ACTION AND INACTION:

TWO SCENARIOS FOR 2030

2030 will be, of course, more than just two scenarios: it will be the result of our actions, and action is what foresight tries to generate. To illustrate the difference between action and inaction further, to bring it to life and make us understand the consequences of our (in)action more vividly, we outline the two extremes below. In reality, the future will in all likelihood not resemble one of these two, but lie somewhere in between.

IF WE TAKE ACTION

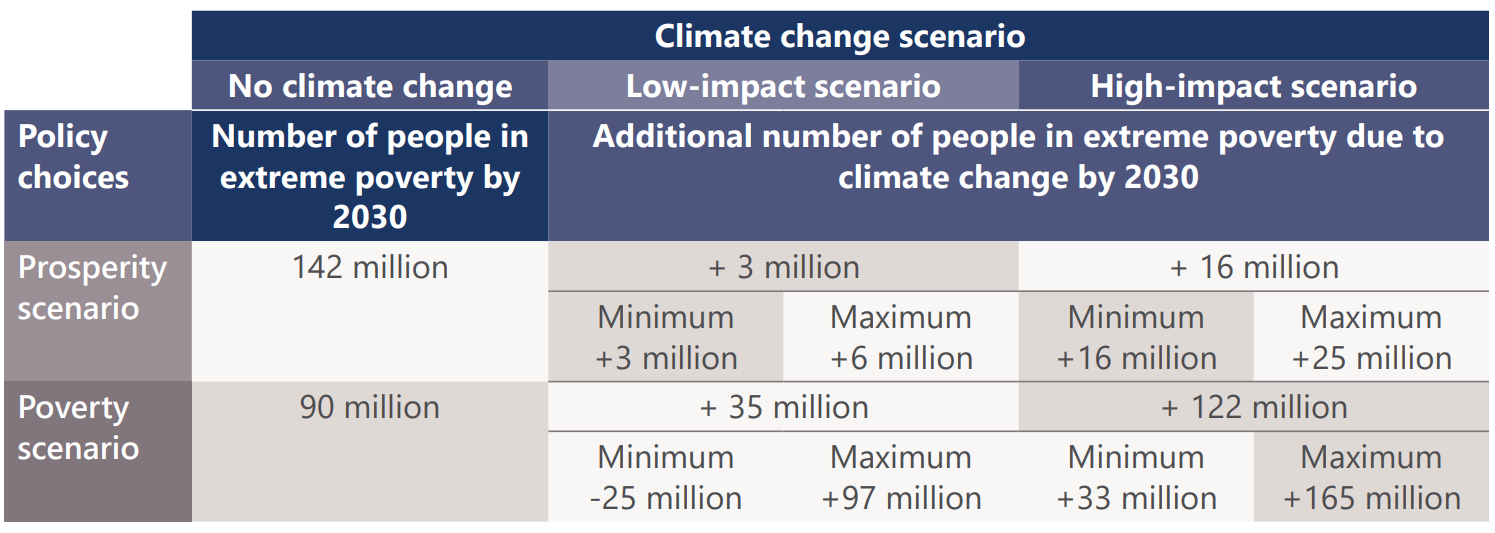

Climate change effects are diminished because states have taken more and faster action: temperatures rise but not more than 1.5 degrees. The EU, China and Japan join forces to mitigate the effects of American withdrawal from the Paris agreement. While in the short-term Europe has to accept a total GDP loss of $9–32 billion in this scenario, it is compensated by an increase in global importance, relational power and a leadership role beyond 2030 in transiting to a new, green economy.161 Policy decisions prevent 100 million people from falling into extreme poverty: preventive measures are taken against wildfires, reducing the impact of heat on less healthy persons and diminishing the anticipated costs.

A direct political gain is that an increasing share of clean energy in total energy consumption reduces European dependency on oil and gas imports from Russia and the Middle East, and contributes further to curbing greenhouse emissions alongside new technologies.

Europe prepares its labour force for the disruption caused by technological progress through training and education, easing not only the transition but generating new jobs in the process.162 Europeans finally take health-improving measures (such as 150 minutes of exercise per week, especially for those 60 years and older, and improve nutrition in older adults) and adapt work environments to the needs of older adults. Ageism is addressed, and older citizens continue to play a productive role in society.163 Policies are developed reducing the morbidity rate substantially: Europeans now spend 80% of their lives in good health (rather than 63% in 2018) thanks to moderate exercise and consistent nutrition. Due to a change in diet, Europeans not only lose weight, which boosts their health further – they also reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Artificial intelligence and big data are used to improve human lives. AI takes over repetitive human jobs, but humans remain in charge of the main jobs. Humans now steer artificial intelligence in support of their well-being. A common agreement on the use of autonomous machines in warfare, such as the one proposed by the United Nations Secretary General, ensures humans remain in charge of lethal decisions.164

Europe invests more in R&D and at last reaches its 3.0% target in 2020; this means it keeps pushing the technological frontier. Moreover, better cooperation between member states in the research field creates an environment that incentivises innovation.

Democracy recovers from its recent setbacks both in Europe and internationally: the stabilisation of Tunisia’s system, thanks to European support, proves to citizens in the broader region that democracy is beginning to make inroads in the Middle East and North Africa. In Europe, reduced rates of inequality, relatable political styles and positive economic developments mean that populist parties lose support. Regulated migration, assisted by integration programmes, reduces xenophobia and increases equality.

Violent conflict is mostly managed by a robust prevention programme developed by the United Nations; Europe is capable of defending itself in the real world and the cyber domain, making cyber-attacks much less effective. Thanks to increased cooperation within the Union, the EU develops a strong strategic degree of autonomy because it continues to invest in closer defence cooperation and capability development.

Europe reduces economic inequality by making it a policy priority. The measures taken include a stop to illicit outflows, labour abuses, and the creation of a minimum wage on the continent; abroad, the promotion of labour unions and increased inclusion of women in the labour force reduced inequalities and increased standards.

By installing an institutionalised foresight capacity, European leaders manage to anticipate and prepare for policy challenges – such as the loss of jobs due to automation.

At the global level, Europeans remain strong and cohesive, and build alliances with like-minded states across the globe. The EU cooperates with China and India (and other states) to maintain a globally connected economy and to mitigate climate change.

IF WE DO NOT TAKE ACTION

On climate change, states do not honour their commitments, meaning that the temperature rises by over two degrees. Record-breaking warm nights increase five-fold in Europe and costs multiply in several areas: healthcare costs increase as no provisions have been taken to mitigate the impact of heat on older adults; wildfires continue to spread; migration rates increase, and production is significantly reduced by droughts, floods and other extreme events. In addition, climate change pushes more than 100 million people into extreme poverty by 2030 – overturning the important progress made since the 1980s.165 A growing sense of impeding doom and panic undermines and divides societies, putting at risk our cooperative structures at all levels and stretching the EU's political stability to breaking point.

On longevity, Europeans continue to exercise little – costing EU countries €46.5 billion per year in healthcare. Malnutrition, social exclusion and inflexible work environments mean that older adults are not only excluded from the workplace, they increasingly fall ill, and place a significant burden on European healthcare and welfare systems.166

Unregulated advances in modern technology have unintended consequences. For instance, the use of robotics in warfare leads to indiscriminate killing; the unchecked evolution of superintelligence replaces human intelligence; big data is abused to undermine democracies and even free will. Jobs are lost without being replaced by new ones. Europe continues investing little in R&D and falls behind China in terms of innovation.

Continued support to ‘stabilocracies’ in the Western Balkans and the Middle East delays the emergence of stable democratic systems in these regions.

In Europe, unchecked inequality, flanked by large-scale loss of jobs as a result of technological progress, provides populist parties with ample pretexts to garner support. Lack of integration of migrants and continued terrorist attacks fuel xenophobia and empower populist parties further.

The absence of a functioning conflict resolution mechanism means that violence to Europe’s east and south continues to affect its security. Instead of steering conflicts positively, the Union is a passive bystander. In the military field, the EU remains fragmented and defensive, as well as vulnerable to asymmetric methods such as cyberattacks.

The income gap widens further, making the unequal distribution of income even more visible. Populist parties use this to their advantage in Europe; in the Middle East, it contributes to civil unrest.

At the international level, Europeans drift apart in a race for national sovereignty. The strength derived from their Union dissipates, diluting the European voice on the international stage. As a result, values such as democracy, human rights and peaceful resolution of conflict are eroded globally.

Footnotes:

- 161: Han-Cheng et al, ‘The impacts of U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on the carbon emission space and mitigation cost of China, EU, and Japan under the constraints of the global carbon emission space’, Advances in Climate Change Research, Volume 8, Issue 4, December 2017, pp.226-234

- 162: ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘Global Trends to 2030: New ways out of poverty and exclusion’, January 2019, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-new-ways-out-poverty-and-exclusion

- 163: World Health Organisation, ‘World report on Ageing and Health’, Geneva 2015, p.50 available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=4D697B6C455F69CB1A17C03DD5E6357B?sequence=1

- 164: United Nations, ‘Securing our common future: an agenda for disarmament’, New York, 2018, p.55, available at https://front.un-arm.org/documents/SG+disarmament+agenda_1.pdf

- 165: World Bank, ‘Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty’, Washington: 2016, available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/22787/9781464806735.pdf

- 166: World Health Organisation, ‘10 key facts on physical activity in the WHO European Region’, available at http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/physical-activity/data-and-statistics/10-key-facts-on-physical-activity-in-the-who-european-region