National accounts and GDP

Data extracted in June 2024.

Planned article update: June 2025.

Highlights

In 2023, EU real GDP was 0.5% higher than in 2022.

In 2023, increases were recorded for most expenditure components of GDP, but there was a fall in gross capital formation.

Real GDP rate of change, 2005–23

National accounts are the source for a multitude of well-known economic indicators that are presented in this article. Gross domestic product (GDP) is the most frequently used measure for the overall size of an economy. Derived indicators such as GDP per inhabitant (per capita) – for example, in euro or adjusted for differences in price levels (as expressed in purchasing power standards, PPS) – are widely used for a comparison of living standards; they are also used to monitor economic convergence or divergence within the European Union (EU).

Moreover, the development of specific GDP components and related indicators, such as those for economic output, imports and exports, domestic (private and public) consumption or investments, as well as data on the distribution of income and savings, can give valuable insights into the main drivers of economic activity. These can serve as the basis for the design, monitoring and evaluation of specific EU policies.

This article is published every year with annual data. This 2024 edition describes the situation from 2005 up to (and including) the year 2023. As a consequence, the time series covers the global financial and economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and much of the cost-of-living crisis. While these crises have impacted the economy as a whole, they have impacted various sectors differently as well as differing in terms of the type of expenditure, such as consumption and investment. This should be borne in mind when analysing time series, for example when comparing data for the most recent years – 2020 to 2023 – with each other and with data for 2019 and earlier years.

Full article

Developments for GDP in the EU: the rebound observed in 2021 continued in 2022 and 2023, but was progressively more subdued

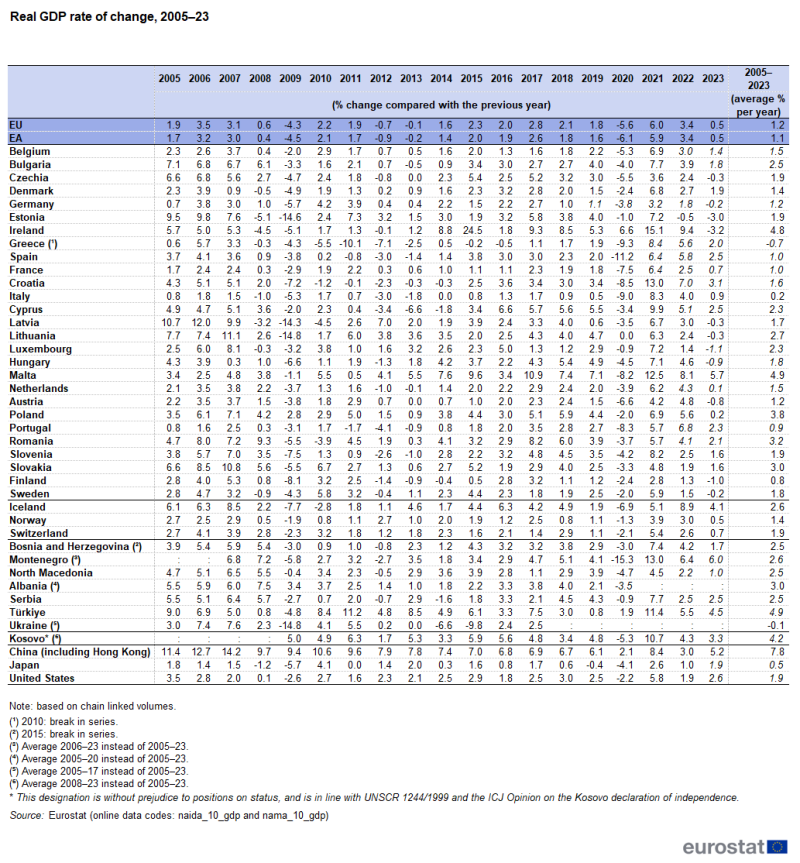

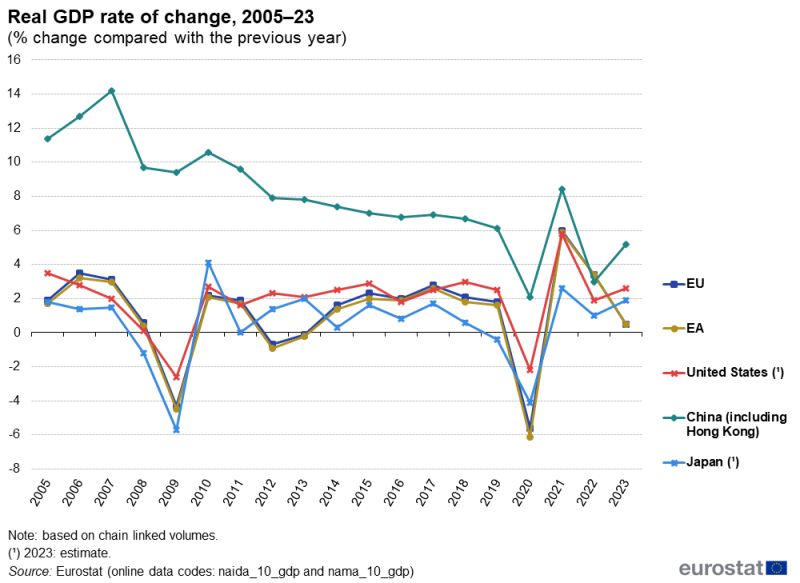

The global financial and economic crisis resulted in a severe recession in the EU in 2009 (see Figure 1), followed by a recovery in 2010. The crisis started earlier in Japan, with a negative annual rate of change for GDP (in real terms) already recorded in 2008, a deepening in 2009 and a rebound in 2010. By contrast, economic output in China (including Hong Kong) continued to grow at a rapid pace during the global financial and economic crisis (close to 10% each year), slowing somewhat in subsequent years, but remaining considerably higher than in any of the other economies shown in Figure 1 for almost every year.

The global financial and economic crisis was already apparent in the EU in 2008 when there had been a considerably lower rate of increase for GDP than in 2007 (down from 3.1% in 2007 to 0.6% in 2008) and this was followed by a 4.3% decrease in GDP in 2009. The recovery in the EU saw the index of GDP (based on chain linked volumes) increase 2.2% in 2010 and there was a further gain of 1.9% in 2011. The recovery wasn’t sustained; GDP contracted 0.7% in 2012 and the change in 2013 was negligible (down 0.1%). A series of positive rates of change was recorded thereafter, with growth relatively stable between 1.6% and 2.8% each year from 2014 to 2019. In 2020, the EU recorded a real decrease in GDP of 5.6% as the initial impact of the COVID-19 crisis was felt; this was considerably larger than the decrease in activity in 2009 during the global financial and economic crisis. Equally, the rebound in activity in 2021, up 6.0%, was stronger than that observed in 2010, while there were further, more subdued expansions in 2022 and 2023, up 3.4% and 0.5%, respectively.

In the euro area, the corresponding rates of change were similar to those recorded in the EU: the contractions recorded in 2009, 2012, 2013 and 2020 were stronger (down by 4.5%, 0.9%, 0.2% and 6.1%) than in the EU. While there was growth in the euro area each year that there was growth in the EU, the rate of growth in the euro area was consistently 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points lower, with 2 exceptions: the increases in 2022 and 2023 were equally as strong in the euro area (up 3.4% and 0.5%) as in the EU. As such, during the period 2005–23, real GDP growth in the euro area (up 21.0% overall) was weaker than that in the EU as a whole (up 24.8%).

(% change compared with the previous year)

Source: Eurostat (naida_10_gdp) and (nama_10_gdp)

Within the EU, real GDP growth varied considerably, both over time and between EU countries (see Table 1). After a contraction in 2009 in all of the EU countries except for Poland, economic growth returned thereafter in most of the EU countries: 23 recorded growth in 2010 and (a different) 23 recorded growth in 2011. However, in 2012 this development changed, as just over half (14) of the EU countries reported economic expansion. Thereafter, a larger majority of EU countries once again recorded growth, with the number of countries recording a positive rate of change reaching 15 in 2013 and rising to 23 in 2014 and 26 in 2015 and 2016. All 27 EU countries recorded a positive rate of change in 2017 (the 1st time this had occurred since 2007) and did so again in 2018 and 2019.

With the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, the situation changed greatly.

- In 2020, Ireland was the only EU country to record GDP growth while there was no change in Lithuania. The negative rates of change elsewhere ranged down to 7.5% in France, 8.2% in Malta, 8.3% in Portugal, 8.5% in Croatia, 9.0% in Italy, 9.3% in Greece and 11.2% in Spain.

- The rebound in 2021 was experienced in all of the EU countries which had recorded falls in 2020, with rates of growth ranging from 2.8% in Finland to 9.9% in Cyprus, 12.5% in Malta and 13.0% in Croatia. Ireland also experienced growth in 2021, up 15.1%.

- In 2022, Estonia recorded a decrease of 0.5%, while all other EU countries continued to record growth. Ireland again recorded the fastest growth, up 9.4%. Austria and Portugal were the only EU countries to record faster growth in 2022 than in 2021.

- In 2023, the rates of change were much more mixed. The rebound from the COVID-19 crisis tailed off and the cost-of-living crisis had an impact.

- Growth was recorded in 16 EU countries, with the fastest growth in Malta (up 5.7%).

- Among the 11 EU countries where GDP contracted, the sharpest falls were in Ireland (down 3.2%) and Estonia (down 3.0%).

- All EU countries recorded a lower rate of change in 2023 than in 2022.

- Ireland recorded its 1st annual decrease in GDP in 2023, after 10 consecutive annual increases. In a similar manner, Lithuania also recorded a decrease in 2023, the 1st since 2009.

Average annual GDP growth of 1.2% over the last 18 years in the EU and 1.1% in the euro area

The effects of the global financial and economic crisis lowered the overall performance of the EU country economies when analysing developments over the last 18 years, and the COVID-19 crisis lowered it further still. The annual average growth rates of GDP in the EU and the euro area between 2005 and 2023 were 1.2% and 1.1%, respectively (see Table 1). By comparison, between 2010 (the 1st year after the low point of the global and financial crisis) and 2019 (the last full year before the COVID-19 crisis) the average for the EU was 1.5% and for the euro area it was 1.3%.

The highest growth rates among the EU countries, by this measure, were recorded for Malta (average annual growth for GDP of 4.9% between 2005 and 2023) and Ireland (4.8%; this includes an exceptional increase in 2015 reflecting the activities of multinational enterprises). Poland (3.8%), Romania (3.2%) and Slovakia (3.0%) had the next highest average growth rates. By contrast, the real development of GDP between 2005 and 2023 was negative overall in Greece, down on average 0.7% per year.

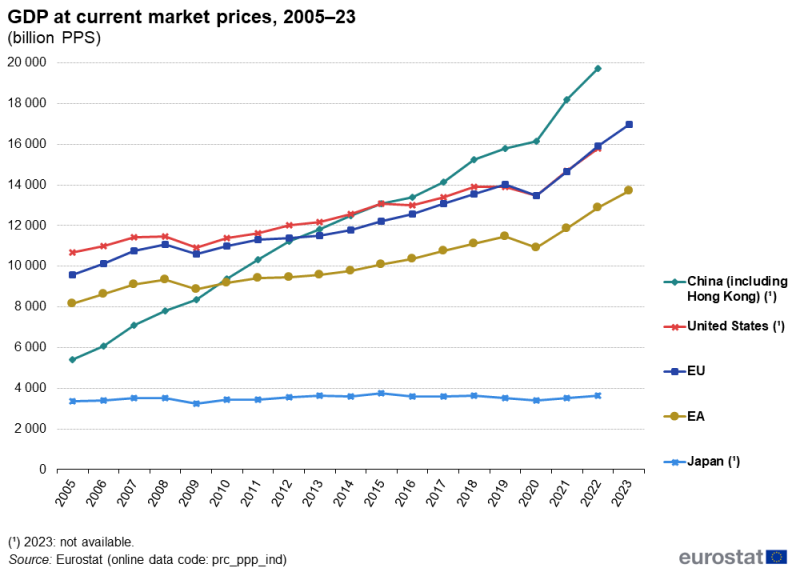

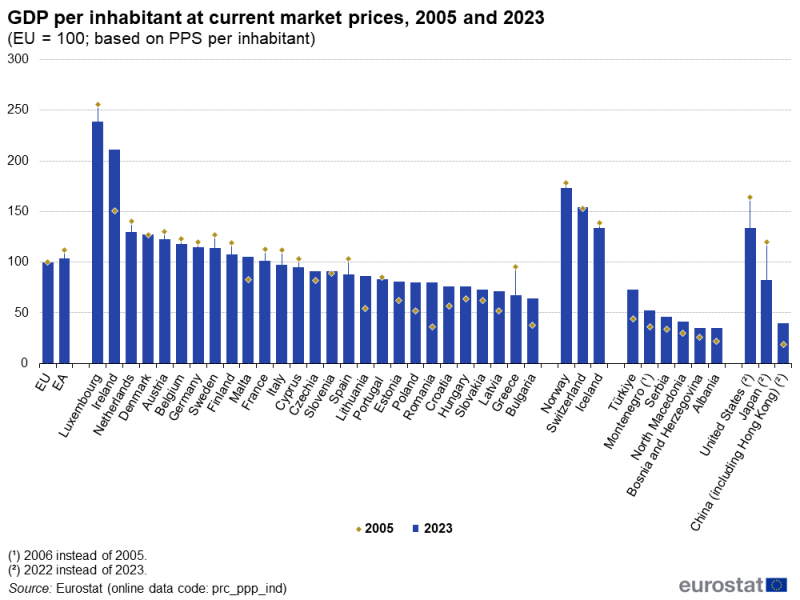

Cross-country comparisons are often made using purchasing power standards (PPS) which are values adjusted to account for differences in price levels between countries. Note that the data shown in Figures 2 and 3 and in Table 2 are in current prices and shouldn’t be used for calculating rates of change because of inflation and exchange rate fluctuations.

In 2023, GDP in the EU was 17.0 trillion PPS (17 000 billion PPS) – note that 1 PPS equals 1 euro (€) for the EU. PPS figures are intended for cross-country comparisons rather than for temporal comparisons since they can’t be considered as time series for methodological reasons. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that China historically had a lower level of economic output than either the EU or the United States, but that this situation changed with the rapid transformation and continued expansion of the Chinese economy. China’s GDP in PPS reached a level in 2013 that was – for the 1st time – higher than that recorded for the EU. In 2015, China’s GDP in PPS surpassed that of the United States.

In 2023, Germany accounted for more than a fifth of the EU’s GDP in PPS terms

The euro area accounted for 80.9% of the EU’s GDP in 2023 (when measured in PPS terms), down from 85.4% in 2005. In 2023, the sum of the 4 largest EU economies (Germany, France, Italy and Spain) accounted for just under three fifths (59.1%) of the EU’s GDP (in PPS terms), which was 5.1 percentage points lower than their combined share 18 years earlier (in 2005). Germany alone accounted for 21.6% of the EU’s GDP in 2023, down from 22.4% in 2005. The shares of the 3 other large EU countries fell more strongly between 2005 and 2023, down 2.2 points in Italy, 1.1 points in France and 0.9 points in Spain.

In 2023, GDP per inhabitant averaged €37 610 across the EU

To evaluate standards of living, it is commonplace to use GDP per inhabitant, in other words, adjusted for the size of an economy in terms of its population: the population of the EU in 2023 was 451 million. In 2023, average GDP per inhabitant for the EU (in current prices) was €37 610. Values expressed in PPS have been adjusted for differences in price levels across countries. The relative position of individual countries can be expressed through a comparison with the EU average, with this set to equal 100 (see the right-hand side of Table 2). Based on this measure, the highest value among the EU countries was recorded for Luxembourg, where GDP per inhabitant in PPS was 2.39 times as high as (or 239% of) the EU average in 2023; this is partly explained by the relatively large number of cross-border workers from Belgium, France and Germany. By contrast, GDP per inhabitant in PPS in Bulgaria was just under two thirds (64%) the EU average.

A comparison of the PPS figures relative to the EU for 2005 and 2023 suggests that some convergence in living standards took place

- most countries that joined the EU in 2004, 2007 or 2013 moved from a position some way below the EU average in 2005 to a position closer to the EU average in 2023, despite some setbacks during the various crises – see Figure 3

- most of the remaining Nordic and western EU countries – Belgium, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Finland, France, Sweden and Luxembourg – moved downwards from a position above the EU average in 2005 to a position closer to (but still above) the EU average in 2023; for example, France moved from 113% of the EU average in 2005 to 101% of the average in 2023.

Denmark was an exception to the second of these developments, as its ratio compared with the EU average stayed the same (127% of the EU average in both years) and Ireland was also an exception as it moved further ahead of the EU average (from 151% to 211%).

The other countries which did not follow either of the broad developments were the southern EU countries

- Malta not only moved closer to the EU average, but above it (83% of the EU average in 2005 and 105% in 2023)

- Cyprus moved from above the EU average (103% in 2005) to a position below it (95% in 2023)

- Italy and Spain also moved from positions above the EU average (112% and 103%) to positions below it (97% and 88%)

- Greece (from 95% to 67%) and Portugal (from 85% to 83%) moved further below the EU average.

(EU = 100; based on PPS per inhabitant)

Source: Eurostat (prc_ppp_ind)

Gross value added in the EU analysed by economic activity

Close to three quarters of the EU’s total value added in 2023 was generated within services

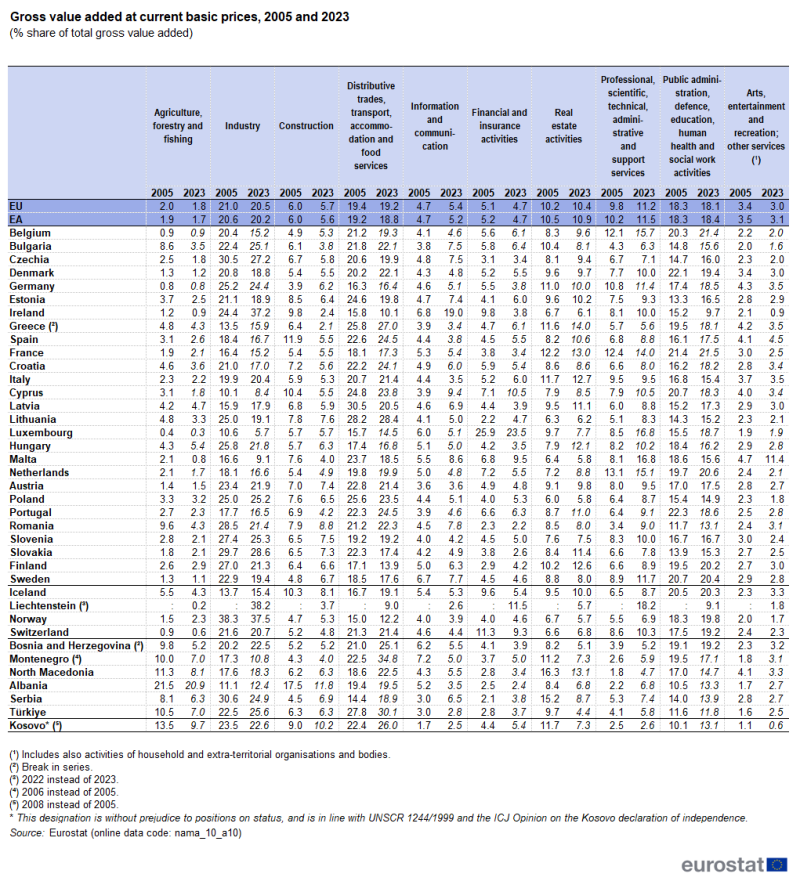

Looking at GDP from the output side, Table 3 gives an overview of the relative importance of 10 economic activities (as defined by NACE Rev. 2) in terms of their contribution to total gross value added at current basic prices.

Between 2005 and 2023, the 3 largest activities in the EU experienced a fall in their share of total value added: industry’s share declined from 21.0% in 2005 to 20.5% in 2023; the contribution of distributive trades, transport, accommodation and food services fell from 19.4% to 19.2%; and the share of public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities also decreased marginally, from 18.3% to 18.1%.

Professional, scientific, technical, administrative and support services increased its share of value added by 1.3 percentage points between 2005 and 2023, the largest percentage point increase recorded among the 10 activities shown; it moved to become the 4th largest activity with an 11.2% share. Real estate activities dropped from 4th to 5th largest despite a small increase in its share to 10.4%. The 2nd largest increase was observed for the share of information and communication activities, up from 4.7% to 5.4%, moving ahead of financial and insurance activities.

The remaining activities recorded falls in their share of output in the EU between 2005 and 2023: the share for agriculture, forestry and fishing was down slightly, to 1.8%; construction was down from 6.0% to 5.7%; the share for financial and insurance activities was down from 5.1% to 4.7%; a similar sized fall was also observed for arts, entertainment and recreation, other services and activities of household and extra-territorial organisations and bodies, down from 3.4% to 3.0%.

(% share of total gross value added)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_a10)

Services contributed 71.9% of the EU’s total gross value added in 2023 compared with 71.0% in 2005. The relative importance of services was particularly high in Luxembourg, Malta, Cyprus, Belgium, Greece, France, Portugal, the Netherlands and Spain, where they accounted for at least three quarters of total value added. By contrast, the share of services was below two thirds in Hungary, Romania, Czechia, Slovenia, Poland and Slovakia, and was as low as 59.5% in Ireland; all of these EU countries recorded relatively high shares for industry, particularly Ireland.

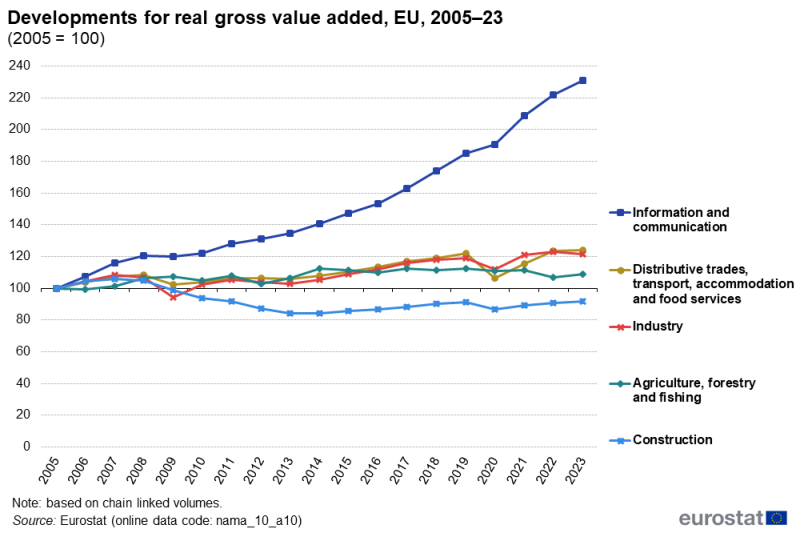

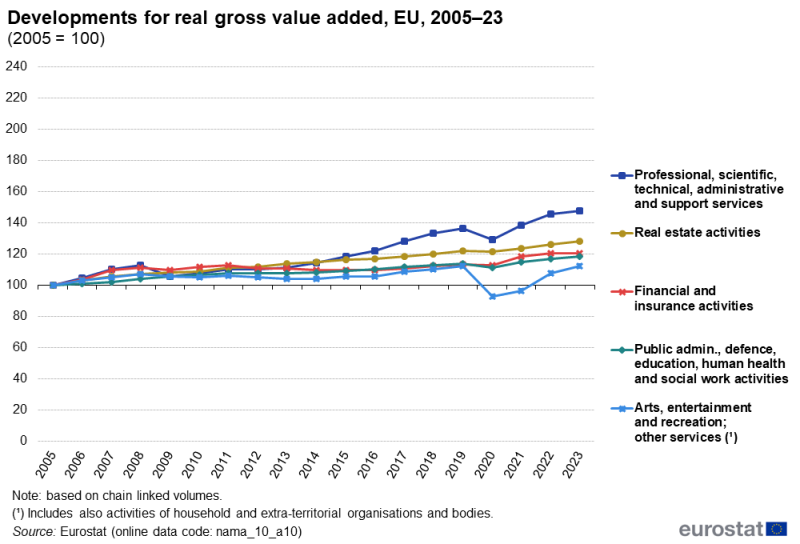

Diverging developments of economic activities interrupted by the global financial and economic crisis and the COVID-19 crisis

Structural change in the EU is, at least in part, a result of phenomena such as technological change, developments in relative prices, outsourcing and globalisation, often resulting in manufacturing activities and some services (those that can be provided remotely, such as online or through call centres) being moved to lower labour-cost regions, both within and outside the EU. Furthermore, several activities were particularly affected by the global financial and economic crisis and its aftermath, the COVID-19 crisis and/or by the cost-of-living crisis; any recovery from the more recent crises has been uneven when analysed in terms of developments for real gross value added by activity.

- Information and communication activities recorded growth nearly every year between 2005 and 2023, the only exception was a fall of 0.6% in 2009. Furthermore, this was the only activity among those shown in Figures 4 and 5 that recorded growth in 2020, expanding by 2.9%. Output from information and communication activities more than doubled (up 131.1%) between 2005 and 2023, by far the largest growth among all 10 activities.

- The development for distributive trades, transport, accommodation and food services shows a clear interruption in 2020. A relatively strong fall in 2009 (down 5.3%) and a much weaker fall in 2013 (down 0.5%) were the only negative rates of change before 2020. The 12.8% fall in 2020, largely reflecting the COVID-19 containment measures, was the 2nd largest fall in 2020 among the 10 activities; equally, the rebound from 2021 to 2023 (up 16.0% combined) was the 3rd largest among the 10 activities. Looking at the whole period from 2005 to 2023, overall growth was 23.8%.

- Industrial output increased prior to the global financial and economic crisis but fell 1.4% in 2008 and 11.8% in 2009. After a strong rebound in 2010 and 2011 (up 12.0% overall), industrial output fell by 2.6% between 2011 and 2013. Thereafter, industrial output increased consistently, with growth recorded for 6 consecutive years. This period of growth was followed by a decline of 5.9% in 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic and its related restrictions had an impact. Output rebounded 8.2% in 2021 and 1.6% in 2022, before a further contraction in 2023 (down 1.3%). Overall, industrial output was 21.4% higher in 2023 than in 2005.

- Between 2005 and 2009, output from agriculture, forestry and fishing increased by 7.3%. Thereafter its development fluctuated for 3 years before increasing in 2013 and 2014. More recent years have again shown fluctuating developments, but with little volatility, with rates of change between -1.5% and 2.3%; 2022 was a notable exception, as output fell 4.1%. Agriculture, forestry and fishing reported the smallest increase in 2021 (up 0.6%) and was the only activity to record a decrease in 2022. Growth of 1.8% in 2023 was the 3rd highest among these 10 activities. Overall, output was 9.0% higher in 2023 than it had been in 2005.

- Construction recorded the deepest and longest contraction following the global financial and economic crisis: its output fell 20.8% between 2007 and 2014, with output falling every year during this period. As such, the 2.0% increase recorded for construction in 2015 was the 1st annual growth in 8 years and was followed by growth between 1.0% and 2.5% through to 2019. In 2020, construction output fell for the 1st time since 2014, down 5.0%. This was followed by 3 years of diminishing growth: 3.1% in 2021, 1.4% 2022 and 0.9% in 2023. Despite the period of sustained growth between 2015 and 2019 and more recently between 2021 and 2023, construction output in 2023 remained 8.5% lower than it had been in 2005. This was the only overall fall among these 10 activities.

(2005 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_a10)

- Professional, scientific, technical, administrative and support services also reported only slightly interrupted growth between 2005 and 2019, with a fall of 6.4% in 2009 and almost no change (down 0.1%) in 2012. The fall in 2020 was somewhat smaller than in 2009, down 5.0%. The recovery from 2021 to 2023 (up 6.9%, 5.3% and 1.3%, respectively) left output in 2023 some 8.3% above its 2019 level. Looking over the whole period from 2005 to 2023, professional, scientific, technical, administrative and support services recorded an overall increase of 47.5%, the 2nd highest growth (after information and communication activities).

- Real estate activities didn’t post any negative rates of change between 2005 and 2019 but did record a fall in output (down 0.8%) in 2020. This was followed by a full recovery in 2021 and further growth in 2022 and 2023, with increases of 1.9%, 2.1% and 1.4%, respectively. Overall, real estate output was 28.0% higher in 2023 than in 2005, the 3rd highest increase among these activities.

- Financial and insurance activities recorded 4 years of falling output between 2005 and 2019, in 2009, 2012, 2014 and 2016. The 0.3% fall in 2020 was the smallest decrease among the 9 activities shown in Figures 4 and 5 which recorded falls that year. The 0.2% growth recorded in 2023 for financial and insurance activities was the 3rd lowest rate of change. Overall growth between 2005 and 2023 was 20.6%.

- Public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities reported almost uninterrupted growth between 2005 and 2019: in 2012, the level of value added was marginally lower than the year before (down 0.1%), while in 2013 it was the same as in 2012. As such, the fall of 2.6% in 2020 was the only clear downward movement observed for these activities during the period studied. The 2020 contraction was followed by a more than full recovery in 2021 as growth was 3.5%; this was followed by further growth of 1.7% in 2022 and 1.2% in 2023. An overall increase of 18.3% was recorded between 2005 and 2023.

- Arts, entertainment and other services recorded 4 years of falling output between 2005 and 2019 (in 2009, 2010, 2012 and 2013), as well as 1 year of no change (2016). In 2020, it recorded the largest fall among the 10 activities, down 17.4%. This fall reflected the major impact of the COVID-19 crisis on arts, entertainment and other services. There was growth in 2021, 2022 and 2023, at 4.3%, 11.6% and 4.0%, respectively, which left the level of output in 2023 approximately the same as it had been in 2019. As such, this was 1 of only 2 activities shown in Figures 4 and 5 which hadn’t, by 2023, surpassed its pre-crisis level of output, the other being agriculture, forestry and fishing. An overall increase of 12.1% was recorded between 2005 and 2023.

(2005 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_a10)

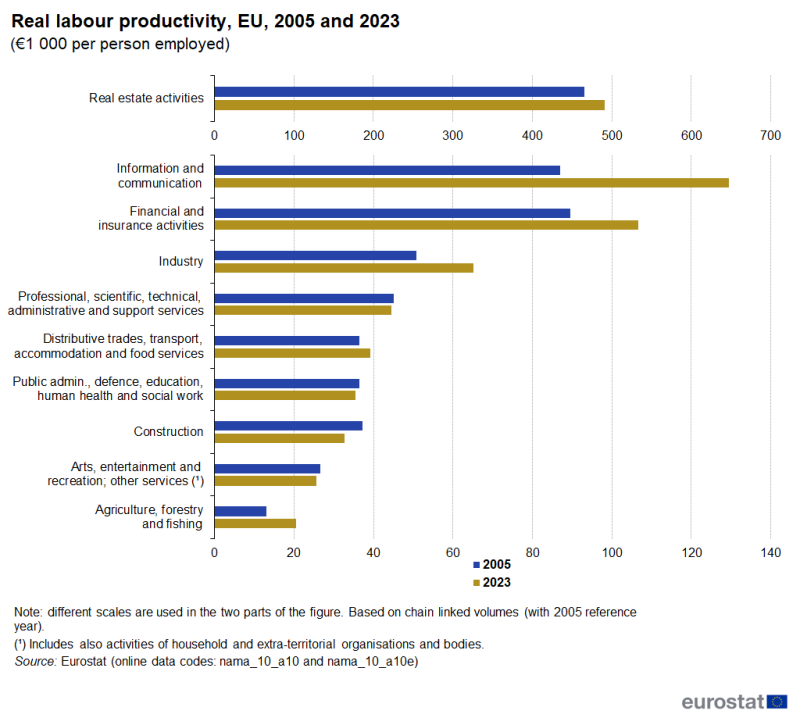

Labour productivity

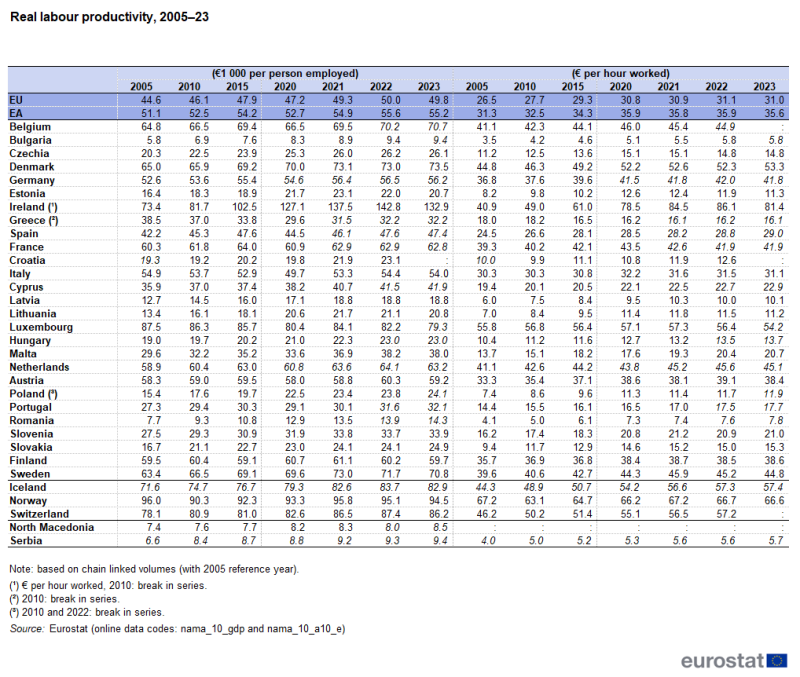

To eliminate the effects of inflation, labour productivity per person employed can be calculated using data adjusted for price changes. An analysis of labour productivity per person employed in real terms (based on chain linked volumes) over the 18-year period from 2005 to 2023 shows increases in the EU for 6 of the 10 economic activities covered. In relative terms, the largest productivity gains were recorded for agriculture, forestry and fishing (up 57.1%) and for information and communication activities (up 48.6%). Smaller increases were observed for industry, for financial and insurance activities, for distributive trades, transport, accommodation and food services, and for real estate activities – see Figure 6. Note that a precise comparison of labour productivity levels in real terms between activities can only be analysed for reference year 2005 due to the non-additivity of chain linked volumes.

(€1 000 per person employed)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_a10) and (nama_10_a10e)

Further data on the development of real labour productivity measured either per person employed or per hour worked are shown in Table 4. Labour productivity per person employed increased, in real terms, between 2005 and 2023 in most EU countries, with Greece, Luxembourg and Italy recording falls. In a similar manner and over the same period, labour productivity per hour worked also increased in nearly all EU countries, Greece and Luxembourg again being exceptions. Note that there is a break in series for Greece for both indicators. Leaving aside the EU countries with a break in series (Ireland, Greece and Poland), the largest percentage increases for both of these real labour productivity measures were recorded in Romania, while the next highest rates were recorded in Bulgaria, Lithuania, Slovakia and Latvia.

Consumption and investment

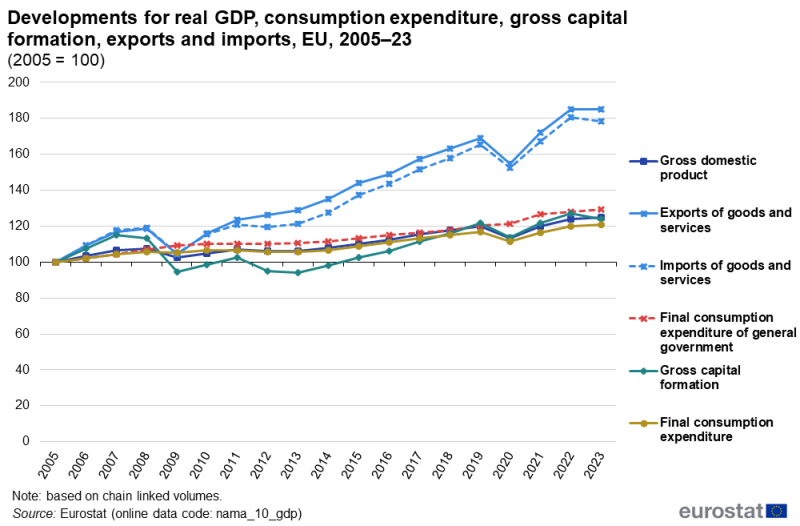

After falling 5.6% in 2020, the economic rebound observed in 2021 continued in 2022 and 2023: GDP increased in real terms by 6.0% in 2021, by 3.4% in 2022 and by 0.5% in 2023. As such, GDP in 2023 was 3.9% above its 2019 pre-COVID level. Figure 7 focuses the analysis on the development of the EU’s GDP components from the expenditure side.

- Final consumption expenditure rose overall by 20.8% in volume terms between 2005 and 2023 (see Figure 7), despite slight falls in 2009, 2012 and 2013, and a larger fall in 2020 (down 4.8%).

- Final consumption expenditure of general government rose notably faster than final consumption expenditure as a whole, up 29.5% between 2005 and 2023, despite slight falls in 2011 and 2012. Final consumption expenditure of general government increased 1.1% in 2020, the only expenditure item shown in Figure 7 to record an increase during the year that the COVID-19 crisis started.

- During the same period (2005–23), gross capital formation was relatively volatile: it increased between 2005 and 2007 by 14.9% and fell by a greater amount (17.7%) between 2007 and 2009 (during the global financial and economic crisis). It then increased by 8.3% between 2009 and 2011 and fell by 8.1% between 2011 and 2013. A subsequent period of regular growth resulted in an overall increase of 29.2% between 2013 and 2019. A fall of 6.6% was observed in 2020, a larger fall than for the final consumption expenditure items shown in Figure 7. Equally, the rebound in gross capital formation in 2021 and 2022 (up 7.2% and 4.4%, respectively) was larger than for final consumption expenditure. In 2023, gross capital formation fell 2.7%.

- The growth in exports of goods and services exceeded the growth in imports in 2008, between 2010 and 2013, and again in 2017, 2021 and 2023, whereas imports grew faster (or decreased less) in the other years since 2005. In 2020, the value of exports fell 8.5% compared with 2019, while imports fell 7.9%. In 2021 and 2022, the value of exports and of imports rebounded strongly while in 2023 the rates of change were much more moderate. Exports were 85.0% higher in 2023 than in 2005, whereas the equivalent increase for imports was 78.4%.

(2005 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp)

Having grown each year from 2005 to 2008, consumption expenditure by households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) in the EU fell 1.1% in 2009. Growth in 2010 (0.9%) and 2011 (0.3%) returned this expenditure to its 2008 level, before it fell again in 2012 (down 0.8%) and 2013 (down 0.6%). Thereafter, consumption expenditure by households and NPISHs increased during 6 consecutive years, accelerating from 1.1% growth in 2014 to 2.2% in 2016 and 2017, before slowing to 1.5% in 2019. In 2020, this sustained period of growth was reversed, as consumption expenditure by households and NPISHs fell 7.1%. This fall was recovered in 2021 and 2022 as growth rates of 4.6% and 4.1%, respectively, were recorded; growth continued in 2023 at a more moderate rate (up 0.4%).

In 2010, the rate of growth for EU general government expenditure decreased in volume terms and this rate of change remained relatively stable (within the range of -0.2% to 0.4%) between 2011 and 2013, before returning to somewhat stronger growth (between 1.0% and 2.0%) from 2014 to 2020. The increase in 2021 was above this range, at 4.1%, while in 2022 and 2023 increases of 1.3% and 1.1% were recorded.

Gross fixed capital formation (investment) in the EU experienced a sharp fall in 2009 (-11.3%) and smaller falls in 2008 (-0.3%) and 2010 (-0.5%). An increase of 2.1% in 2011 was followed by further falls in 2012 (-2.8%) and 2013 (-2.0%). However, increases in investment were observed in each of the next 6 years, rising in the range of 2.1% to 6.5% each year. As for most other expenditure indicators, this period of growth ended abruptly in 2020 when investment fell by 5.2%. The combined growth of 3.5% in 2021 and 2.5% in 2022 resulted in a recovery of what had been lost in 2020, while in 2023 further growth of 1.6% was recorded.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp)

In current price terms, consumption expenditure by households and non-profit institutions serving households contributed 52.3% of the EU’s GDP in 2023. The share of gross capital formation was 22.8% and that of general government expenditure was 21.1%. The external balance of goods and services had a share of 3.8% (see Figure 9).

(% share of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp)

Among the EU countries, there was a wide variation in investment intensity (see Figure 10). This may, in part, reflect different stages of economic development as well as growth dynamics over recent years, in particular the impact of the COVID-19 and cost-of-living crises. In 2023, gross fixed capital formation (in current prices) as a share of GDP was 22.2% in the EU and almost the same (22.1%) in the euro area. It was highest in Czechia (27.0%), Romania (26.9%), Estonia (26.6%) and Hungary (26.3%). The lowest share was in Greece (13.9%).

(% share of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp)

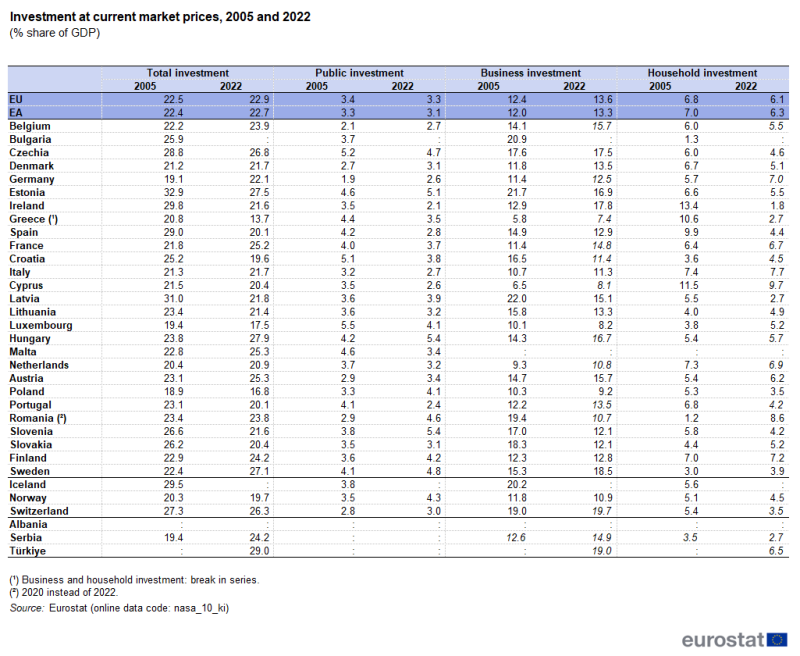

The vast majority of investment in the EU was made by the private sector, as can be seen from Table 5; note that the latest data are for 2022 and therefore these data reflect the continued rebound in investment (after the COVID-19 crisis).

In 2022, investment by businesses accounted for 13.6% of the EU’s GDP, whereas the equivalent figures for household and public sector investment were 6.1% and 3.3%, respectively.

Relative to GDP, Hungary (5.4%) had the highest ratio of public investment to GDP in 2022, while investment by the business sector was highest in Sweden (18.5%), and by households it was highest in Cyprus (9.7%). Investment by households (as a share of GDP) in 2022 was notably lower than in 2005 in Ireland, Greece and Spain, while it was notably higher in Romania (2020 compared with 2005); note that there is a break in series for Greece.

(% share of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (nasa_10_ki)

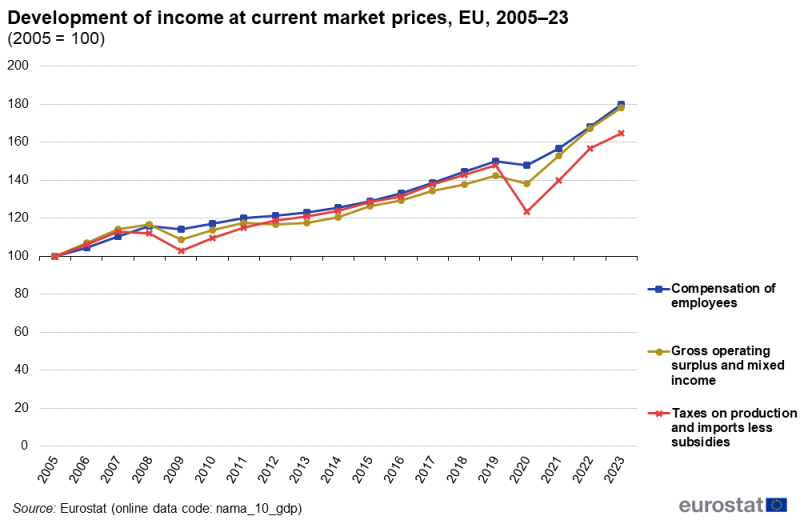

Income

An analysis of the EU’s GDP from the income side shows that the distribution between the production factors of income resulting from the production process was led by the compensation of employees (see Figure 11). This form of income accounted for 47.0% of GDP at current market prices in 2023 in the EU and 47.7% in the euro area. The shares for gross operating surplus and mixed income were 42.0% of GDP in the EU and 41.7% in the euro area. For taxes on production and imports less subsidies, the shares were 10.9% in the EU and 10.6% in the euro area.

Ireland had by far the lowest share of the compensation of employees in GDP (26.2%), followed by Greece (34.7%), while a peak share of 53.2% was recorded in Slovenia. The particularly low share in Ireland is a consequence of globalisation related effects.

(% share of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp)

By 2011, the income aggregates in the EU had recovered from the losses experienced during the global financial and economic crisis. Income from the compensation of employees increased every year from 2010 to 2019, gaining 31.2% overall (in current price terms) between 2009 and 2019. For gross operating surplus and mixed income, overall growth was almost the same (up 30.8% during the same 9-year period); this increase was composed of annual increases every year except for 2012. Income from taxes on production and imports increased each and every year from 2010 to 2019, resulting in overall growth of 43.9%.

The developments across the EU in 2020 (compared with 2019) were in stark contrast to the established series of increases prior to the COVID-19 crisis: the compensation of employees decreased 1.5%, gross operating surplus and mixed income decreased 3.1%, and income from taxes on production and imports decreased by as much as 16.4%. The subsequent rebound recorded in 2021 more than outweighed the decrease in 2020 for the compensation of employees and for gross operating surplus and mixed income; taxes on production and imports remained, in 2021, some 5.5% below their 2019 level. An increase of 12.4% in 2022 brought the level of taxes on production and imports well above the previous peak from 2019. The latest rates of change – for 2023 compared with 2022 – were 7.0% for the compensation of employees, 6.6% for gross operating surplus and mixed income, and 5.1% for taxes on production and imports.

(2005 = 100)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp)

Household consumption

Consumption expenditure of households accounted for at least half of GDP (at current market prices) in 2023 in 17 of the EU countries; this share was highest in Greece (66.9%). By contrast, it was lowest in Ireland (26.6%) and Luxembourg (29.9%). Despite the low share of consumption expenditure of households in GDP observed in Luxembourg, this was where the highest per inhabitant expenditure level was observed, even after adjusting for price level differences between EU countries (26 806 PPS per inhabitant) – see Table 6.

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp) and (nama_10_pc)

Aside from Luxembourg, average household consumption expenditure per inhabitant in PPS terms in 2023 was also relatively high in Austria (22 854 PPS) and Belgium (22 265 PPS). By contrast, average household consumption expenditure per inhabitant was 13 633 PPS in Hungary.

An analysis of real developments in average consumption expenditure per inhabitant in euro terms (based on a chain linked volume index) over the period 2019–23 shows that the fastest growth was recorded in Bulgaria, Croatia (2019–22) and Romania, where annual average increases were at least 3.4%. A total of 6 EU countries recorded a decrease in household consumption expenditure per inhabitant between these years, with the largest decrease in Czechia (down 2.0% per year on average).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The European system of national and regional accounts (ESA) provides the methodology for national accounts in the EU. The current version, ESA 2010, was adopted in May 2013 and has been implemented since September 2014. It is fully consistent with worldwide guidelines for national accounts, the 2008 SNA. Please note that most EU countries are carrying out benchmark revisions during 2024. For further details, please consult the Eurostat website.

GDP and main components

The main aggregates of national accounts are compiled from institutional units, namely non-financial or financial corporations, general government, households, and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH).

Data within the national accounts domain encompasses information on GDP components, employment, final consumption aggregates and savings. Many of these variables are calculated on an annual and on a quarterly basis.

GDP is the central measure of national accounts, which summarises the economic position of a country (or region). It can be calculated using different approaches: the output approach; the expenditure approach; and the income approach.

An analysis of GDP per inhabitant removes the influence of the absolute size of the population, making comparisons between different countries easier. GDP per inhabitant is a broad economic indicator of living standards.

GDP data in national currencies can be converted into purchasing power standards (PPS) using purchasing power parities (PPPs) that reflect the purchasing power of each currency, rather than using market exchange rates; in this way differences in price levels between countries are eliminated. The volume index of GDP per inhabitant in PPS is expressed in relation to the EU average (set to equal 100). If the index of a country is higher/lower than 100, that country’s level of GDP per head is above/below the EU average; this index is intended for cross-country comparisons rather than temporal comparisons.

The calculation of the annual rate of change of GDP using chain linked volume indices (real changes) is intended to enable comparisons of the dynamics of economic development both over time and between economies of different sizes, irrespective of price levels.

Complementary data

Economic output can also be analysed by activity. At the most aggregated level of analysis used for national accounts, 10 NACE headings are identified

- agriculture, forestry and fishing

- industry

- construction

- distributive trades, transport, accommodation and food services

- information and communication

- financial and insurance activities

- real estate activities

- professional, scientific, technical, administrative and support services

- public administration, defence, education, human health and social work

- arts, entertainment, recreation, other services and activities of household and extra-territorial organisations and bodies

An analysis of output by activity over time can be facilitated by using a volume measure (reflecting real changes), in other words, by deflating the value of output to remove the impact of price changes. Each activity is deflated individually to reflect the changes in the prices of its associated products.

A further set of national accounts data is used within the context of competitiveness analysis, such as labour productivity measures. Productivity measures expressed in PPS are particularly useful for cross-country comparisons. GDP per person employed is intended to give an overall impression of the productivity of national economies. It should be kept in mind, though, that this measure depends on the structure of total employment and may, for instance, be lowered by a shift from full-time to part-time work. GDP per hour worked gives a clearer picture of productivity as the incidence of part-time employment varies greatly between countries and activities.

Annual information on household expenditure is available from national accounts compiled through a macroeconomic approach. An alternative source for analysing household expenditure is the household budget survey (HBS): information for the latter is obtained by asking households to keep a diary of their purchases and is much more detailed in its coverage of goods and services as well as the types of socioeconomic analysis that are compiled and published. The HBS is only carried out every 5 years: at the time of writing (June 2023), data for the 2020 reference year are available for nearly all EU countries as well as an estimate for the EU.

Symbols

Note on tables

- italics are used to show where data are estimates or provisional

- a colon ‘:’ is used to show where data aren’t available

Context

European institutions, governments, central banks as well as other economic and social bodies in the public and private sectors need a set of comparable and reliable statistics on which to base their decisions. National accounts can be used for various types of analysis and evaluation. The use of internationally accepted concepts and definitions enables an analysis of different economies, such as the interdependencies between the economies of the EU countries, or a comparison between the EU and non-EU countries.

Business cycle and macroeconomic policy analysis

Among the main uses of national accounts data is the need to support European economic policy decisions and the achievement of economic and monetary union (EMU) objectives with high-quality short-term statistics that enable the monitoring of macroeconomic developments and the derivation of macroeconomic policy advice. For instance, 1 of the most basic and long-standing uses of national accounts is to quantify the rate of change of an economy, in simple terms the change in GDP. Core national accounts figures are used to develop and monitor macroeconomic policies, while detailed national accounts data can also be used to develop sectoral or industrial policies, particularly through an analysis of input-output tables.

Since the beginning of the EMU in 1999, the European Central Bank (ECB) has been 1 of the main users of national accounts. The ECB’s strategy for assessing the risks to price stability is based on 2 analytical perspectives, referred to as the ‘2 pillars’: economic analysis and monetary analysis. A large number of monetary and financial indicators are evaluated in relation to other relevant data that allow the combination of monetary, financial and economic analysis, for example, key national accounts aggregates. In this way, monetary and financial indicators can be analysed within the context of the rest of the economy.

The Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs monitors economic developments. The EU has a yearly cycle of economic policy coordination called the European Semester. Each year, the European Commission conducts a detailed analysis of EU countries’ plans for budgetary, macroeconomic and structural reforms and provides country-specific recommendations for the following 12 to 18 months.

The Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs also produces the European Commission’s macroeconomic forecasts 4 times a year (autumn, winter, spring and summer), in coordination with the annual cycle of the European Semester. These forecasts cover all EU countries in order to derive forecasts for the euro area and the EU; they often also include outlooks for candidate countries, as well as some other non-EU countries.

The analysis of public finances through national accounts is another well-established use of national accounts statistics. Within the EU, a specific application was developed in relation to the convergence criteria for EMU, 2 of which refer directly to public finances. These criteria have been defined in terms of national accounts figures, namely, government surplus/deficit and government debt relative to GDP; see the article on government finance statistics for more information.

Regional, structural and sectoral policies

As well as business cycle and macroeconomic policy analysis, there are other policy-related uses of the EU’s national and regional accounts data, notably concerning regional, structural and sectoral issues.

The allocation of expenditure for the structural funds is partly based on regional accounts. Furthermore, regional statistics are used for ex post assessment of the results of regional and cohesion policy.

An economy that works for people is 1 of 6 strategic priorities for the EU and the EU countries during the period 2019–24. In support of these strategic priorities, common policies are implemented across all sectors of the EU economy while the EU countries implement their own national structural reforms.

The European Commission conducts economic analysis contributing to the development of the common agricultural policy (CAP) by analysing the efficiency of its various support mechanisms and developing a long-term perspective. This includes research, analysis and impact assessments on topics related to agriculture and the rural economy in the EU and non-EU countries, in part using the economic accounts for agriculture.

Target setting, benchmarking and contributions

Policies within the EU are increasingly setting medium or long-term targets, whether binding or not. For some of these, the level of GDP is used as a benchmark denominator.

National accounts are also used to determine EU resources, with the basic rules laid down in a Council Decision. The overall amount of own resources needed to finance the EU budget is determined by total expenditure less other revenue, and the maximum size of the own resources are linked to the gross national income of the EU.

As well as being used to determine budgetary contributions within the EU, national accounts data are also used to determine contributions to other international organisations, such as the United Nations (UN). Contributions to the UN budget are based on gross national income along with a variety of adjustments and limits.

Analysts and forecasters

National accounts are also widely used by analysts and researchers to examine the economic situation and developments. Social partners, such as representatives of businesses (for example, trade associations) or representatives of workers (for example, trade unions), also have an interest in national accounts for the purpose of analysing developments that affect industrial relations. Among other uses, researchers and analysts use national accounts for business cycle analysis and analysing long-term economic cycles and relating these to economic, political or technological developments.

Notes

* This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

Direct access to

- European sector accounts (background article)

- European system of national and regional accounts – ESA 2010 (background article)

- Main users of national accounts (background article)

- Annual national accounts (t_nama10), see

- Main GDP aggregates (t_nama_10_ma)

- Auxiliary indicators (population, GDP per capita and productivity) (t_nama_10_aux)

- Basic breakdowns of main GDP aggregates and employment (by industry and by assets) (t_nama_10_bbr)

- Detailed breakdowns of main GDP aggregates (by industry and consumption purpose) (t_nama_10_dbr)

- Regional economic accounts - ESA 2010 (t_nama_10reg)

- Annual national accounts (nama10), see

- Main GDP aggregates (nama_10_ma)

- Auxiliary indicators (population, GDP per capita and productivity) (nama_10_aux)

- Basic breakdowns of main GDP aggregates and employment (by industry and by assets) (nama_10_bbr)

- Detailed breakdowns of main GDP aggregates (by industry and consumption purpose) (nama_10_dbr)

- Breakdowns of non-financial assets by type, industry and sector (nama_10_nfa)

- Regional economic accounts (nama_10reg)

- Quarterly national accounts (namq_10)

- Annual sector accounts (ESA 2010) (nasa_10)

- Purchasing power parities (prc_ppp)

ESMS metadata files

- National accounts (ESA 2010) (na10) (ESMS metadata file – na10_esms)

- Supply, use and Input–output tables (ESMS metadata file – naio_10_esms)

Methodology manuals

- Essential SNA – Building the basics – 2014 edition

- European system of accounts – ESA 2010

- European system of accounts – ESA 2010 – Transmission programme of data (multilingual)

- Eurostat–OECD Methodological Manual on Purchasing Power Parities

- Handbook on prices and volumes measures in national accounts

- Handbook on the compilation of statistics on illegal economic activities in national accounts and balance of payments

- Manual on the changes between ESA 95 and ESA 2010 – 2014 edition

- Practical guidelines for revising ESA 2010 data – 2019 edition

Other methodological information