Material deprivation statistics - early results

Data extracted in April 2020.

No planned article update.

Highlights

In 2019, the EU-27 severe material deprivation rate for people aged less than 18 years was the same (5.8 %) as for persons aged 18-64 years. In all previous years (2010-2018) the rate for younger people had been higher.

Among the EU Member States, the share of people unable to face unexpected expenses fell most between 2018 and 2019 in Latvia and Estonia.

Among the EU Member States, the share of people unable to afford a week’s annual holiday fell most between 2018 and 2019 in Cyprus, Latvia and Romania.

Among the EU Member States, the share of people unable to afford a meal with meat, fish, chicken or a vegetarian equivalent every other day fell most between 2018 and 2019 in Bulgaria, Lithuania and Slovakia.

Share of the population unable to face unexpected financial expenses, 2019

Increased timeliness of the EU-SILC data

Since 2014, Eurostat disseminates early results for severe material deprivation rates so that trends in poverty levels can be tracked more closely. The coverage and the timeliness of these statistics have increased over the years. At the time of writing, 21 European Union (EU) Member States and Norway had already submitted 2019 EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). Bulgaria, Denmark, Latvia, Hungary, Poland and Finland have provided final data, while Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Greece, France, Croatia, Cyprus, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Norway have transmitted provisional data. This article is based on data sent to Eurostat by the middle of April 2020.

Full article

Severe material deprivation rate: variations between countries

Box 1: Material deprivation rates

Material deprivation rates gauge the proportion of people whose living conditions are affected by a lack of resources. More precisely, material deprivation rates represent the proportion of people living in households that cannot afford a certain number of the following nine items:

- mortgage or rent payments, utility bills, hire purchase instalments or other loan payments;

- one week’s holiday away from home;

- a meal with meat, chicken, fish or a vegetarian equivalent every second day;

- unexpected financial expenses;

- a telephone (including mobile telephone);

- a colour television (TV);

- a washing machine;

- a car; and

- heating to keep the home adequately warm.

The severe material deprivation rate, broken down by sex, age group and household type, is the main indicator for material poverty in this article. It is calculated as the proportion of people living in households that cannot afford at least four of the nine items listed in Box 1.

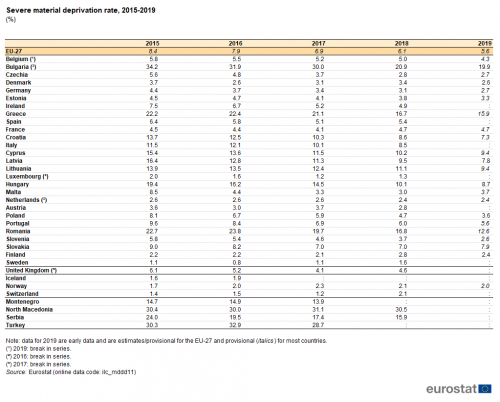

In 2019, the rate of severe material deprivation in the EU-27 was 2.8 percentage points lower than in 2015, down from 8.4 % to 5.6 %. This rate varied substantially between EU Member States (see Table 1):

- in 2019, the highest rates were 19.9 % in Bulgaria, 15.9 % in Greece and 12.6 % in Romania, while the lowest rates, all between 2.7 % and 2.4 % were in Czechia, Germany, Denmark, Slovenia, the Netherlands and Finland;

- in general between 2015 and 2019, the highest rates among the EU Member States were recorded in Bulgaria (decreasing from 34.2 % in 2015 to 19.9 % in 2019), Romania (peaking at 23.8 % in 2016 and in excess of 10.0 % for all years between 2015 and 2019) and Greece (peaking at 22.4 % in 2016 and in excess of 10.0 % for all years between 2015 and 2019).

The proportion of the severely materially deprived population was lower in almost all EU Member States in 2019 than it had been in 2015. The two exceptions were France and Finland where the 2019 rates were only slightly (0.2 percentage points) higher than those observed in 2015. Between 2015 and 2019, the largest decreases in the severe material deprivation rate were observed in Bulgaria (down 14.3 percentage points), Hungary (down 10.7 points) and Romania (down 10.1 points), reflecting changes in the material living conditions in those Member States.

Looking at the most recent developments, in many of the countries that have already sent 2019 data to Eurostat a decrease can be observed in severe material deprivation rates between 2018 and 2019. The exceptions were Slovakia and Malta where the rates increased by 0.9 and 0.7 percentage points respectively: in Slovakia the rate increased from 7.0 % to 7.9 % while in Malta it increased from 3.0 % to 3.7 %. In France (4.7 %) and the Netherlands (2.4 %) the rates remained stable. The largest decrease was registered in Romania (down 4.2 points from 16.8 % to 12.6 %), followed by Latvia and Lithuania (both down 1.7 points).

Severe material deprivation by household type

These early results for severe material deprivation rates in 2019 confirm a pattern seen in previous years, namely a higher incidence of severe material deprivation among:

- people living in households composed of a single person with dependent children;

- single person households (whether a single man or a single woman); and

- households composed of two adults with three or more children.

Among the six selected types of households shown in Table 2, households with two adults and one dependent child were the least likely to experience severe material deprivation in 2019 in Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia. In the remaining EU Member States for which data are available — Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Greece, France, Cyprus, Hungary, the Netherlands and Finland — as well as in Norway, the lowest severe material deprivation rates among these six types of households were reported for households comprised of two adults where at least one was aged 65 years or over.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddd13)

Severe material deprivation by age

In most of the recent years, severe material deprivation in the EU-27 was most common among persons aged less than 18 years while it was least common among older persons (aged 65 years or over), with the rate for persons of working age (18 to 64 years) between these two extremes. However, from Table 3 it can be seen that in 2019 this situation changed, as the early results show that the rate for younger people was the same as that for the working age population, 5.8 % in both cases. The rate for older people remained lower, at 4.8 %. Between 2015 and 2019, the severe material deprivation rate for young people in the EU-27 fell from 9.6 % to 5.8 %, a fall of 3.8 percentage points. During the same period, the rate for the working age population fell from 8.7 % to 5.8 %, a fall of 2.9 points. For older people, the rate fell 1.3 points, from 6.1 % to 4.8 %.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddd11)

Between 2018 and 2019 the severe material deprivation rate for people aged less than 18 years increased in Malta (up 0.8 percentage points) and was almost unchanged in the Netherlands (up 0.1 points) and Portugal (down 0.1 points). The rate for this age group fell elsewhere among the EU Member States for which 2019 data are available (as well as in Norway), down by at least 1.0 points in nine Member States, most notably in Hungary (down 2.1 points), Latvia (down 2.3 points) and particularly Romania (down 4.5 points).

The rate for the working age population (aged 18 to 64 years) increased between 2018 and 2019 by 1.2 percentage points in Slovakia, 0.9 points in Malta and 0.3 points in the Netherlands, while it was relatively unchanged in Czechia (up 0.1 points), France (no change) and Norway (down 0.1 points). Elsewhere the severe material deprivation rate for working age people fell. Eight EU Member States reported a rate for this subpopulation in 2019 that was at least 1.0 points lower than it had been the year before, with the largest decrease in Romania (down 3.9 points).

Between 2018 and 2019, increases in the severe material deprivation rate for older people (aged 65 years or over) were recorded in four EU Member States: Slovakia (up 0.9 percentage points), France, Hungary (both up 0.4 points) and Denmark (up 0.3 points); there was also an increase in Norway (up 0.5 points). The rate was relatively unchanged (down 0.1 points) in Belgium (note that there is a break in series), Germany and Finland, while larger decreases were reported elsewhere. The rate for older people fell by more than 1.0 points in six Member States, including falls of 2.7 points in Lithuania, 3.6 points in Bulgaria and 4.5 points in Romania. As such, Romania recorded the largest falls between 2018 and 2019 for all three age groups shown in Table 3.

Factors of material deprivation

As in previous years, the early results for 2019 show that severe material deprivation rates are determined mainly by changes in the ability to afford:

- unexpected financial expenses; or

- one week’s holiday away from home; or

- a meal with meat, fish, chicken or a vegetarian equivalent every second day.

These items, for which deprivation rates are highest, are also those that are not durable investment items, but are largely covered (or not) by monetary income or savings available for household expenditure. Rate changes for these items thus provide an early indication of changes in the monetary situation of households.

In 2019, the percentage of people in the EU-27 who said they were unable to face unexpected expenses was lower compared with 2017 and 2018, down from 34.0 % in 2017 to 32.2 % in 2018 and 31.5 % in 2019 (see Figure 1). Focusing on the change between 2018 and 2019, four EU Member States observed an upward development for this share, with increases of 4.4 percentage points in Bulgaria, 0.8 points in Belgium (note that there is a break in series) as well as in Malta, and 0.3 points in the Netherlands; Norway recorded a larger increase, its share rising by 5.0 points. The remaining 17 EU Member States for which 2019 data are available recorded lower shares of their populations unable to face unexpected financial expenses in 2019 compared with 2018. A total of 13 Member States reported falls of at least 1.0 points, among which six reported their shares falling by at least 2.0 points, peaking at 3.3 points in Estonia and 5.5 points in Latvia.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdes04)

In a similar manner, the share of the EU-27 population that cannot afford to go on a week’s annual holiday decreased between 2017 and 2018 and again between 2018 and 2019, down from 31.0 % in 2017 to 28.5 % in 2019 (see Figure 2). Almost all EU Member States for which 2019 data are available reported a decrease in this share between 2018 and 2019, the exceptions being Bulgaria where the share increased by 5.0 percentage points and the Netherlands where a more modest increase (0.2 points) was recorded; an increase of 0.8 points was also observed in Norway. Of the 19 Member States where the share of the population that could not afford to go on a week’s annual holiday fell, 16 recorded falls of at least 1.0 points, with seven of these exceeding 2.0 points. The largest downward changes in this share were in Romania (down 4.8 points), Latvia (down 5.1 points) and Cyprus (down 5.8 points).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdes02)

Between 2017 and 2019, the percentage of people in the EU-27 who said they could not afford a meal with meat, fish, chicken or a vegetarian equivalent every second day decreased by 1.4 percentage points, from 8.4 % in 2017 to 7.4 % in 2018 and 7.0 % in 2019 (see Figure 3). Nevertheless, in several Member States this share increased compared to 2018: Estonia (up 0.9 points), Denmark, Hungary (both up 0.7 points), France (up 0.6 points), the Netherlands (up 0.3 points) and Malta (up 0.2 points); there was also an increase of 0.4 points in Norway. In Greece (up 0.1 points) and Portugal (down 0.1 points) there was almost no change. The share of people who said they could not afford a meal with meat, fish, chicken or a vegetarian equivalent every second day fell by less than 1.0 points in a further four Member States, by 1.2 points in Cyprus and by 2.0 points or more in eight Member States, including Slovakia, Lithuania (both down 2.8 points) and Bulgaria (down 3.8 points).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdes03)

Making ends meet

The economic strain variable making ends meet is included in the early transmission of data. It is related to current income and enables the timely detection of trends in monetary poverty.

The 2019 data are broadly consistent with the situation in previous years (see Table 4); in other words:

- in most EU Member States, the highest proportion of people said that they had either some difficulties or that it was fairly easy for them to make ends meet (medium ability to make ends meet);

- Greece and Bulgaria were the only Member States with the highest proportion of people declaring difficulties or great difficulties in making ends meet (low ability to make ends meet); and

- the highest proportion of people who could make ends meet easily or fairly easily (high ability to make ends meet) were found in the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany, as well as in Norway.

The main changes between 2018 and 2019 concerning the ability to make ends meet were:

- large decreases in the proportion of people who had difficulty or great difficulty in making ends meet (low ability) in Cyprus (down 9.3 percentage points), Croatia (down 7.2 points), Latvia (down 7.1 points), Hungary (down 6.7 points) and Bulgaria (down 5.8 points), while this share fell in a further 11 EU Member States;

- increases in the proportion of people who had difficulty or great difficulty in making ends meet in four Member States, exceeding 1.0 points only in Slovakia (up 2.9 points);

- increases of 1.0 points or more in the proportion of people who could make ends meet easily or very easily (high ability) in 12 Member States, with the highest increases in Denmark (up 2.9 points), Poland (up 3.1 points), Cyprus and Czechia (both up 3.4 points);

- decreases in the proportion of people who could easily or very easily make ends meet in three Member States — Finland (down 0.5 points), Slovakia (down 0.6 points) and the Netherlands (down 1.1 points) — as well as in Norway (down 4.9 points).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

EU-SILC, established under framework Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003, is the reference source for statistics and indicators on income and living conditions. It is a multi-purpose instrument that focuses mainly on income, collecting detailed income components at household and individual level, but also gathers information on social exclusion, material deprivation, housing conditions, labour market participation, education and health.

Monetary income is one of the most relevant factors for measuring poverty and inequality, but wealth and consumption levels are also relevant, linked as they are to material deprivation, in other words the inability to afford goods and services and/or to engage in activities seen by society as ordinary or necessities.

Currently, by the time statistics have been processed and indicators disseminated, EU-SILC final data have a lag of almost two years in the case of monetary income data and 1 to 1.5 years in the case of non-monetary information. This has profound implications for EU-SILC’s usefulness for policy purposes, especially in times of rapid socioeconomic change.

Since the March 2000 Lisbon Summit, Member States and the European Commission have cooperated in the field of social policy on the basis of the ‘open method of coordination’ (OMC). To monitor the social OMC, the EU and its Member States have adopted commonly agreed indicators, including in the area of material deprivation. In particular, the severe material deprivation rate is a component of the Europe 2020 at risk of poverty or social exclusion headline indicator, calculated as the total number of persons at risk of poverty, severely materially deprived or living in households with very low work intensity.

More recently, the need for early estimates of material deprivation was highlighted in the European Commission’s Communication Towards Social Investment for Growth and Cohesion — including implementing the European Social Fund 2014-2020 (COM (2013) 83 final).

Nine EU Member States sent Eurostat a first set of provisional statistics for material deprivation and economic strain in 2012, so that Eurostat could carry out a feasibility study on calculating relevant variables and indicators. Its main conclusions were that the computation of provisional material deprivation indicators was feasible and that preliminary/early results were close to final material deprivation values. It found that there were two main reasons for discrepancies between the early results and final values:

- the application of preliminary cross-sectional EU-SILC weightings, as not all information needed to work out final weightings was available at the end of the data collection year; and

- for some Member States, data editing could be finalised only partially by the submission date for early results.

All EU-SILC microdata transmitted to Eurostat must contain individual and household weightings. In all household surveys, mainly because of non-response, some groups are over-represented and others under-represented in the raw data. These imbalances are usually dealt with by attaching a compensatory weighting to members of sub-groups considered to be over- or under-represented in the survey data.

All survey estimates are calculated using these weightings. Data are calibrated to align totals from the survey to known totals from reliable external sources such as recent population statistics, including information on age, gender, regional breakdowns, the labour force, and so on. Not all these variables may be fully available to national statistical authorities at the time the early material deprivation variables have to be transmitted, in other words at the beginning of the year after data collection. The information used to construct the cross-sectional household and individual weightings is specific to each EU Member State and decided nationally [1]. Several procedures are applied to construct the provisional weightings, which might (as the study showed) come very close to the final weightings.

In Eurostat’s online database, provisional indicators are flagged p (provisional) to distinguish them from final data. For the countries for which only provisional data are available, the analysis is merely indicative.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

Context

The global financial and economic crisis threw up a number of challenges for official statistics and social statistics in particular, where the timeliness of data and indicators became a key issue of debate.

Eurostat (together with the EU Member States) initiated the transmission of early results on material deprivation and economic strain variables collected through the EU-SILC survey in response to the urgent needs of social policymaking. Although monetary poverty is one of the most relevant factors when assessing poverty and social inclusion, material deprivation is also an important descriptor of the difficulties households face in achieving a standard of living that is considered by society to be ‘normal’.

Material deprivation data and indicators are absolute measures that can be used to analyse and compare aspects of poverty within and among EU Member States. Currently, data based on early results are available during the spring of the year following the survey year and cover three quarters of the Member States. To supplement these early results on material deprivation Eurostat develops flash estimates of the main EU-SILC indicators as experimental statistics.

Notes

- ↑ More information can be found in the national quality reports.

Direct access to

Statistical articles

- Children at risk of poverty or social exclusion

- Living conditions in Europe - income distribution and income inequality

- Living conditions in Europe — online publication

- Migrant integration statistics — at risk of poverty and social exclusion

- Quality of life indicators — material living conditions

Methodological articles

- Material deprivation (t_ilc_md)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Material deprivation by dimension (ilc_mddd)

- Economic strain (ilc_mdes)

- Living conditions in Europe — 2018 edition

- Monitoring social inclusion in Europe — 2017 edition

Statistics

- Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003 of 16 June 2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation (EC) No 1553/2005 of 7 September 2005 amending Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

- Regulation (EC) No 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006 adapting certain Regulations and Decisions in the fields of ... statistics, ..., by reason of the accession of Bulgaria and Romania

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/2256 of 4 December 2015 amending Regulation (EC) No 1983/2003 implementing Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) as regards the list of target primary variables

- Summaries of EU Legislation: EU statistics on income and living conditions

Social investment

- Communication COM (2013) 083 final of 20 February 2013 towards Social Investment for Growth and Cohesion – including implementing the European Social Fund 2014-2020