Archive:Vocational education and training statistics

Data extracted in September 2020.

Planned article update: October 2021.

Highlights

In 2018, 2.6 % of pupils in lower secondary education in the EU-27 followed vocational programmes, with this share reaching 48.4 % for upper secondary education and 94.4 % for post-secondary non-tertiary education.

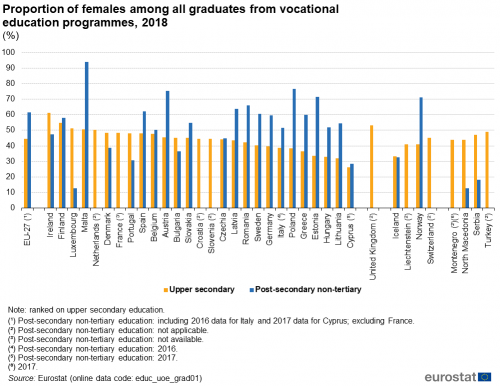

In 2018, 44.6 % of all graduates from vocational programmes in upper secondary education in the EU-27 were female.

In 2015, 30.5 % of enterprises in the EU-27 with 10 or more persons employed had participants in initial vocational training.

Share of females among all graduates from vocational education programmes, 2018

This article presents statistics on vocational training in the European Union (EU) and forms part of an online publication on education and training in the EU. It provides a comprehensive picture of vocational education and training in the EU. The first half of the article analyses vocational education of pupils in schools or similar educational institutions, which may be undertaken as part of secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education. The second part of the article looks at vocational training within enterprises, presenting initial vocational training (IVT) and more detailed information relating to continuing vocational training (CVT) within enterprises. Only enterprises from the business economy are included in the analysis; in other words, most economic activities are covered, with the exclusion of agriculture, forestry and fishing, public administration and defence, compulsory social security, education, human health and social work activities.

Full article

Vocational training within secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education

The first section of this article looks at vocational education within secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education, typically within educational institutions: generally this concerns initial education, before a person enters the labour market for the first time, although it may also include adult education. Within these education levels (which are covered by the international standard classification of education (ISCED) levels 2-4), vocational educational programmes are distinguished from general educational programmes, as they are specifically designed for pupils to acquire the knowledge, skills and competencies for a particular occupation or trade.

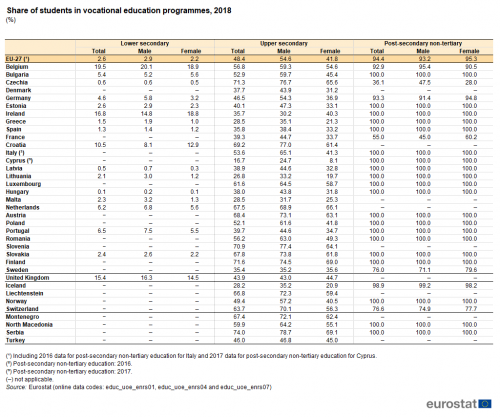

Numbers of pupils

Within lower secondary education (ISCED level 2), vocational programmes are relatively rare: in 2018 they accounted for 2.6 % of the total number of pupils at this level in the EU-27 (note that there were 11 EU Member States where there were no vocational programmes offered within lower secondary education, while the United Kingdom was the only one of the non-member countries included in Table 1 that had vocational programmes at lower secondary education level). A somewhat higher proportion of male than female pupils followed vocational programmes within lower secondary education, as the shares were 2.9 % among male pupils and 2.2 % among female pupils. As can be seen in Table 1, three Member States reported a double-digit share of pupils following vocational programmes within lower secondary education — Croatia, Ireland and Belgium (where a peak of 19.5 % was recorded). While the EU-27 had a higher proportion of male pupils than female pupils in vocational training, this was not the case in Bulgaria, Ireland or Croatia, which were the only Member States that reported a higher proportion of female than male pupils following a vocational programme within lower secondary education.

In 2018, close to half (48.4 %) of all upper secondary (ISCED level 3) school pupils in the EU-27 followed vocational programmes, with the share for males (54.6 %) clearly higher than that recorded for females (41.8 %). In 14 of the EU Member States, less than half of all upper secondary pupils were studying vocational programmes, with this share dropping below one fifth in Cyprus (16.7 %). By contrast, in the Netherlands, Slovakia, Austria and Croatia more than two thirds of upper secondary pupils followed vocational programmes, with even higher shares — 70 % or above — in Slovenia, Czechia and Finland, where a peak of 71.6 % was recorded.

Within post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED level 4), the vast majority of pupils followed vocational programmes, an average of 94.4 % across the EU-27 in 2018 (the average includes 2016 data for Italy and 2017 data for Cyprus). Unlike the two secondary education levels, the share of females (95.3 %) in post-secondary non-tertiary education following vocational programmes was somewhat higher than that for males (93.2 %). In a majority of the EU Member States (17 of the 22 with post-secondary non-tertiary education) all of the pupils at this educational level were enrolled in vocational programmes. Czechia was one of only two Member States where less than half of the total number of pupils within post-secondary non-tertiary education were following vocational programmes (36.1 %). Note there were no post-secondary non-tertiary education pupils in Denmark, Croatia, Malta, the Netherlands or Slovenia.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enrs01), (educ_uoe_enrs04) and (educ_uoe_enrs07)

Graduates from vocational programmes

In 2018, typically between one third and one half of all graduates from upper secondary vocational programmes in the EU Member States were female, with this share averaging 44.6 % across the EU-27. The lowest share was 26.2 % in Cyprus while shares just above 50.0 % were recorded in the Netherlands, Malta and Luxembourg, with somewhat higher rates in Finland (54.8 %) and Ireland (where a peak of 61.3 % was registered).

A similar comparison for post-secondary non-tertiary graduates reveals a wider range between the EU Member States. In 2018, the share of female graduates from vocational programmes was around one eighth (12.7 %) in Luxembourg. By contrast, female graduates accounted for close to three quarters of all post-secondary non-tertiary graduates from vocational programmes in Austria (75.5 %) and Poland (76.6 %) and more than nine tenths (93.9 %) in Malta — see Figure 1.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_grad01)

More information on graduates from secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education is available in a separate article.

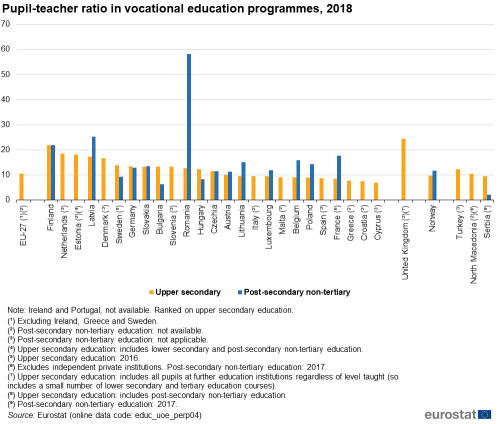

Pupil-teacher ratios for vocational programmes

There was a relatively high degree of variation in pupil-teacher ratios for vocational education programmes across the EU Member States, depending on whether these were at upper secondary level or post-secondary non-tertiary level — see Figure 2. In 2018, the largest difference was recorded in Romania, where the ratio for post-secondary non-tertiary education was4.6 times as high as that recorded for upper secondary education. A similar pattern, although much less marked, was witnessed in France, where the pupil-teacher ratio for post-secondary non-tertiary education in 2017 was 2.1 times as high as that recorded for upper secondary education in 2018. By contrast, there were four Member States (out of 15 for which data are available) where pupil-teacher ratios in vocational programmes were higher for upper secondary education than for post-secondary non-tertiary education. The largest difference among these was reported in Bulgaria, where the pupil-teacher ratio for upper secondary vocational education was 2.1 times as high as that for post-secondary non-tertiary education; the other three Member States were Hungary, Sweden (2016 data for upper secondary education) and Germany.

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_perp04)

Across the EU-27, the pupil-teacher ratio within upper secondary education was 1.5 percentage points higher for general programmes (12.0 pupils per teacher) than for vocational programmes (10.5). There was no clear pattern across the EU Member States, as among the 25 for which recent data are available in 2018 (Ireland and Portugal, not available; Sweden, 2016 data), there were 12 with higher pupil-teacher ratios for vocational programmes and 12 with higher ratios for general programmes; in Czechia the ratios were the same for general and vocational programmes. The largest differences were in Denmark, Finland and Latvia, as each of these recorded pupil-teacher ratios for vocational programmes that were 6.8-8.7 pupils higher than for general programmes.

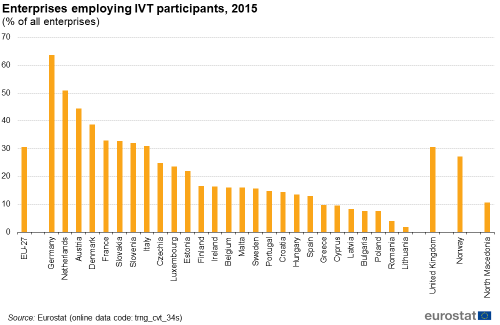

Initial vocational training in enterprises

Although the data presented in Figure 3 are from the continuing vocational training survey (CVTS), they show the proportion of enterprises providing initial vocational training (IVT), rather than continuing vocational training (CVT); a detailed description of these terms is provided below in the key concepts section under Data sources. In 2015, almost one third (30.5 %) of all enterprises with 10 or more persons employed in the EU-27’s business economy provided IVT, although the proportion varied greatly across EU Member States. Only eight Member States reported a share that was above the EU-27 average, with around a third of all enterprises in Italy, Slovenia, Slovakia, France and Denmark providing IVT, more than two fifths in Austria, around one half in the Netherlands, and more than three fifths in Germany. At the other end of the scale, less than 1 in 10 enterprises provided IVT in seven of the Member States, principally Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007, but also Greece.

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_34s)

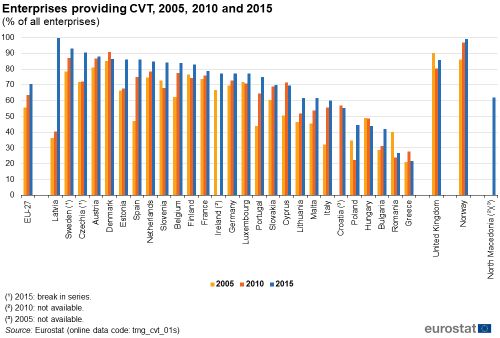

Continuing vocational training in enterprises

The remainder of this article focuses on data from the continuing vocational training survey and in particular on the provision of continuing vocational training (CVT) by enterprises. This information refers to education or training activities which are financed, at least in part, by enterprises; part financing could include, for example, the use of work time for the training activity. CVT can be provided either through dedicated courses or other forms of CVT, such as guided on-the-job training. In general, enterprises finance CVT in order to develop the competences and skills of the people they employ, hoping that this may contribute towards increasing competitiveness and productivity. A large majority of CVT is non-formal education or training, in other words, it is provided outside the formal education system.

In 2015, 70.5 % of enterprises employing 10 or more persons in the EU-27 provided CVT to their staff (see Figure 4); this marked an increase compared with 2005 and 2010 when the corresponding shares were 55.6 % and 63.6 % respectively. Among the EU Member States, the share of enterprises that provided such training in 2015 ranged from 21.7 % in Greece to 99.9 % in Latvia; note that this share was also very high in Norway (99.1 %).

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_01s)

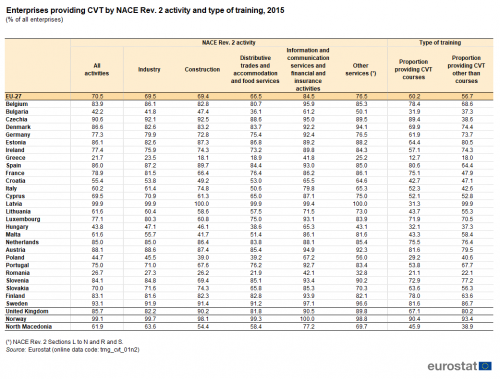

Enterprises providing continuing vocational training by economic activity

Table 2 provides a more detailed analysis of the proportion of enterprises providing CVT. Within the EU-27, enterprises in services (other than distributive trades or accommodation and food services) were more likely to offer CVT. This was particularly the case for the grouping of information and communication services and financial and insurance activities where the proportion of enterprises offering CVT peaked at 84.5 %.

In 24 EU Member States, the highest proportion of enterprises providing CVT was recorded for information and communication services and financial and insurance activities. In the remaining three Member States — Denmark, Latvia and Lithuania — the highest shares were recorded for other services, which includes for example real estate activities, professional, scientific, technical, administrative and support service activities, arts, entertainment and recreation; Latvia also reported that 100 % of its construction enterprises provided CVT. The same pattern as for the vast majority of EU Member States was repeated in the United Kingdom, Norway and North Macedonia, where the highest proportion of enterprises providing CVT was recorded for information and communication services and financial and insurance activities.

Enterprises in the EU-27 were slightly more likely to provide CVT through courses (either internal or external) than to provide other forms of CVT, such as planned learning through guided on-the-job training, job rotation, exchanges or secondments, conferences and workshops, participation in learning or quality improvement groups, or self-directed learning. In 2015, 60.2 % of EU-27 enterprises offered at least CVT courses and 56.7 % provided at least other forms of CVT; note that some of these enterprises provided both CVT courses and other forms of CVT. The proportion of enterprises providing CVT courses exceeded 80.0 % in Czechia, Austria, Sweden and Spain and was also above the EU-27 average in Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, France, Slovenia, Luxembourg, Denmark, Estonia, Slovakia and Germany; it was even higher in Norway (at 90.4 %). By contrast, less than one quarter of enterprises provided CVT courses in Romania and Greece. The proportion of enterprises providing other forms of CVT had a slightly wider range, from below one quarter in Greece and Romania up to more than four fifths in Estonia and Sweden, peaking at 99.9 % in Latvia; the share recorded in Norway was again relatively high (at 93.4 %).

Comparing the proportion of enterprises providing CVT courses and those providing other forms of CVT, differences in excess of 10 percentage points were observed in 12 of the EU Member States, with enterprises in Finland, Spain, France and Czechia more likely to provide CVT courses, whereas enterprises in Poland, Lithuania, Germany, Portugal, Malta, Estonia, Ireland and Latvia were more likely to provide other forms of CVT.

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_01n2)

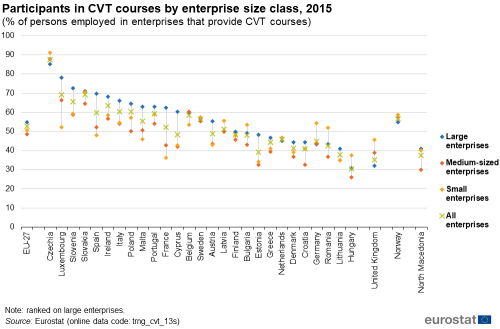

Participation rates for continuing vocational training courses

The data on participation rates in Figure 5 only relate to participation in CVT courses and not to participation in other forms of CVT. On average, enterprise size appears to be a relatively minor factor influencing the provision of CVT courses across the EU-27: in 2015, more than half (54.8 %) of all persons employed in large enterprises (with 250 persons employed or more) participated in CVT courses, compared with 48.5 % for medium-sized enterprises (with 50-249 persons employed) and 50.6 % of those employed by small enterprises (with 10-49 persons employed); see Figure 5. It is interesting to note that in seven of the EU Member States the highest participation rates were reported for small enterprises, while small enterprises and medium-sized enterprises in the Netherlands recorded the joint highest rates. The most notable example was Germany as participation rates for CVT courses in 2015 were more than 10 percentage points higher among small enterprises than they were among large enterprises.

(% of persons employed in enterprises that provide CVT courses)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_13s)

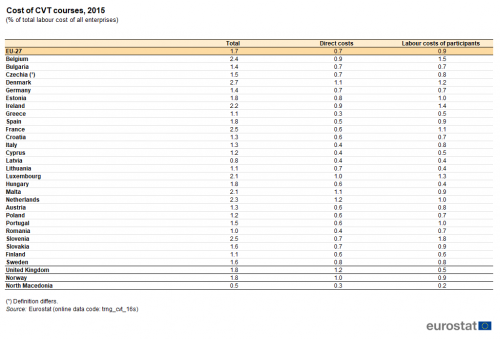

Cost of continuing vocational training courses

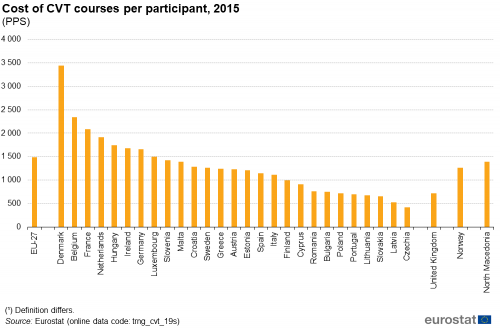

As for CVT participation rates, data on the cost of CVT only relate to CVT courses and not to other forms of CVT. The data on the cost of CVT courses (as shown in Figure 6) have been converted to purchasing power standards (PPS) rather than presenting these costs in euros; purchasing power standards are an artificial currency which adjusts for price level differences between countries.

In 2015, the average expenditure on CVT courses by enterprises in the EU-27 was 1 484 PPS per participant; note that each person is only counted once, regardless of how many courses they attend during a year and regardless of the course duration. The average expenditure per participant on CVT courses ranged from 426 PPS in Czechia to 1 912 PPS in the Netherlands, with France (2 081 PPS), Belgium (2 337 PPS) and Denmark (3 439 PPS) above this range. Among the 10 EU Member States where average expenditure per participant was below 1 000 PPS, eight were Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007, with Portugal and Finland the only exceptions.

The overall costs incurred by enterprises for the provision of CVT courses correspond to total monetary expenditure. This total is composed of direct costs, participants’ labour costs and net contributions, where the latter is the balance between contributions to and receipts from training funds. In 2015, total training costs for EU-27 enterprises represented an average of 1.7 % of total labour costs (see Table 3); just over half of this figure (0.9 %) represented participants’ labour costs, and most of the rest (0.7 %) was direct costs. Latvia was the only EU Member State where the cost of CVT courses in 2015 was less than 1.0 % of total labour costs (this situation was also recorded in North Macedonia; 0.5 %), while this ratio exceeded 2.0 % in Luxembourg, Malta, Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Slovenia and Denmark.

(% of total labour cost of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_16s)

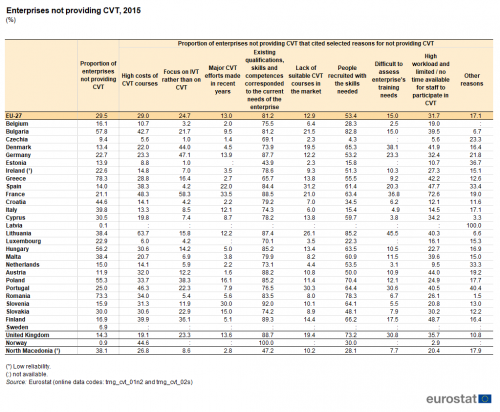

Reasons for enterprises not providing training

As noted above, 70.5 % of EU-27 enterprises provided CVT (including courses and other forms) in 2015 and therefore 29.5 % did not (as shown in Table 4). The two main reasons given by enterprises in the EU-27 for not providing CVT related to recruitment strategies: more than half (53.4 %) of those enterprises not providing CVT did not do so because they tried to recruit people with the required skills while more than four fifths (81.2 %) said that the existing skills and competences of their workforce already corresponded to their needs. A lack of time and the high cost of CVT were the third and fourth most common reasons, given by around 3 in 10 enterprises not providing training.

Among nearly all of the EU Member States, the most common reasons for enterprises not to provide CVT were that the existing skills and competences of their workforce already corresponded to the enterprise’s needs or that they tried to recruit people with the required skills. In 2015, the only exceptions to this pattern were in: Czechia, Estonia and Italy, where the residual category of ‘other reasons’ was the second most common reason; and France which reported a lack of time as the second most common reason, with trying to recruit people with the required skills becoming the third most common reason.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Sources

The standards for international statistics on education are set by three international organisations:

- the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) institute for statistics (UIS);

- the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD);

- Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union.

Two principal sources of data are used in this article:

- a joint annual UNESCO/OECD/Eurostat (UOE) data collection on education statistics which forms the basis for the core components of Eurostat’s database on education statistics; data concerning vocational programmes in initial education are presented in this article;

- data from the five-yearly continuing vocational training survey (CVTS) which collects information on enterprises’ efforts in the continuing vocational training of their workforce; the most recent year for which data are available is 2015; the coverage is enterprises with 10 or more persons employed in NACE Rev. 2 Sections B to N, R and S (excluding therefore agriculture, forestry and fishing, public administration and defence, compulsory social security, education, human health and social work activities).

More information about these sources is available in the following articles:

- methodology of the UNESCO-OECD-Eurostat data collection;

- methodology of the continuing vocational training survey (CVTS).

Classification

The international standard classification of education (ISCED) provides the basis for the classification of education statistics, describing different levels of education; it was first developed in 1976 by UNESCO and revised in 1997 and 2011. ISCED 2011 distinguishes nine levels of education: early childhood education (level 0); primary education (level 1); lower secondary education (level 2); upper secondary education (level 3); post-secondary non-tertiary education (level 4); short-cycle tertiary education (level 5); bachelor’s or equivalent (level 6); master’s or equivalent (level 7); doctoral or equivalent (level 8). The first statistics based on ISCED 2011 were published in 2015 starting with data for the 2013 reference period. Within ISCED 2011, two categories of programme orientation are identified for ISCED levels 2-5, namely, general and vocational educational programmes.

Key concepts

UOE concepts

Vocational education programmes are designed for learners to acquire the knowledge, skills and competencies specific to a particular occupation, trade, or class of occupations or trades. Vocational education may have work-based components (such as apprenticeships or traineeships). Successful completion of such programmes leads to labour market-relevant vocational qualifications acknowledged as occupationally-oriented by the relevant national authorities and/or the labour market.

A graduate is an individual who has successfully completed an education programme.

Pupil-teacher ratios are calculated by dividing the number of full-time equivalent pupils in each level of education by the number of full-time equivalent teachers at the same level; this ratio should not be confused with average class size, which refers to the number of pupils in a given course or classroom.

Continuing vocational training concepts

CVT in enterprises concerns training measures or activities which have as their primary objective the acquisition of new competences or the development and improvement of existing ones. CVT in enterprises must be financed, at least in part, by the enterprise and should concern persons employed by the enterprise (either those with a work contract or those who work directly for the enterprise such as unpaid family workers). Persons employed holding an apprenticeship or training contract should not be taken into consideration for CVT. The training measures or activities must be planned in advance and must be organised or supported with the special goal of learning. Random learning and initial vocational training (IVT) are explicitly excluded.

CVT courses are typically clearly separated from the active workplace (learning takes place in locations specially assigned for learning like a classroom or training centre). They show a high degree of organisation (time, space and content) by a trainer or a training institution. The content is designed for a group of learners (for example a curriculum exists), while two distinct types of courses may be identified — internal and external CVT courses.

Other forms of CVT are typically connected to active work and the active workplace, but they can also include participation (instruction) in conferences, trade fairs and similar events for the purpose of learning. These other forms of CVT are often characterised by a degree of self-organisation (time, space and content) by the individual learner or by a group of learners. The content is often tailored according to the learners’ individual needs in the workplace. The following types of other forms of CVT may be identified:

- planned training through guided on-the-job training;

- planned training through job rotation, exchanges, secondments or study visits;

- planned training through participation (instruction received) in conferences, workshops, trade fairs and lectures;

- planned training through participation in learning or quality circles;

- planned training through self-directed learning/e-learning.

A participant in CVT courses is a person who has taken part in one or more CVT courses during the reference year. Each person should be counted only once, irrespective of the number of CVT courses he or she has participated in.

The costs of CVT courses cover direct costs, participants’ labour costs and the balance of contributions (net contribution) to and receipts from training funds.

Direct course costs:

- fees and payments for CVT courses;

- travel and subsistence payments related to CVT courses;

- the labour costs of internal trainers for CVT courses (direct and indirect costs); and

- the costs for training centres, training rooms and teaching materials.

Participants’ labour costs include the labour costs of participants for CVT courses that take place during paid working time.

The net contribution to training funds is made up of the cost of contributions made by the enterprise to collective funding arrangements through government and intermediary organisations minus receipts from collective funding arrangements, subsidies and financial assistance from government and other sources.

The CVTS also collects some information on initial vocational training (IVT) within enterprises which is defined as a formal education programme or a component of it where the working time of the paid apprentices/trainees alternates between periods of practical training in the workplace and general/theoretical education in an educational institution or training centre. For 2015, the coverage was training within ISCED levels 2-5, in other words, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education as well as short-cycle tertiary education. The length of IVT should be between six months and six years. Voluntary apprenticeships/traineeships are excluded.

| Tables in this article use the following notation: | |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

| – | not applicable. |

Context

Copenhagen process and European initiatives

Since 2002, national authorities and social partners from European countries have taken part in the Copenhagen process which aims to promote and develop vocational education and training (VET) systems; at the time of writing 33 countries are active in this process. In June 2010, the European Commission presented its proposals for ‘a new impetus for European cooperation in vocational education and training to support the Europe 2020 strategy’ (COM(2010) 296 final). In December 2010, in Bruges (Belgium) the priorities for the Copenhagen process for 2011-2020 were set, establishing a vision for vocational education and training. For more information, see the article on Education and training statistics introduced.

Europe 2020 and ET 2020 strategies

The conclusions of the November 2010 Council underlined the need for data on VET systems in the context of the Copenhagen process and the important contribution VET systems can potentially make to the Europe 2020 strategy. In particular, the Bruges communiqué states that ‘policy-making in VET should be based on existing comparable data. To this end, and using the lifelong learning programme, Member States should collect relevant and reliable data on VET — including VET mobility — and make these available for Eurostat. Member States and the European Commission should jointly agree on which data should be made available first’.

The strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (known as ET 2020), was adopted by the Council in May 2009. It sets out four strategic objectives for education and training in the EU:

- making lifelong learning and mobility a reality;

- improving the quality and efficiency of education and training;

- promoting equality, social cohesion and active citizenship; and

- enhancing creativity and innovation (including entrepreneurship) at all levels of education and training.

The ET 2020 strategy set a number of benchmarks to be achieved by 2020, including that an average of at least 15 % of adults aged 25 to 64 should participate in lifelong learning. Two supplementary benchmarks on learning mobility were adopted by the Council in November 2011, including one that, by 2020, an EU average of at least 6 % of 18 to 34 year-olds with an initial vocational education and training (VET) qualification should have had an initial VET-related study or training period (including work placements) abroad lasting a minimum of two weeks, or less if documented by Europass.

Recovery Plan for Europe

Vocational education and training as well as skills are part of the European Commission’s COVID-19 recovery efforts in the fields of employment and social policy and contribute to the Recovery Plan for Europe. In June 2020 a Communication on a European Skills Agenda for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience was adopted. This puts forward 12 actions to support partnerships for skills, up- and reskilling and empowering lifelong learning.

Erasmus+

The Erasmus programme was one of the most well-known European programmes and ran for just over a quarter of a century; in 2014 it was superseded by the EU’s programme for education, training, youth and sport, referred to as ‘Erasmus+’. It is expected that four million people will benefit from Erasmus+, including around 650 thousand vocational training and education students. The programme currently covers all 27 EU Member States, as well as the United Kingdom (at least until 31 December 2020), Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey.

In May 2018, the European Commission adopted proposals for the Erasmus programme for 2021-2027, involving a doubling of the budget to EUR 30 billion which it is expected should enable 12 million people to participate in the programme. In June 2019, the European Parliament approved the budget for the programme for 2021-2027.

Direct access to

- Participation in education and training (t_educ_part)

- Education and training outcomes (t_educ_outc)

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Pupils and students - enrolments (educ_uoe_enr)

- Continuing vocational training in enterprises (trng_cvt)

- Education personnel (educ_uoe_per)

- Teachers and academic staff (educ_uoe_perp)

- Education and training outcomes (educ_outc)

- Graduates (educ_uoe_grad)

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

Metadata

- Education administrative data from 2013 onwards (ISCED 2011) (ESMS metadata file — educ_uoe_enr_esms)

- Continuing vocational training in enterprises (ESMS metadata file — trng_cvt_esms)

Manuals and other methodological information

- Classification of learning activities — Manual — 2016 edition

- Further methodological information on the CVTS

- International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED)

- ISCED 2011 operational manual — Guidelines for classifying national education programmes and related qualifications

- UOE data collection on formal education — Manual on concepts, definitions and classifications — 2019 edition

- For information on legislation see EU legislation on education and training statistics

- CEDEFOP — European centre for the development of vocational training

- CEDEFOP — VET toolkit for tackling early leaving

- European Commission — Education and training — Adult learning

- European Commission — Education and training — Strategic framework for education and training

- European Commission — Education and training — Vocational education and training

- European Commission — Education and training monitor

- European Commission — Programmes — Erasmus+

- Eurydice — Better knowledge for better education policies

- OECD — Skills beyond school

- OECD — OECD policy reviews of vocational education and training (VET) and adult learning

- UNESCO — Institute for lifelong learning

- UNESCO — Strategy for technical and vocational education and training (TVET) (2016-2021)