Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Data extracted in April 2025.

Planned article update: June 2026.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2025 edition’. This report is the ninth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 13 seeks to achieve a climate-neutral world by mid-century and to limit global warming to well below 2° C — with an aim of 1.5° C — compared with pre-industrial times. It aims to strengthen countries’ climate resilience and adaptive capacity, with a special focus on supporting least-developed countries.

Climate action in the EU: overview and key trends

Climate change increases global air and ocean temperatures, impacts precipitation patterns, raises the global average sea level, provokes extreme weather events, harms biodiversity and increases ocean acidity. Its impacts threaten the viability of social, environmental and economic systems and may make some regions less habitable. Monitoring SDG 13 in an EU context focuses on climate change mitigation, climate change impacts and financing climate action. As surface temperatures rise, the EU continues to face intensifying climate impacts and economic losses from climate-related events. The EU’s net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions fell strongly in 2023, but more efforts are needed to meet the target of reducing net GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared with 1990. The 2030 target includes net GHG removals from land use, land use change and forestry, which have further declined since 2018 and remain far below the levels needed. The share of renewables has been rising steadily in the EU, but stronger progress will be needed to meet the new 2030 target. Financing of the transition saw new funds made available via the issuance of green bonds from corporate and governmental issuers. Climate finance has continued to progress, with climate-related expenditure for developing countries increasing further.

Climate change mitigation

Climate change mitigation aims to reduce emissions of climate-harming greenhouse gases (GHG) originating from human activity through measures such as promoting low-carbon technologies and practices or encouraging sustainable forest management and land use that enhance carbon removals. The EU has set into law the target to reach climate neutrality with no net GHG emissions by 2050. This means reducing GHG emissions as much as possible while compensating for the residual and unavoidable emissions by removing carbon dioxide (CO2), for example through natural carbon sinks and by using carbon-removal technologies. As an intermediate target on the path to climate neutrality in 2050, the EU has committed itself to reducing net GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels. In February 2024, the European Commission issued a Communication on the EU’s 2040 climate target, with a recommendation for a net reduction of emissions of 90% relative to 1990 levels, launching a debate with stakeholders.

GHG emissions fell strongly in 2023, but further progress is required to meet the 2030 target

Between 1990 and 2023, the EU achieved a 35.5% reduction in its net GHG emissions [1]. A large proportion of this reduction occurred between 2008 and 2023, with net emissions falling by 27.6% during this period. The decrease in emissions has further accelerated in recent years, with a particularly strong drop of 8.5% in 2023. However, over the next seven years emissions will need to fall even faster than they have on average over the past five years for the EU to reach its net GHG emission reduction target of 55% by 2030.

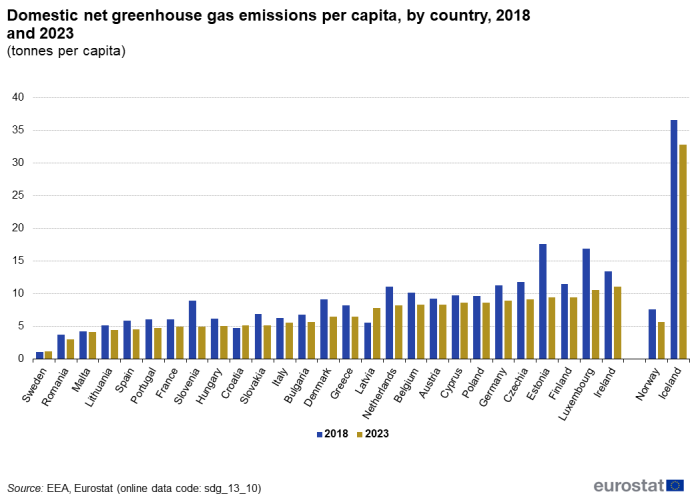

Per capita GHG emissions have fallen strongly in most Member States

In 2023, the EU’s net GHG emissions amounted to 6.8 tonnes of CO2-equivalent per capita, which is 18.1% lower than in 2018. Across Member States, domestic net GHG emissions [2] ranged from 1.2 tonnes per capita in Sweden to 11.1 tonnes in Ireland in 2023. Between 2018 and 2023, domestic net GHG emissions per capita fell in all but three Member States. The strongest reductions over the period from 2018 to 2023 were reported by Estonia, Slovenia and Luxembourg, where domestic per capita emissions fell by 46.0%, 43.8% and 37.3%, respectively. In contrast, domestic per capita emissions increased in Latvia, Sweden and Croatia, by 39.3%, 9.1% and 8.3%, respectively. The strong increase for Latvia is largely due to growing emissions from land use and forestry.

Carbon removals have declined and remain far from the target

Net GHG removals come from land use and forestry, which is also referred to as the ‘land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF)’ sector according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) classification. Within this sector, forests remove CO2 from the air (as trees capture CO2 through photosynthesis), which in most Member States overcompensates for emissions from land use (for example, from the use of fertilisers) and land use change (for example, when grassland is converted to cropland).

Between 2008 and 2023, GHG net removals from land use and forestry fell by 44.5% in the EU. The strong decline in forest carbon sinks has been attributed to several trends, including slowdowns in net afforestation and in forest biomass growth as well as increases in tree mortality and in timber harvesting [3]. In the short-term period between 2018 and 2023, the EU’s net removals from land use and forestry declined by 2.3%. Due to the reductions in total GHG emissions, net removals still compensated for more than 6% of emissions in 2023. In absolute numbers, net removals amounted to 198.4 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2-equivalent in 2023. This is far below the EU’s net carbon removal target for land use and forestry of at least 310 Mt of CO2-equivalent by 2030.

Emissions associated with energy consumption have fallen thanks to reduced energy use and increased use of renewables

A sectoral breakdown of GHG emissions for 2023 shows that two sectors — energy industries (which covers electricity and central heat generation) and transport — were responsible for about half of total EU emissions, accounting for 24.3% and 25.6% of emissions, respectively. Industry and other energy consumers were the third and fourth largest emitters of GHGs in the EU, accounting for 20.2% and 14.3% of total emissions in 2023, respectively. Between 2018 and 2023, energy industries showed the strongest reduction in emissions, of 31.4%. Emissions from industry and from other energy consumers fell by 18.8% and 17.1%, respectively, while transport emissions dropped by 4.4% over the same period [4].

Emissions arise mainly from fossil energy consumption, whereby related reductions result from the general drop in energy consumption and an increasing share of renewable energies (see the article on SDG 7 ‘Affordable and clean energy’). In total, renewable energy contributed 24.6% of the EU’s gross final energy consumption in 2023. While this was an increase of 5.5 percentage points between 2018 and 2023, stronger progress is vital to reaching a 42.5% share of renewable sources in energy consumption by 2030. A sectoral breakdown shows that the share of renewables was largest in electricity generation, reaching 45.3% in 2023. The shares of renewables in heating and cooling and in transport were lower, at 26.2% and 10.8%, respectively, in 2023.

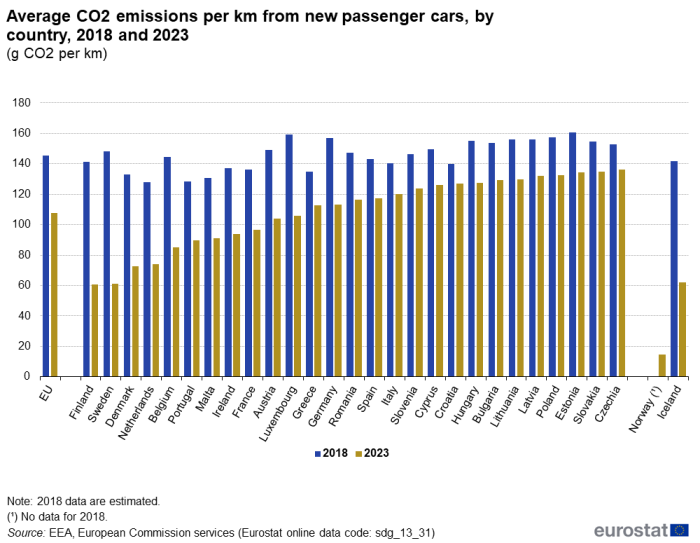

Average CO2 emissions per km from new cars have reached the lowest level recorded, but further reductions are needed to meet the 2030 target

Road transport was responsible for almost a quarter of the EU’s total GHG emissions in 2022, and more than half of road transport emissions came from passenger cars [5]. To reduce those emissions, the EU has set targets for the fleet-wide average CO2 emissions of new passenger cars, vans and heavy duty vehicles. The targets for average CO2 emissions per kilometre (km) from new passenger cars have been set to 93.6 grams per km (g/km) for the period 2025 to 2029 and to 49.5 g/km for 2030 to 2034, while from 2035 onwards the target is 0 g/km [6].

Over the period 2018 to 2023, the average CO2 emissions per km from new passenger cars registered in the EU fell by 26.1%, with most of this reduction taking place between 2019 and 2021. The EU average CO2 emissions reached 107.6 g/km in 2023. This is the lowest level on record but still far from the EU targets for 2025 and 2030.

Accelerating the market uptake of new zero-emission vehicles is a crucial step to achieving the CO2 emission targets. The share of zero-emission vehicles (mostly battery electric cars) in newly registered cars in the EU rose from 1.0% in 2018 to 14.5% in 2023. However, the share differs considerably between countries. Sweden reported the highest share with 38.6% in 2023, followed by Denmark with 36.1% and Finland with 33.8%. In contrast, zero-emission vehicles only accounted for around 3% of newly registered passenger cars in Czechia, Croatia and Slovakia [7].

Climate change impacts

Rising concentrations of CO2 emissions and other GHGs lead to global warming and increased ocean acidity. As a consequence of global anthropogenic GHG emissions, the decade 2013 to 2023 was the warmest on record, with a global mean near-surface temperature increase of 1.19–1.22 °C compared with the pre-industrial level. This means that more than half of the warming allowed under the Paris Agreement has already occurred. This agreement aims to keep the rise in global temperature well below 2° C and to continue efforts to limit warming to 1.5° C. However, the average annual temperature over the European continent has increased by more than this, by 2.12–2.19 °C during this decade [8].

Climate impacts are a consequence of rising temperatures and the related intensity and quantity of extreme events which affect environmental, social and economic systems. The EU’s SDG monitoring focuses on the economic costs that arise from weather- and climate-related extreme events. To minimise the impacts, countries are taking action to adapt to climate change by introducing measures such as flood protection, adapted agricultural practices and forest management, and sustainable urban drainage systems. However, adaptation is lagging far behind the impacts.

Economic losses from weather- and climate-related extreme events have continued to rise significantly

Studies have shown that various weather- and climate-related extreme events in Europe and beyond have become more severe and frequent as a result of global climate change. The resulting impact on human systems and ecosystems has led to measurable losses to nature, economies and people’s livelihoods [9]. Reported economic losses generally include monetised direct damages to certain assets and as such only partially estimate the full damages. They do not consider losses related to productivity, mortality and health, cultural heritage or ecosystems services, which would considerably raise the estimate [10].

Over the period 1980 to 2023, weather- and climate-related losses accounted for a total of 738 billion [11]. 2023 marked another negative year with climate-related economic losses amounting to EUR 43.9 billion, most of which (EUR 25.7 billion) was caused by hydrological events such as floods. This marks the third year in a row with economic losses well above the long-term trend. In 2021, losses had amounted to EUR 63.0 billion, mainly caused by extreme floods after record precipitation in central Europe. In 2022, EUR 56.0 billion had been lost, caused mainly by climatological events such as heat waves, droughts and forest fires.

However, recorded losses vary substantially over time: about 61% of the total losses have been caused by just 5% of unique extreme events [12]. This variability makes the analysis of historical trends difficult. A closer look at a 30-year moving average shows an almost steady increase in annual climate-related economic losses, from EUR 12.8 billion in 2009 to EUR 20.1 billion in 2023 [13], corresponding to a 57.7% increase. Over the period from 1980 to 2023, hydrological hazards (floods) accounted for 44% of economic losses in the EU, followed by meteorological hazards (storms, including lightning and hail) with 29% and heat waves with 19%. The remaining 8% was caused by droughts, forest fires and cold waves [14].

Financing climate action

As part of the transition towards climate neutrality and climate resilience, the EU is endeavouring to redirect public and private investments to areas where they will support this objective. For this reason, the EU has adopted the EU taxonomy as a classification system for sustainable economic activities and a European green bond standard as a voluntary ‘gold’ standard for the green bond market. At the EU level, climate change mitigation and adaptation has been integrated into all major spending programmes [15] and the EU has also committed to support international climate action.

Green bond issuance has shown an increasing trend despite dropping in 2023

Investments into clean technologies and supportive infrastructure are key for the transition to climate neutrality. Such investments often rely on funds which can be raised for example through the issuance of bonds. There are different issuers active in the green bond market such as the EU, which issues for example the NextGenerationEU Green Bonds to finance climate action in the EU.

The share of green bonds in total bond issuance increased sharply from 2.0% to 9.2% between 2018 and 2022 before dropping to 6.8% in 2023. In 2023, green bonds made up 7.1% and 5.9% of total bond issuance by corporates and governments respectively, compared with 1.7% and 3.0% in 2018. While for governments the share of green bonds in 2023 was the highest on record, for corporates the share fell in 2023 compared to the peak of 11.1% in 2022.

The issuance of green bonds by corporates and governments increased significantly in most EU Member States between 2018 and 2023. Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Austria saw substantial growth in green bond issuance, with these bonds accounting for more than 15% of total bonds issuance in 2023. In contrast, several countries from eastern and southern Europe exhibited little to no activity in this period.

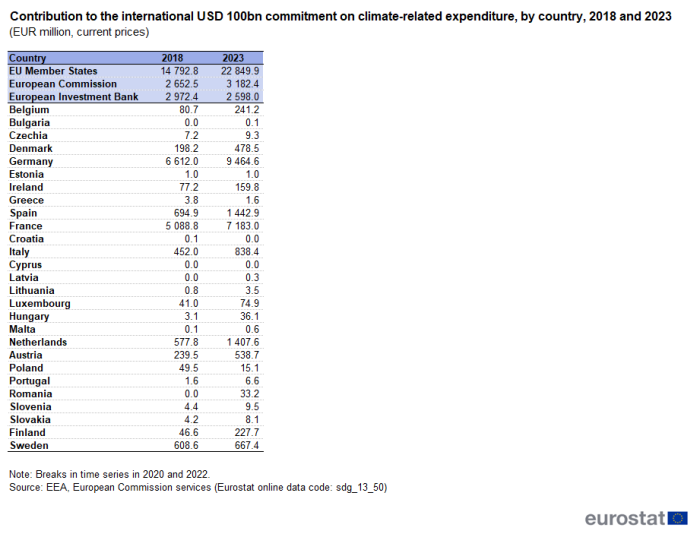

The EU’s contribution to climate finance for developing countries has been increasing since 2014

In addition to investing in climate action within its borders, the EU and its Member States have also committed to raising money to help developing countries combat climate change and adapt to climate impacts. They take part in a commitment made by the world’s developed countries to jointly mobilise USD 100 billion per year by 2025 [16] and in the fulfilment of the New Collective Quantified Goal of securing at least USD 300 billion per year by 2035 for developing countries, from a wide variety of sources, instruments and channels, with developed countries taking the lead [17].

Total EU public finance contributions (including all 27 Member States as well as the EU institutions) increased from about EUR 12.9 billion in 2014 to EUR 28.6 billion in 2023. This equals roughly USD 32 billion contribution to the global target. The two largest EU contributors in the period were Germany and France. The European Commission and the European Investment Bank (EIB) were the third and fourth largest donors in 2023, respectively. In 2023, the EU, its Member States and the EIB together were the biggest contributors of public climate finance to developing countries worldwide [18].

Main indicators

Net greenhouse gas emissions

This indicator measures man-made greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as well as carbon removals on EU territory. The ‘Kyoto basket’ of GHGs includes carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O) and the so-called F-gases F-gases, i.e., hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, nitrogen trifluoride (NF3) and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6). Emissions and removals are integrated into a single indicator — net GHG emissions — expressed in units of CO2 equivalents based on the global warming potential (GWP) of each gas. At present, carbon removals are accounted for only in the land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector. At the EU level, the scope of the data used is aligned with the scope of EU climate policies and the target to reduce GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990. Estimated emissions from international aviation and maritime transport are included and calibrated for this purpose. At country level, emissions from international transport are excluded.

The indicator refers to GHG emissions in the EU territory. GHG emissions derived from the production of goods imported and consumed in the EU are counted in the export country, following the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) rules. Emissions and removals data, known as GHG inventories, are submitted annually by Member States to the EU and the UNFCCC. The European Environment Agency (EEA) compiles the EU aggregate data and publishes data for the EU and all Member States. Eurostat republishes the EEA data.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: EEA, Joint Research Centre, Eurostat (sdg_13_11)

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: EEA, Eurostat (env_air_gge)

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_13_10)

Net greenhouse gas emissions from land use, land use change and forestry

This indicator measures net carbon removals from the land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector, considering both emissions and removals from the sector. The indicator is expressed as CO2 equivalents using the global warming potential (GWP) of each gas. Emissions and removals data, known as greenhouse gas (GHG) inventories, are submitted annually by Member States to the EU and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The European Environment Agency (EEA) compiles the EU aggregate data and publishes data for the EU and all Member States. Eurostat republishes the EEA data.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_13_21)

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_13_21)

Average CO2 emissions per km from new passenger cars

This indicator is defined as the average carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per km from new passenger cars registered in the EU in a given year. The reported emissions are based on emission tests during type-approval and can deviate from the actual CO2 emissions of those cars on the road. Data up to (and including) 2019 were determined according to the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) procedure, while the data collected from 2021 onwards is based on the World Harmonised Light-vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP). For 2020, data were collected for both test procedures. For the purpose of monitoring progress in this report, emission data for 2017 to 2019 are presented according to WLTP based on a conversion factor, which was calculated from the 2020 data in NEDC and WLTP. Data before 2017 are presented according to NEDC. Data presented in this section are provided by the European Commission, Directorate-General for Climate Action and the European Environment Agency (EEA).

Source: EEA, European Commission services, Eurostat (sdg_13_31)

Source: EEA, European Commission services, Eurostat (sdg_13_31)

Source: Eurostat, EAFO (road_eqr_zev)

This indicator includes the overall monetary losses from weather- and climate-related events. The European Environment Agency (EEA) compiles the EU aggregate data from CATDAT of RiskLayer. Eurostat republishes the EEA data. Due to the variability of the annual figures, the data are also presented as a 30-year moving average to facilitate the analysis of historical trends.

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_13_40)

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_13_40)

Green bond issuance

Green bonds are loans provided by an investor to a borrower which are used to fund projects or activities that promote climate change mitigation or adaptation or other environmental objectives. While the green bond definition can vary, this indicator includes bonds that are aligned with the four core components of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) green bond principles or are certified by the Climate Bond Initiative (CBI) [19]. Issuers include cooperates such as a company or financial corporation and sovereign bond issuers which are national governments.

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_13_70)

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_13_70a)

The intention of the international commitment on climate finance under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is to enable and support enhanced action by developing countries to advance low-emission and climate-resilient development. The data presented in this section are reported to the European Commission under the Monitoring Mechanism Regulation (Regulation (EU) 525/2013) for the period up to 2019 and under the Governance Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2018/1999) for subsequent years. Data from 2020 onwards thus cover commitments for both multilateral and bilateral public finance and are not fully comparable with earlier years. In addition, since 2022, the methodology is based on commitments for bilateral finance and disbursements of multilateral finance made in the same year. The data refer to public finance only and do not include private finance.

Source: EEA, European Commission services (sdg_13_50)

Source: EEA, European Commission services (sdg_13_50)

Footnotes

- ↑ The data presented here cover GHG emissions produced inside the EU territory and do not take into account those that occurred outside the EU as a result of EU consumption. At the EU level, the scope of the data used is aligned with the scope of EU climate policies and the target to reduce GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990. Estimated emissions from international aviation and maritime transport are included and calibrated for this purpose.

- ↑ The data on Member States’ net GHG emissions exclude international transport and international maritime transport, while these are partly included in the EU data.

- ↑ See for example: ESABCC (2024), Towards EU climate neutrality—Progress, policy gaps and opportunities, European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change; and Hyyrynen, M., Ollikainen, M., & Seppälä, J. (2023), European forest sinks and climate targets: Past trends, main drivers, and future forecasts, European Journal of Forest Research, 142(5), 1207–1224.

- ↑ Eurostat (env_air_gge).

- ↑ Eurostat (env_air_gge).

- ↑ European Commission (2023), Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2023/1623 of 3 August 2023 specifying the values relating to the performance of manufacturers and pools of manufacturers of new passenger cars and new light commercial vehicles for the calendar year 2021 and the values to be used for the calculation of the specific emission targets from 2025 onwards.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat and European Alternative Fuels Observatory (road_eqr_zev).

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2024), Global and European temperatures.

- ↑ IPCC (2023), Climate change 2023 – Synthesis Report – Summary for Policymakers, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-34.

- ↑ IPBES (2019), Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn; and European Environment Agency (2016), Climate change impacts and vulnerability in Europe: An indicator-based report, Report No. 1/2017, Copenhagen.

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2024), Economic losses from climate-related extremes in Europe.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ A 30-year moving average shows the average over the past 30 years for a given year. For example, for 2017, the data point shows the average from 1988 to 2017.

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2024), Economic losses from climate-related extremes in Europe.

- ↑ European Commission, The EU long-term budget.

- ↑ European Commission (2018), A modern budget for a Union that protects, empowers and defends: The Multiannual Financial Framework for 2021–2027, COM(2018) 321 final, Brussels.

- ↑ UNFCCC (2024), COP29 UN Climate Conference Agrees to Triple Finance to Developing Countries, Protecting Lives and Livelihoods.

- ↑ European Council (2025), Europe's contribution to climate finance (in €bn).

- ↑ EEA (2024), Green bonds.

Explore further

Other articles

Database

Thematic section

Publications

Further reading on climate action

- European Commission, Climate Action.

- European Commission (2024), Climate Action Progress Report 2024 – Leading the way: from plans to implementation for a green and competitive Europe.

- European Commission, Climate Action – 2050 long-term strategy.

- EEA (2024), Urban adaptation in Europe: what works?

- EEA (2024), Trends and projections in Europe 2024, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen.

- EEA (2018), National climate change vulnerability and risk assessments in Europe, 2018, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen.

- IPCC (2023), Climate Change 2023 Synthesis Report – Summary for Policymakers.

Methodology

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2025 edition’.

External links

Further data sources on climate action

- EEA, Greenhouse gas data viewer.

- EEA, EEA greenhouse gas projections — data viewer.

- EEA, EEA database on integrated national climate and energy policies and measures in Europe.

- Global and European temperatures.

- European Automobile Manufacturers Association, Interactive map: Affordability of electric cars, correlation between market uptake and GDP in the EU.

- Eurostat, Climate change.

- Eurostat, Environmental accounts dashboard.