Archive:Enlargement countries - finance statistics

Data from May 2021.

Planned article update: April 2022.

Highlights

Three of the EU candidate countries and potential candidates — Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia — recorded government budget deficits every year between 2009 and 2020.

Between 2014 and 2020, the highest annual consumer price increases among the EU candidate countries and potential candidates were recorded in Turkey.

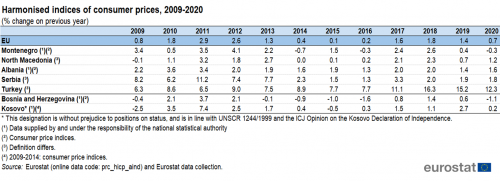

Harmonised indices of consumer prices, 2009-2020

This article is part of an online publication and provides information on a range of financial statistics for the European Union (EU) candidate countries and potential candidates, in other words the enlargement countries. Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Turkey currently have candidate status, while Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as Kosovo* are potential candidates.

The article provides information on price and finance statistics, covering consumer price indices; interest rates; foreign exchange rates; the balance of payments, including foreign direct investment (FDI); and government finance: the general government deficit/surplus and government debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP).

Full article

Consumer prices

A consumer price index measures changes in the prices of a representative set of goods and services consumed by households. It is an important measure of inflation. In the European Union, the harmonised index of consumer prices provides a consumer price index that is directly comparable between countries.

Changes in the Harmonised index of consumer prices and in national consumer price indices are shown in Table 1 and in the graph in the Highlights section above.

(% change on previous year)

Source: Eurostat (prc_hicp_aind)

Consumer prices in most of the candidate countries and potential candidates generally increased more in the period 2010-2012 than subsequently. Consumer price rises in Serbia, during the period 2009-2013, and in Turkey, during the whole period 2009-2020, were higher than those recorded across the other candidate countries and potential candidates, as well as in the EU. There does not seem to be any discernible effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer price changes in 2020.

In Serbia, consumer price inflation was higher during the period 2009-2013 than subsequently. Serbia’s inflation high point during the 2009-2020 period was in 2011 at 11.2 % and its low point in 2016 at 1.3 %. After 2013, the highest consumer price rise recorded for Serbia was 3.3 % in 2017. In 2020, consumer prices rose by 1.8 %.

In Turkey, peak consumer price inflation occurred in 2018, at 16.3 %, at a time when price increases in the other candidate countries and potential candidates were around the average for the whole period and lower than they had been during 2009-2012. Turkish consumer price inflation has moved higher during 2017-2020. The lowest annual consumer price increase during the period 2009-2020 was recorded in 2009, at 6.3 %. In 2020, consumer prices rose by 12.3 %.

Albania’s consumer price increase high point over the period 2009-2020 was 3.6 % in 2010 and low point 1.3 % in 2016, a fairly narrow range. The years 2010 and 2011, in which year the consumer price index rose by 3.6 % and 3.4 %, respectively, can be seen as deviating from the rest of the period. After 2011, the highest increases of consumer prices, by 2.0 %, were recorded in 2012, 2017 and 2018. In 2020, consumer prices rose by 1.6 %.

Bosnia and Herzegovina had a similar pattern of consumer price changes over the period 2009-2020. The largest annual consumer price increase at 3.7 % occurred in 2011; the next largest, 2.1 %, in both 2010 and 2012. Subsequently, price changes lay in the range -1.6 %, occurring in 2016, to 1.4 %, in 2018. In 2020, consumer prices fell by -1.1 %.

Kosovo also had higher inflation in the period 2010-2012, peaking at 7.4 % in 2011. Following this, changes in the consumer price level were within the narrow range -0.5 % (2015) to 1.7 % (2013), except in 2019, when the change was 2.7 %. Note also that consumer prices in Kosovo fell by -2.5 % in 2009. In 2020, consumer prices rose by 0.2 %.

Consumer prices in Montenegro from 2013 to 2020 have changed by between -0.7 % (2014) and 2.6 % (2018). During the earlier period 2009-2012, consumer price rises in Montenegro were generally higher, although they rose by only 0.5 % in 2010. The largest increase was in 2012 at 4.1 %. In 2020, consumer prices fell by -0.3 %.

North Macedonia has had rather stable consumer prices, with the low during the period 2009-2020 occurring in 2009 at -0.1 % and the high in 2011 at 3.2 %. In 2020, consumer price rose by 1.2 %.

Increases in the all-items harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) remained at low levels across the EU during the period 2009-2020, rising between 0.1 % in 2015 and 2.9 % in 2011, coinciding with the recovery from the global financial crisis. In 2020, consumer prices rose by 0.7 %. The somewhat higher increase in EU consumer prices in 2011 can be seen reflected in most of the candidate countries and potential candidates, with the exception of Turkey. The EU price changes, covering all 27 Member States, can to a limited extent be compared with the European Central Bank inflation aim of below, but close to, 2 % a year for the euro area, which since 2015 has comprised 19 Member States.

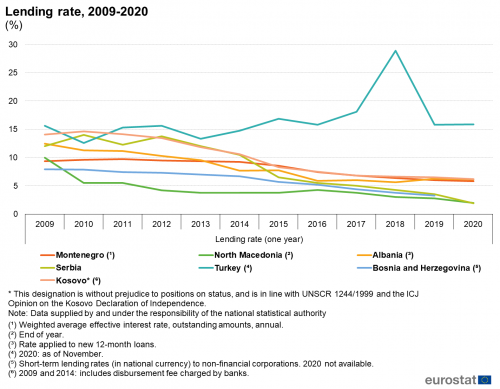

Interest rates

An interest rate is the cost of borrowing or the gain from lending, normally expressed as an annual percentage amount. The central bank interest rate is the official rate at which the European Central Bank and national central banks lend money to commercial banks for very short periods. This rate is an instrument for influencing interest rates in the economy and inflation. Interest and inflation rates are therefore closely linked. Countries can manage their interest rates either to target inflation or currency exchange rates.

The lending rate, illustrated in Figure 1, is the interest rate charged in the wholesale ‘money market’ for loans or transactions in liquid (easily marketable) financial securities of one year’s duration. This provides the ceiling on money market interest rates. In countries where the financial markets are less developed, the lending rate is the interest rate charged by central banks to commercial banks for short term funding against marketable financial securities. The lending rate is higher than both the deposit rate and the central bank interest rate. Bank loans to large low-risk companies are at an interest rate linked to but higher than the lending rate. Bank lending to clients that are perceived as being greater risks normally entail still higher interest rates.

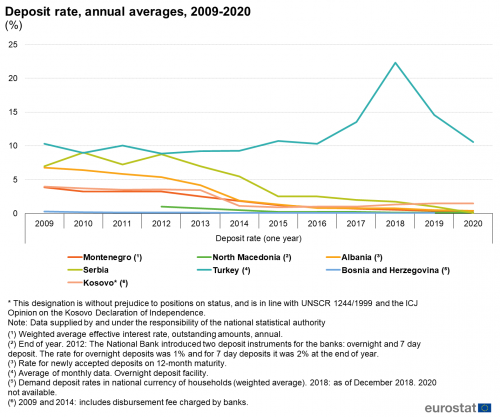

The deposit rate, as illustrated in Figure 2, is the annualised interest rate which the central bank pays on short-term deposits by banks or pays for short-term liquid financial instruments (bills). It is below the interest rate which banks can obtain on the money market and so forms the floor for money market interest rates. The deposit rate is closely related to the official bank rate.

The lending rate declined over the period 2009-2020 in most candidate countries and potential candidates under the influence of the recovery from the 2008 global financial crisis, the subsequent reduction in inflation from 2013 onwards and loose monetary policy within the EU.

Turkey was clearly an outlier over the period 2009-2020, with an average lending rate of 16.6 %, a maximum of 28.9 % in 2018, long after other candidate countries and potential candidates had passed their peak, and a minimum of 12.6 % in 2010. The average, maximum and minimum rates were all the highest in the region. Kosovo’s average lending rate over the period 2009-2020 was 10.1 %; its highest rate was 14.6 % in 2010 and its lowest 6.2 % in 2020.

Serbia, at 8.4 %, Albania, at 8.3 %, and Montenegro, at 8.1 %, had similar average lending rates over the period 2009-2020. Serbia’s maximum lending rate was 14.0 % in 2010, and its minimum, 1.9 % in 2020. Albania’s maximum rate was 12.5 % in 2009, its minimum 5.7 % in 2018 and its most recent 6.1 % in 2020. Montenegro’s maximum lending rate was 9.7 % in 2011 and its minimum was 5.8 % in 2020.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s average lending rate over 2009-2019 was 6.1 %, its maximum 7.9 % in 2009 and 2010 and its minimum 3.3 % in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available. North Macedonia’s average lending rate over the period 2009-2020 was 4.4 %, its maximum 10.0 % in 2009 and its minimum 2.0 % in 2020.

A similar decline in the deposit rate in most candidate countries and potential candidates can also be observed. These rates fell below 1 % in Montenegro (from 2016); North Macedonia (from 2013); Albania (from 2016); Serbia (2020); and Bosnia and Herzegovina, throughout the period, no data for 2020. Turkey is again an outlier. The difference between deposit and lending rates narrowed in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo.

As shown in the footnotes of Figure 2, comparisons are difficult between deposit rates in candidate countries and potential candidates. Nevertheless, the deposit rate in Turkey in 2020 was 10.6 %, about 1 percentage point below its average for the period but higher than elsewhere. In Kosovo, the deposit rate in 2020 was 1.5 %. Elsewhere, as stated above, it was below 1 %.

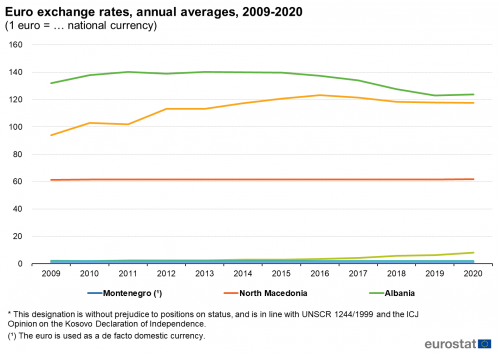

Exchange rates

One currency is exchanged for another at ‘foreign’ exchange rates. Montenegro and Kosovo have unilaterally adopted the euro as their de facto currency. Bosnia and Herzegovina has fixed its currency to the euro, so that there has been no change in the exchange rate over the period 2009-2020. Euro exchange rates for those candidate countries and potential candidates that have floating currencies (North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Turkey) are shown in Figure 3.

(1 euro = ... national currency)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a)

North Macedonia targets a fixed exchange rate for its currency, the denar, with the euro, although its value varied by 0.4 % in 2010, compared with 2009. The Serbian dinar depreciated against the euro by almost 9 % in 2010 and by 10 % in 2012. Smaller depreciations continued in 2014-2016, of which the maximum was 3.6 % in 2014, followed by somewhat appreciation in 2017-2018. It had also appreciated by 1.1 % in 2011. Over the period 2009-2020, the dinar depreciated against the euro by 20 %. The Albanian lek depreciated against the euro by over 4 % in 2010 and somewhat also the following year. It then appreciated during the period 2014-2019, notably by 5.1 % in 2018. By 2020, the lek had appreciated by 6.7 % against the euro, compared with 2009. Although the Turkish lira appreciated by 8.3 % in 2010 and again slightly in 2012, it has depreciated in every other year in the period in question, most notably by almost 28 % in 2018. Total depreciation against the euro over 2009-2020 was 73 %.

Balance of payments

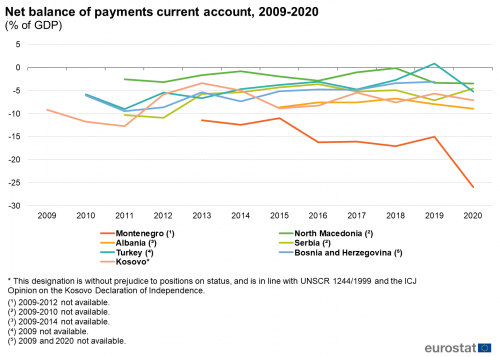

The current account of the balance of payments represents transactions with the rest of the world concerning merchandise, services, income and other current transfers. It is normal for countries that are very fast growing to run negative balances, which represent borrowing from the rest of the world. Developed countries often run surpluses, which represent building up assets in the rest of the world. A balance of payments deficit that is large compared with the country’s GDP can lead to financial difficulties. Data for the candidate countries and potential candidates is illustrated by Figure 4.

Data from North Macedonia is available from 2011 to 2020. The deficit exceeded 3 % of GDP on only three occasions during this period: in 2012 (3.2 %); in 2019 (3.3 %) and 2020 (3.5 %).

Serbian data is also available from 2011 to 2020. In 2011 and 2012, the payments deficit was respectively 10.3 % and 10.9 %. Since then, the largest payments deficit was recorded in 2019, at 7.1 %; and the smallest in 2016 at 3.6 %. The 2020 observation was a deficit of 4.5 %.

In Turkey, data is available from 2010. Other than in 2011, when the payments deficit was 9.0 % of GDP, and 2019, when there was a payments surplus of 0.9 %, the payments deficit ranged between 6.7 % in 2013 and 2.7 % in 2018. The most recent observation for 2020 was a payments deficit of 5.2 %.

Data for Bosnia and Herzegovina is available for 2010 to 2019. The largest payments deficit was in 2011, at 9.5 % of GDP; and the smallest, in 2019, was 3.1 %. 2012 saw the second largest payments deficit at 8.6 % of GDP. Thereafter, payments deficits mostly diminished to the range 3.1 % (2019) to 5.3 % (2013), although the 2014 payments deficit figure was 7.3 %.

High payments deficits were recorded in Kosovo between 2009 at 9.2 % of GDP and 2011, at 12.7 %, the largest during the period 2009-2020 for which data is available. During 2012-2014, the payments deficits diminished, the largest being in 2012 at 5.8 % and the smallest in 2013 at 3.4 %. Payments deficits then increased again in 2015 (8.8 %) but moderated in 2016 (8.2 %). The payments deficit then diminished slightly to a range of 5.4 % in 2017 to 7.6 % in 2018. The 2020 payments deficit was 7.1 %.

Albanian data is available 2015-2020. The largest balance of payments deficit was in 2020, at 8.9 % of GDP; and the smallest in 2018 at 6.7 %.

Data for Montenegro is available for 2013-2020. The payments deficit in 2013 was 11.4 % of GDP. Since then, there has been an almost continual deterioration in the payments deficit, with slight improvements in 2015, at a payments deficit of 11.0 %, and in 2019 at a payments deficit of 15.0 %. The 2020 figure was a balance of payments deficit equal to 25.9 % of GDP.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_c6_a) and (nama_10_gdp)

Foreign direct investment

Foreign direct investment (FDI) represents a lasting interest in an enterprise operating in another economy and implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the recipient enterprise. It forms a part of the financial account of the balance of payments. Inflows represent investment in the economy; outflows represent investment by the economy in the rest of the world. Negative values represent disinvestment. Countries that attract considerable inward investment are often themselves investors in other countries.

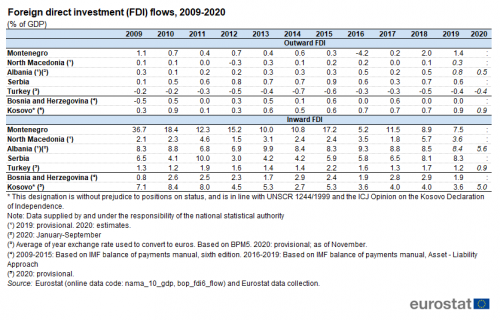

Table 2 shows outward and inward inflows of foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP for the candidate countries and potential candidates for the period 2009-2020. Each of the candidate countries and potential candidates for which data are available had a higher level of FDI inflows than outflows in every year of the period covered. Turkey, in every year covered, and Montenegro, in 2016, recorded negative flows of outward FDI. This represents disinvestment, which occurs when previous investments are withdrawn from the foreign enterprises; or funds flowing back from the foreign company to the parent; or negative reinvested earnings. Outward FDI accounts for a very small percentage of GDP in all the candidate countries and potential candidates. Worth noting was Serbia’s outward FDI of 0.9 % of GDP in 2015 and Kosovo’s similar 0.9 % of GDP in 2010, 2019 and 2020. Turkey, as previously noted, recorded negative flows of outward FDI, which reached their greatest magnitude at -0.7 % of GDP in 2014.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_flow), (nama_10_gdp) and Eurostat data collection

Montenegro had the largest inward foreign direct investment of the candidate countries and potential candidates as a percentage of its GDP. In 2009, inward FDI was equivalent to 36.7 % of its GDP. Thereafter, inward FDI almost continually diminished to 7.5 % of GDP in 2019, although the outcome in 2015 was 17.2 % of GDP and in 2017, 11.5 %. The next largest attractor of foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP was Albania. From 2009 to 2019, inward FDI accounted for between 6.8 % of GDP, in 2011, and 9.9 % in 2013. The 2020 figure was below this range, at 5.6 %.

Serbia saw peaks of inward FDI in 2011 at 10.0 %; in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, at 8.3 %; and 2018, at 8.1 %. 2012 was a low year for FDI at 3.0 % of GDP. In other years, inward foreign direct investment as a percent of GDP was between 4.1 % (2010) and 6.5 % (2009 and 2017). Kosovo saw consecutive levels of FDI in the years 2009-2011 of 7.1 %, 8.4 % and 8.0 % of GDP. These levels have not subsequently been repeated. In the period 2012-2020, inward foreign direct investment has occurred in the range between 2.7 % of GDP in 2014 and 5.3 % in 2013 and 2015. In 2020, FDI was 5.0 % of GDP.

North Macedonia saw a high point of FDI of 5.7 % of GDP in 2018 and a low point of 1.5 % in 2012. For the rest of the period 2009-2020, FDI fell in the range 1.8 % (2017) to 4.6 % of GDP in 2011. In 2019, the most recent year data is available, it was 3.6 %. Turkey had a lower level of FDI than in other candidate countries and potential candidates. One major reason is its larger size, which provides greater opportunities for domestic investment with a lasting interest. The highest level of FDI as a percentage of GDP was 2.2 % in 2015 and the lowest 0.9 % in 2020.

Government deficit and debt

The general government deficit or surplus relative to GDP measures the difference between government expenditure and receipts, relative to the size of the economy. If the deficit is greater than the economy’s growth rate, then the country’s government debt, the stock of past deficits and surpluses, increases relative to the size of the economy. A large debt burden may mean that a large proportion of government receipts are allocated to interest payments. Many governments attempt to run a small deficit or a surplus in good economic periods, while allowing larger deficits in times of recession. The deficit data are illustrated in Figure 5, except for Kosovo for which data is not available, and that for debt in Figure 6. The two figures should be read together.

The European system of national and regional accounts (ESA) provides the methodology for national accounts and government statistics in the EU. Under the terms of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP), EU Member States are required to provide the European Commission with their government deficit and debt statistics before 1 April and 1 October of each year. From October 2014 onwards, candidate countries were asked to report EDP-related data to Eurostat with the same frequency as EU Member States. This reporting was extended to potential candidates as from October 2018.

The trajectory of government deficits over the period 2009 to 2020 (Turkey to 2019; Bosnia and Herzegovina to 2018) in the candidate countries and potential candidates, as well as in the EU, can be divided into three periods. In 2009, the direct effects of the 2007-2008 global financial and economic crisis, which triggered a sharp downturn in public finances globally, can still be observed; for the EU, this continues until 2010. In the period 2010-2019, governments in candidate countries, potential candidates, as well as, the EU from 2011, attempted to control their public deficits with varying degrees of success. By 2019, all candidate countries and potential candidates, from which data is available, and the EU had smaller deficits than in 2009. In the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, this trend led to a government surplus 2015-2018. In 2020, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic had a very clear negative impact on all government deficits.

In 2009 general government deficits in the candidate countries and potential candidates as a percentage of GDP ranged from 2.6 % in North Macedonia to 7.1 % in Albania. For Albania, Turkey and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the deficits in 2009 were the largest of the whole period 2009-2019/2020. The EU’s collective government deficit was 6.0 % of GDP in 2009, as it was also in 2010, its worst outcomes of the period until 2019; however, the COVID-19 crisis resulted in an even higher deficit, at 6.9 % of GDP, in 2020.

Albania, Turkey and Bosnia and Herzegovina had some success in reducing their government deficits in the period 2010 to 2019. The deficit in Bosnia and Herzegovina did not again pass 3 % of GDP and there was a government surplus from 2015 to 2018, the most recent year for which data is available. In 2017, the government surplus reached 2.6 % of GDP. Turkey also reduced its deficit below 3 % of GDP from 2010 to 2018, with a surplus in 2013-2015, reaching 0.5 % of GDP in 2015. In 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, the deficit had widened again to 4.5 % of GDP. Albania’s government deficit stayed above 3 % of GDP during the period 2010-2015, peaking in 2014 at 5.2 %. During the period 2016-2019, deficits were smaller than or equal to 2.0 % of GDP, the smallest being 1.6 % in 2018.

Serbia’s deficit in 2009 had been 4.2 % of GDP in 2009. In subsequent years, the deficit widened, reaching 6.4 % of GDP in 2012 and not falling below 3 % until 2016, when it was 1.2 % of GDP. In 2017 and 2018, Serbia recorded a surplus of 1.1 and 0.6 % of GDP, respectively, and in 2019 a small deficit of 0.2 %. North Macedonia had the smallest deficit in 2009 among the candidate countries and potential candidates at 2.6 % of GDP. The deficit stayed at a similar level in 2010-2011, then deteriorated to greater than 3% of GDP in the years 2012-2015, reaching 4.2 % in 2014. During 2016-2019, the deficit was again below 3% of GDP, the smallest figure being recorded in 2018 at 1.8 %. In 2019, the deficit was 2.0 % of GDP, a slight improvement on 2009. Montenegro had the greatest difficulty among the candidate countries and potential candidates in restraining its government deficit in the period 2010-2018. During this time, the deficit was greater than 3 % of GDP in all years except 2016, when it was 2.8 %. It peaked at 7.3 % in 2015. In 2019, the deficit was 2.0 % of GDP, a considerable improvement on the 2017 figure of 5.7 %; the deficit in Montenegro was also 5.7 % at the beginning of the decade, in 2009.

The EU’s experience was not very different from the candidate countries and potential candidates during this period. The deficit remained at 6.0 % in 2010, only falling marginally below 3 % in 2013. It then remained below this level until 2019, when it was 0.5 % of GDP, near its best of 0.4 % in 2018.

In 2020, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has had a major negative impact on government deficits. Among the candidate countries and potential candidates reporting data, the outcomes fell between a deficit of 10.7 % in Montenegro and one of 6.7 % in Albania. The EU government deficit was 6.9 % of GDP in 2020.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10dd_edpt1) and Eurostat data collection

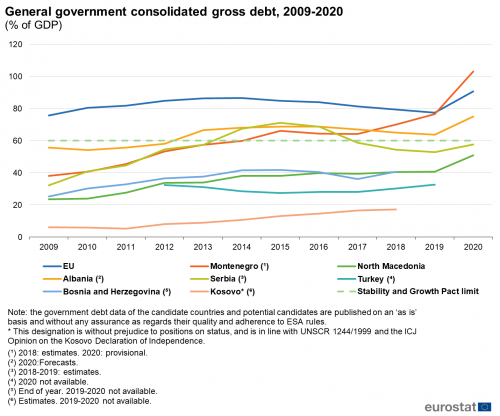

In 2009, following the financial and economic crisis, the ratio of general government debt-to-GDP in those candidate countries and potential candidates which reported data ranged from 23.6 % in North Macedonia to 55.7 % in Albania. Kosovo reported no debt prior to 2009; it was 6.1 % of GDP in that year. The time series available for Turkey covers 2012-2019 and 2009-2018 for Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as Kosovo.

Despite the efforts to reduce government deficits and the occasional surpluses described above, the government debt level in all those candidate countries and potential candidates that reported data for the full 2009-2020 period was higher in 2019 than it had been in 2009. The lowest debt level in 2019 comparable with 2009 was in North Macedonia at 40.7 % of GDP, an increase since 2009 of 17.1 percentage points. The highest debt to GDP ratio in 2019 was 76.5 % in Montenegro, an increase of 38.4 % since 2009. The smallest increase in the debt ratio was in Albania, at 8.1 %, reaching 63.8 % in 2019. Serbia’s government debt was 52.9 % of GDP in 2019, an increase of 20.8 % over 2009. Debt as a percentage of GDP in 2019 was 32.6 % in Turkey, which had not reported in 2009. Thus the candidate countries and potential candidates entered 2020 not having fully countered the effects of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis on general government debt. The impact in that year of the COVID-19 pandemic on government debt resulted in the debt to GDP ratio deteriorating to 103.1 % in Montenegro; 75.1 % in Albania; 57.7 % in Serbia and 51.0 % in North Macedonia.

General government debt across the EU stood at 75.7 % in 2009 and rose to 86.6 % in 2014, before falling to 77.5 % in 2019. The EU was therefore in a similar debt position in 2019 as it had been in 2009. EU debt in 2020 was 90.7 % of GDP.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Data for the enlargement countries are collected for a wide range of indicators each year through a questionnaire that is sent by Eurostat to candidate countries or potential candidates. A network of contacts has been established for updating these questionnaires, generally within the national statistical offices, but potentially including representatives of other data-producing organisations (for example, central banks or government ministries). The statistics shown in this article are made available free-of-charge on Eurostat’s website, together with a wide range of other socio-economic indicators collected as part of this initiative.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available. |

Context

Statistics on prices and finance illustrate the macroeconomic environment, in particular inflation and government and external payments deficits or surpluses, and so provide the framework for government policy decisions. Foreign direct investment statistics provide a measure of the attractiveness of a country as an investment destination. The global financial and economic crisis resulted in serious challenges being posed to many European governments. The main concerns were linked to the ability of national administrations to be able to service their debt repayments, take the necessary action to ensure that their public spending was brought under control, while at the same time trying to promote economic growth.

Within the EU, multilateral economic surveillance was introduced through the stability and growth pact, which provides for the coordination of fiscal policies. Economic and financial statistics have become one of the cornerstones of governance at a global and European level, for example, to analyse national economies during the global financial and economic crisis or to put in place EU initiatives such as the European semester, designed to promote discussions concerning economic and budgetary priorities, or the macroeconomic imbalance procedures (MIP).

While basic principles and institutional frameworks for producing statistics are already in place, the enlargement countries are expected to increase progressively the volume and quality of their data and to transmit these data to Eurostat in the context of the EU enlargement process. EU standards in the field of statistics require the existence of a statistical infrastructure based on principles such as professional independence, impartiality, relevance, confidentiality of individual data and easy access to official statistics; they cover methodology, classifications and standards for production.

Eurostat has the responsibility to ensure that statistical production of the enlargement countries complies with the EU acquis in the field of statistics. To do so, Eurostat supports the national statistical offices and other producers of official statistics through a range of initiatives, such as pilot surveys, training courses, traineeships, study visits, workshops and seminars, and participation in meetings within the European Statistical System (ESS). The ultimate goal is the provision of harmonised, high-quality data that conforms to European and international standards.

Additional information on statistical cooperation with the enlargement countries is provided here.

Notes

* This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

Direct access to

- Statistical books/pocketbooks

- Key figures on enlargement countries — 2019 edition

- Key figures on enlargement countries — 2017 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Leaflets

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2019 edition

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2018 edition

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2016 edition

- Factsheets

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — Factsheets — 2021 edition

- Government finance statistics (EDP and ESA2010) (gov_gfs10)

- Annual government finance statistics (gov_10a)

- Government deficit and debt (gov_10dd)

- HICP (2015 = 100) - annual data (average index and rate of change) (prc_hicp_aind)

- European Union direct investments (bop_fdi)

- European Union direct investments (BPM6) (bop_fdi6)

- Harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) (ESMS metadata file — prc_hicp)

- Balance of payments - International transactions (ESMS metadata file — bop)

- European Union direct investments (BPM6) (ESMS metadata file — bop_fdi6)

- Government deficit and debt (ESMS metadata file — gov_10dd)