Archive:Employment statistics

Data from May 2019. Planned article update: May 2020

Highlights

The EU-28 employment rate for persons aged 20 to 64 recorded its highest rate in 2018; it stood at 73.1 %.

Even if the employment gap continues to reduce, the employment rate was still higher for men than for women in 2018 in all EU Member States.

In the EU-28, 30.8 % of the employed women aged 20-64 worked on a part-time basis in 2018, while the corresponding share for men is only 8.0 %.

- Tool 1: Employment (total, female, male, youth and senior), 2002-2018

(% of the population aged 20 to 64)

Source: Eurostat

- Tool 1: Employment (total, female, male, youth and senior), 2002-2018

This article presents the most recent European Union (EU) employment statistics based on the EU Labour Force Survey (LFS), including an overview based on socio-economic dimensions. Overall, employment statistics show considerable differences by sex, age and educational attainment level. There are also considerable labour market disparities across EU Member States.

Labour market statistics are at the heart of many EU policies following the introduction of an employment chapter into the Amsterdam Treaty in 1997. The employment rate, in other words the proportion of the working age population in employment, is considered to be a key social indicator when studying developments within the labour market.

Please take note that numbers and rates shown in the tools and mentioned in the text of this article may differ in some cases, due to continuous revision of the source data: the tools refer to the most recent data (as shown in the Eurostat database under Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (employ)) while the text refers to data from May 2019.

Full article

Employment rates by sex, age and educational attainment level

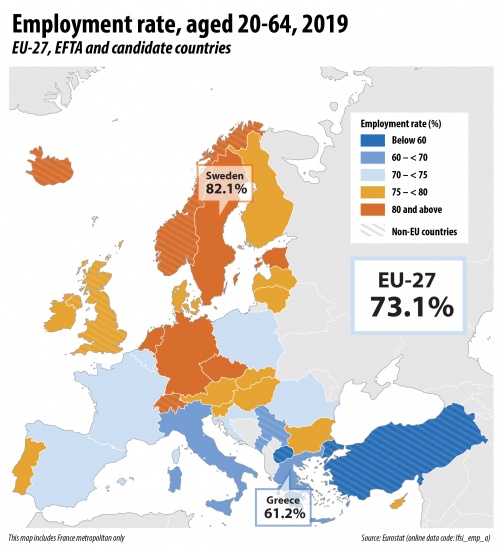

In 2018, the EU-28 employment rate for persons aged 20 to 64, as measured by the EU labour force survey (EU LFS), stood at 73.1 %, the highest annual average ever recorded for the EU. Behind this average, large differences between countries can nevertheless be found (see Map 1 and Tool 1). Sweden is the only EU Member State with an employment rate above 80 % (82.6 %). Such a high rate is also observed in the EFTA countries Iceland (86.5 %) and Switzerland (82.5 %). At the other end of the scale, Greece can be found with an employment rate below 60 % (59.5 %), like the following candidate countries Montenegro (59.8 %), North Macedonia (56.1 %) and Turkey (55.6 %).

One of the main targets of the EU 2020 strategy at EU level is to raise, by the year 2020, the employment rate of the population aged 20-64 to at least 75 %. In 2018, fourteen EU Member States had a rate equal to 75 % or above, namely six Nordic and Baltic Member States (Denmark, Sweden, Lithuania, Latvia, Finland and Estonia) as well as five North Sea and central Member States (the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria and Czechia) plus Slovenia, Malta and Portugal, see Map 1. Three non-EU countries, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland also had high employment rates of above 75 %.

At the other end, the employment rate was far from the EU target, i.e. below 70 %, in four EU Member States of South East of Europe ( Greece, Croatia, Italy and Romania) and in Belgium and Spain, with the lowest rate recorded in Greece (59.5 %).

The interactive line chart (see Tool 1) shows how the employment rate has changed since 2002 by country. By clicking on the icons at the bottom of the tool, development for specific breakdowns of the employment rate can be observed: from left to right, you can switch from the total population to women, men, youth and senior population, respectively.

In the period between 2002 and 2018, the employment rate for the total population aged 20-64 increased by 6.4 percentage points in the EU-28, from 66.8 % to 73.2 %. However, countries have experienced very different labour market situations over the past years. The employment rate increased, between 2002 and 2018, in all countries except in Greece (-3.0 percentage points (p.p.)) and in Cyprus (-1.0 p.p.). The increase is larger than the EU average of 6.4 p.p. in all countries that entered the EU after 2004 (except Cyprus) as well as in Germany. The largest increases are observed in Bulgaria (where the employment rate increased 16.6 p.p. from 55.8 % in 2002 to 72.4 % in 2018) and in Malta (17.3 p.p. from 57.7 % to 75.0 %).

In all EU Member States, the employment rate for men was higher than for women in 2018. This is also true for all years between 2002 and 2018, with two exceptions: Latvia in 2010 and Lithuania in 2009-2010. The evolution of the employment rate of men and women over the 2002-2018 period however differed. By clicking on the second and third icons of Tool 1, you can see the evolution of the employment rate of men and women respectively, since 2002.

Tool 1: Employment (total, female, male, youth and senior), 2002-2018

(% of the population aged 20 to 64)

Source: Eurostat

Since 2002, the employment rate of women has increased overall in Europe, with an increase of 9.2 p.p. at EU level. The largest increases for female employment rates between 2002 and 2018 were observed in Malta (+29.0 p.p), Bulgaria (+16.0 p.p) and Germany (+14.0 p.p.). In 2018, the highest employment rates for women were found in Iceland (83.2 %) and Sweden (80.4 %), whereas the lowest female employment rates were recorded in Greece (49.1 %) and Italy (53.1 %).

The increase at EU level of the employment rate for men was more limited (+3.5 p.p.) than for women during the period 2002-2018. The male employment rate even decreased in 11 EU Member States, with the most visible changes observed in Greece (-8.3 p.p. from 78.4 % in 2002 to 70.1 % in 2018) and Cyprus (-6.5 p.p. from 85.8 % to 79.3 %).

As a consequence, the employment rate gap between women and men decreased at EU level from 17.3 p.p. in 2002 to 11.6 p.p. in 2018. The same trend was observed in all EU Member States except Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Sweden, Poland, Slovakia and Romania. The decrease was especially strong in Malta (employment gender gap changed by -24.3 p.p.) due to the increasing female employment rate, as well as in Spain (-17.4 p.p.) and Luxembourg (-17.3 p.p.) as a result of a combined decrease of the male employment rate and increase of female employment rate.

Regarding the fourth and fifth icons of Tool 1, they show that the employment rate of persons aged 15-24 (youth employment) has decreased at EU level between 2002 and 2018, whereas the employment rate of persons aged 55-64 (senior employment) has increased during the same period. The decrease in the youth employment rate is particularly visible in Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Greece. On the other hand, Germany, Bulgaria and Slovakia recorded the largest increase in the employment rate of persons aged 55-64.

Employment rates also vary considerably according to the level of educational attainment (see Tool 2). The rates analysed by level of educational attainment are based on the age group 25 to 64, as younger persons may still be in education, particularly in tertiary education, and this may significantly impact the employment rates.

Tool 2: Employment rate by level of education, 2002-2018

(% of the population with low/medium/high level of education aged 25 to 64)

Source: Eurostat

The employment rate of persons aged 25-64 who had completed a tertiary education (short-cycle tertiary, bachelor’s, master’s or doctoral levels (or equivalents)) (ISCED levels 5-8) was 85.8 % at EU level in 2018. This is much higher than the rate for those who had attained no more than a primary or lower secondary education (ISCED levels 0-2), i.e. 56.8 %. The EU-28 employment rate of persons with at most an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED levels 3-4) is situated between the two previous rates, at 76.4 %.

In addition to having the lowest probability of finding a job (among the three education level groups), persons who have at most a lower secondary education (ISCED levels 0-2) were also hit hardest by the crisis: the employment rate for this group fell by 5.0 p.p. between 2007 and 2013 at EU level. The corresponding number for those with a medium level of education (ISCED levels 3-4) was 1.7 p.p., and for those with a high level of education (ISCED levels 5-8) 1.7 p.p.

Tool 2 demonstrates the importance of having at least a medium level of education for the chance of finding a job. Indeed, for example in Slovakia, in 2018 the employment rate of persons with a low level of education was 37.9 %, this rate is much smaller than the employment rate of persons with a medium level of education (76.9 %) and of persons with a high level of education (82.6 %). This situation is also largely visible in Croatia (37.5 % for low level of education versus 68.5 % for medium level of education), Czechia (52.2 % vs 83.5 %), Bulgaria (47.0 % vs 78.5 %) and Poland (43.1 % vs 70.4 %).

Persons with more than one job more numerous among those with a high level of education

Figure 1 shows that the share of people having more than one job is small, and that persons with a high level of education (ISCED levels 5-8) are more likely to have a second job than persons with a medium (ISCED levels 3-4) or a low (ISCED levels 0-2) level of education. In the EU-28 in 2018, 5.0 % of persons with a tertiary education had more than one job, while this share was 2.8 % for persons with a low level of education and 3.8 % for persons with a medium level of education.

The share of people having more than one job with a high level of education was highest in the Netherlands (10.1 %), Estonia (9.8 %) Sweden (8.8 %) and Denmark (8.3 %). The gap between persons with a low and a high level of education for persons with more than one job was strongly visible in Latvia (gap of 6.9 p.p.), followed by Estonia (gap 6.7 p.p.), Portugal (gap 5.6 p.p.) and the Netherlands (gap 4.9 p.p.). Nevertheless, in some countries, the rate of people having more than one job was slightly higher among people with a low level of education than among those with a high level of education; the biggest difference in this direction was in France (gap -1.8 p.p.).

Prevalence of professionals, lower status employees as well as service and sales workers

In terms of occupations, professionals were the largest group in the EU-28 in 2018(see Figure 2a) with 20.0 % of employed persons. This was followed by service and sales workers with 16.4 %, and then technicians and associate professionals with 16.3 %. At the other end, the two smallest groups were skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers (3.0 %) and armed forces occupations (0.6 %).

However, considering occupation alone only gives a restricted picture of the economic, social and cultural characteristics of employed persons. That is why a broader classification called the ESeG (European Socio-economic Groups) has been introduced. This combines occupation with the status in employment. Using this classification, professionals (20.0 %) were still the largest group in the EU-28 in 2018 (see Figure 2b), but this time followed by the lower status employees with 18.2 %, and then skilled industrial employees with 16.2 % of employed persons.

(% of total employment)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egais)

(% of total employment)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_esega)

Rise of part-time and temporary work

The proportion of the EU-28 workforce, in the age group 20-64 years, reporting that their main job was part-time increased slowly but steadily from 14.9 % in 2002 to 19.0 % in 2015, and then fell marginally to 18.5 % in 2018 (see Tool 3 icon 1). By far the highest proportion of part-time workers in 2018 was found in the Netherlands (46.8 %), followed by Austria, Germany, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Denmark where part-time work accounted in each case for more than a fifth (21 %) of those in employment. By contrast, part-time employment was relatively uncommon in Bulgaria (1.8 % of those in employment) as well as Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia and Poland (between 4.2 % and 6.2 %). Part-time work increased since 2002 in all EU Member States, except in Romania (-3.1 p.p.), Poland (-2.7 p.p.), Lithuania (-2.6 p.p.), Latvia (-1.7 p.p.), Croatia (-1.6 p.p.), Bulgaria (-0.9 p.p.) and Portugal (-0.6 p.p.).

The second and third icons of Tool 3 show that part-time work differs significantly between men and women. Just below one third (30.8 %) of women aged 20-64 who were employed in the EU-28 worked on a part-time basis in 2018, a much higher proportion than the corresponding share for men (8.0 %). Close to three quarters (73.8 %) of women and somewhat less than one quarter of men (23.0 %) employed in the Netherlands worked on a part-time basis in 2018, the highest rates among the EU Member States. The biggest increase in percentage points in part-time employment between 2002 and 2018 was for women in Italy (15.6 p.p. from 16.8 % to 32.4 %) and for men in Switzerland (7.9 p.p. from 9.1 % to 17.0 %), while the biggest decrease for women was in Iceland (-11.8 p.p. from 42.3 % to 30.5 %) and for men in Lithuania (-3.2 p.p. from 8.3 % to 5.1 %).

Tool 3: Part-time employment (total, female and male) and temporary employment (total, female and male), 2002-2018

(% of total/female/male employees aged 20 to 64)

Source: Eurostat

From 2002 to 2018, the share of persons with a permanent contract slightly decreased in the EU-28, while the share of temporary employees rose from 11.2 % in 2002 to 13.2 % in 2018 (see Tool 3 icon 4). The number of persons temporarily employed varies among EU Member States: the highest percentage of persons having a temporary contract were recorded in 2018 in Spain (26.4 %), Poland (23.9 %) and Portugal (21.5 %). At the other end, the lowest shares of temporary contracts can be found in Romania (1.1 %), Lithuania (1.4 %) and Latvia (2.6 %).

The comparison of temporary employment between men and women (see Tool 3 icons 5 and 6) shows that the gender gap was not so big in 2018 at EU level, with 12.6 % for men and 13.8 % for women.

Tool 4 presents the share of employees, aged 20-64, with a contract of limited duration by European Socio-economic Group (ESeG). For most countries, managers are the least likely to have contracts of limited duration while lower status employees are most likely to have such contracts. However, the levels differ markedly across countries: 39.2 % of lower status employees in Poland are in this situation, whereas the corresponding share for Romania is only 2.6 %. The considerable range in the propensity to have limited duration contracts between EU Member States may, at least to some degree, reflect the national practices, the supply and demand of labour, the employer assessments regarding potential growth/contraction and the ease with which employers can hire and fire.

Tool 4: Employees with limited duration contracts by European socio-economic group, 2018

(% of employees aged 20-64)

Source: Eurostat

Temporary employment agency workers

The percentage of employed persons who work for a temporary work agency is low. At EU level, this was the case for 2.2 % of the employed men and 1.5 % of the employed women aged 20-64 in 2018. Figure 3 shows that the use of this form of employment is the highest in Slovenia (4.2 % for men, 6.0 % for women) and Spain (4.1 % for men, 3.6 % for women), whereas it barely exists in Hungary (0.3% each), Greece (0.2 % for men and 0.3 % for women) and the United Kingdom ( 0.6 % for men and 0.5 % for women).

The gap between men and women was the highest in France (2.0 p.p.), followed by the Netherlands and Austria (1.6 p.p. each). However, the difference between men and women is lower than 1 p.p. in the majority of the EU Member States. Women are more likely than men to work as temporary agency workers in 7 EU Member States (Greece, Croatia, Denmark, Poland, Latvia, Ireland and Slovenia). In Hungary the percentage of persons working for a temporary agency is the same for men and women.

Precarious employment

In 2018, 2.1 % of men and women aged 20-64 in the EU-28 had a precarious employment situation (having a work contract of only up to 3 months). The overall proportion of persons in precarious employment was the highest in Croatia, France, Spain, Italy and Slovenia, as well as the candidate countries Serbia, Montenegro and North Macedonia (Figure 4). The differences between men and women are lower than 1 p.p. in all countries except in Finland (1.1 p.p.), Serbia (1.3 p.p.) and Turkey (2.0 p.p.). Women slightly tend more than men to have a precarious employment situation in half of the EU Member States .

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Coverage

The economically active population (labour force) comprises employed and unemployed persons. The EU LFS defines persons in employment as those aged 15 and over, who, during the reference week, performed some work, even for just one hour per week, for pay, profit or family gain. The labour force also includes people who were not at work but had a job or business from which they were temporarily absent, for example, because of illness, holidays, industrial disputes, education or training.

Employment can be measured in terms of the number of persons or jobs, in full-time equivalents or in hours worked. All the estimates presented in this article use the number of persons; the information presented for employment rates is also built on estimates for the number of persons. Employment statistics are frequently reported as employment rates to discount the changing size of countries’ populations over time and to facilitate comparisons between countries of different sizes. These rates are typically published for the working age population, which is generally considered to be those aged between 15 and 64 years, although the age range of 16 to 64 is used in Spain and the United Kingdom, as well as in Iceland. The 15 to 64 years age range is also a standard used by other international statistical organisations (although the age range of 20 to 64 years is given increasing prominence by some policymakers as a rising share of the EU population continue their studies into tertiary education).

Main concepts

Some main employment characteristics, as defined by the EU LFS, include:

- employees are defined as those who work for a public or private employer and who receive compensation in the form of wages, salaries, payment by results, or payment in kind; non-conscript members of the armed forces are also included;

- self-employed persons work in their own business, farm or professional practice. A self-employed person is considered to be working during the reference week if she/he meets one of the following criteria: works for the purpose of earning profit; spends time on the operation of a business; or is currently establishing a business;

- the distinction between full-time and part-time work is generally based on a spontaneous response by the respondent. The main exceptions are the Netherlands and Iceland where a 35 hours threshold is applied, Sweden where a threshold is applied to the self-employed, and Norway where persons working between 32 and 36 hours are asked whether this is a full- or part-time position;

- indicators for employed persons with a second job refer only to people with more than one job at the same time; people having changed job during the reference week are not counted as having two jobs;

- an employee is considered as having a temporary job if employer and employee agree that its end is determined by objective conditions, such as a specific date, the completion of an assignment, or the return of an employee who is temporarily replaced. Typical cases include: people in seasonal employment; people engaged by an agency or employment exchange and hired to a third party to perform a specific task (unless there is a written work contract of unlimited duration); people with specific training contracts.

The level of education refers to the educational attainment level, i.e. the highest level of education successfully completed. Low level of education refers to ISCED levels 0-2 (less than primary, primary and lower secondary education), medium level refers to ISCD levels 3 and 4 (upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education) and high level of education refers to ISCED levels 5-8 (tertiary education).

The European Socio-economic Groups (ESeG) is a derived classification which allows the grouping of individuals with similar economic, social and cultural characteristics throughout the European Union, based only on core social variables to ensure comfortable use in all social surveys providing comparable results. The main core social variables used are "ILO working status", “Status in employment”, “Occupation in employment” (according to ISCO-08) and “Self-declared labour status”. For the detailed classification and explanatory notes, please consult ESeG page on the Eurostat classification server RAMON.

Datasets

Most of the indicators presented in this article are from datasets that form part of the labour force survey main indicators (datasets starting with the letters lfsi). These main indicators differ from the datasets with the detailed annual and quarterly survey results (datasets starting with the letters lfsa and lfsq) in that the detailed survey results are exclusively based on microdata from the labour force survey, whereas the main indicators have received additional treatment. The most common additional adjustments are corrections of the main breaks in the series and estimations of missing values. These adjustments produce notable differences between the two data sets for some years.

The datasets of the labour force survey main indicators are the most complete and reliable collection of employment and unemployment data available from the labour force survey. However, as they do not offer analysis of all background variables, it is in some cases necessary to use the detailed survey results as well.

Context

Employment statistics can be used for a number of different analyses, including macroeconomic (looking at labour as a production factor), productivity or competitiveness studies. They can also be used to study a range of social and behavioural aspects related to an individual’s employment situation, such as the social integration of minorities, or employment as a source of household income.

Employment is both a structural indicator and a short-term indicator. As a structural indicator, it may shed light on the structure of labour markets and economic systems, as measured through the balance of labour supply and demand, or the quality of employment. As a short-term indicator, employment follows the business cycle; however, it has limits in this respect, as employment is often referred to as a lagging indicator.

Employment statistics are at the heart of many EU policies. The European employment strategy (EES) was launched at the Luxembourg jobs summit in November 1997 and was revamped in 2005 to align the EU’s employment strategy more closely to a set of revised Lisbon objectives, and in July 2008, employment policy guidelines for the period 2008–2010 were updated. In March 2010, the European Commission launched the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth; this was formally adopted by the European Council in June 2010. The European Council agreed on five headline targets, the first being to raise the employment rate for women and men aged 20 to 64 years old to 75 % by 2020. EU Member States may set their own national targets in the light of these headline targets and draw up national reform programmes that include the actions they aim to undertake in order to implement the strategy. The implementation of the strategy might be achieved, at least in part, through the promotion of flexible working conditions — for example, part-time work or work from home — which are thought to stimulate labour participation. Among others, initiatives that may encourage more people to enter the labour market include improvements in the availability of childcare facilities, providing more opportunities for lifelong learning, or facilitating job mobility. Central to this theme is the issue of ‘flexicurity’: policies that simultaneously address the flexibility of labour markets, work organisation and labour relations, while taking into account the reconciliation of work and private life, employment security and social protection. In line with the Europe 2020 strategy, the EES encourages measures to help meet three headline targets by 2020, namely, for:

- 75 % of people aged 20 to 64 to be in work;

- rates of early school leaving to reduce below 10 %, and for at least 40 % of 30 to 34-year-olds to have completed a tertiary education;

- at least 20 million fewer people to be in or at-risk-of-poverty and social exclusion.

The slow pace of recovery from the financial and economic crisis and mounting evidence of rising unemployment led the European Commission to make a set of proposals on 18 April 2012 for measures to boost jobs through a dedicated employment package. These proposals, among others, targeted the demand-side of job creation, setting out ways for EU Member States to encourage hiring by reducing taxes on labour or supporting business start-ups. The proposals also aimed to identify economic areas with the potential for considerable job creation, such as the green economy, health services and information and communications technology.

In December 2012, in the face of high and still rising youth unemployment in several EU Member States, the European Commission proposed a Youth employment package (COM(2012) 727 final). This package was a follow-up to the actions on youth laid out in the wider employment package and made a range of proposals, including:

- that all young people up to the age of 25 should receive a quality offer of a job, continued education, an apprenticeship or a traineeship within four months of leaving formal education or becoming unemployed (a youth guarantee);

- a consultation of European social partners on a quality framework for traineeships to enable young people to acquire high-quality work experience under safe conditions;

- a European alliance for apprenticeships to improve the quality and supply of apprenticeships available and outlining ways to reduce obstacles to mobility for young people.

Efforts to reduce youth unemployment continued in 2013 as the European Commission presented a Youth employment initiative (COM(2013) 144 final) designed to reinforce and accelerate measures outlined in the Youth employment package. It aimed to support, in particular, young people not in education, employment or training in regions with a youth unemployment rate above 25 %. There followed another Communication titled ‘Working together for Europe's young people – A call to action on youth unemployment' (COM(2013) 447 final) which was designed to accelerate the implementation of the youth guarantee and provide help to EU Member States and businesses so they may recruit more young people.

One of the main priorities of the College of Commissioners that entered into office in 2014 is to focus on boosting jobs, growth and investment, with the goal of cutting regulation, making smarter use of existing financial resources and public funds. In February 2015, the European Commission published a series of country reports, analysing the economic policies of EU Member States and providing information on EU Member States priorities for the coming year to boost growth and job creation. In the same month, the European Commission also proposed to make EUR 1 billion from the Youth employment initiative available in 2015 so as to increase by up to 30 times the pre-financing EU Member States could receive to boost youth employment rates, with the aim of helping up to 650 000 young people into work.

In June 2016, the European Commission adopted a Skills Agenda for Europe (COM(2016) 381/2) under the heading ‘Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness’. This is intended to ensure that people develop the skills necessary for now and the future, in order to boost employability, competitiveness and growth across the EU.

More recently, the European Pillar of Social Rights has been jointly signed by the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission on 17 November 2017. Employment and social policies are the main fields of interest of the European Pillar of Social Rights, which is about delivering new and more effective rights for citizens. It has 3 main categories: (1) Equal opportunities and access to the labour market, (2) Fair working conditions and (3) Social protection and inclusion. In particular, today's more flexible working arrangements provide new job opportunities especially for the young but can potentially give rise to new precariousness and inequalities. Building a fairer Europe and strengthening its social dimension is a key priority for the Commission. The European Pillar of Social Rights is accompanied by a ‘social scoreboard’ which will monitor the implementation of the Pillar by tracking trends and performances across EU countries in 12 areas and will feed into the European Semester of economic policy coordination. The scoreboard will also serve to assess progress towards a social ‘triple A’ for the EU as a whole.

Direct access to

- LFS main indicators (t_lfsi)

- Population, activity and inactivity - LFS adjusted series (t_lfsi_act)

- Employment - LFS adjusted series (t_lfsi_emp)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (t_une)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (t_lfsa)

- LFS series - Specific topics (t_lfst)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Employment and activity - LFS adjusted series (lfsi_emp)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- Labour market transitions - LFS longitudinal data (lfsi_long)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998 onwards) (lfsq)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- LFS series - Specific topics (lfst)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (lfso)

Publications

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- Labour Force Survey in the EU, candidate and EFTA countries — Main characteristics of national suveys, 2017, 2018 edition

- Quality Report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2017, 2019 edition

ESMS metadata files and EU-LFS methodology

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- Employment growth and activity branches - annual averages (ESMS metadata file — lfsi_grt_a_esms)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (ESMS metadata file — lfso_esms)

- LFS main indicators (ESMS metadata file — lfsi_esms)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- LFS series - detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998 onwards) (ESMS metadata file — lfsq_esms)