprises it was nevertheless the largest subsector according to both of these measures and in fact contributed more than half of the construction total. Within this subsector the largest activities were construction installation activities (Group 43.2) and building completion and finishing activities (Group 43.3) – see Figure 1.

Apparent labour productivity ranged from EUR 36 thousand per person employed in the specialised construction activities subsector to EUR 46 thousand per person employed for both the building and civil engineering subsectors, the latter being above the non-financial business economy average. Average personnel costs ranged from EUR 28.6 thousand for the construction of buildings which was below the non-financial business economy average, to EUR 33.6 thousand for civil engineering. As already noted, the wage adjusted labour productivity ratio for the construction sector was relatively low, and this was in large part due to the particularly low ratio (109.1 %) in the specialised construction activities subsector, although the ratio in civil engineering (136.6 %) was also below the non-financial business economy average. The construction of buildings recorded by far the highest wage adjusted labour productivity ratio among the three construction subsectors, mainly due to the activity of the development of building projects where it reached 312.9 %, whereas in the larger activity of the construction of residential and non-residential buildings (Group 41.2) the ratio was 140.3 %, just below the non-financial business economy average and broadly in line with the ratio for civil engineering.

The construction of buildings recorded a relatively high investment rate (23.4 %), but it should be noted that this was elevated by the 47.7 % rate recorded for the development of building projects, underlying the capital intensive nature of this particular construction activity which involves bringing together financial, technical and physical means to bring building projects to fruition for later sale. The remaining activity within the subsector, the construction of residential and non-residential building, recorded a more modest investment rate of 16.3 % which was the same as the non-financial business economy average. Within civil engineering the construction of roads and railways also recorded a particularly high investment rate (48.3 %) reflecting the extensive use of machinery on the large scale projects typical in this activity; a similar situation could be seen for demolition and site preparation (Group 43.1) where the investment rate reached 20.4 %.

Country analysis

In value added terms, the United Kingdom had the largest construction sector in the EU-27 with a 17.5 % share of the EU-27 total in 2008, in line with its overall share of the EU-27 value added in the non-financial business economy. The Spanish construction sector had the second highest contribution to EU-27 value added, 16.4 %, which was 1.8 times as high as its average share for the non-financial business economy as a whole; France and Italy also recorded shares of the EU-27 value added for the construction sector that were higher than their equivalent shares for the non-financial business economy. In contrast Germany contributed 10.6 % of EU-27 value added in the construction sector, approximately half its average (20.3 %) for the non-financial business economy. In value added terms Spain had the largest subsector for the construction of buildings, the United Kingdom had the largest civil engineering subsector, and France the largest subsector for specialised construction activities.

The construction sector contributed 23.4 % to Cypriot value added in the non-financial business economy and 17.8 % to Spanish value added, making these the most specialised Member States in value added terms by far: the next highest share was 14.6 % in Lithuania. The least specialised in value added terms was Germany as the construction sector contributed just 5.1 % of non-financial business economy value added, around half the average for the EU-27 as a whole. Slovakia, Hungary, Finland and Ireland were the next least specialised in the construction sector, as this sector accounted for less than 8.0 % of the value added generated in their respective non-financial business economies. In employment terms a slightly different situation can be observed. Cyprus and Spain remained near the top of the ranking with construction providing 16.5 % of the non-financial business economy workforce in both of these Member States, but Luxembourg reported a higher share, 17.2 %.

Productivity in the Member States can be compared using the wage adjusted labour productivity ratio which shows the relative level of value added per person employed compared with average personnel costs, in other words the average value of output per person compared with the average cost of personnel input. Bulgaria and Romania had by far the lowest average personnel costs in the construction sector and this was reflected in their high wage-adjusted labour productivity ratios (269.6 % and 238.2 % respectively). Cyprus recorded relatively high apparent labour productivity combined with personnel costs per employee below the EU-27 average resulting in the third highest wage adjusted labour productivity ratio (220.3 %), ahead of the United Kingdom (182.1 %) which had recorded the highest apparent labour productivity. The lowest wage adjusted labour productivity ratios (below 110 %) were recorded in Ireland and Sweden reflecting their high average personnel costs, particularly in Ireland where the personnel costs per employee were more than double the EU-27 average.

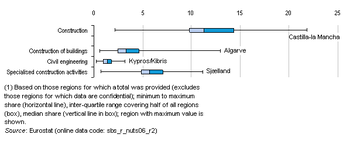

Regional analysis

The contribution of the construction sector to regional employment within the non-financial business economy was high in several southern and south-western Member States. Many of these regions have a specialisation in a cluster of activities involving construction, retail trade and transport services, centred on the provision of accommodation and food services, all of which are important in tourism supply. Among the top 20 most specialised regions in construction 11 were Spanish, 6 Italian, 2 Portuguese and 1 was Cyprus (one region at the NUTS 2 level). In all of the 20 most specialised regions the share of construction in the non-financial business economy workforce was at least 16 % and in Castilla-la Mancha (Spain) this share peaked at 21.8 %. It should be noted that no regional employment data for construction is available for France which also traditionally has many regions specialised in construction.

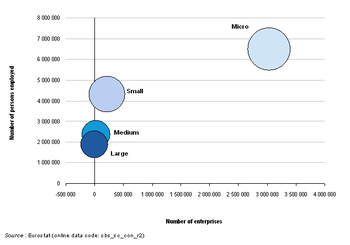

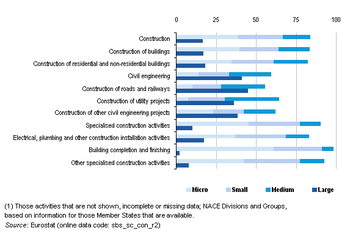

Size class analysis

Most construction enterprises serve a local market and, consequently, the construction sector is characterised by a large number of quite small enterprises and relatively few large ones. Micro and small enterprises (with less than 50 persons employed) together employed 71.8 % of the EU-27's workforce in the construction sector in 2008, a higher share than nearly all of the NACE sections in the non-financial business economy: the average for the non-financial business economy was 49.5 %. Large enterprises (with more than 250 persons employed) provided employment for one eighth of the EU-27’s workforce (12.5 %) in construction, compared with a non-financial business economy average of one third (33.3 %). Most Member States displayed a similar pattern, as in 2008 the combination of micro and small enterprises employed half or more of the construction sector's workforce in all Member States except Bulgaria and Romania where the share was just below this level. The largest contribution by large enterprises was 24.2 % of the workforce in the United Kingdom.

The particularly high share of the construction workforce in micro and small enterprises was elevated by the specialised construction activities subsector, as here 81.5 % of the workforce in the EU-27 was employed in micro and small enterprises in 2008 and just 7.0 % in large enterprises. In contrast, in the civil engineering subsector the combined share of micro and small enterprises was 33.0 % and the share of large enterprises reached 38.5 %; in terms of value added, large civil engineering enterprises contributed an even greater share of the subsector’s total, reaching 40.8 %.

Data sources and availability

The analysis presented in this article is based on the main datasets for structural business statistics (SBS) which are disseminated annually. The three data sets used are:

- the national series which have the most detailed analysis by activity according to the activity classification NACE and the widest range of variables;

- the regional series which provide an analysis at 2-digit level of the regional classification NUTS;

- the size class series which provide an analysis based on five size classes reflecting the number of persons employed.

Context

Construction activity and construction products (structures), have a number of specific characteristics that differentiate them from many other activities and products. Among the most important of these are that the final product is one of the few non-transportable goods, as well as being one of the most durable of human artefacts, forming the physical infrastructure where people live and work. Many construction projects are one-off designs and furthermore the time scale for many projects from conception to completion is typically longer than in many other sectors, and may run to several years. Public procurement is especially important for construction as the public sector is a major purchaser of building and particularly civil engineering work. Construction is one of the most geographically dispersed activities with marked regional differences, and plays a very important economic role in some regions, particularly those associated with tourism, those that are transport and communication hubs, or cultural and sporting centres. Construction is also a highly heterogeneous activity depending on a large number of very different specialisations. The structure of the construction sector can be viewed as a pyramid, with project coordinating enterprises at the top, subcontracting out work to smaller, specialised enterprises in lower tiers.

In many Member States construction activity is seasonal as it is often conducted in the open air or in unfinished structures without heating or air conditioning. Over a longer time period construction is often sensitive to the overall economic cycle. As a provider of tangible assets it typically leads overall economic movements, although this has not been the case following the recent financial and economic crisis where the downturn in construction activity has gone on longer than in many other activities.

One issue that has gained greater visibility in recent years has been the energy efficiency of structures and the sustainability of construction methods. In 2010 the recast energy performance of buildings directive was adopted (replacing a 2002 Directive on the same subject) in order to strengthen the energy performance requirements of the original Directive and to clarify and streamline some of its provisions. Under this Directive, the Member States must apply minimum requirements as regards the energy performance of new and existing buildings, ensure the certification of their energy performance and require the regular inspection of boilers and air conditioning systems in buildings.

In 2011 the construction products Regulation replaced the construction products Directive that was passed in 1989. The Regulation lays down harmonised conditions for the marketing of construction products and forms the central part of the EU legislation for the single market for the construction sector.

Furthermore, in December 2003 a Commission recommendation on Eurocodes was adopted to promote the use of these harmonised methods for calculating the strength of structural construction products. The full set of Eurocodes were published in 2006 and cover 10 design areas: basis of structural design, actions on structures, steel, concrete, composite steel and concrete, timber, masonry and aluminium structures, as well as geotechnical design and seismic design.

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Database

- SBS - industry and construction (sbs_ind_co)

- Annual detailed enterprise statistics - industry and construction (sbs_na_ind)

- Annual detailed enterprise statistics for construction (NACE Rev.2 F) (sbs_na_con_r2)

- Preliminary results on industry and construction, main indicators (NACE Rev.2) (sbs_na_r2preli)

- SMEs - Annual enterprise statistics broken down by size classes - industry and construction (sbs_sc_ind)

- Construction broken down by employment size classes (NACE Rev.2 F) (sbs_sc_con_r2)

- Annual detailed enterprise statistics - industry and construction (sbs_na_ind)

- SBS - regional data - all activities (sbs_r)

- Regional data (NACE Rev.2) (sbs_r_nuts06_r2)

Dedicated section

Other information

- Regulation 58/1997 of 20 December 1996 concerning structural business statistics

- Decision 2367/2002/EC of 16 December 2002 on the Community statistical programme 2003 to 2007

- Regulation 295/2008 of 11 March 2008 concerning structural business statistics

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

External links

- European Commission - Enterprise and Industry, see:

Industrial policy

Construction - European Commission - Energy, see:

Energy efficiency in buildings - Joint research centre, see:

Eurocodes