Tourism industries - employment

Data extracted in April 2024.

Planned article update: May 2027.

Highlights

Persons employed in total tourism industries 2021 (%)

This article presents statistics on employment in the tourism industries in the European Union (EU). Tourism statistics focus on either the accommodation sector (data collected from hotels, campsites, etc.) or on tourism demand (data collected from households), and relate mainly to physical flows (arrivals or nights spent in tourist accommodation or trips made by a country’s residents). However, this analysis of employment in tourism is based on data from other areas of official statistics, in particular structural business statistics (SBS), the labour force survey (LFS) and the labour cost survey (LCS).

This article analyses the tourism sector with a focus on its contribution to the labour market in the EU and its potential to create jobs for economically less advantaged socio-demographic groups or regions.

Full article

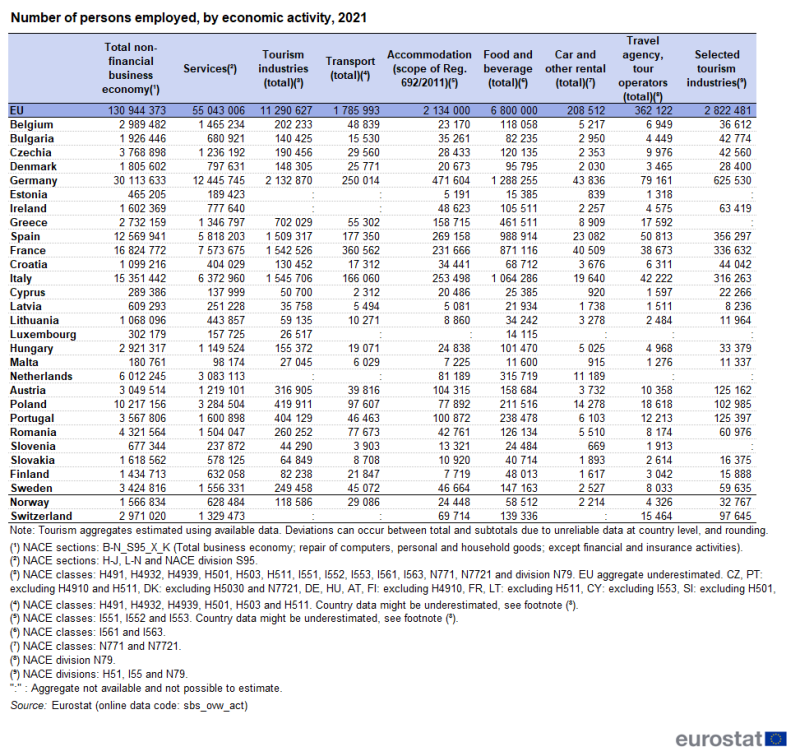

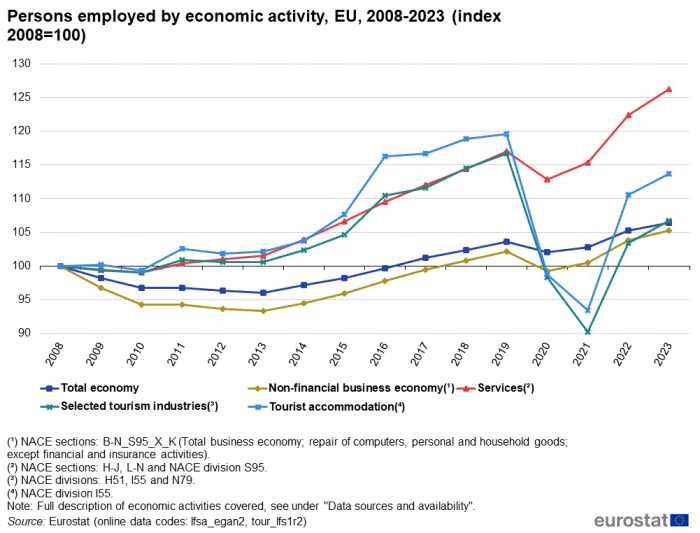

In 2021, the tourism industries employed over 11.2 million people in the EU

Economic activities related to tourism (but not necessarily relying only on tourism — see the section "Data sources" for further details) employed over 11.2 million people in the European Union (see Table 1). 6.8 million of these people worked in the food and beverage industry, while 1.8 million were employed in passenger transport. The accommodation sector (not including real estate) accounted for more than 2.1 million jobs in the EU; travel agencies and tour operators accounted for 0.4 million. The three industries that rely almost entirely on tourism (accommodation, travel agencies/tour operators, air transport) employed over 2.8 million people in the EU. These three industries will hereafter be referred to as the "selected tourism industries".

In 2021 the tourism industries accounted for more than 20 % of people employed in the services sector. When looking at the total non-financial business economy, the tourism industries accounted for nearly 9 % of people employed. Among the EU countries, Greece recorded the highest share (25.7 % or more than one in four people employed) followed by Cyprus and Malta with respectively 17.5 % and 15.0 % (see Figure 1).

In absolute terms, Germany had the highest employment in the tourism industries (2.1 million people, not including passenger rail transport interurban), followed by Italy, France (not including passenger air transport) and Spain (1.5 million each). These four countries accounted for over half (60 %) of employment in the tourism industries across the EU.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_ovw_act)

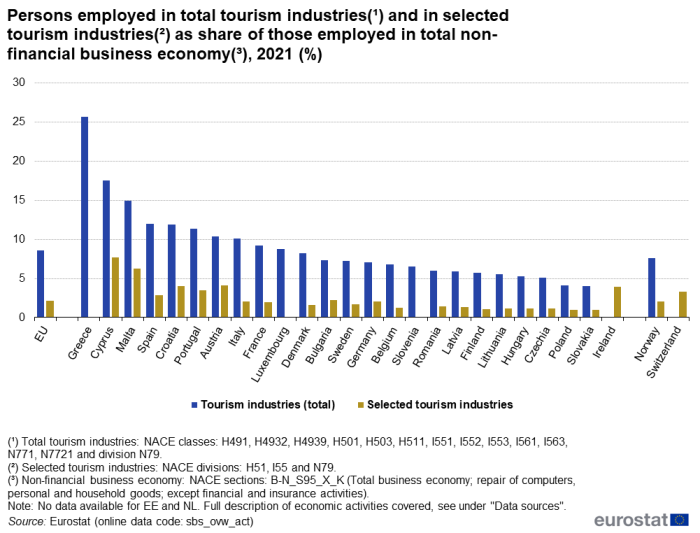

In 2021, over one out of four (29 %) people employed in the selected tourism industries, worked in micro-enterprises that employ fewer than 10 people. This share is one percentage point lower than the 30 % observed for the total non-financial business economy (see Figure 2). Looking at the three selected tourism industries separately, 44 % of employment in travel agencies and tour operators was in micro-enterprises, while for the accommodation sector this figure was 30 %. Not surprisingly, small and medium-sized enterprises (< 250 staff) are of minor importance in air transport, with 88 % of people employed in the sector working in companies employing 250 people or more.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_ovw)

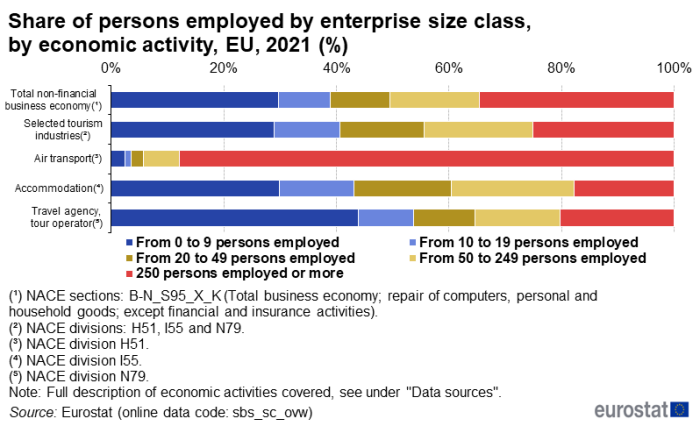

Looking at the longer term evolution of the tourism labour market, the economic crisis of 2008 led to a fall in total employment which started recovering in 2014 and reached the pre-crisis levels in 2016 (see Figure 3). However, this was not the case for the services sector, including the selected core tourism industries, which during the period 2008-2016 has had an average annual growth rate of +2.4 %. More specifically, during this period, the selected tourism industries registered an average annual growth of +2.0 %, while the average growth for the tourist accommodation sector was +3.8 %. This shows the tourism industry’s potential as a growth sector, even in times of economic turmoil that significantly affect other sectors of the economy.

The positive trend in employment in the selected core tourism industries continued until 2019 when the number of people employed in the sector reached +17 % compared with 2008.

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic slowed economic activity and, as a result, the labour market. It clearly had a negative impact on employment in tourism, as this was one of the most affected sectors due to the resulting travel restrictions, health protocols and the drop in demand among tourists. Tourism was one of the most affected sectors due to the resulting travel restrictions, health protocols and the drop in demand among tourists. This was reflected in the employment in the selected tourism industries, with a sharp drop by -16 % in 2020 compared with 2019. This drop was significantly higher than the -3 % and -4 % observed for the non-financial business economy and the services sector respectively. Even though the non-financial business economy and the services sector started recovering already in 2021, for the selected tourism industries only the year 2022 showed signs of recovery, and the positive trend continued also in 2023. However, the selected tourism industries have not reached yet the pre-pandemic levels of 2019, while the non-financial business economy and the services sectors surpassed them in 2023.

(index 2008=100)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan2), (tour_lfs1r2)

Characteristics of jobs in tourism industries

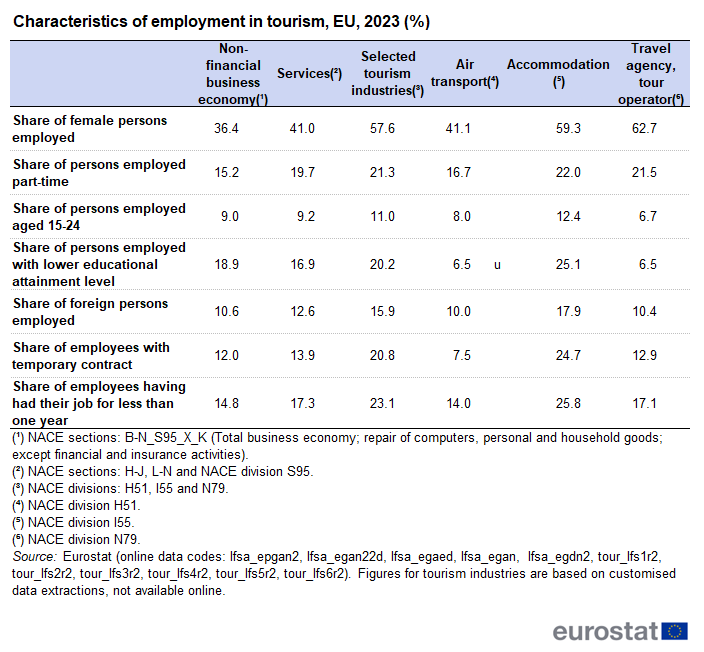

Table 2 shows the main characteristics of jobs in the tourism industries, and compares tourism with the entire services sector and the entire non-financial business economy. This table is discussed in more detail further in this article.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_epgan2), (lfsa_egan22d), (lfsa_egaed), (lfsa_egan), (lfsa_egdn2), (tour_lfs1r2), (tour_lfs2r2), (tour_lfs3r2), (tour_lfs4r2), (tour_lfs5r2), (tour_lfs6r2). Figures for tourism industries are based on customised data extractions, not available online

Tourism creates jobs for women

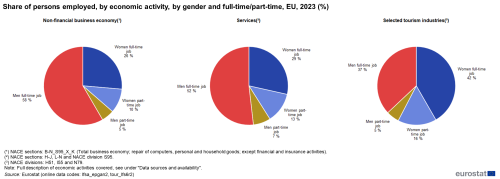

The tourism industry is a major employer of women (see Table 2, Figure 4 and Table 2A in the excel file). In 2023, compared with the total non-financial business economy where 36 % of people employed were female, the labour force of the tourism industries included more female workers (58 %) than male workers. The highest proportions were seen in travel agencies and tour operators (63 %), followed by the accommodation sector (59 %). Even though over one out of four women working in the tourism industries worked part-time (compared with just over one in eight men), women working full-time still represented the biggest share of employment (42 %, see Figure 4). Female employment accounted for less than half of tourism industry employment in only three countries (Luxembourg, Malta and Cyprus); for the accommodation sector this was the case only for Malta and Cyprus. In Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania, more than two out of three people employed in tourism were women.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_epgan2), (tour_lfs6r2)

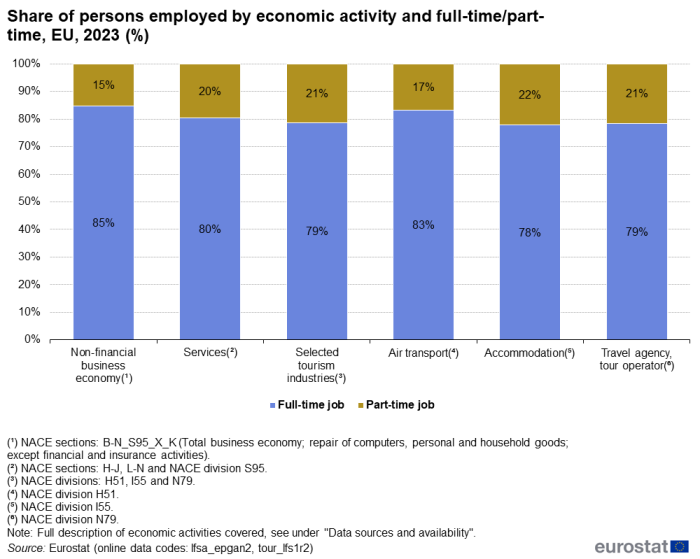

Part-time employment higher in the tourism industries

In 2023, the proportion of part-time employment in the tourism industries (21 %) was significantly higher than in the total non-financial business economy (15 %) and was comparable to the figure for the services sector as a whole (20 %) (see Table 2, Figures 4 and 5, and Table 2B in the excel file). Within the three selected tourism industries, the proportion of part-time employment in the accommodation sector was 22 %, while in travel agencies and tour operators was 21 %, and in air transport 17 % of staff worked on a part-time basis. In most countries for which data is available, the tourism industries had a higher proportion of part-time employment than the rest of the economy. This was not the case for the popular tourism destinations of Greece, Spain, Cyprus and Malta, where the proportion of part-time work in the tourism industries was lower than in the rest of the economy. In Croatia, Poland and Sweden, the proportion of part-time workers in tourism was more than double compared to the economy as a whole.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_epgan2), (tour_lfs1r2)

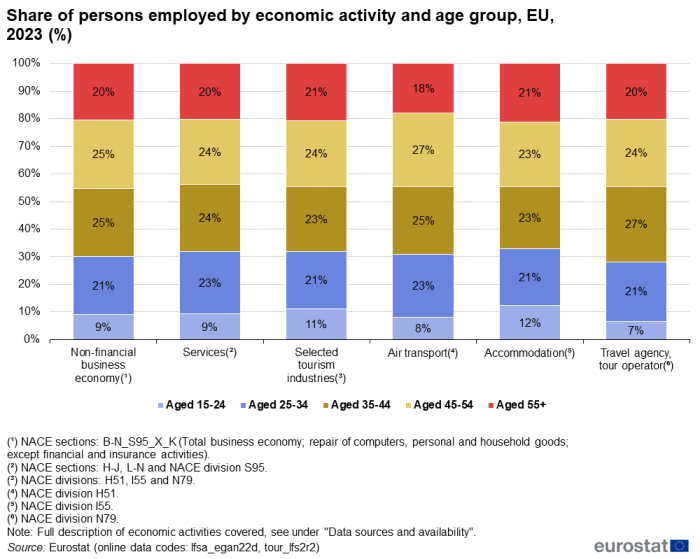

Tourism attracts a young labour force

Traditionally, the tourism industries have a particularly young labour force, as these industries can make it easy to enter the job market.

The share of young workers in the selected tourism industries remained high in 2023, with more than one in ten people (11 %) aged 15 to 24, while only 9 % of the labour force in the non-financial business economy were young workers. In the big majority of EU countries with available data, the share of young workers in tourism industries was above the proportion seen in the economy as a whole. The highest proportions of employed people aged 15 to 24 were registered in Denmark (28 %), Ireland and the Netherlands (both at 27 %) and Sweden (23 %) (see Table 2 and Table 2C in the excel file). In the subsector of accommodation, 12 % of the people employed were between 15 and 24 years old (see Figure 6), while in the four above mentioned countries, at least 29 % of persons employed in this sector were aged 15 to 24.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan22d), (tour_lfs2r2)

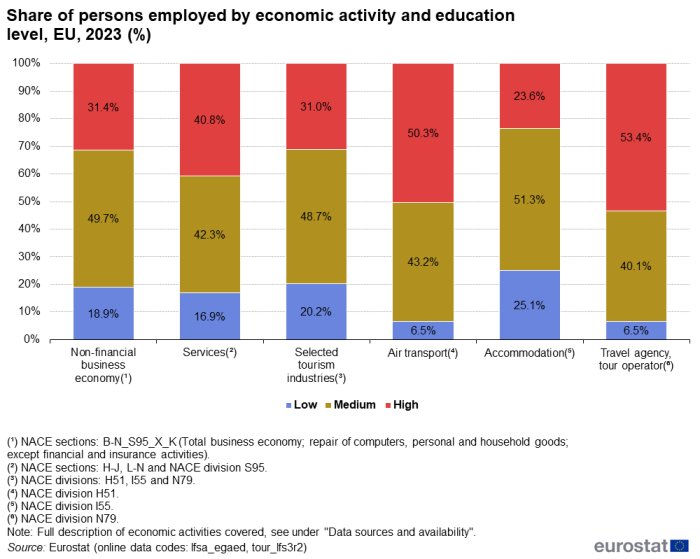

The tourist accommodation sector gives more opportunities to lower educated workers

The previous sections showed that tourism employs more female workers and young workers. In 2023, people with a lower educational level (those who have not finished upper secondary schooling) were more or less equally represented on the labour market as a whole and in the tourism sector (respectively 19 % and 20 %) — see Table 2, Figure 7 and Table 2D in the excel file. However, in the subsector of accommodation, 25 % of people employed had a lower educational level. In Spain, Luxembourg, Malta and Portugal at least one out of three people employed in tourist accommodation belong to this group. However, in Spain, Malta and Portugal, lower educated people are more represented in the whole labour force compared with the rest of EU countries.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egaed), (tour_lfs3r2)

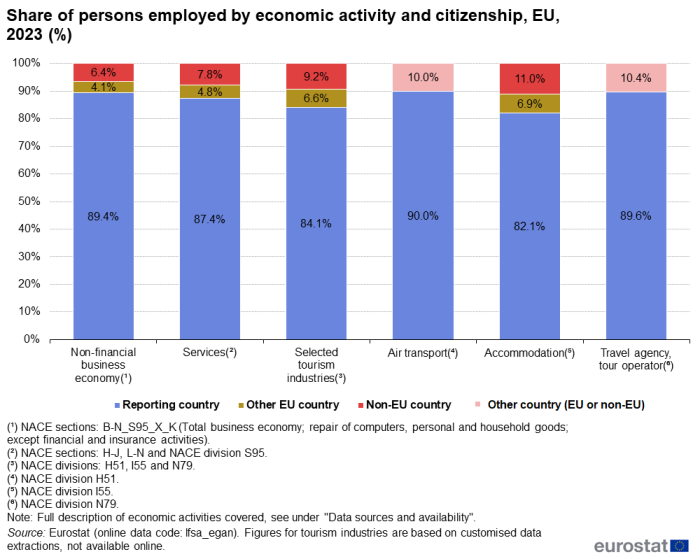

Nearly one in six people employed in tourism are foreign citizens

Many foreign citizens work in tourism-related industries (see Table 2, Figure 8 and Table 2E in the excel file). In 2023, they accounted for 16 % of the labour force in tourism industries (of which 7 % were from other EU countries and 9 % were from non-EU countries). In the services sector as a whole, the proportion of foreign citizens employed was 13 %, and in the total non-financial business economy it was 11 %. Looking at this in more detail, we see that foreign workers made up 10 % of the workforce in air transport and in travel agencies or tour operators, but 18% of the workforce in accommodation (i.e. more than one in six people employed in this sub-sector was a foreign citizen).

In three EU countries, more than two in five people employed in the selected tourism industries were foreign citizens: Cyprus (43 %), Luxembourg (64 %) and Malta (55 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan). Figures for tourism industries are based on customised data extractions, not available online

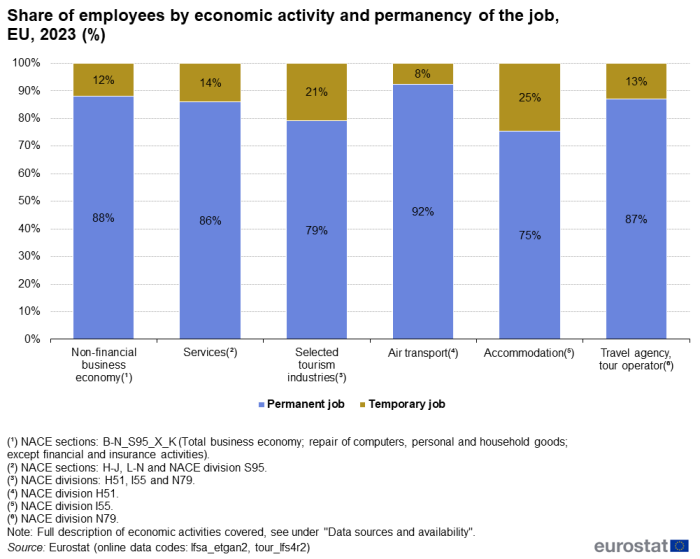

Jobs are less stable in tourism than in the rest of the economy

Since tourism tends to attract a young labour force, often at the start of their professional life (see above, Table 2 and Figure 6), certain key characteristics of employment in this sector are slightly less advantageous than in other sectors of the economy. The likelihood of occupying a temporary job was significantly higher in tourism than in the total non-financial business economy (21% versus 12 % of people employed) – see Table 2, Figure 9 and Table 2F in the excel file. There are big differences across the European Union, ranging from 5 % of temporary contracts in tourism in Hungary to more than 40 % in Greece, Italy and the Netherlands. In all countries fewer people have a permanent job in tourism than in the economy on average. In Bulgaria, Greece and Cyprus, the proportion of temporary workers was three to four times higher in tourism than in the non-financial business economy as a whole. In the accommodation sector, one in four people employed did not have a permanent contract.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_etgan2), (tour_lfs4r2)

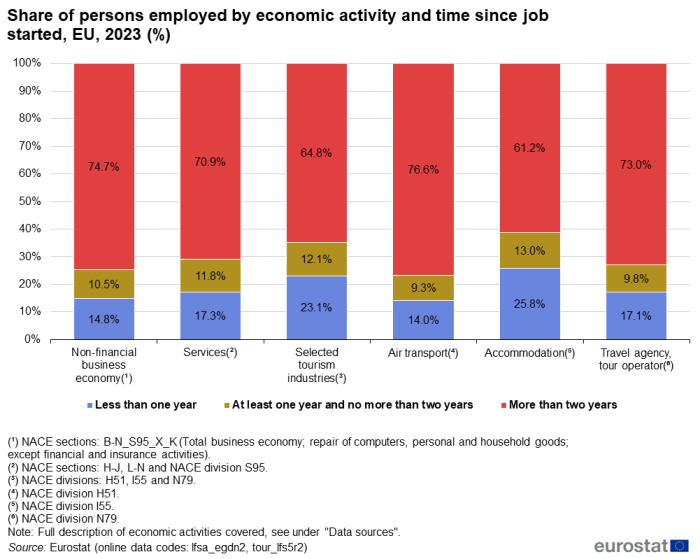

Similarly, the likelihood of an employee holding their current job for less than one year (see Table 2, Figure 10 and Table 2G in the excel file) was also higher in tourism than in the non-financial business economy as a whole (23 % versus 15 %). In the economy on average, three out of four employees (75 %) had worked with the same employer for two years or more, while in tourism this is the case for 65 % of people employed. Air transport tends to offer more stable jobs, with 14 % of employees having job seniority of less than one year, compared with 26 % in accommodation and 17 % for people employed by travel agencies or tour operators. More than 45 % of the workforce in the accommodation sector had held their job for less than one year in Greece and Cyprus.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egdn2), (tour_lfs5r2)

Seasonality and regional issues in tourism activities

High seasonality in tourism activities is only partly reflected in tourism employment

Tourism demand varies strongly in the course of the year (see article on ‘Seasonality in tourism demand’). Tourist accommodation has the highest occupancy rate in the summer months (see article on ‘Seasonality in the tourist accommodation sector’).

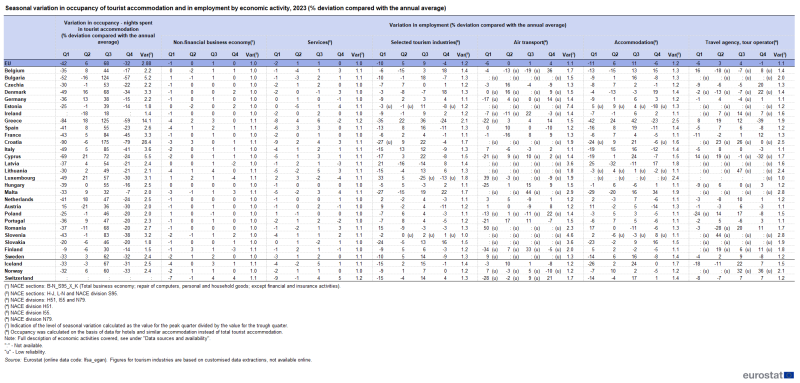

Table 3 shows that, in the EU on average, the number of nights spent in tourist accommodation is nearly three times higher in the third quarter of the year (the peak quarter) than in the first quarter (the lowest quarter). The peak quarter records more than double the number of nights than the lowest quarter in all but four countries (Estonia, Ireland, Slovakia and Finland). In Croatia, over 28 times more nights are spent in tourist accommodation between July and September than in the first three months of the year.

(% deviation compared with the annual average)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan). Figures for tourism industries are based on customised data extractions, not available online

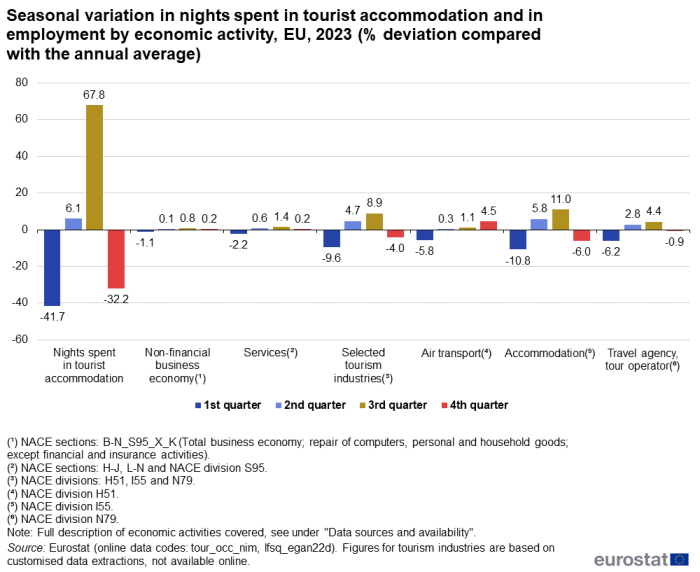

These seasonal fluctuations in tourist accommodation are only partly translated into seasonal fluctuations in employment. Employment in tourism in the peak quarter is only 1.2 times higher than in the lowest quarter (see Table 3 and Figure 11). The accommodation sector is the most affected by seasonality (peak quarter employment is 24.5 % higher than the lowest quarter), then travel agencies and tour operators (11.3 % higher) and air transport (7.3 % higher).

(% deviation compared with the annual average)

Source: Eurostat (tour_occ_nim), (lfsq_egan22d). Figures for tourism industries are based on customised data extractions, not available online

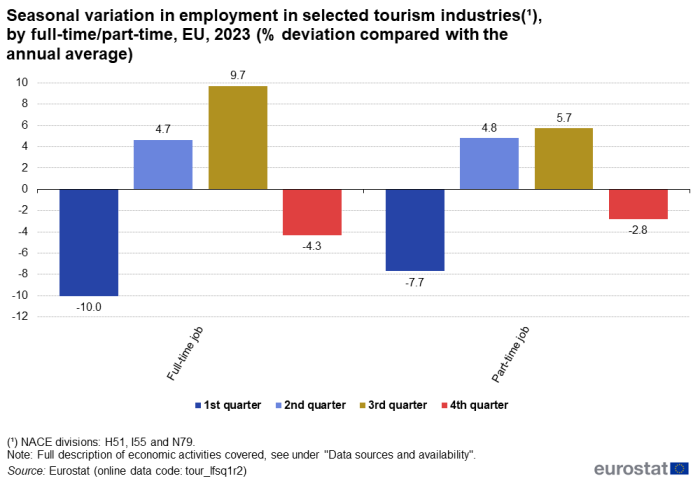

Figure 12 shows the different seasonal patterns for full-time and part-time jobs. The second quarter of the year seems to have a similar impact on both types of employment, while throughout the rest of the year the impact of seasonality is more important for full-time jobs.

(% deviation compared with the annual average)

Source: Eurostat (tour_lfsq1r2). Figures for tourism industries are based on customised data extractions, not available online

Regions with high tourist activity tend to have lower unemployment rates

Tourist activity can have a negative impact on the quality of life of the local population in popular tourist areas. However, the influx of tourists can also boost the local economy and labour market.

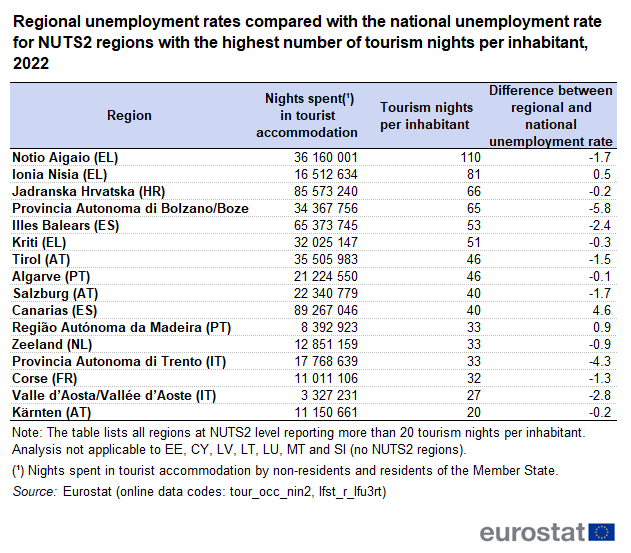

Comparing regional data on tourism intensity (e.g. the annual number of nights spent by tourists per capita of local population) with regional unemployment rates or their deviation from the national average unemployment rate, we see that in 2022, 21 of the 28 regions with the highest tourism intensity had an unemployment rate below the national average.

Table 4 lists the regions with a tourism intensity over 20 (tourism nights per local inhabitant). In all but three of these 20 regions, the unemployment rate lied below the national average. Two of the three regions where this did not hold true, the Canary Islands and Madeira, are island regions relatively remote from the mainland (and the mainland’s economy).

Source: Eurostat (tour_occ_nin2), (lfst_r_lfu3rt)

Wages and salaries and labour costs in the tourism industries

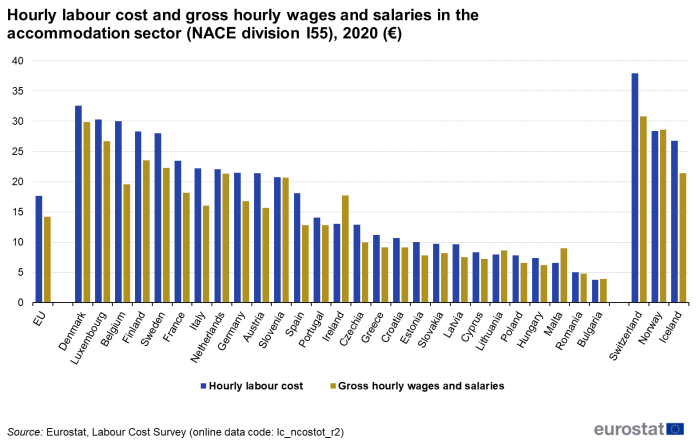

Hourly wages and salaries and labour costs in the accommodation sub-sector are below the average for the economy as a whole

Besides employment rates, another important feature of labour market analysis concerns labour costs for employers and wages and salaries for employees. This section takes a look at hourly labour costs and hourly wages and salaries, both in the economy as a whole and in the selected tourism industries. The data comes from a four-yearly survey, the most recent available reference year at the time of writing, was 2020.

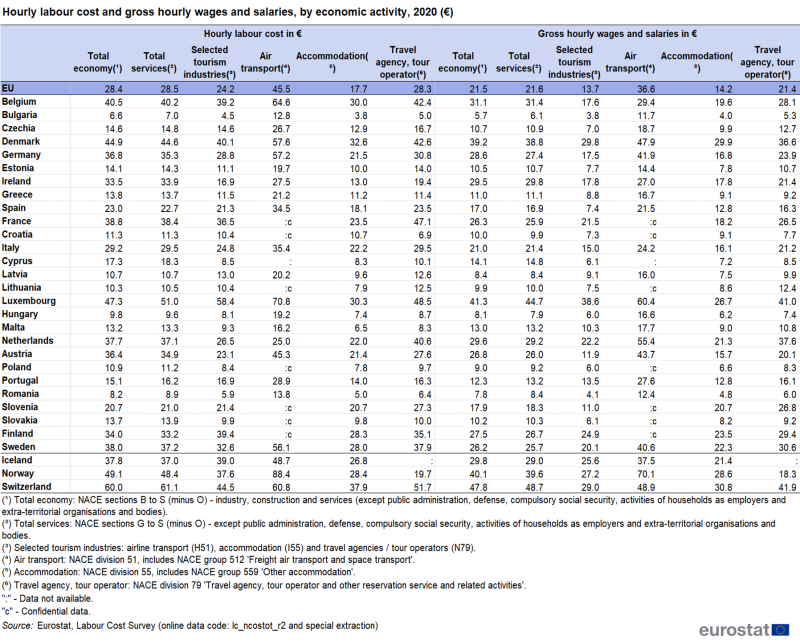

In the EU as a whole, labour costs and wages and salaries tend to be significantly lower in the tourism industries than they are in the total economy. In the economy, in 2020 the average hourly labour cost was €28.4 and average hourly wages and salaries were €21.5. In the three selected tourism industries (air transport, accommodation, travel agencies & tour operators) in the same year, the average hourly labour cost was €24.2 and the average gross hourly wages and salaries amounted to €13.7 (see Table 5 and Figure 13).

(€)

Source: Eurostat, Labour Cost Survey (lc_ncostot_r2) and special extraction

(€)

Source: Eurostat, Labour Cost Survey (lc_ncostot_r2) and special extraction

Given the characteristics of tourism jobs outlined above, this observation does not come as a surprise: a relatively young labour force (see Figure 6) with a higher proportion of temporary contracts (see Figure 9) and lower job seniority (see Figure 10) has a comparative disadvantage on the labour market, which leads to lower labour costs and wages and salaries. For the accommodation sector — which employs more people with a lower educational level and more part-timers — the differences are even higher. In 2020, for people employed in the accommodation sub-sector, gross hourly wages and salaries were €14.2. For air transport, they were €36.6 (well above the average for the economy as a whole), and for travel agencies and tour operators they were €21.4.

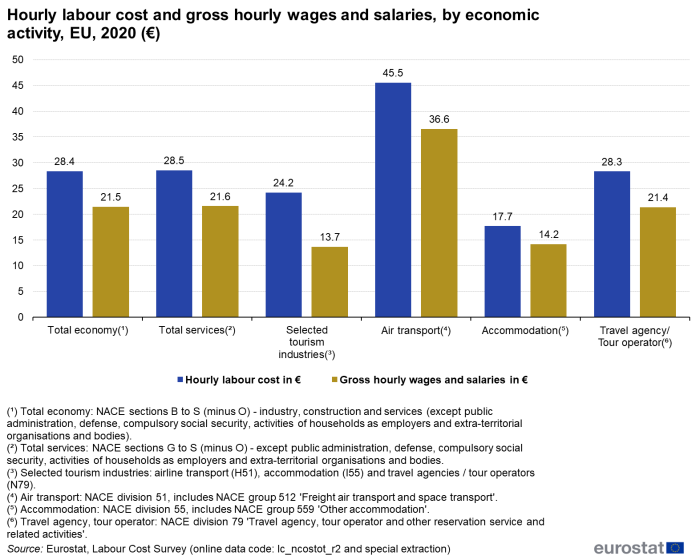

Gross hourly wages and salaries in tourism were highest in Luxembourg, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, France and Sweden, but these countries were also among the top ten countries with highest average hourly wages and salaries in the total economy (see Table 5 and Figure 14).

(€)

Source: Eurostat, Labour Cost Survey (lc_ncostot_r2) and special extraction

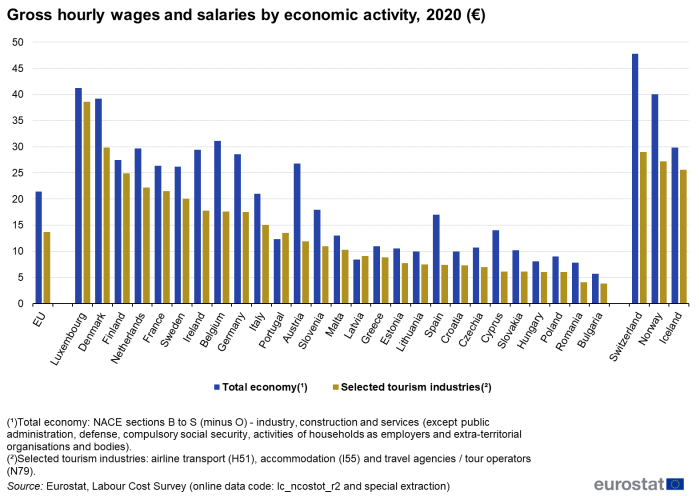

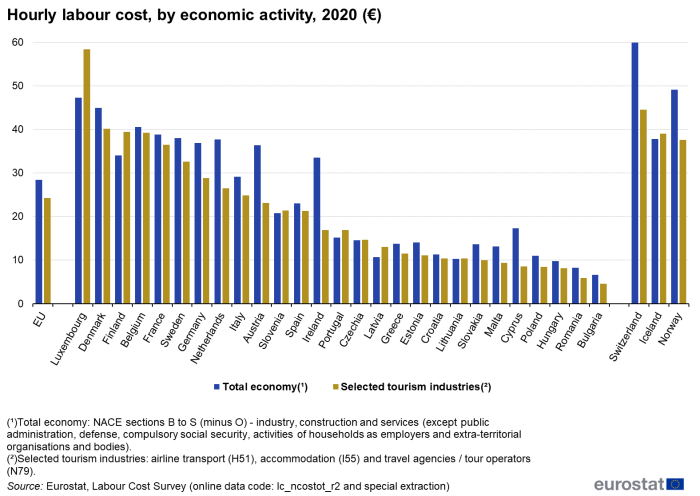

In 2020 only seven EU countries had higher hourly labour costs in tourism than the total economy: Czechia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia and Finland (see Table 5 and Figure 15); for gross hourly wages and salaries, this was the case only for Latvia and Portugal. Comparing the accommodation subsector with the economy as a whole, both hourly average labour costs and wages and salaries were lower for those employed in accommodation, and this was true across the EU, except the gross hourly wages and salaries for Portugal and the hourly average labour costs and gross hourly wages and salaries for Slovenia (see Table 5 and Figure 16). In normal conditions, the labour cost is expected to be higher than the wages and salaries, as labour cost also comprises the employer’s social contributions and net taxes minus subsidies. However, in 2020 many countries supported the (food and) accommodation sector with subsidies to stabilise employment, in some countries the subsidies exceeded in that year the total amount of labour taxes and social contributions, leading to a higher level of gross hourly wages and salaries compared with the hourly labour cost in Ireland and Malta.

(€)

Source: Eurostat, Labour Cost Survey (lc_ncostot_r2) and special extraction

(€)

Source: Eurostat, Labour Cost Survey (lc_ncostot_r2)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

This article includes data from three different sources:

This data is available at a detailed level of economic activity, which makes it possible to identify and select industries that are part of the tourism sector.

For Eurostat, tourism industries (total) include the following NACE Rev.2 classes:

- H4910 — Passenger rail transport, interurban

- H4932 — Taxi operation

- H4939 — Other passenger land transport n.e.c

- H5010 — Sea and coastal passenger water transport

- H5030 — Inland passenger water transport

- H5110 — Passenger air transport

- I5510 — Hotels and similar accommodation

- I5520 — Holiday and other short-stay accommodation

- I5530 — Camping grounds, recreational vehicle parks and trailer parks

- I5610 — Restaurants and mobile food service activities

- I5630 — Beverage serving activities

- N7710 — Renting and leasing of motor vehicles

- N7721 — Renting and leasing of recreational and sports goods

- NACE division N79 — Travel agency, tour operator reservation service and related activities.

However, many of these activities provide services to both tourists and non-tourists – typical examples include restaurants catering to tourists but also to locals and rail transport being used by tourists as well as by commuters. For this reason, this publication focuses on the following selected tourism industries which rely almost entirely on tourism:

- H51 — Air transport (including H512 ‘Freight air transport’).

- I55 — Accommodation (including I559 ‘Other accommodation’).

- N79 — Travel agency, tour operator reservation service and related activities (including N799 ‘Other reservation service and related activities’).

Context

The EU is a major tourist destination, with four countries among the world’s top ten destinations for holidaymakers, according to UNWTO[1] data. Tourism has the potential to contribute towards employment and economic growth, as well as to development in rural, peripheral or less-developed areas. These characteristics drive the demand for reliable and harmonised statistics within this field, as well as within the wider context of regional policy and sustainable development policy areas.

Tourism can play a significant role in the development of European regions. Infrastructure created for tourism purposes contributes to local development, while jobs that are created or maintained can help counteract industrial or rural decline. Sustainable tourism involves the preservation and enhancement of cultural and natural heritage, ranging from the arts to local gastronomy or the preservation of biodiversity.

In 2006, the European Commission adopted a Communication titled "A renewed EU tourism policy: towards a stronger partnership for European tourism" (COM(2006) 134 final). It addressed a range of challenges that will shape tourism in the coming years, including Europe’s ageing population, growing external competition, consumer demand for more specialised tourism, and the need to develop more sustainable and environmentally-friendly tourism practices. It argued that more competitive tourism supply and sustainable destinations would help raise tourist satisfaction and secure Europe’s position as the world’s leading tourist destination. It was followed in October 2007 by another Communication, titled "Agenda for a sustainable and competitive European tourism" (COM(2007) 621 final), which proposed actions in relation to the sustainable management of destinations, the integration of sustainability concerns by businesses, and the awareness of sustainability issues among tourists.

The Lisbon Treaty acknowledged the importance of tourism — outlining a specific competence for the EU in this field and allowing for decisions to be taken by a qualified majority. An article within the Treaty specifies that the EU "shall complement the action of the countries in the tourism sector, in particular by promoting the competitiveness of Union undertakings in that sector". "Europe, the world’s No 1 tourist destination — a new political framework for tourism in Europe" (COM(2010) 352 final) was adopted by the European Commission in June 2010. This Communication seeks to encourage a coordinated approach for initiatives linked to tourism and defined a new framework for actions to increase the competitiveness of tourism and its capacity for sustainable growth. It proposed a number of European or multinational initiatives — including a consolidation of the socioeconomic knowledge base for tourism — aimed at achieving these objectives.

Direct access to

- LFS series – Detailed annual survey results (t_lfsa)

- LFS series – Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- LFS series – Detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998 onwards) (lfsq)

- Enterprise by detailed NACE Rev.2 activity and special aggregates (sbs_ovw_act)

- Enterprise statistics by size class and NACE Rev.2 activity (from 2021 onwards) (sbs_sc_ovw)

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998) (ESMS metadata file — lfsq_esms)

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1051/2011 of 20 October 2011 implementing Regulation (EU) No 692/2011 concerning European statistics on tourism, as regards the structure of the quality reports and the transmission of the data.

- Regulation (EU) No 692/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2011 concerning European statistics on tourism and repealing Council Directive 95/57/EC.

- Summaries of EU Legislation: Tourism statistics

- Regional Statistics Illustrated - select statistical domain Tourism, Labour market.