Archive:Enlargement countries - finance statistics

Data from April 2022.

Planned article update: May 2023.

Highlights

Three of the EU candidate countries and potential candidates — Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia — recorded government budget deficits every year between 2010 and 2021 or the most recent year for which data is available.

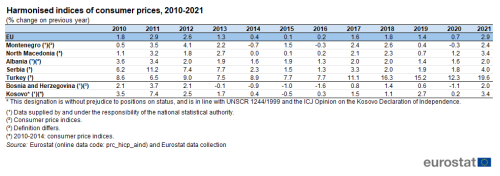

Between 2014 and 2021, the highest annual consumer price increases among the EU candidate countries and potential candidates were recorded in Turkey, at 19.6 %.

Harmonised indices of consumer prices, 2010-2021

This article is part of an online publication and provides information on a range of financial statistics for the European Union (EU) candidate countries and potential candidates, in other words the enlargement countries. Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Turkey currently have candidate status, while Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as Kosovo* are potential candidates.

The article provides information on price and finance statistics, covering consumer price indices; interest rates; foreign exchange rates; the balance of payments, including foreign direct investment (FDI); and government finance: the general government deficit/surplus and government debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP).

Full article

Consumer prices

A consumer price index measures changes in the prices of a representative set of goods and services consumed by households. It is an important measure of inflation. In the European Union, the harmonised index of consumer prices provides a consumer price index that is directly comparable between countries.

Annual percentage changes in the Harmonised index of consumer prices and in national consumer price indices are shown in Table 1 and in the graph in the Highlights section above.

(% change on previous year)

Source: Eurostat (prc_hicp_aind) and Eurostat data collection

Consumer prices in most of the candidate countries and potential candidates generally increased more in the period 2010-2012 than in the period 2014-2020, with 2013 representing a transition year. Consumer price rises in Serbia, during the period 2010-2013, in Turkey, during the whole period 2010-2021, and in Kosovo in 2011, were higher than those recorded across the other candidate countries and potential candidates, as well as in the EU. While there does not seem to be any discernible effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer price changes in 2020, price increases in 2021 across the region were higher than in any year since at least 2014, except in Albania and Montenegro.

In Serbia, consumer price inflation was higher during the period 2010-2013 than subsequently. Serbia’s inflation high point during the 2010-2021 period was in 2011 at 11.2 % and its low point in 2016 at 1.3 %. During the period 2014-2020, the highest consumer price rise recorded for Serbia was 3.3 % in 2017. In 2021, consumer prices rose by 4.0 %.

In Turkey, peak consumer price inflation occurred in 2021, at 19.6 %. Prior to this, the highest point had been in 2018, when prices increased by 16.3 %. In 2018, price increases in the other candidate countries and potential candidates were around the average for the whole period and were lower than they had been during 2010-2013. Turkish consumer price inflation has moved higher during the period 2017-2021. The lowest annual consumer price increase during the whole period 2010-2021 was recorded in 2011, at 6.5 %.

Albania’s consumer price increase high point over the period 2010-2021 was 3.6 % in 2010 and the low point 1.3 % in 2016, representing a fairly narrow range. The years 2010 and 2011, in which the consumer price index rose by 3.6 % and 3.4 %, respectively, can be seen as deviating from the subsequent period. After 2011, the highest annual increases of consumer prices, by 2.0 %, were recorded in each of the years 2012, 2017, 2018 and 2021.

Bosnia and Herzegovina had a pattern of consumer price changes over the period 2010-2021 that was somewhat similar to that in Albania. The largest annual consumer price increase, at 3.7 %, occurred in 2011; the next largest, 2.1 %, in both 2010 and 2012. Subsequently and until 2020, price changes lay between -1.6 %, occurring in 2016, and 1.4 %, in 2018. In 2021, consumer prices increased by 2.0 %.

Kosovo also had higher inflation in the period 2010-2012, peaking at 7.4 % in 2011. In the period 2013-2020, changes in the consumer price level were mostly within the narrow range from -0.5 % in 2015 to 1.7 % in 2013. An exception occurred in 2019, when the change was 2.7 %. In 2021, consumer prices rose by 3.4 %.

Consumer prices in Montenegro from 2013 to 2021 have changed by between -0.7 %, in 2014 and 2.6 %, in 2018. During the earlier period 2010-2012, consumer price rises in Montenegro were generally higher, although they rose by only 0.5 % in 2010. The largest increase was in 2012 at 4.1 %. In 2021, consumer prices rose by 2.4 %.

North Macedonia has had rather stable consumer prices, with the low for the period 2010-2021 occurring in 2014 at 0.0 % and the high in 2021, at 3.4 %. The second highest increase in this period occurred in 2011 when consumer price rose by 3.2 %.

Increases in the all-items harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) remained at low levels across the EU over the period 2010-2021. The low of 0.1 % occurred in 2015 and the high of 2.9 % was recorded in both the years 2011 and 2021. EU price changes shown cover all 27 Member States. These can be compared to a limited extent with the European Central Bank inflation targets for the Euro area or Eurozone, which since 2015 has comprised 19 Member States. Prior to July 2021, the target was below, but close to, 2 % a year. Currently, the ECB aims for a ‘symmetric 2 % inflation target over the medium term [1].

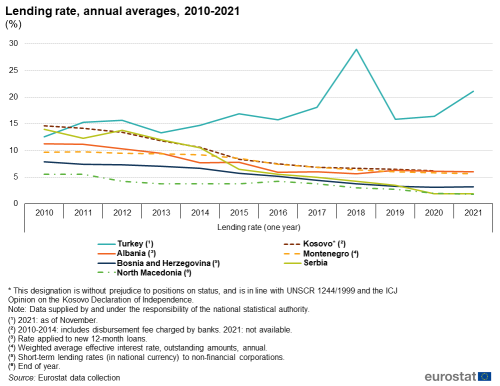

Interest rates

An interest rate is the cost of borrowing or the gain from lending, usually expressed as an annual average percentage amount. The central bank interest rate is the official rate at which the European Central Bank and national central banks lend money to commercial banks for very short periods. This rate is an instrument for influencing interest rates in the economy and inflation. Interest and inflation rates are therefore closely linked. Countries can manage their interest rates either to target inflation or currency exchange rates.

The lending rate, illustrated in Figure 1, is the interest rate charged in the wholesale ‘money market’ for loans or transactions in liquid (easily marketable) financial securities of maximum one year’s duration. This provides the ceiling on money market interest rates. In countries where the financial markets are less developed, the lending rate is the interest rate charged by central banks to commercial banks for short term funding against marketable financial securities. The lending rate is higher than both the deposit rate and the central bank interest rate. Bank loans to large low-risk companies are at an interest rate linked to but higher than the lending rate. Bank lending to clients that are perceived as greater risks normally entail still higher interest rates.

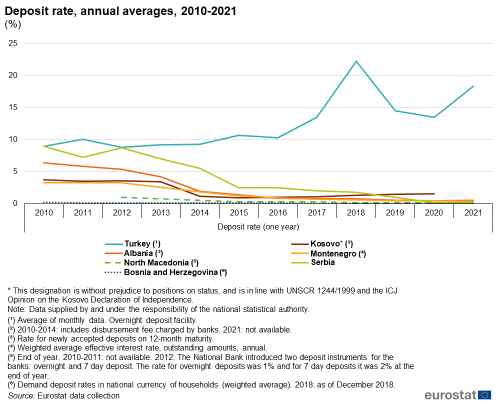

The deposit rate, as illustrated in Figure 2, is the annualised interest rate which the central bank pays on short-term deposits by banks or pays for short-term liquid financial instruments (bills). It is below the interest rate which banks can obtain on the money market and so forms the floor for money market interest rates. The deposit rate is closely related to the official bank rate.

The lending rate declined between 2010 and 2021 in most of the candidate countries and potential candidates under the influence of the recovery from the 2008 global financial crisis, the subsequent reduction in inflation from 2013-2020 and continuing loose monetary policy within the EU.

Turkey was clearly an outlier over the period 2010-2021, with an average lending rate of 17.1 %; a maximum of 29.0 % in 2018, long after other candidate countries and potential candidates had passed their peak; and a minimum of 12.6 % in 2010. Its average, maximum and minimum rates were all the highest in the region. Turkey’s lending rate in 2021 was 21.1 %. Kosovo’s average lending rate over the period 2010-2020 was 9.7 %; its highest rate was 14.6 % in 2010 and its lowest 6.2 % in 2020. There is no data available for 2021.

Serbia (7.6 %), Albania and Montenegro (7.8 % each), had similar average lending rates over the period 2010-2021. Serbia’s maximum lending rate was 14.0 % in 2010; its minimum was 1.9 % in both years 2020 and 2021. Albania’s maximum rate was 11.3 % in 2010, its minimum 5.7 % in 2018 and its most recent 6.0 % in 2021. Montenegro’s maximum lending rate was 9.7 % in 2011 and its minimum was 5.7 % in 2021.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s average lending rate over 2010-2021 was 5.4 %, its maximum was 7.9 % in 2010 and its minimum 3.1 % in 2020. In 2021, its lending rate was 3.2 %. North Macedonia’s average lending rate over the period 2010-2021 was 3.7 %, its maximum 5.5 % in both years 2010 and 2011 and its minimum 1.8 % in 2021.

A decline in the deposit rate in most of the candidate countries and potential candidates can be observed that is similar to the decline in the lending rate. Deposit rates fell below 1 % in Montenegro from 2016; in North Macedonia from 2013; in Albania from 2016; in Serbia from 2020; in Bosnia and Herzegovina, throughout the period; and in Kosovo only in 2015, while after 2015 the rates increase year by year, to 1.5 % in 2020 (latest available data). Turkey is again an outlier: its minimum deposit rate was recorded in 2012 at 8.8 %. Between 2010 and 2021, the difference between deposit and lending rates narrowed throughout the region except in Albania. The most significant declines occurred in Kosovo (between 2010-2020), Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia.

As shown in the footnotes of Figure 2, comparisons are difficult between deposit rates in candidate countries and potential candidates. Nevertheless, the deposit rate in Turkey in 2021, at 18.4 %, was 5.9 percentage points (pp) above its average for the period (12.5 %) and higher than elsewhere in the region. In Kosovo, the deposit rate in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available, was 1.5 %. Elsewhere, as stated above, it was below 1 %.

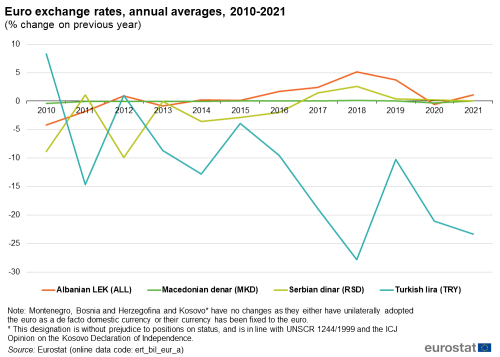

Exchange rates

One currency is exchanged for another at foreign exchange rates. Montenegro and Kosovo have unilaterally adopted the euro as their de facto currency. Bosnia and Herzegovina has fixed its currency to the euro, so that there has been no change in the exchange rate over the period 2010-2021. Annual average changes in the exchange rates against the Euro for those candidate countries that have floating currencies, Albania, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey, are shown in Figure 3. Annual appreciation of the foreign currency against the Euro is shown as a positive percentage figure, depreciation as a negative figure.

(% change on previous year)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a)

The Albanian lek depreciated against the euro by 4.2 % in 2010 and by a further 1.8 % in the following year. It then appreciated during the period 2014-2019, notably by 5.1 % in 2018. Over the period 2010-2021, the lek had appreciated by 12.5 % against the euro.

Although there is no official North Macedonia exchange rate target, its currency, the denar, maintained a near-stable exchange rate with the euro over the period 2010 to 2021 (overall depreciation of only 0.2 %). In 2010, 2013, 2014 and 2020 there were small depreciations against the euro (ranging between -0.4 and -0.1 %), while in 2018 and 2021 there were small appreciations of 0.1 %; in all other years the changes were 0.0 % (values rounded to one decimal).

The Serbian dinar depreciated against the euro by 8.8 % in 2010 and by 9.9 % in 2012. Smaller depreciations continued in 2014-2016, of which the maximum was 3.6 % in 2014, followed by a modest appreciation over 2017-2020. Serbia’s exchange rate was stable against the euro in 2021. Over the period 2010-2021, the dinar has depreciated against the euro by 12.4 %.

Although the Turkish lira appreciated by 8.3 % in 2010 and again by 1.1 % in 2012, it has depreciated in every other year in the period in question, most notably by 27.8 % in 2018. Total depreciation against the euro over 2010-2021 was 81.0 %.

Balance of payments

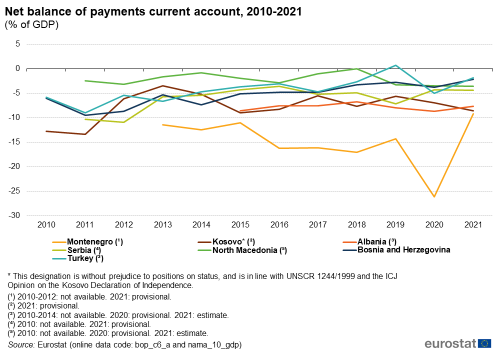

The current account of the balance of payments represents transactions with the rest of the world concerning merchandise, services, income and other current transfers. It is normal for countries that are very fast growing to run negative balances, which represent borrowing from the rest of the world. Developed countries often run surpluses, which represent building up assets in the rest of the world. A balance of payments deficit that is large compared with the country’s nominal GDP growth can lead to financial difficulties. Data for the candidate countries and potential candidates is illustrated by Figure 4.

Data for Montenegro is available for 2013-2021. The payments deficit in 2013 was -11.4 % of GDP. Since then, there was an almost continual deterioration in the payments deficit to 2020, with slight improvements in 2015, at a payments deficit of -11.0 %, and in 2019 at a payments deficit of -14.3 %. The 2020 deficit was -26.1 % of GDP. The 2021 provisional figure was an improved balance of payments deficit equal to -9.2 % of GDP.

High payments deficits were recorded in Kosovo in 2010 at -12.8 % of GDP and 2011, at -13.4 %, the largest over the period 2010-2021. During 2012-2014, the payments deficits diminished, the largest being in 2012 at -6.1 % and the smallest in 2013 at -3.5 % of GDP. With the exceptions of 2017 and 2019, when the payments deficits were -5.5 % and -5.7 %, respectively, the deficit between 2015 and 2021 has ranged between -9.0 % in 2015 and -7.0 % in 2020. The 2021 payments deficit was -8.6 % of GDP.

Albanian data is available for 2015-2021. The largest balance of payments deficit was in 2020, at -8.7 % of GDP; and the smallest in 2018 at -6.7 %. The 2021 deficit was -7.7 % of GDP.

Serbian data is available from 2011 to 2021. In 2011 and 2012, the payments deficit was -10.3 % and -10.9 %, respectively, of GDP. Since then, the largest payments deficit was recorded in 2019, at -7.1 %; and the smallest in 2016 at -3.6 % of GDP. The 2021 observation was a deficit of -4.4 % of GDP.

Data from North Macedonia is also available from 2011 to 2021. Before 2019, its deficit exceeded -3 % of GDP on only one occasion, in 2012, at -3.2 %. Since 2019, the deficit has been consistently somewhat over -3 %; in 2021 it was -3.5 %.

Data for Bosnia and Herzegovina is available for 2010 to 2021. The largest payments deficit was in 2011, at -9.5 % of GDP; and the smallest, in 2019, was -2.8 %. 2012 saw the second largest payments deficit at -8.6 % of GDP. Thereafter, payments deficits mostly diminished to the range between -2.8 % in 2019 to -5.3 % in 2013, although the 2014 payments deficit figure was -7.3 %. The 2021 deficit was -2.1 % of GDP.

In Turkey, data is available from 2010. Other than in 2011, when the payments deficit was -9.0 % of GDP, and 2019, when there was a payments surplus of 0.7 %, the payments deficit ranged between -6.7 % in 2013 and -1.8 % in 2021.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_c6_a) and (nama_10_gdp)

Foreign direct investment

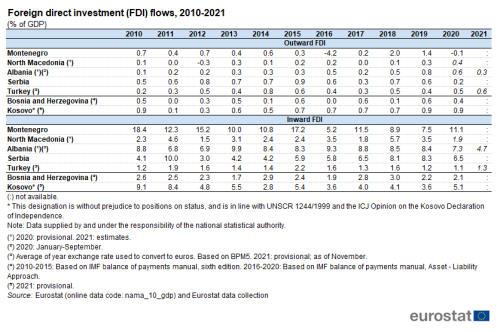

Foreign direct investment (FDI) represents a lasting interest in an enterprise operating in another economy and implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the recipient enterprise. It forms a part of the financial account of the balance of payments. Inflows represent investment in the economy; outflows represent investment by the economy in the rest of the world. Negative values represent disinvestment, which occurs when previous investments are withdrawn from the foreign enterprises; or funds flowing back from the foreign company to the parent; or negative reinvested earnings. Countries that attract considerable inward investment are often themselves investors in other countries.

Table 2 shows outward and inward inflows of foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP for the candidate countries and potential candidates for the period 2010-2021. Each of the candidate countries and potential candidates for which data are available had a higher level of FDI inflows than outflows in every year of the period covered.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp) and Eurostat data collection

Montenegro had the largest average of inward foreign direct investment of the candidate countries and potential candidates as a percentage of its GDP. In 2010, inward FDI was equivalent to 18.4 % of its GDP. Thereafter, inward FDI almost continually diminished to 7.5 % of GDP in 2019, although the outcome in 2015 was 17.2 % of GDP and in 2017, 11.5 %. In 2020, the most recent year for which data was available, inward FDI was equivalent to 11.1 % of GDP. The next largest attractor of foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP was Albania. From 2010 to 2020, inward FDI accounted for between 6.8 % of GDP, in 2011, and 9.9 % in 2013. The 2021 estimated figure was below this range, at 4.7 % of GDP.

Serbia saw a peak of inward FDI in 2011 at 10.0 % of GDP. In 2018 it was at 8.1 % and in 2019, 8.3 % of GDP. 2012 was a low year for FDI at 3.0 % of GDP. In other years, inward foreign direct investment as a percent of GDP ranged between 4.1 % in 2010, and 6.5 % in both 2017 and 2020. This is the most recent year for which data is available. Kosovo saw levels of FDI in the years 2010 and 2011 of 9.1 % and 8.4 % of GDP. These levels have not subsequently been repeated. In the period 2012-2021, inward foreign direct investment has occurred in the range between 2.8 % of GDP in 2014 and 5.5 % in 2013. In 2020, the most recent year for which data is available, FDI was 5.1 % of GDP.

North Macedonia saw a high point of FDI of 5.7 % of GDP in 2018 and a low point of 1.5 % in 2012. For the rest of the period 2010-2021, FDI fell in the range 1.8 %, in 2017, to 4.6 % of GDP in 2011. In 2020, the most recent year data is available, inward FDI was 1.9 % of GDP. Turkey had a lower level of FDI than in other candidate countries and potential candidates. One major reason is its larger size, which provides greater opportunities for domestic investment with a lasting interest. The highest level of inward FDI as a percentage of GDP was 2.2 % in 2015 and the lowest 1.1 % in 2020. The 2021 provisional value of inward FDI was 1.3 % of GDP.

Outward FDI accounts for a very small percentage of GDP in all the candidate countries and potential candidates. Worth noting was Serbia’s outward FDI of 0.9 % of GDP in 2015 and Kosovo’s similar 0.9 % of GDP in 2010, 2019 and 2020. Montenegro had a very large negative outward investment in 2016 of -4.2 % of GDP, representing a repatriation of investment funds.

Government deficit and debt

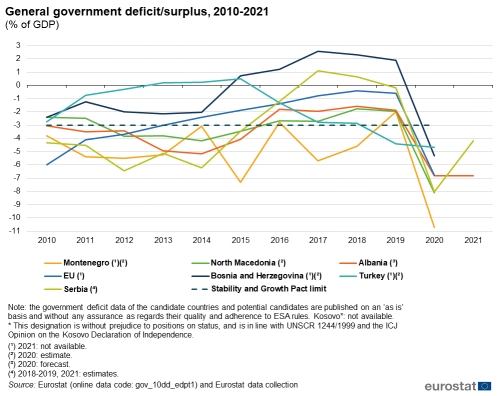

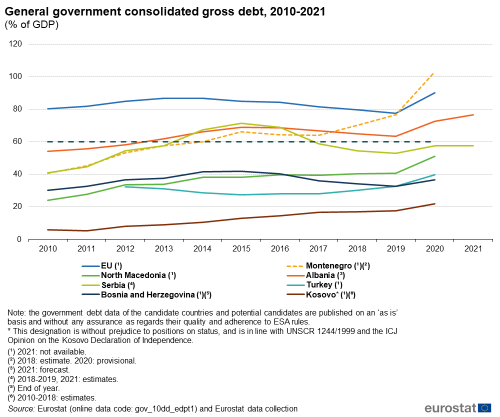

The general government deficit or surplus measures the difference between government expenditure and receipts, relative to the size of the economy and presented as a percentage of GDP. If the deficit is greater in magnitude than the economy’s nominal GDP growth rate, then the country’s government debt, the stock of past deficits and surpluses, increases relative to the size of the economy. A large debt burden may mean that a major proportion of government receipts are allocated to interest payments. Many governments attempt to run a small deficit or a surplus in good economic periods, while allowing larger deficits in times of recession. The deficit data are illustrated in Figure 5, except for Kosovo for which data is not available, and that for debt in Figure 6. The two figures should be read together.

The European system of national and regional accounts (ESA) provides the methodology for national accounts and government finance statistics in the EU. Under the terms of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP), EU Member States are required to provide the European Commission with their government deficit and debt statistics before 1 April and 1 October of each year. From October 2014 onwards, candidate countries were asked to report EDP-related data to Eurostat with the same frequency as EU Member States. This reporting was extended to potential candidates as from October 2018.

The trajectory of government deficits in the candidate countries and potential candidates over the period 2010 to 2021 (data to 2021 for Albania and Serbia, otherwise to 2020) can be divided into two periods. In the period 2010-2019, following the 2007-2008 global financial and economic crisis, governments in candidate countries and potential candidates attempted to control their public deficits with varying degrees of success. By 2019, all candidate countries and potential candidates except Turkey had smaller deficits than in 2010. In the years 2020 and 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic had a very clear negative impact on most government deficits, again excluding Turkey.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10dd_edpt1) and Eurostat data collection

In 2010, general government deficits in the candidate countries and potential candidates as a percentage of GDP ranged from -2.4 % in North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to -4.3 % in Serbia. For Bosnia and Herzegovina, the deficit in 2010 was the largest of the period 2010-2019.

Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and to a lesser extent Turkey, had some success in reducing their government deficits in the period 2010 to 2019. Serbia’s deficit had been -4.3 % of GDP in 2010. In the period 2011-2014, the deficit remained high, reaching -6.4 % of GDP in 2012 and -6.2 % in 2014. From 2015 to 2018, the results improved considerably so that Serbia recorded a surplus of 1.1 % of GDP in 2017, while in 2019 there was a small deficit of -0.2 %. The deficit in Bosnia and Herzegovina did not pass -3 % of GDP and there was a government surplus from 2015 to 2019. In 2017, the government surplus reached 2.6 % of GDP. Turkey also reduced its deficit to less than -3 % of GDP from 2010 to 2018, with a surplus in 2013-2015, reaching 0.5 % of GDP in 2015. In 2019 the deficit had widened again to -4.4 % of GDP.

Albania’s government deficit remained larger than -3 % of GDP over the period 2010-2015, reaching its greatest magnitude in 2014 at -5.2 %. During the period 2016-2019, deficits were less than or equal to -2.0 % of GDP, the smallest being -1.6 % in 2018. North Macedonia’s deficit stayed at a similar level in 2011 as the year before, at -2.4 %. It then deteriorated to greater than -3 % of GDP in the years 2012-2015, reaching -4.2 % in 2014. During 2016-2019, the deficit improved to less than -3 % of GDP, the smallest figure being recorded in 2018 at -1.8 %. Montenegro had the greatest difficulty among the candidate countries and potential candidates in restraining its government deficit in the period 2010-2019. During this time, the deficit was greater than -3 % of GDP in all years except 2016, when it was -2.8 %. It reached its greatest magnitude at -7.3 % in 2015.

Compared with 2019, in 2020, government deficits greatly deteriorated in all candidate countries and potential candidates as a consequence of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The exception was Turkey, where the 2020 deficit widened only marginally from -4.4 % to -4.7 % of GDP. The 2020 outcomes fell between a deficit of -10.7 % of GDP in Montenegro and one of -4.7 % in Turkey. The limited data for 2021 shows that Serbia reduced the deficit to -4.2 % of GDP, while in Albania the deficit remained at the same level as in the previous year (-6.8 % of GDP).

The EU’s government finance experience was not very different from the candidate countries and potential candidates during this period. The deficit was at -6.0 % of GDP in 2010 and remained greater or equal to -3 % of GDP until 2013. It then remained smaller than this level until 2019, when it was -0.6 % of GDP, near its best of -0.4 % in 2018. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in its largest magnitude deficit of the whole period in 2020, at -6.8 % of GDP.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10dd_edpt1) and Eurostat data collection

In 2010, following the financial and economic crisis, the ratio of general government debt-to-GDP in those candidate countries and potential candidates which reported data ranged from 5.9 % in Kosovo to 54.0 % in Albania. The time series available for Turkey covers 2012-2020. Data is available for candidate countries and potential candidates to 2020, except for Albania and Serbia, which have data available to 2021.

Government debt levels in most candidate countries and potential candidates were higher in 2019 than they had been in 2010. Turkey’s debt remained relatively stable from the start of data availability in 2012 to 2019. The lowest debt level in the region in 2019 was in Kosovo at 17.5 % of GDP, an increase from 2010 of 11.6 percentage points. The highest debt to GDP ratio in 2019 was 76.5 % in Montenegro, an increase of 35.9 percentage points since 2010, the greatest in the region. The smallest increase in the debt ratio over 2010-2019 was in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the difference was only 2.5 percentage points, the debt level being 32.7 % of GDP in 2019. Serbia’s government debt was an estimated 52.9 % of GDP in 2019, an increase of 12.1 percentage points over 2010. Debt as a percentage of GDP in Turkey in 2019 was 32.7 % of GDP, having been 32.4 % in 2012. Thus, the candidate countries and potential candidates entered 2020 mostly not having fully countered the effects of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis on general government debt. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on government debt resulted in the debt to GDP ratio deteriorating to 103.1 % in Montenegro in 2020; 76.7 % in Albania in 2021; 57.5 % in Serbia in 2021, 51.2 % in North Macedonia in 2020, 39.8 % in Turkey in 2020, 36.6 % in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2020 and 21.8 % in Kosovo in 2020.

General government debt across the EU stood at 80.4 % of GDP in 2010 and deteriorated to 86.8 % in 2014, before decreasing to 77.5 % of GDP in 2019. The EU was therefore in a slightly improved debt position in 2019 than it had been in 2010. EU debt in 2020 was 90.1 % of GDP.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The enlargement countries are not at the same level of development and are progressing towards an efficient and modern statistical system at different speeds. In a number of areas, candidate countries (and sometimes also potential candidates) are in a position to provide harmonised data in accordance with the EU acquis with respect to methodology, classifications and procedures for data collection and the principles of official statistics as laid down in the European statistics Code of Practice. In these cases, the candidate countries (and potential candidates) concerned report their data to Eurostat following the same procedures and under the same quality criteria as the EU Member States and the EFTA countries. Data from the enlargement countries that meet these quality requirements are published along with data for EU Member States and EFTA countries.

In addition, the enlargement countries provide data for a wide range of indicators for which they do not yet fully adhere to the quality requirements specified in the EU acquis and the methodology, classifications and procedures for data collection specified in the relevant Regulations, Directives and other legal documents. These data are collected on an annual basis through a questionnaire sent by Eurostat to the candidate countries or potential candidates. A network of contacts has been established for updating these questionnaires, generally within the national statistical offices, but potentially including representatives of other data-producing organisations (for example, central banks or government ministries). This annual exercise also provides an opportunity to provide methodological recommendations to the enlargement countries.

The European system of national and regional accounts (ESA) provides the methodology for national accounts in the EU. Data for the EU and the candidate countries and potential candidates were compiled under ESA 2010, which is consistent with worldwide guidelines for national accounts, namely, the United Nations’ system of national accounts (the 2008 SNA).

The HICP data are calculated by the national statistical institutes and reported to the corresponding production unit in Eurostat. Data is available for the EU and the European Economic Area (EEA), as well as for some candidate countries (North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey).

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available. |

Context

Statistics on prices and finance illustrate the macroeconomic environment, in particular inflation and government and external payments deficits or surpluses, and so provide the framework for government policy decisions. Foreign direct investment statistics provide a measure of the attractiveness of a country as an investment destination. The global financial and economic crisis resulted in serious challenges being posed to many European governments. The main concerns were linked to the ability of national administrations to be able to service their debt repayments, take the necessary action to ensure that their public spending was brought under control, while at the same time trying to promote economic growth.

Within the EU, multilateral economic surveillance was introduced through the stability and growth pact, which provides for the coordination of fiscal policies. Economic and financial statistics have become one of the cornerstones of governance at a global and European level, for example, to analyse national economies during the global financial and economic crisis or to put in place EU initiatives such as the European semester, designed to promote discussions concerning economic and budgetary priorities, or the macroeconomic imbalance procedures (MIP).

Information concerning the current statistical legislation on Harmonised Indices of Consumer Prices (HICP), Balance of Payments (BoP), government finance and EDP statistics can be found here:

- Harmonised Indices of Consumer Prices (HICP)

- Balance of Payments (BoP)

- Government finance statistics and EDP statistics

While basic principles and institutional frameworks for producing statistics are already in place, the enlargement countries are expected to increase progressively the volume and quality of their data and to transmit these data to Eurostat in the context of the EU enlargement process. EU standards in the field of statistics require the existence of a statistical infrastructure based on principles such as professional independence, impartiality, relevance, confidentiality of individual data and easy access to official statistics; they cover methodology, classifications and standards for production.

Eurostat has the responsibility to ensure that statistical production of the enlargement countries complies with the EU acquis in the field of statistics. To do so, Eurostat supports the national statistical offices and other producers of official statistics through a range of initiatives, such as pilot surveys, training courses, traineeships, study visits, workshops and seminars, and participation in meetings within the European Statistical System (ESS). The ultimate goal is the provision of harmonised, high-quality data that conforms to European and international standards.

Additional information on statistical cooperation with the enlargement countries is provided here.

Notes

* This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

- ↑ ECB’s Governing Council approves its new monetary policy strategy

Direct access to

- Statistical books/pocketbooks

- Key figures on enlargement countries — 2019 edition

- Key figures on enlargement countries — 2017 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Factsheets

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — Factsheets — 2021 edition

- Leaflets

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2019 edition

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2018 edition

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2016 edition

- Government finance statistics (EDP and ESA2010) (gov_gfs10)

- Government deficit and debt (gov_10dd)

- HICP (2015 = 100) - annual data (average index and rate of change) (prc_hicp_aind)

- European Union direct investments (bop_fdi)

- Balance of payments by country - annual data (BPM6) (bop_c6_a)

- Exchange rates (ert), see:

- Bilateral exchange rates (ert_bil)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates (ert_bil_eur)

- Harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) (ESMS metadata file — prc_hicp)

- Balance of payments - International transactions (ESMS metadata file — bop)

- European Union direct investments (BPM6) (ESMS metadata file — bop_fdi6)

- Government deficit and debt (ESMS metadata file — gov_10dd)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates (ESMS metadata file — ert_bil_eur)