- Data extracted in August 2017. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned update: May 2018.

International trade — especially the size and evolution of imports and exports — is an important indicator of a country’s economic performance, showing its status on the international stage.

This article takes a closer look at recent trends in the imports and exports of several of the world’s large economies, focusing on key trade statistics for goods and giving an insight into EU trading patterns compared to the world’s major economies. The article only deals with extra-EU trade, and does not consider trade between EU Member States (intra-EU trade).

(EUR billion)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_introle)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_introle)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_introle)

(EUR billion)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_introle)

(EUR billion)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_introle)

(EUR billion)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_introle)

(EUR billion)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_introle)

Main statistical findings

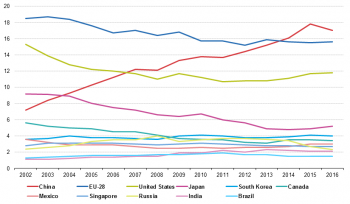

Main world traders: EU, USA and China

In 2016 the EU-28, the United States and China recorded by far the world’s highest trade values. Together, these countries accounted for 46.2 % of global exports of goods and 44.8 % of global imports. China recorded the world’s highest export values at EUR 1 895 billion followed by the EU and the United States, which recorded values of EUR 1 744 billion and EUR 1 515 billion respectively

(Figure 1).

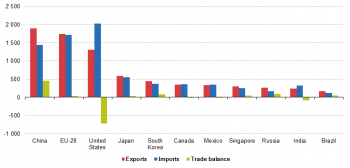

Looking at 2016 imports by value (see Figure 1), the United States had higher values (EUR 2 032 billion) than the EU (EUR 1 710 billion) and China (EUR 1 435 billion). The United States also recorded the highest trade deficit (EUR -517 billion), followed by India (EUR -87 billion) and Mexico (EUR -12 billion). The largest trade surpluses were recorded by China (EUR 460 billion) and Russia (EUR 93 billion).

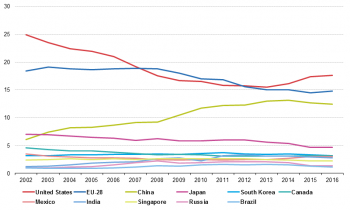

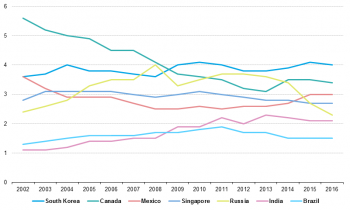

The United States has traditionally been a major trading economy but its relative significance has declined in recent years, particularly for exports. Between 2002 and 2011 the US share in total exports fell from 15.3 % to 12.0 % before climbing slowly to 13.6 % in 2016. (see Figure 2a). The steady growth of China’s trade has dramatically changed its role on the global market. Starting in the 4th position in 2002, it overtook Japan in 2004, the United States in 2008 and the EU in 2014. In 2016 its share of national exports in world exports was 17.0%, which was 1.4 points higher than that of the EU. The national export shares of the other countries are shown separately in Figure 2b to give some more detail.

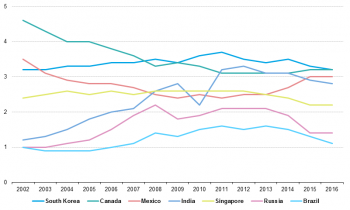

In contrast, China’s share in world imports has increased less quickly than its share in world exports, although in 2009 it exceeded 10 % for the first time and is now approaching the US and EU shares. The US share of world imports has fallen substantially from 2002 (24.9 %) to 2016 (17.6 %). The same holds true for the EU: although it was the world’s top importer from 2008 to 2011, the EU-28 was overtaken by the United States in 2012. China is the world’s third-largest importer; its share of world imports has largely been on the increase since 2008 (Figure 3a). The import shares of the other countries are shown separately in Figure 3b to give some more detail.

Evolution of EU trade over time

Over the last two decades, the EU grew from 12 to 28 Member States, thus increasing the size of its common market but also becoming a more important competitor on the world stage. The growth in EU trade, however, should not be considered as a mechanical effect of these enlargements; in fact, every enlargement increases the number of traders within the EU block, while reducing the number of partners outside the block.

The EU trade in such ’evolutionary’ terms has almost doubled since 2002. However, growth was interrupted twice in that period: once between 2000 and 2004 (a period marked by the bursting of the dot.com bubble) and again in 2009 (following the 2008 financial and economic crisis). In both cases, however, the economic downturns only delayed, without stopping, the expansion of global trade.

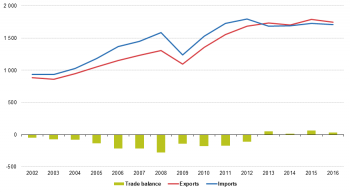

The EU trade in goods (both imports and exports) recovered after the rapid decline of 2009 (see Figure 4). However, in 2013 EU imports slowed down compared with 2012, while exports continued to grow, albeit gradually, resulting in a trade surplus (EUR 49 billion) for the first time since 2002. Between 2013 and 2015 exports continued to grow but fell slightly in 2016. Imports fell between 2012 and 2013 but then slowly picked up until 2015, before decreasing again in 2016. The resulting trade surplus peaked in 2015 at EUR 60 billion but fell to EUR 33 billion in 2016.

Trade by product group

Trade by product group in the EU-28

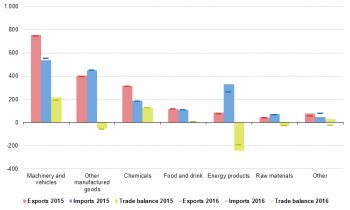

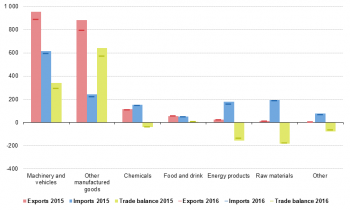

In the EU, trade surpluses in 'Machinery and vehicles' as well as 'Chemicals' tend to compensate deficits in other sectors, especially in 'Energy products', 'Other manufactured goods' and 'Raw materials' (see Figure 5). In 2016, 'Machinery and vehicles' were the EU’s most exported products (EUR 744 billion) and made up 43 % of total exports while 'Other manufactured goods' accounted for 23 % (EUR 396 billion) and 'Chemicals' for 18 % (EUR 314 billion). Thus the combined share of manufactured products (SITC 5–8) made up 83 % of total EU exports in 2016.

Manufactured goods also made up the majority of EU imports (69 %) in 2016, with the share of other imported manufactured goods only 3 % more to that of exports (see Figure 5). 'Machinery and vehicles' as well as 'Chemicals' accounted for smaller shares than the corresponding export values, with 32 % and 11 % respectively.

In 2016, the EU had a trade deficit in primary products and a trade surplus in manufactured products. The deficit in primary products was largely due to the deficit in 'Energy products' (EUR -190 billion) and to a lesser extent in 'Raw materials' (EUR -54 billion) while recording a small surplus in 'Food and drink' (EUR 7 billion) The surplus in manufactured goods came from 'Machinery and vehicles' (EUR 190 billion) and 'Chemicals' (EUR 128 billion) and was only slightly offset by 'Other manufactured goods' (EUR -54 billion).

Trade by product group in the United States

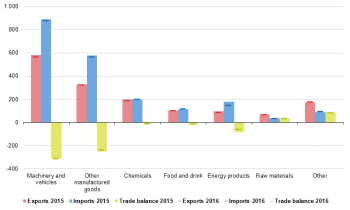

Unlike the EU, in 2016 the United States registered large trade deficits not only for 'Energy products' but also for 'Machinery and vehicle' and for 'Other manufactured products'(see Figure 6). 'Machinery and vehicles' made up the majority of US imports (EUR 876 billion) and exports (EUR 566 billion). This is also where the United States recorded its highest trade deficit (EUR -311 billion) followed by 'Other manufactured goods' (EUR -238 billion). 'Energy products' were ranked third (import values: EUR 148 billion; export values: EUR 86 billion) with a trade deficit of EUR -61 billion. The United States had low trade deficits in 'Food and drink' (EUR -162 billion) and in 'Chemicals' (EUR -11 billion).

The United States only registered trade surpluses for 'Other' (EUR 84 billion) and 'Raw materials' (EUR 36 billion). However, these values were not sufficient to compensate the deficits in the other product groups, resulting in a US trade deficit of EUR -537 billion in 2016. This deficit was EUR 20 billion less than that recorded in 2015 (EUR -517 billion).

Trade by product group in China

Almost 90 % of China’s exports in 2016 were concentrated in 'Machinery and vehicles' and 'Other manufactured goods' (EUR 889 billion and EUR 796 billion respectively - see Figure 7). China was also the world’s leading exporter in both sectors, just ahead of the EU for the first sector and with an export value higher than that of the EU and United States combined for the second sector.

China’s largest imports were also in 'Machinery and vehicles' (EUR 594 billion, 41 %) and 'Other manufactured goods' (EUR 224 billion, 16 %) . These were followed by 'Raw materials' (EUR 189 billion, 13 %), 'Energy products' (EUR 159 billion, 11 %) and 'Chemicals' (EUR 148 billion, 10 %). Imports in 'Other' (EUR 69 billion, 5 %) and in 'Food and drink' (EUR 50 billion, 3 %) were somewhat smaller.

As a result, China registered large trade surpluses in 'Machinery and vehicles' (EUR 295 billion) and especially in 'Other manufactured goods' (EUR 571 billion). The largest trade deficits were recorded for 'Raw materials' (EUR -177 billion) and 'Energy products' (EUR -135 billion). In 2016 China was the world’s leading importer of 'Raw materials' (it imported 90% more than the value of the EU and US combined) and the second largest importer of 'Energy products', behind the EU.

Data sources and availability

EU data is taken from Eurostat's COMEXT database. COMEXT is the reference database for international trade in goods. It provides access not only to both recent and historical data from the EU Member States but also to statistics of a significant number of third countries. International trade aggregated and detailed statistics disseminated via the Eurostat website are compiled from COMEXT data according to a monthly process.

Data are collected by the competent national authorities of the Member States and compiled according to a harmonised methodology established by EU regulations before transmission to Eurostat. For extra-EU trade, the statistical information is mainly provided by the traders on the basis of customs declarations.

EU data are compiled according to community guidelines and may, therefore, differ from national data published by the Member States. Statistics on extra-EU trade are calculated as the sum of trade of each of the 28 EU Member States with countries outside the EU. In other words, the EU is considered as a single trading entity and trade flows are measured into and out of the area, but not within it.

Data for the other major traders are taken from the Comtrade database of the United Nations. Data availability differs among countries, therefore Figure 1 shows the latest common available year for all the main traders. For the calculation of shares in Figures 2 and 3 the world trade is defined as the sum of EU trade with non-EU countries (source: Eurostat) plus the international trade of non-EU countries (source: IMF Dots database).

Methodology

According to the EU concept and definitions, extra-EU trade statistics (trade between EU Member States and non-EU countries) do not record exchanges involving goods in transit, placed in a customs warehouse or given temporary admission (for trade fairs, temporary exhibitions, tests, etc.). This is known as ‘special trade’. The partner is the country of final destination of the goods for exports and the country of origin for imports.

For more information see the EU-International trade data - Metadata page.

Product classification

Information on commodities exported and imported is presented according to the Standard international trade classification (SITC). A full description is available from Eurostat’s classification server RAMON.

Unit of measure

Trade values are expressed in billions (109) of euros. They correspond to the statistical value, i.e. to the amount which would be invoiced in case of sale or purchase at the national border of the reporting country. It is called a FOB value (free on board) for exports and a CIF value (cost, insurance, freight) for imports.

Context

Trade is an important indicator of Europe’s prosperity and place in the world. The block is deeply integrated into global markets both for the products it sources and the exports it sells. The EU trade policy is an important element of the external dimension of the ‘Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’ and is one of the main pillars of the EU’s relations with the rest of the world.

Because the 28 EU Member States share a single market and a single external border, they also have a single trade policy. EU Member States speak and negotiate collectively, both in the World Trade Organization, where the rules of international trade are agreed and enforced, and with individual trading partners. This common policy enables them to speak with one voice in trade negotiations, maximising their impact in such negotiations. This is even more important in a globalised world in which economies tend to cluster together in regional groups.

The openness of the EU’s trade regime has meant that the EU is the biggest player on the global trading scene and remains a good region to do business with. Thanks to the ease of modern transport and communications, it is now easier to produce, buy and sell goods around the world which gives European companies of every size the potential to trade outside Europe.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Data visualisation

Publications

Main tables

- International trade in goods (t_ext_go), see:

- International trade in goods - long-term indicators (t_ext_go_lti)

- International trade in goods - short-term indicators (t_ext_go_sti)

Database

- International trade in goods (ext_go), see:

- International trade in goods - aggregated data (ext_go_agg)

- International trade in goods - long-term indicators (ext_go_lti)

- International trade in goods - short-term indicators (ext_go_sti)

- International trade in goods - detailed data (detail)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- International trade in goods statistics - background

- International trade in goods (ESMS metadata file — ext_go_esms)

- User guide on European statistics on international trade in goods

Source data for figures (MS Excel)

External links

- European Commission

- United Nations

- World Bank