Archive:The EU in the world - education and training

- Data extracted in March 2016. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: June 2018.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2016.

The article focuses on education and training statistics in the European Union (EU) and in the 15 non-EU members of the Group of Twenty (G20). It covers a range of subjects, including: educational expenditure, personnel, participation rates and attainment and gives an insight into education in the EU in comparison with the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (educ_figdp) and (educ_uoe_fine06) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

(average number of pupils per teacher)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_perp04) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

(% of total population of pre-primary school age)

Source: Eurostat (tps00179) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS)

(% of the specified population)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_150) and the International Labour Organization (ILOSTAT)

Main statistical findings

Educational expenditure

Public educational expenditure relative to GDP was highest in South Africa at 6.4 %

Public expenditure on education includes spending on schools, universities and other public and private institutions involved in delivering educational services or providing financial support to students. The cost of teaching increases significantly as a child moves through the education system, with expenditure per pupil/student considerably higher in universities than in primary schools. Comparisons between countries relating to levels of public expenditure on education are influenced by differences in price levels and by numbers of pupils and students.

Figure 1 provides information on the level of public expenditure relative to gross domestic product (GDP). Among the G20 members this was highest in 2012 in South Africa at 6.4 %, followed by Brazil at 5.9 %. At the other end of the scale were Japan and India at 3.8 %, Indonesia at 3.4 %, and 2.9 % in Turkey (2006 data). The EU-28, at 5.2 %, ranked among the remaining group of G20 members whose public expenditure on education accounted for 4.2 % to 5.3 % of GDP. Within the last decade there has been an increase in the expenditure committed to education in most G20 countries. Saudi Arabia and the United States were the exceptions: the percentage of GDP spend on education decreased by 2.5 percentage points (pp) in Saudi Arabia (2002 to 2008) and by 0.2 pp in the United States (2002 to 2011). While Brazil, South Africa and Argentina presented an increase in the percentage of GDP invested in education between 2002 and 2012 of over 1.0 pp.

Numbers of teachers and pupils

In general, pupil-teacher ratios were lowest for upper secondary education and highest for primary education

Figure 2 shows the pupil-teacher ratio for primary and secondary education among the G20 members. These ratios are calculated by dividing the number of full-time equivalent pupils and students by the number of full-time equivalent educational personnel. A full-time equivalent is a unit to measure employed persons or students in a way that makes them comparable although they may work or study a different number of hours per week. The unit is obtained by comparing the number of hours worked or studied by a person with the average number of work hours of a full-time worker or student. A full-time person is therefore counted as one unit, while a part-time person gets a score in proportion to the hours they work or study.

In 2013, the average number of pupils per teacher was generally lowest for upper secondary education and highest for primary education, with the main exceptions recorded for members where the ratios were very similar across all three levels of education, such as in Australia, the United States, Canada (2010 data) and Saudi Arabia, and to a lesser extent, Indonesia and Turkey. The largest gaps between primary and secondary pupil-teacher ratios were presented in Mexico (2012 data) and Argentina (2008 data).

In the case of primary education India, South Africa (2011 data) and Mexico had pupil-teacher rates above the world average, while the EU-28 average presented figures below the estimated values for the world. The pupil-teacher ratio was the highest also in India in lower secondary education, followed by Australia and Turkey both with ratios over 20 students per teacher. For upper secondary education the ratio pupil/teacher was 32.1 in India, far above the ratios of Turkey, China and Indonesia that were also above the world average. Overall, India had the highest pupil-teacher ratios, in the three levels of education while Saudi Arabia had the lowest in primary education (10.5) and lower secondary (10.4) and Argentina in upper secondary education (8.0).

Starting school and duration

The earliest starting age for compulsory education among G20 members was four years old in Brazil and Mexico, while the latest was seven years old in Indonesia and South Africa (see Figure 3). Among the EU Member States the starting age varied from four in Luxembourg and Northern Ireland (United Kingdom) to seven in Croatia, Estonia, Finland, Lithuania, Sweden and Romania. The duration of compulsory education in G20 members ranged from eight years in India, to 14 years in Brazil and Mexico, compared to an average of 10 years in the EU-28 (ranging from 8 to 12). As a result the earliest leaving age was around 14 in India and reached 18 in the United States, Turkey, Mexico, Brazil and Argentina, and 16 in the EU-28 (ranging from 14 to 18).

School enrolment

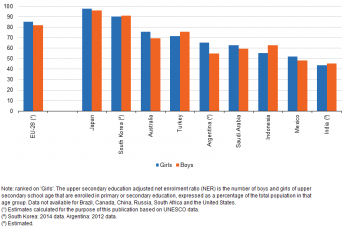

Figures 4 to 7 present enrolment ratios for various education levels. Two types of enrolment ratios are presented, namely ‘net’ and ‘adjusted net’ ratios. Net ratios (shown in Figures 4, 5 and 7 for pre-primary, primary and upper secondary education) compare the number of pupils/students of the appropriate age group enrolled at a particular level of education with the size of the population of the same age group; these ratios cannot exceed 100 %. Adjusted net ratios (shown in Figure 6 for lower secondary education) look at the age group corresponding to a particular level of education and show the share that are in any level of primary or secondary education, in other words including those who are enrolled in levels for which they are formally too young or too old; again these cannot exceed 100 %.

Pre-primary education has increasingly been recognised as having a crucial role in preparing children for the rest of their school lives. More and more educational systems are including early childhood education as compulsory. The EU has set a target of 95 % participation in early childhood education by 2020 (Education and training 2020). This indicator relates to the share of the population which participates in early education among those aged between four years and the age when compulsory education starts. In 2002, the early childhood education rate in the EU-28 was 87.7 % and this rose to 93.9 % by 2012 — the largest share among the available data from the G20 countries (see Figure 4). South Korea, Japan and Mexico presented enrolment ratios above 80 %. For three G20 countries — Indonesia, Turkey and Saudi Arabia — less than half of the early childhood population was enrolled in pre-primary schools, with Saudi Arabia having the lowest rate (10.4 % of boys and 16.7 % of girls).

Figure 4 depicts higher pre-primary enrolment rates for girls than for boys in almost all countries, with only Turkey, Russia and South Korea having higher rates among boys (data by sex is not available for Japan). In Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Mexico, the female enrolment rates were at least 1.5 pp higher than male enrolment rates, with Saudi Arabia presenting the largest gender gap: 6.3 pp higher for girls.

Primary education was effectively universal in Canada and Japan

Moving on from pre-primary education, enrolment in primary education was effectively universal in Canada (1999 data) and Japan for both boys and girls, with ratios of 98 % or higher also recorded for Argentina (2012 data) and the EU-28 (see Figure 5). Among the other G20 members, the primary education net enrolment ratio fell below 93 % in Turkey, the United States, Indonesia, India and South Africa. As for pre-primary education, primary education enrolment ratios for boys and girls were quite similar in all G20 members with the exception of Saudi Arabia (with more boys enrolled) and India (with more girls enrolled).

Figure 6 presents the adjusted net enrolment ratios in 2013 for lower secondary education, which include all lower secondary aged children regardless of the grade they are enrolled in. Japan reported the highest ratios, with close to universal enrolment. Adjusted net enrolment ratios below 80 % for both boys and girls were recorded for lower secondary education in Mexico (2012 data), India, Saudi Arabia and China (2006 data). Regarding the gender gap within the enrolment rates in lower secondary school, only Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Italy presented higher male enrolment rates, while the opposite happened in all the other countries with available data.

In Figure 7 Japan was again in the lead regarding the net enrolment ratios of upper secondary education for both boys and girls, followed closely by South Korea which also presents rates above 90 %. The EU-28 was next in the rank, presenting a total enrolment rate of 83.5 %. On the other hand, in Mexico (boys only) and India less 50 % or less of the upper secondary aged children were enrolled in this level of education. As for the gender gaps, the situation differs from the lower secondary education. In Saudi Arabia there were more girls enrolled than boys (contrary to the situation in lower secondary education). In India the situation in upper secondary was also inverse from the one in lower, with higher enrolment rates for boys in upper secondary. Argentina presented the highest gender gap among the net enrolment rates in upper secondary education: 65.4 % for girls and 55.1 % for boys in 2012.

The United States and Russia had the highest rates for secondary educational attainment

Figure 8 shows the percentage of population aged 25 years and over having completed upper secondary education in 2014. In the United States, Russia (2010 data) and Canada (2011 data) the share was over 80 % for both the male and female populations. In Indonesia, Mexico and China (2010 data), the upper secondary attainment rates were under 35 %.

The Unites States, the EU-28 and Brazil formed a group of countries were the share of men aged 25 or over having completed upper secondary education was higher than the share of women obtaining that degree. In all other countries where data was available the female shares were higher, and the largest gaps were in Turkey and South Korea (2010 data), both presenting a difference of over 13 pp.

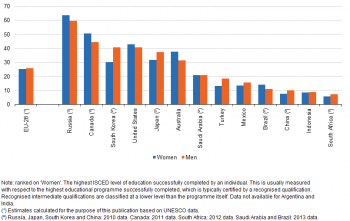

Tertiary education is generally provided by universities and other higher education institutions. In 2014, slightly over one quarter of the EU-28 adult population (aged 25 and over) had obtained a degree in tertiary education (25.3 % for women and 25.9 % for men). Russia (2010 data), presented a 63.7 % share for women and a 59.7 % share for men, and along with five other G20 member, reported ratios for tertiary education attainment over 30.0 % (see Figure 9). The lowest tertiary educational attainment levels were found in Indonesia and South Africa (2012 data) with shares below 10.0 % in both countries for women and men.

The largest gender gaps in favour of women were reported by Canada and Australia, while more countries reported gender gaps in favour of men, out of which South Korea, Japan (2010 data) and Turkey presented differences in the range of 10.7 pp to 5.3 pp.

Not in employment, education or training

Japan and Australia had the lowest proportion of young people not in employment, education or training

Traditional analyses of the labour market focus on employment and unemployment, but for younger people many are still in education. Labour market policies for young people often focus on those who are not in employment, education or training, abbreviated as NEETs. Factors that affect the proportion of young people not in employment, education or training include the length of compulsory education, types of available educational programmes, access to tertiary education, as well as labour market factors related to unemployment and economic inactivity (being neither employed nor unemployed). Figure 10 indicates the proportion of 15–24 year olds that were not enrolled in education (school or formal training) nor employed in 2014. Among the G20 members with available data this ranged from 5 % or less in Australia (2010 data) and Japan, through 12 % for Russia and 13 % for the EU-28 to 24 % in Indonesia, 25 % in Turkey, and 31 % in South Africa. With the exception of Australia, where the NEET ratio was higher for men, all other countries reported higher rates among women. The gender gap within the NEETs was far larger than in the case of the previous indicators on enrolment, with Mexico and Saudi Arabia having presented the female rates more than three times as high as the male rates.

Data sources and availability

The statistical data in this article were extracted during March 2016.

The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes global — standards. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU data

Most if not all of the indicators presented for the EU have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this article and data that is subsequently downloaded. In exceptional cases, such as the data for enrolment rates and youth literacy rates, some indicators for the EU have been extracted from international sources.

G20 members from the rest of the world

For the 15 non-EU G20 members, the data presented have been extracted from a range of international sources, namely the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, the United Nations Statistics Division and the International Labour Organization. For some of the indicators shown a range of international statistical sources are available, each with their own policies and practices concerning data management (for example, concerning data validation, correction of errors, estimation of missing data, and frequency of updating). In general, attempts have been made to use only one source for each indicator in order to provide a comparable analysis between the members.

Context

Education and training help foster economic growth, enhance productivity, contribute to people’s personal and social development, and reduce social inequalities. In this light, education and training has the potential to play a vital role in both an economic and social context. Education statistics cover a range of subjects, including: expenditure, personnel, participation rates and attainment. The standards for international statistics on education are set by three international organisations: the Institute for Statistics of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation; the OECD; and Eurostat.

The classification used to distinguish different levels of education is the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). The version used in this publication is ISCED 1997 which has seven levels of education.

- Level 0 pre-primary education — for children aged at least three years.

- Level 1 primary education — begins between five and seven years of age.

- Level 2 lower secondary education — usually, the end of this level coincides with the end of compulsory education.

- Level 3 upper secondary education — entrance age is typically 15 or 16 years.

- Level 4 post-secondary non-tertiary education — between upper secondary and tertiary education; serves to broaden the knowledge of level 3 graduates.

- Levels 5 and 6 first and second stages of tertiary education — includes programmes with academic and occupational orientations as well as those that lead to an advanced research qualification.

As from 2014 onward, the new ISCED 2011 version of the classification is used in the European Union and some of the G20 countries but not all. However the aggregated levels used here are not affected by the changes which occurred in more detailed subcategories.

See also

- All articles on the non-EU countries

- Educational expenditure statistics

- Other articles from The EU in the world

- Early leavers from education and training

- Tertiary education statistics

- International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED)

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- More and more persons aged 30 to 34 with tertiary educational attainment in the EU Press release April 2016

- The EU in the world 2016

- The European Union and the African Union — 2014 edition

- Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) — A statistical portrait — 2016 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Pocketbook on Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2013 edition

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

- Key data on education in Europe 2012

Main tables

- Education (t_educ)

- Education indicators - non-finance (t_educ_indic)

- Participation in early childhood education (tps00179)

- Education indicators - non-finance (t_educ_indic)

Database

- Education (educ)

- Education indicators - non-finance (educ_indic)

- Pupil/Student - teacher ratio and average class size (ISCED 1-3) (educ_iste)

- Indicators on education finance (educ_finance)

- Expenditure on education as % of GDP or public expenditure (educ_figdp)

- Expenditure on public educational institutions (educ_fipubin)

- Enrolments, graduates, entrants, personnel and language learning - absolute numbers (educ_isced97)

- Students by ISCED level, age and sex (educ_enrl1tl)

- Education indicators - non-finance (educ_indic)

- Youth (yth), see:

- Youth employment (yth_empl)

- Young people not in employment and not in any education and training by sex, age and activity status (yth_empl_150)

Dedicated section

- Education and training

- Employment and social policy see Youth indicators

- Youth

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/youth/overview

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

![]() Education and training: tables and figures

Education and training: tables and figures

External links

- International Labour Organization ILO

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO

- United Nations Statistics Division

- World Bank