Archive:Being young in Europe today - education

- Data extracted in December 2017. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: June 2021

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Being young in Europe today.

A paper edition of the publication was also published in 2015. In late 2017, a decision was taken to update the online version of the publication (subject to data availability).

The right to education for children and young people contributes to their overall development and consequently lays the foundations for success later in life in terms of employability, social integration, health and well-being. Education and training have the potential to play a crucial role in counteracting the negative effects of poverty and social exclusion. The European Union (EU) therefore promotes policies that seek to ensure that all children and young people are able to access and benefit from high-quality education and training.

Each EU Member State is responsible for its own system of education and training, while the EU’s role consists of coordinating and supporting the actions of the Member States as well as addressing common challenges. By so doing, the EU offers a forum for exchange of best practices, gathers and disseminates information and statistics, while providing advice and support for education and training policy reforms.

This article presents a range of statistics covering children’s and young people’s education in the EU, the main sources of data being the joint UNESCO-UIS/OECD/Eurostat (UOE) questionnaires on education statistics. Childcare data, coming from the EU’s data collection for statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), complement the analysis for the youngest children. Data on outcomes of education, collected through the EU labour force survey (LFS), are also analysed, providing information on educational attainment and early school leavers.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_caindformal)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (educ_ipart) and (educ_uoe_enra10)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enra10)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_caindformal)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_caparents)

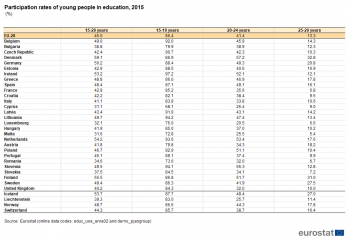

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enra02) and (demo_pjangroup)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_enrl1tl), (demo_pjangroup) and (educ_uoe_enra02)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_enrl1tl), (demo_pjangroup) and (educ_uoe_enra02)

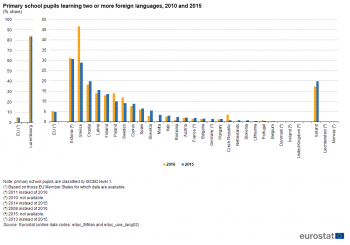

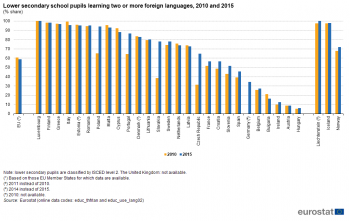

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (educ_thfrlan) and (educ_uoe_lang02)

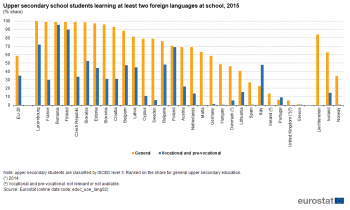

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (educ_thfrlan) and (educ_uoe_lang02)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_lang02)

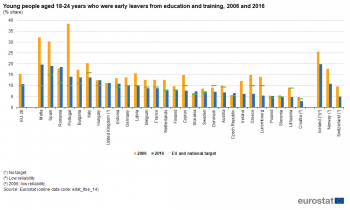

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_14)

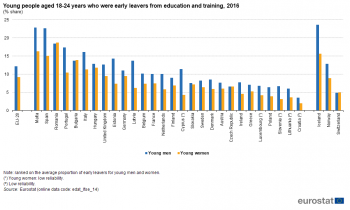

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_14)

(% share)

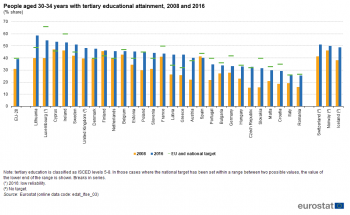

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_03)

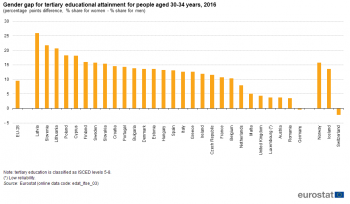

(percentage points difference, % share for women - % share for men)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_03)

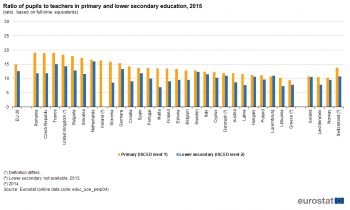

(ratio, based on full-time equivalents)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_perp04)

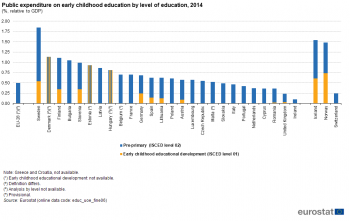

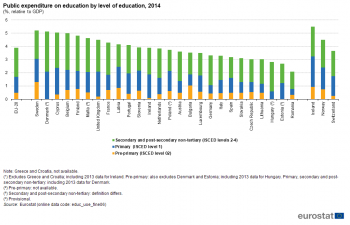

(%, relative to GDP)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_fine06)

(%, relative to GDP)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_fine06)

Main statistical findings

Childcare attendance and participation in education

Early childhood education and care can potentially increase the well-being of young children, advance children’s rights and ensure that all children have a fair start in life. A number of studies during the last decade have shown the crucial role played by early life experiences on cognitive functions, educational attainment and life chances.

Increasing access to high-quality early childhood education and care is one of the key goals outlined within the EU’s strategic framework for education and training (ET2020) which set the goal of having at least 95 % of young children (between the ages of four and the compulsory school age) participating in early childhood education by 2020.

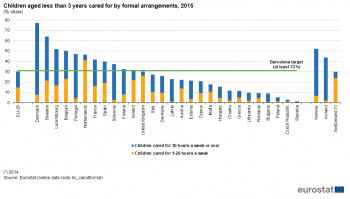

Childcare services for children under the age of three are also covered, as the ‘Barcelona target’ (defined by the European Council in 2002) foresees improving the provision of childcare across the EU Member States through removing some of the disincentives to female labour force participation, such that at least 33 % of children under three years of age receive childcare.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of children aged less than 3 years who were cared for by formal arrangements, namely, in day-care centres; these participation rates are analysed by the number of hours during which care is provided (over and under 30 hours per week) which may reflect, at least to some degree, the different patterns of part-time/full-time work of parents across the EU Member States (for example, a particularly high share of the workforce in the Netherlands works on a part-time basis). The information presented should also be considered with respect to different patterns of family structure and attitudes concerning the time that parents (in particular mothers, but also fathers) may or should spend with young children before returning/looking for work. In some southern and eastern EU Member States, it remains relatively common for young children to be cared for by their extended family (often grandparents), whereas families tend to be more dispersed in western and Nordic Member States, which may at least in part explain why they often have a higher demand for and supply of childcare services.

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FORMAL AND INFORMAL CHILDCARE?

Formal childcare:

- childcare provided at a day-care centre that is organised/controlled by a public or private body.

Informal childcare:

- childcare provided by a professional child-minder at the child’s home or at the child-minder’s home;

- childcare provided by grandparents, other household members (other than parents), other relatives, friends or neighbours.

In 2015, the lowest levels of formal childcare for children aged less than 3 years were recorded in eastern EU Member States

In 2015, some 30.3 % of children aged less than 3 years in the EU-28 received some formal childcare; this average remained 2.7 percentage points below the Barcelona target. There were however large differences between the EU Member States: nine had attained a level of formal childcare that was above the Barcelona target, with more than half of all children under the age of three receiving formal childcare in Denmark (77.3 %), Sweden (64.0 %), Luxembourg (51.8 %) and Belgium (50.1 %). By contrast, less than 1 in 10 children under the age of three received formal childcare in Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia (where the lowest share was recorded, at 1.1 %).

Analysing the results by the time spent in formal childcare, more than one third of the children aged less than 3 in Denmark, Portugal, Sweden, Luxembourg and Slovenia received at least 30 hours of care in 2015. The Netherlands was the only EU Member State where more than one third of all children aged less than 3 received between 1 and 29 hours of formal childcare.

Children who have attended pre-primary education tend in most countries to perform better in school than those who have not, even after accounting for their socioeconomic background. Early childhood education may help to build a strong foundation for lifelong learning and to ensure fair access to learning opportunities later in life. Some countries have recognised this by making pre-primary education almost universal for children by the time they are three or four years old [1].

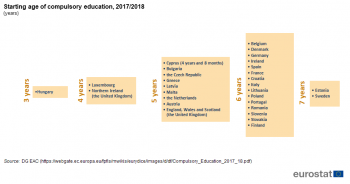

Hungary is the only EU Member State where children started compulsory education at the age of three during the 2017/2018 school year, while in Luxembourg and Northern Ireland (the United Kingdom) children started compulsory education at the age of four. In a majority of the EU Member States the starting age for compulsory education was either five or six years, although it rose to seven years for children in Estonia and Sweden. There is a trend within the EU Member States towards requiring children to start education at a younger age, with several countries having lowered their compulsory starting ages and others making pre-school attendance compulsory.

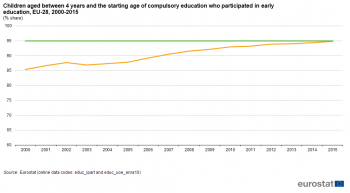

Since 2003, participation in early childhood education increased steadily across the EU-28

Figure 3 presents statistics for one of the headline targets of the EU’s strategic framework for education and training (ET2020), namely, that the participation rate of children between the ages of four and the starting age of compulsory education should be at least 95 % by 2020. Across the EU-28, there was a steady increase in this share from 2003. By 2015 (the latest date for which information is available), some 94.8 % of children between the ages of four and the starting age of compulsory education were participating in early education. As such, the EU-28 participation rate for early education in 2015 was just 0.2 points below the target.

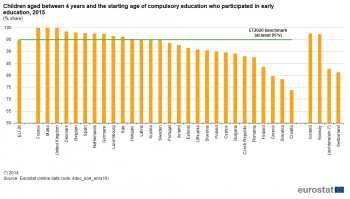

In 2015, there were 14 EU Member States (see Figure 4) where at least 95 % of children aged between four years and the starting age of compulsory education participated in early education. Every child in France, Malta and the United Kingdom did so, while the other Member States that recorded participation rates of at least 95 % included Denmark, Belgium, Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, Luxembourg, Italy, Hungary, Latvia, Austria and Sweden. There were several Member States that recorded participation rates that were close to the ET2020 target, as 90-94 % of the children aged between four years and the starting age of compulsory education participated in early education in Portugal, Ireland, Estonia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Poland. This left eight Member States where the participation rate was below 90 %: of these, there were three where the share of children participating in early education was below 80 %, namely, Croatia (73.8 %), Slovakia (78.4 %) and Greece (79.6 %).

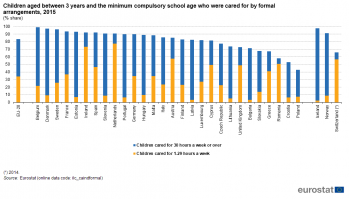

The number of hours that young children attend formal arrangements (including pre-school education and childcare at day-care centres) is considered an important indicator for a child’s development. Indeed, young children that spend a considerable period of time in such care are likely to receive more individualised instruction and to have more time interacting with their peers. Across the EU-28, some 83.3 % of children from the age of three to the minimum compulsory school age attended formal childcare arrangements in 2015: almost half (49.4 %) attended at least 30 hours per week of early childhood education and care, while around a third (33.9 %) received between 1 and 29 hours (see Figure 5).

In 2015, the highest share of children between the age of three and the minimum compulsory school age who received at least 30 hours per week of formal childcare was recorded in Denmark (88.0 %), while more than four out of every five young children also received at least 30 hours of care in Estonia (86.1 %), Portugal (83.5 %) and Slovenia (82.1 %). At the other end of the range, less than one quarter of children between the age of three and the minimum compulsory school age received at least 30 hours per week of formal childcare in the United Kingdom, this share falling to less than one fifth in Ireland, less than one seventh in the Netherlands, while the lowest share was recorded in Romania (7.3 %).

In most of the EU Member States, a higher proportion of children between the age of three and the minimum compulsory school age received at least 30 hours per week of formal childcare rather than 1-29 hours. In 2015, this pattern was particularly apparent in the Baltic Member States, Bulgaria and Portugal, where the share of young children receiving formal childcare for at least 30 hours per week was more than 10 times as high as for young children receiving 1-29 hours of care per week. By contrast, more than half of the young children between the age of three and the minimum compulsory school age received 1-29 hours per week of formal childcare in the Netherlands, Ireland, Austria and Romania. Poland was the only Member State where a majority (57.0 %) of young children received no formal childcare in 2015.

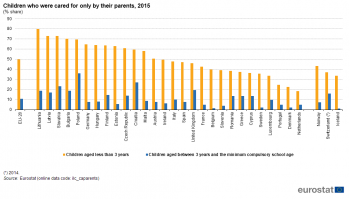

Half the children aged less than 3 years in the EU-28 were cared for only by their parents in 2015

As shown above, early childhood education and care arrangements vary considerably between the EU Member States. While many parents make use of formal childcare facilities, others choose to care for their children themselves. This is particularly true for very young children, as in 2015 approximately half (49.8 %) of all children aged less than 3 years in the EU-28 were cared for only by their parents (see Figure 6). The highest share was recorded in Lithuania (79.9 %), while 70-73 % of children aged less than 3 were exclusively cared for by their parents in Latvia, Slovakia and Bulgaria. At the other end of the range, less than one quarter of children aged less than 3 were exclusively cared for by their parents in Portugal (24.4 %), Denmark (22.4 %) and the Netherlands (18.5 %).

A similar analysis reveals that for somewhat older children there was a considerably smaller proportion of children who were exclusively cared for by their parents. In 2015, around 1 in 10 (10.9 %) children in the EU-28 between the age of three and the minimum compulsory school age were cared for only by their parents. Much higher shares were recorded in Poland (36.0 %), Croatia (26.8 %) and Slovakia (23.0 %), whereas in Belgium, Denmark and Sweden, the share of children between the age of three and the minimum compulsory school age who were cared for exclusively by their parents fell to less than 3.0 %.

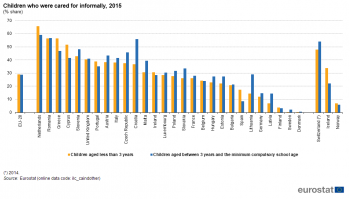

In 2015, more than one quarter of all young children in the EU-28 were cared for informally

Some children are cared for by other types of informal childcare, in other words, they may be cared for by a professional child-minder (at the child’s home or the child-minder’s home), by grandparents, other household members (outside of parents), relatives, friends or neighbours. Figure 7 shows that across the EU-28 more than one quarter of all young children (up to the minimum compulsory school age were cared for informally. In 2015, the propensity to make use of informal care in the EU-28 was almost identical for children aged less than 3 (28.9 %) and children aged between three and the minimum compulsory school age (28.8 %). Note that informal childcare can — although it does not have to — be combined with formal childcare.

In 2015, almost three quarters (65.7 %) of children aged less than 3 in the Netherlands received informal childcare; Romania, Greece and Cyprus were the only other EU Member States to report that more than half of their children aged less than 3 received such care. By contrast, less than 1 in 10 children aged less than three received informal childcare in the northern Member States of Latvia, Finland, Sweden or Denmark.

A similar analysis for somewhat older children reveals that the Netherlands, Romania and Croatia were the only EU Member States where, in 2015, a majority of the children between the age of three and the compulsory school age received informal childcare. At the other end of the range, less than 1 in 10 children from this age group received informal childcare in Spain, Finland, Sweden and Denmark.

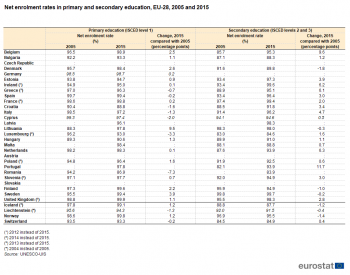

A simple average of enrolment rates among the EU Member States suggests that more than 19 out of every 20 children attended primary or secondary education in 2015

The net enrolment rate in primary (respectively secondary) education is the percentage of children of the primary (respectively secondary) school age who are enrolled in primary (respectively secondary) education.

The net enrolment rate for primary education was 95.0 % or above in 19 of the 25 EU Member States for which data are available in 2015 (note that earlier reference years are used for some Member States), rising above 99.0 % in Spain, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom (2014 data). By contrast, Croatia (88.8 %) and Romania (86.9 %) were the only Member States where more than 1 in 10 children were not enrolled in the primary education system.

Enrolment rates for secondary education were often slightly lower than those recorded for primary education, which may reflect some older children choosing to leave the system before the end of upper secondary education. Nevertheless, enrolment rates for secondary education were higher than 95.0 % in 11 of the 24 EU Member States for which data are available in 2015 (note again that earlier reference years are used for some Member States). In France (2014 data), Ireland (2012 data) and Sweden, enrolment rates were above 99.0 %, while at the other end of the range they were less 90.0 % in Denmark, Malta, Bulgaria, Luxembourg (2014 data) and Romania (see Table 1). It should be noted that the legal requirements concerning the start and end of compulsory education may be one influence on these enrolment rates (which are expressed as a percentage of the total population of the same age group that officially corresponds to each level).

In 2015, there were larger discrepancies between EU Member States concerning enrolment rates for education among young adults than for children

Of the 88.8 million young people aged 15-29 years who were resident in the EU-28 in 2015, almost 40 million were enrolled in education. While the enrolment rate for young people aged 15-29 years averaged 45.0 % across the EU-28 (see Table 2), fewer than one third of all young people in Luxembourg, Malta and Cyprus were enrolled in education; this may be attributed, at least in part, to a relatively high share of young people choosing to study abroad (possibly to study a specific subject that might not be available within the national systems) while they remained on the population register and were therefore considered in the count for the number of inhabitants. By contrast, there were five EU Member States where more than half of all young people aged 15-29 years were enrolled in an education programme: Denmark had the highest share (59.1 %), followed by Finland (55.5 %), the Netherlands (54.2 %), Ireland (53.2 %) and Germany (50.2 %).

As may be expected, enrolment rates for young people in education generally decreased as a function of age. For example, while 86.4 % of young people aged 15-19 years in the EU-28 were enrolled in education, the corresponding share for young people aged 20-24 years was 41.4 %, falling to 13.3 % among young people aged 25-29 years.

In 2015, more than two fifths of young people aged 20-24 years in the EU-28 participated in education, although there were considerable disparities between the individual EU Member States. There were six Member States where more than half of the young people aged 20-24 years continued to participate in education, with the highest shares recorded in Denmark (57.2 %) and Slovenia (55.3 %), while enrolment rates in the Netherlands, Ireland, Finland and Poland were all within the range of 51-53 %. By contrast, less than one third of the young people aged 20-24 years in Romania and the United Kingdom participated in education, a rate that fell to around one quarter for this subpopulation in Malta and Cyprus, and to around one fifth in Luxembourg.

Slightly more than one in eight (13.3 %) young people aged 25-29 years in the EU-28 participated in education in 2015. As for the age group 20-24 years, Denmark again recorded the highest rate (32.8 %), while the neighbouring Nordic Member States of Finland (31.0 %) and Sweden (27.5 %) recorded the next highest shares. Germany (20.8 %) was the only other Member State to report that more than one fifth of its young people aged 25-29 years participated in education. By contrast, there were eight Member States where the participation rate in education for young people aged 25-29 years fell into single-digits, with this rate less than 7.0 % in France, Romania, Luxembourg and Malta.

These disparities between EU Member States may result from a combination of factors: for example, the country specific organisation of national education systems, legal requirements concerning the end of compulsory education, the accessibility to and affordability of non-compulsory further education, the relative demand for undergraduate (Bachelor’s) and postgraduate (such as Master’s and Doctoral programmes) courses, or different economic situations and their impact on labour markets. After the age of 20, it is more common for enrolment rates to reflect socioeconomic criteria, for example, the employment situation faced by young people (who may choose to remain within the education system if they are unable to find a job) and the cost of studying rather than working.

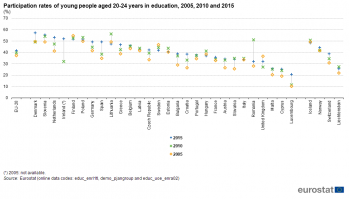

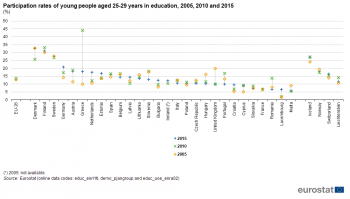

Between 2005 and 2015, participation rates for young people aged 20-24 years in education generally followed an upward pattern across the EU-28, while participation rates for young people aged 25-29 years were relatively stable (see Figures 8 and 9).

The participation rate of young people aged 20-24 years in education rose from 37.3 % in 2005 to 41.4 % in 2015, an increase of 4.2 points. The share of young people aged 20-24 years who participated in education rose at a much faster pace than this average in Ireland (note the change only covers the period between 2010 and 2015), Spain, the Netherlands, Croatia, Luxembourg and Bulgaria, where rates rose by at least 10.0 points. On the other hand, there were five EU Member States where the share of young people aged 20-24 years participating in education fell between 2005 and 2015: the largest contractions were recorded for Sweden (-4.8 points), the United Kingdom (-4.6 points) and Finland (-3.2 points), while the reductions in Lithuania and Hungary were of a smaller magnitude.

The share of young people aged 25-29 years in the EU-28 who participated in education rose from 12.9 % in 2005 to 13.3 % in 2015; it had been somewhat higher in 2010 when it reached 13.7 %, probably reflecting the lack of employment opportunities that were available in several EU Member States in the aftermath of the global financial and economic crises, which may have led some students to consider extending their education or indeed returning to education in order to improve their qualifications. This pattern was particularly evident in Greece, where the participation rate of young people aged 25-29 years jumped dramatically from 9.8 % in 2005 to 44.1 % in 2010, before returning to 17.8 % in 2015. It was also apparent, to a lesser degree (among others), in Portugal and Romania. Contrary to the developments observed for young people aged 20-24 years, there was no clear pattern as to how the participation rates of young people aged 25-29 years developed. While participation rates in Greece, the Netherlands, Austria and Luxembourg were at least 5.0 points higher in 2015 than they had been in 2005, it was almost as common to find that rates declined. For example, the participation rate of young people aged 25-29 years in education fell by at least 5.0 points between 2005 and 2015 in Slovenia and Hungary and by as much as 9.9 points in the United Kingdom.

Foreign language learning

The ability to speak one or more foreign languages promotes intercultural dialogue, improves employability of individuals and the efficiency of enterprises that trade across borders and facilitates the movement of individuals.

In 2015, the share of EU pupils in primary school (ISCED level 1) learning two or more foreign languages was 4.8 %. This figure was 0.4 points lower than five years earlier.

Figure 10 shows that Luxembourg topped the ranking of foreign language learning among the EU Member States, with more than 8 out of every 10 (83.7 %) pupils at primary school learning two or more foreign languages in both 2010 and 2015. This was considerably higher than in any of the other Member States as the next highest shares in 2015 were recorded in Estonia (30.7 %) and Greece (28.9 %), while Croatia, Latvia and Finland recorded shares within the range of 10-20 %. By contrast, in a majority of the Member States less than 5 % of primary school pupils learnt two or more foreign languages in 2015.

A comparison between 2010 and 2015 shows that in many Member States there was little change in the share of pupils at primary school who were learning two or more foreign languages; this is perhaps unsurprising given the rate at which the school curriculum may change and the need to invest in additional resources and qualified staff for teaching new subjects. That said, the number of pupils learning two or more foreign languages rose by 3.2 points in Malta and by 2.7 points in Slovakia during the period under consideration. On the other hand, the share of pupils learning two or more foreign languages fell at a rapid pace in Greece (from 46.7 % to 28.9 %), which may reflect reductions in education funding. There were also relatively large reductions in the share of primary school pupils who were learning two or more foreign languages in Poland (-4.0 points), the Czech Republic and Sweden (both -2.8 points).

THE ISCED CLASSIFICATION

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) is an instrument based on standard concepts and definitions that may be used to assemble, compile and present comparable statistics and indicators on education. The ISCED 2011 classification was adopted by the UNESCO General Conference at its 36th session in November 2011. Eurostat has applied the use of this classification for its administrative data on education statistics from reference year 2013 onwards. The notion of ‘levels’ of education within ISCED is based on grouping education programmes in relation to learning experiences, as well as the knowledge, skills and competencies which each programme is designed to impart. The ISCED level reflects the degree of complexity and specialisation of the content of an education programme:

01 Early childhood educational development — designed to support early development in preparation for participation in school and society; programmes targeting children under three years old;

02 Pre-primary education — designed to support early development in preparation for participation in school and society; school or centre-based for children aged at least three years through to the start of compulsory primary education;

1 Primary education — programmes that are typically designed to provide students with fundamental skills in reading, writing and mathematics, establishing a solid foundation for learning;

2 Lower secondary education — the first stage of secondary education that aims to build on primary education, typically with a more subject-oriented curriculum;

3 Upper secondary education — the second stage of secondary education preparing for tertiary education and/or providing skills relevant to employment (usually has an increased range of subject options and streams);

4 Post-secondary non-tertiary education — programmes that are designed to provide learning experiences that build on secondary education and prepare students for labour market entry and/or tertiary education; content is broader than secondary education, but not as complex as tertiary education;

5 Short-cycle tertiary education — programmes that are typically practical and occupationally-specific, preparing students for labour market entry or providing a pathway to other tertiary programmes;

6 Bachelor’s or equivalent level — programmes designed to provide intermediate academic and/or professional knowledge, skills and competencies leading to a first tertiary degree or equivalent qualification;

7 Master’s or equivalent level — programmes designed to provide advanced academic and/or professional knowledge, skills and competencies leading to a second tertiary degree or equivalent qualification;

8 Doctoral or equivalent level — programmes designed primarily to lead to an advanced research qualification, usually concluding with the submission and defense of a substantive dissertation of publishable quality based on original research.

In the vast majority of the EU Member States the curricula for secondary education includes at least one foreign language. Figure 11 reveals that a higher share of pupils in lower secondary education (ISCED level 2) were learning two or more foreign languages than the share recorded in primary education. In 2015, almost three fifths (58.8 %) of lower secondary school pupils in the EU were learning two or more foreign languages.

Among the EU Member States (note there is no information available for the United Kingdom), all of the lower secondary pupils in Luxembourg learnt two or more foreign languages in 2015, while this share ranged from 93-98 % in Finland, Greece, Italy, Estonia, Romania, Poland and Malta. There were a further 12 Member States where more than half of all lower secondary pupils were learning two or more languages in 2015. By contrast, only 6.0 % of lower secondary pupils in Hungary were learning two or more foreign languages, a share that stood at 8.8 % in Hungary, 12.7 % in Ireland and 16.5 % in Bulgaria; in each of the remaining Member States, more than one quarter of lower secondary pupils were learning two or more foreign languages.

Learning foreign languages in upper secondary schools: usually more common among students following general rather than vocational programmes

Figure 12 depicts the situation for foreign language learning in upper secondary education (ISCED level 3) with an analysis by programme orientation: either general or vocational/pre-vocational. Across the EU-28, 58.5 % of pupils enrolled in general upper secondary schools were learning at least two foreign languages in 2015, compared with 35.0 % of pupils who were enrolled in vocational/pre-vocational upper secondary education.

In 2015 it was relatively commonplace to find that almost all of the students following general upper secondary programmes were being taught at least two foreign languages. This was the case for every student in Luxembourg (100 %), while shares of more than 95 % were also recorded in France, Romania, Finland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Estonia and Slovenia. Learning two or more foreign languages in general upper secondary education was quite uncommon in Greece (0.8 %), the United Kingdom (5.4 %; 2014 data), Portugal (6.4 %) and Ireland (13.8 %).

Reading, mathematical and science skills: identifying where there is room for an improvement in basic skills

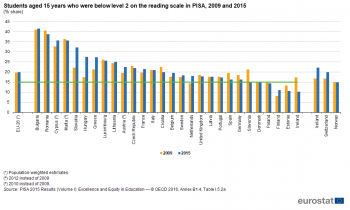

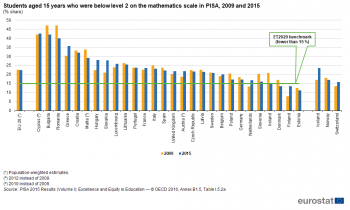

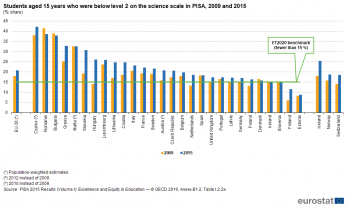

Competences in reading, mathematics and sciences are considered to be basic skills that can be applied to successful professional and civic lives. These skills also promote participation in the knowledge-based society and may help ensure the competitiveness of modern economies. As such, the Council adopted an EU-wide benchmark within the ET2020 framework to reduce the proportion of 15 year-olds underachieving in these key areas of learning, to less than 15 % by 2020.

WHAT IS PISA?

The PISA (Programme for international student assessment) survey is an internationally standardised assessment, developed by the OECD and conducted in all EU Member States (as well as a number of non-member countries), that measures the knowledge and skills of students aged 15 years in reading, mathematics and science; it also collects contextual information on the individual characteristics and socioeconomic background of students. The PISA scores are divided into six proficiency levels ranging from the lowest (level 1) to the highest (level 6): low achievement is defined as performance below level 2.

PISA results on low-achievers in reading literacy for 2015 reveal considerable differences across the EU Member States. Ireland, Estonia and Finland stood out as they had relatively few low-achievers in reading competence (some 10-11 %); Poland (14.4 %) was the only other Member State to record a share below the ET2020 framework target of 15 %. At the other end of the scale, more than 4 in 10 students aged 15 in Bulgaria recorded a PISA score that was below level 2 on the reading scale, while Romania, Cyprus and Malta also reported more than one third of their 15 year-old students were low-achievers in reading.

In PISA, reading literacy is defined as understanding, using and reflecting upon written texts, in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential and to participate in society.

Between 2009 and 2015 there was little change in the share of EU-28 students aged 15 who were below level 2 on the PISA reading scale, with an increase of 0.1 points. A majority (15 out of 28) of the EU Member States saw an improvement in reading skills during this period, with the most noticeable gains recorded in Ireland (where the share of 15 year-olds who were below level 2 fell by 7.1 points), Slovenia (6.1 points) and Spain (3.3 points). By contrast, the proportion of low-achievers went up at a rapid pace between 2009 and 2015 in Hungary and Slovakia (both reported increases of 9.9 points) and at a slightly slower pace in Greece (6.0 points).

Figure 14 presents a similar analysis with a focus on students who were below level 2 on the PISA mathematics scale. By this measure, more than one fifth (22.3 %) of the students aged 15 in the EU-28 were considered low-achievers in mathematics in 2015. Estonia, Finland and Denmark were the only EU Member States where the share of low-achievers in mathematics was already below the ET2020 target of (at most) 15 %. By contrast, the highest shares of low-achievers were recorded in Cyprus and Bulgaria (both over 40 %), while Romania, Greece and Croatia each reported shares within the range of 30-40 %.

As for low-achieving students in reading, there was little change in the share of students aged 15 in the EU-28 who were low-achievers in mathematics; between 2009 and 2015 this share fell from 22.6 % to 22.3 %. In Romania, Ireland, Bulgaria, Malta (2010-2015) and Slovenia, the share of low-achievers fell by 4-7 points. On the other hand, in Slovakia, Finland, Hungary and Greece, the proportion of low-achievers in mathematics increased by 5-7 points.

The final analysis in relation to PISA scores concerns low-achievers in science. The share of EU-28 students aged 15 who were below level 2 on the PISA science scale was just over one fifth (20.7 %) in 2015; this could be compared with 2009, when the proportion of low-achievers in science had been 2.7 points lower, at 18.0 %.

In 2015, Estonia and Finland were the only EU Member States that recorded shares of low-achieving students in science below the ET2020 target of (at most) 15 %. A majority (15 out of 28) of the Member States recorded shares of low-achievers in science that were above 20 %, rising to 37.9 % in Bulgaria, 38.5 % in Romania and peaking at 42.1 % in Cyprus.

Contrary to the other two subjects, there was a relatively clear pattern across the EU Member States with respect to developments for low-achievers in science. Between 2009 and 2015, the share of low-achievers rose in all but three of the Member States, with the proportion of low-achievers increasing by more than 10.0 points in both Hungary and Slovakia, while the share also rose by a considerable margin — within the range of 5.0-7.7 points — in Lithuania, Greece, Croatia, the Netherlands, Finland and Austria (2012-2015). The three Member States that reported a fall in their share of low-achievers in science were Denmark, Bulgaria and Romania.

The 2015 results from the PISA survey suggest that students from individual EU Member State tend to have similar skills levels for reading, mathematics and science; this may well be linked to the general organisation of education systems country-wide. There were relatively few low-achievers among students aged 15 in Denmark, Estonia, Ireland and Finland for all three disciplines: indeed, all four systematically appeared among the five Member States with the lowest shares for all three subjects, while Slovenia was also present in the five lowest low-achievers for mathematics and science (and had the sixth lowest rate for low-achievers in reading) and Poland completed the group of five lowest low-achievers for reading.

Early school leavers: situation improving in almost all EU Member States, especially for women

Secondary education is an important stage in an individual’s personal and professional development. Unfortunately, some young people leave the education system without the necessary skills that allow them to integrate successfully in the labour market. With this in mind, policymakers across the EU have sought measures that may help reduce the number of students leaving school or more generally education and training early. The Europe 2020 strategy is the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs: it emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and has set a target whereby the proportion of early leavers from education and training in the EU-28 should fall to less than 10 % by 2020. When transposing this strategy into individual plans, EU Member States set national targets reflecting their different starting positions and national circumstances.

WHO IS CONSIDERED AN EARLY LEAVER?

‘Early leavers from education and training’ refers to persons aged 18-24 years with at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment and who are no longer in education or training.

In 2016, the proportion of young people aged 18-24 years in the EU-28 who were considered as early leavers from education and training stood at 10.7 % (just above the Europe 2020 target of less than 10.0 %). There were 17 EU Member States where the share of young people who were early leavers from education and training was already below 10 %, while there were 15 where the latest rate met or was lower than the their national target (see Figure 16). The share of early leavers was particularly low in Croatia (2.8 %), Lithuania (4.8 %) and Slovenia (4.9 %). By contrast, the highest rates were observed in Malta (19.7 %), Spain (19.0 %) and Romania (18.5 %).

Although Malta and Spain recorded the highest rates among the EU Member States, they also recorded some of the biggest decreases in their respective shares of early leavers from education and training over the period between 2006 and 2016. The largest decrease (24.5 points) was recorded among early leavers from Portugal, with reductions of 12.5 points observed in Malta and 11.3 points in Spain. More generally, the share of early leavers fell in the vast majority of the Member States, with the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Romania the only exceptions as they reported a higher proportion of young people aged 18-24 years had left education and training with at most a lower secondary level of educational attainment in 2016 than in 2006.

On average, more young men (12.2 %) than young women (9.2 %) across the EU-28 left education and training early in 2016. This pattern was repeated in 25 out of the 28 EU Member States, with identical shares of early leavers in the Czech Republic and a slightly higher share for young women in Bulgaria and Romania. The most pronounced gender gaps — with shares for young men that were at least 6.0 points higher than those for young women — were recorded in Spain, Latvia, Cyprus (note the value for young women is of low reliability), Estonia, Portugal and Malta (see Figure 17).

Tertiary education: an increasing number of graduates, especially among women

Tertiary education (ISCED levels 5-8) — provided by universities and other higher education institutions, such as colleges and institutes of technology — plays a key role in knowledge-based societies. This is another area where a Europe 2020 target has been set by policymakers, namely, that by 2020 at least 40 % of the population aged 30-34 years should have a tertiary level of education. As with the indicator for early leavers from education and training, this target was transposed into national targets to reflect the specific situations of each EU Member State (see Figure 18).

Across the EU-28, in 2016 almost two fifths (39.1 %) of the population aged 30-34 years had completed a tertiary education (just 0.9 points below the Europe 2020 target).There were 18 EU Member States that reported that more than 40.0 % of people aged 30-34 years had a tertiary level of education, while 13 had already surpassed their national targets for 2020.

In 2016, more than half of all people aged 30-34 years had a tertiary level of educational attainment in Lithuania, Luxembourg (note this value is of low reliability), Cyprus, Ireland and Sweden. By contrast, there were 10 EU Member States where this share was below 40 %, among which the lowest levels of tertiary educational attainment were recorded in Romania, Italy, Croatia and Malta (all less than 30 %).

Compared with 2008, the share of people aged 30-34 years in the EU-28 with a tertiary level of educational attainment was 8.0 points higher in 2016. Spain was the only EU Member State to record a fall in its share, while the biggest increases — within the range of 15.0-19.0 points — were seen in Lithuania, Austria, the Czech Republic, Greece, Latvia and Slovakia.

The proportion of women aged 30-34 years with a tertiary level of educational attainment was higher than that recorded for men of the same age in all but one of the EU Member States (see Figure 19); the exception was Germany where the share of young men with a tertiary level of educational attainment was just 0.4 points higher than the corresponding rate for women. At the other end of the range, the largest gender gaps (with higher rates for women) were recorded in Latvia (26.0 points difference between the sexes), followed by Slovenia and Lithuania (where the difference was just over 20 points).

Quality of childcare and education

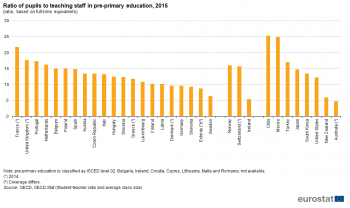

High-quality early education and childcare for young children is thought to improve their health and promote their development and learning. Indeed, high-quality, affordable care and pre-primary education coupled with after-school services are considered key aspects in this respect. Measuring the quality of formal childcare and education is difficult since there is no single indicator that adequately reflects the quality of the educational environment and the interaction between teachers and pupils. That said, a variety of different indicators may be employed to help form an opinion on developments, for example, average class sizes or child-to-staff ratios (where lower ratios may imply a better quality).

The ratio of pupils to teaching staff in pre-primary education (ISCED level 02) is shown in Figure 20. Based on the information that is available for 2015 (no data for seven of the EU Member States), pupil-to-teacher ratios ranged from 6.4 in Sweden and less than 10.0 pupils per member of teaching staff in Estonia (2014 data), Slovenia, Germany and Denmark (2014 data) up to 17.4 pupils per teacher in Portugal, 17.7 in the United Kingdom (2014 data) and peaked at 21.8 pupils per teacher in France (2014 data).

Figure 21 presents similar information for pupil-teacher ratios in primary and lower secondary education (as covered by ISCED levels 1 and 2). In 2015, the ratio of pupils to teachers across the EU-28 was somewhat higher in primary education (15.1 : 1) than it was for lower secondary education (12.6 : 1). This pattern was repeated in all but one of the EU Member States, with Luxembourg being the only exception with a higher ratio of pupils to teachers in lower secondary education (than in primary education).

Within primary education, the highest ratios of pupils to teachers were recorded in Romania, the Czech Republic, France, the United Kingdom and Bulgaria, where there were an average of 18 or 19 pupils per teacher in 2015. This was approximately twice as high as the ratio recorded in Greece (2014 data) which was the only EU Member State to report that it had an average of less than 10.0 pupils for every teacher within primary education.

In 2015, there were 11 EU Member States where the ratio of pupils to teachers in lower secondary education was lower than 10 : 1; the lowest ratio was recorded in Malta at 6.9 : 1. At the other end of the range, the highest ratios were recorded in the Netherlands (16.0 : 1), France (15.1 : 1), the United Kingdom (14.3 : 1) and Germany (13.3 : 1).

How much do the EU Member States spend on education?

A relatively strong link between educational expenditure and the performance of education sectors may be expected, whereby improvements in education systems are driven, at least in part, by increased investment in childcare, early childhood education and more general education services. Public expenditure on early childhood educational development and pre-primary education may provide support to families with young children participating in formal day-care services and/or pre-school institutions (including kindergartens and day-care centres). Most countries spend more on pre-primary education than they do on early childhood educational development, which probably reflects that the coverage of the former covers a larger number of children, while expenditure gradually increases as a function of higher levels of education.

Figure 22 shows that total public spending on early childhood education rarely accounted for more than 1.0 % of gross domestic product (GDP). Of the 26 EU Member States for which data are available in 2014, the total expenditure on early childhood education relative to GDP rose above 1.0 % in Sweden (1.8 %), Denmark, Finland and Bulgaria (all 1.1 %). At the other end of the range, there were six Member States where such expenditure was less than 0.5 % of GDP, the lowest ratios being recorded in the United Kingdom (0.2 %) and Ireland (0.1 %).

Figure 23 provides a similar analysis for pre-primary education, as well as other levels of school education: primary education and secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education on the other. In 2014, EU-28 public expenditure on primary education was 1.2 % of GDP, while spending on secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education was 2.2 %.

In 2014, total public expenditure on pre-primary, primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED levels 02-4) in the EU-28 was 3.9 % of GDP, a ratio that ranged from 5.0 % or more in Sweden, Denmark, Cyprus and Belgium, Denmark, down to 2.1 % in Romania.

Data sources and availability

Eurostat’s education statistics provide comparable information on key aspects of the education systems of the EU Member States. Data cover a range of different areas, including: enrolment and participation in education programmes by pupils and students, education and training outcomes, learning mobility among students, language learning, education personnel and expenditure on education.

One of the main sources of annual data on education is a joint questionnaire on education statistics that is overseen by the United Nations Institute for Statistics (UNESCO-UIS), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Eurostat; the data are compiled on the basis of national administrative sources, as reported by Ministries of education or national statistical offices. Commission Regulation (EU) No 912/2013 concerning the production and development of statistics on education and lifelong learning is the legal basis for these data from school year 2012/2013 onwards.

Data on formal and informal childcare are derived as secondary statistics from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC). Regulation (EC) No 1177/2013 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) provides the legal basis for the collection of these indicators. Statistics on educational attainment and early leavers are derived as secondary statistics from the EU’s Labour Force Survey (LFS). Council Regulation (EC) No 577/98 provides the legal basis for the organisation of a labour force sample survey across the EU; it provides a broad range of statistics on the labour market for both an annual and infra-annual periodicity which may be used, among others, to monitor the Europe 2020 strategy, the European employment strategy or economic and monetary policy in the EU.

Context

STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK — EDUCATION AND TRAINING 2020

The strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training 2020 (ET2020) was drawn up in 2009 with the aim of supporting EU Member States to develop their educational and training systems so that these encouraged all citizens to realise their full potential, by: making lifelong learning and mobility a reality; improving the quality and efficiency of education and training; promoting equity, social cohesion and active citizenship; enhancing creativity and innovation, including entrepreneurship.

In order to measure progress achieved on these objectives, the framework defines a set of targets to be achieved by 2020, namely:

- at least 95 % of children (from the age of four to the minimum compulsory school age) should participate in early childhood education;

- fewer than 15 % of 15-year-olds should be under-skilled in reading, mathematics and science;

- fewer than 10 % of young people aged 18-24 years should drop out of education and training;

- at least 40 % of people aged 30-34 years should have completed some form of higher education;

- at least 15 % of adults should participate in lifelong learning;

- at least 20 % of higher education graduates and 6 % of persons aged 18-34 years with an initial vocational qualification should have spent some time studying or training abroad;

- the share of employed graduates aged 20-34 years with at least an upper secondary level of educational attainment and having left education 1-3 years ago should be at least 82 %.

EUROPEAN STRATEGY FOR MULTILINGUALISM

At the 2002 Barcelona European Council, targets were set for the ‘mastery of basic skills, in particular by teaching at least two foreign languages from a very early age’. Since then, linguistic diversity has been encouraged throughout the EU, in the form of learning in schools, universities, adult education centres and company training.

The European Commission adopted in 2008 the Communication Multilingualism: an asset for Europe and a shared commitment (COM(2008) 566 final), which was followed by a Council Resolution on a European strategy for multilingualism (2008/C 320/01). Addressing multilingualism in the broader context of social cohesion and economic prosperity, the Communication urged the EU Member States to do more in order to achieve the Barcelona objective of enabling the citizens of the EU to communicate in two languages in addition to their mother tongue.

In 2014, these recommendations were endorsed in the Council Conclusions on multilingualism and the development of language competences which stated that EU Member States should assess and monitor progress in developing language competences in the national context; such assessments should cover all four language skills — reading, writing, listening and speaking. EU Member States agreed to adopt and improve measures aimed at promoting multilingualism from an early age and at enhancing the quality and efficiency of language learning and teaching.

See also

- All articles from the publication Being young in Europe today

- All articles on Education and training

Further Eurostat information

Main tables

- Participation in education and training (t_educ_part)

- Education and training outcomes (t_educ_outc)

- Living conditions (t_ilc_lv)

- Childcare arrangements (t_ilc_ca)

Database

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Education and training outcomes (educ_outc)

- Transition from education to work (edatt)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Childcare arrangements (ilc_ca)

- Youth education and training (yth_educ)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Education administrative data from 2013 onwards (ISCED 2011) (ESMS metadata file — educ_ueo_enr_esms)

- Educational attainment level and transition from education to work (based on EU-LFS) (ESMS metadata file — edat1_esms)

- Income and living conditions (ilc) (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

Other information

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 88/2011 of 2 February 2011 implementing Regulation (EC) No 452/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the production and development of statistics on education and lifelong learning, as regards statistics on education and training systems

- Communication from the Commission COM/2008/0566 final of 18 September 2008 on Multilingualism: an asset for Europe and a shared commitment

- Council conclusions 2014/C 183/06 of 20 May 2014 on multilingualism and the development of language competences

- Council Resolution 2008/C 320/01 of 21 November 2008 on a European strategy for multilingualism

- Presidency conclusions — Barcelona European Council, 15 and 16 March 2002

External links

- European Commission — Education and training monitor

- Eurydice — Key data on early childhood education and care in Europe, 2014

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — Education

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — Education at a glance 2017

- UNESCO — Education

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Notes

- ↑ OECD, Education at a glance, ‘Chapter C: Access to Education, Participation and Progression’, Paris, 2011.