WELCOME TO 2030:

THE MEGA-TRENDS

Whenever we think about the future, mega-trends are our first helpers. This is because mega-trends have several characteristics in common that help us narrow down the futures from infinite possibilities to a restricted possibility space. As their name suggests, mega-trends are trends that occur on a large scale; they therefore affect large groups of humans, states, regions, and in many cases, the entire world. Mega-trends also unfold over an extended period of time: their lifespan is normally at least a decade, and often longer. Most importantly, mega-trends are linked to our present and are therefore phenomena we can already observe today. Because mega-trends are measurable, and affect many, and for a long period of time, they lend a previously foggy future an increased degree of visibility.

In this sense, mega-trends are the strategic forces that shape our future in a manner akin to a slowmoving glacier: they cannot easily be turned around by humans. In contrast to many other factors concerning the future, this type of trend can be backed up by verifiable data stretching into the past. The longer the data trail, the more reliable the trend.

Therefore, mega-trends serve as the backdrop against which any of Europe’s futures will be set in 2030.

However, while mega-trends present a high degree of measurability, they are still open to interpretation. This is where forecast is different from foresight: whereas the former establishes a future fact (e.g. the number of people who will have internet access), foresight interprets this fact (e.g. that this increased connectivity means international trade will become faster).

Climate change, demography, urbanisation, economic growth, energy consumption, connectivity and geopolitics are among the most prevaling mega-trends that are explored in this report.

WE ARE HOTTER

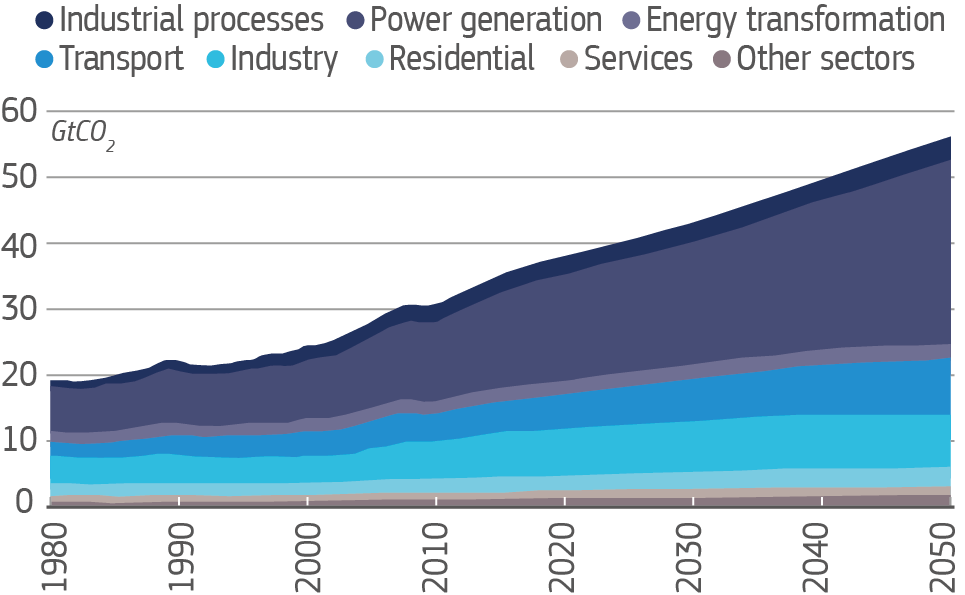

Climate change has two aspects to it: the dire consequences of past mistakes, which are already tangible today and will increase towards 2030, and the far worse consequences of mistakes we must avoid now. This means two things for the coming decade: first, that we will finally begin to feel the disruptive impact of rising temperatures and related weather events (the world is already 1 degree warmer than in the 1950s10), and second, that we may reach a tipping-point where changes to the climate become uncontrollable (discussed in the game-changers).

Concerning the first dimension, even in the unthinkable scenario of all emissions from human activities ceasing today, carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere will remain there for about 40 years. So irrespective of our next decisions, we will be hit by the fallout of past inaction and will have to manage the impact accordingly.

It is estimated that

By 2030, the world will be 1.5 degrees warmer than during pre-industrial times.11

This means that hotter summers will be the norm throughout Europe – but also in the United States, the southern neighbourhood and Asia. This will lead to increased occurrences of droughts and wildfires, as seen in the summer of 2018, the hottest on record and one in which 30-50% of certain key crops were lost in Europe. Studies show that healthcare costs increase significantly per heat wave, and that in the United States the cost of fighting wildfires reached $2 billion in 2017. In total, weather-climate disasters cost 290 billion euro in 2017.12

What does this mean?

- The increase in global temperature is the most pressing policy issue in the present day – and has been for the last decade, without generating the necessary responses.13 Today, the effects of global warming are beginning to be felt by the public and policymakers alike, triggering deep societal concerns. As a result, previously unpopular decisions which will curb emissions may become easier to take and implement. At the time of writing, our political systems are, however, not undergoing the necessary radical changes, increasing the risk of ‘runaway’ (i.e. uncontrollable) climate change up to 2030.

- An increase of 1.5 degrees is the maximum the planet can tolerate; should temperatures increase further beyond 2030, we will face even more droughts, floods, extreme heat and poverty for hundreds of millions of people; the likely demise of the most vulnerable populations – and at worst, the extinction of humankind altogether. Learn more about how we manage climate change.

- The main culprit for greenhouse gas emissions is energy production. By 2030, Europe is set to draw 32% of its energy from renewable energy sources – while we are a leader in this domain, it is not enough to curb temperatures.14 Learn more about energy.

- There are three actors in particular that are most responsible for the increase in emissions due to their sheer size, as well as for its future reduction: Europe, the United States and China. Only jointly can this challenge be met. Learn more about the future of multilateralism.

- Increased temperatures will be felt particularly in cities, making urban planning even more important. The larger the city, the larger the increase will be. Learn more about urbanisation.

- Extreme weather conditions, especially heat, hit older populations harder – which Europe will have more of. Learn more about demographics.

- Hotter temperatures will mean a drop in productivity – and even more emissions in a downward spiral thanks to air conditioning. By 2030, the loss in productivity due to the hotter climate will mean the loss of more than 1.7 trillion euros globally.15 Learn more about economics.

- Since high-level decision-making has not made the necessary progress, local and regional actors (such as the C40 initiative of 94 cities) have stepped in with their own measures in place to curb emissions. Learn more about urbanisation.

- Climate change is felt more in some places than in others: the Middle East and North Africa, for instance, will be afflicted by a temperature rise 1.5 times higher than the rest of the world. Aridification and extreme weather will push people from the countryside into cities and put pressure on existing conflict fault lines, as happened in Syria prior to the civil war.16 Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Rising emissions are linked to energy consumption and energy generation, which are projected to keep increasing in parallel with the growing global population and middle class. Learn more about demographics. Learn more about economics.

- Transport is another culprit for emissions – and one that will grow as mobility across the globe grows. Globally, green energy will clean up this sector only gradually and unevenly over the next decade. Learn more about connectivity.

- Cutting fuel subsidies and shifting to a greener economy is a painful step that can be exploited by populists worldwide. Learn more about populism.

- In part, climate change is driven by what we eat: 14.5% of greenhouse gas emissions result from livestock, especially cattle raised for both meat and milk.17 If cattle were a country, it would rank third in emissions behind the United States and China. What we eat is intrinsically connected not only to climate change, but also to how we age: the two issues must be addressed together. But at the moment, only a few states, such as Germany and Sweden, have developed dietary guidelines promoting environmentally sustainable diets. Learn more about how we age better.

WE ARE MORE, BUT WHERE?

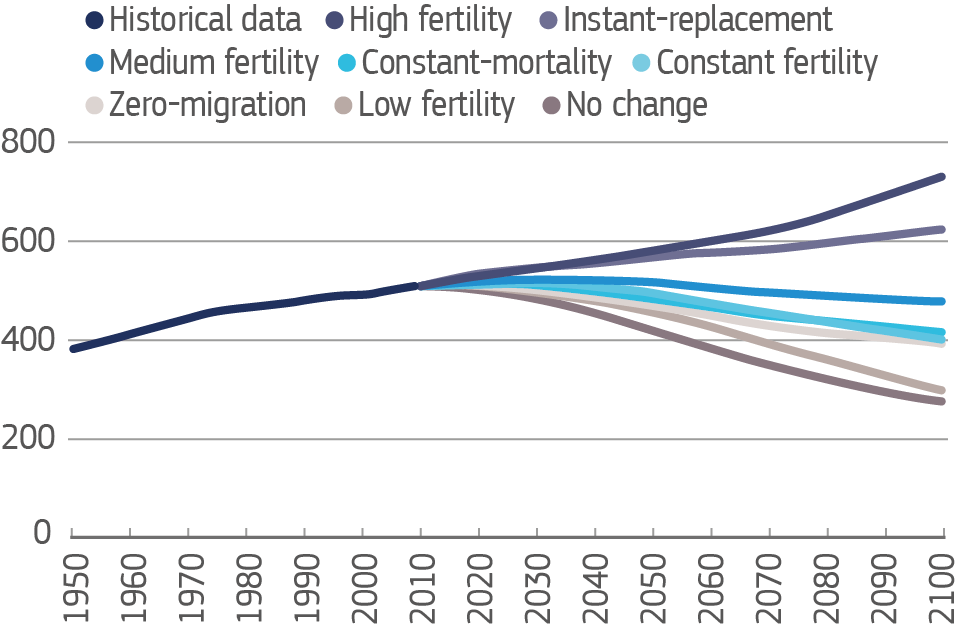

One of the best examples of a mega-trend is demographics. Because there are several decades between birth and death, the number of people living in a certain territory can normally be predicted with a higher degree of certainty.18 Therefore, while errors in mega-trend calculation can occur, they are normally not entirely off the mark. It is for this reason that we can say with plausible certainty that by 2030 the population of the world will be greater than today.

We will no longer be 7.6 billion, but 8.6 billion, in 2030.

To add some perspective to this impressive number, global population growth overall is slowing down – but it will not have stopped by 2030.19 As with projections generally, this number can change in a variety of ways, especially in the longer run due to uncertainties regarding the impact of climate change: for instance, because fertility rates do not develop as envisaged (in the past Asian rates dropped faster but African ones were slower than anticipated). But even pandemics, or drastic changes in fertility rates, are unlikely to change the 2030 figures significantly.

What is more interesting than the figure as such is, first, where this growth will occur, and second, and more importantly, the consequences.

Future demographics divide the world into two camps: one which is growing, and another which is shrinking. The first is, as is now common knowledge, the case in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Nigeria, Tanzania, Ethiopia, India, and Pakistan, for instance). Another region where growth will be substantial, of particular interest to the EU, will be the southern neighbourhood – Egypt alone will add 21 million inhabitants. Even though its growth is already slowing down and will continue to do so, regionally the trend will not yet be reversed by 2030 (only Tunisian and Lebanese fertility rates will then have reached European levels).

Europe’s southern neighbourhood will have reached 282 million in 2030 from 235 million today.

At the other end of the spectrum are those parts of the world where population size is stalling or decreasing – in the lead here is the European Union, whose population with 27 member states is projected to be anywhere between 498 and 529 million in 2030 (in 2018, it was 513.8 million, including the United Kingdom, and the possible increase will only materialise in a high-fertility scenario highly contingent on policies in this regard).20 But the EU is not alone: the eastern neighbourhood is following the same trend, and is likely to decrease from 74 million inhabitants today to 71 million in 2030.21 Russia, too, is projected to decline from 143.9 million to 140.5 million. Crucially, China has ‘peaked’ as well and will remain stable at about 1.4 billion. Overall, the populations of more than 50 countries will decline in the coming years.22

This trend is complemented by a second one: longevity. We are not only more numerous; globally, and in both ‘camps’, we also live longer. This is the result of a host of positive factors related to healthcare and wealth. By 2030, women in South Korea will have a life expectancy of 90, and in Africa life expectancy will be 64.23 In terms of longevity, European populations are already faring well and will continue to do so in 2030, when French women will reach the highest longevity in the EU with a life expectancy of 88.24

As a whole, the world will therefore be older than today: in 2030, 12% of the world population will be over 65, up from about 8% today.

Humanity is entering adulthood.

Europe leads this trend: in 2030, 25.5% of its population will be over 65 (up from 19% in 2017).25 Russia and China follow the same pattern, with one-quarter of their populations set to be over 60 in 2030 (although Russian life expectancy will continue to stay well below European averages).26 North America and Asia, especially India, will also see their populations live longer. But while humanity is growing older, some areas of the world will still feel the effects of youth bulges – whereby a population has a very high share of young adults and children. Even though numbers are dropping, they will remain high in Africa, but also in Europe’s southern neighbourhood where more than 45% are under the age of 30, down from 65% in 2010.27

What does this mean?

A look to the past shows us that demographics have been a source of anxiety ever since the 1970s, when the so-called ‘population explosion’ gave rise to the idea of an inevitable famine (some predictions even foresaw the end of humankind because of a lack of food).28 Global population increased, and the famine never materialised. Demographics today continue to be linked to other major concerns: from resources, climate and conflicts to migration, pensions, and health. As one report puts it: ‘demography is a political combat sport in which data and forecasts are weapons.’29 For Europeans, psychology plays a role, too: ‘decline’ sounds like a loss, and ‘growth’ elsewhere sounds a like fear-generating word. But what do these numbers actually imply for geopolitics, economics, and social issues?

- Europe’s work force will have shrunk by 2% in 2030 – despite the assumption that employment rates will slightly increase.30 Nevertheless, its GDP will continue to grow moderately. Learn more about economics.

- At the same time, European spending on agerelated issues will increase by 2%.31 Most of this will not be spent on pensions, but on health- and long-term care. This means that if we manage to improve how we age, we will be able to reduce these costs, work longer, and be happier. Learn more about how to improve ageing.

- A smaller Europe seems to imply less economic growth, but future economies will be less manpower-intensive. A smaller, and more educated population will be a competitive advantage – but at the moment, Europeans do not foresee an increase in educational spending. Learn more about how new technologies will shape future economies.

- Europe is not alone in facing the demographic challenge: China, Japan and Russia, too, have to find solutions for ageing populations and shrinking labour forces. Learn more about economics.

- Geopolitical influence is often seen as determined by population size – but this is a simplistic calculation. Influence is the result of economic performance, education, connectivity, relations and soft power – meaning that even given its comparatively smaller size, Europe can be an influential player. Learn more about multilateralism.

- Europe’s declining birth rate is, in part, a side effect of incomplete gender equality. Policies which would make it easier for mothers to work will have a positive impact on European demographics, economics, and equality. Although Europe is a leader in this regard, we are still far from the set goal: European women do more than twice the amount of domestic work, earn 16.2% less than their male colleagues, and display 10% lower employment rates than men.32 Several of Europe’s future demographic challenges will be much easier to handle when women and men are equal. Learn more about how to improve ageing.

- Population growth in Africa has led some to the assumption that these populations will ‘run out of space’ and move to Europe. Not only is Africa’s population density much lower than that of Europe or Asia, migration will be determined by several other factors rather than space. Learn more about migration.

- The solution to decline in birth rates seems to be migration, but past experiences with supplementing European economies with migrants shed some doubts on this assumption. As one expert concludes, ‘Despite the polemical assertions on both sides of the immigration debate, the evidence suggests that the net effects are usually likely to be small. (...) In the long term any economic effects are trivial.’33 Learn more about migration.

- Even though the southern neighbourhood’s youth bulge will have shrunk by 2030, it could still have destabilising effects in the region and Europe. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Rising temperatures will affect economic performance, and it will hit older people in the work force more. Learn more about climate change. Learn more about economics.

- There are concerns that older European populations will become more conservative and risk-averse politically speaking, but there is no evidence to prove this: rather than age alone, it is political events during the formative years of an individual that shape his or her voting behaviour.34 There is some hope that the longer humans live, the more educated they become as they accumulate knowledge – making them perhaps more critical when it comes to populist slogans. Learn more about populism.

WE LIVE IN CITIES

While urbanisation is one of the older trends discussed here (it emerged in the early 20th century in Europe and North America), it is now developing new characteristics. It is by now common knowledge that by 2030 two-thirds of the world will live in cities35, but it is often overlooked that

Far more will live in cities of under 1 million, followed by those between 1 and 5 million.

These small- to medium-sized cities are currently growing at twice the rate of megacities which dominate the discussion. But the number of megacities is not projected to increase significantly by 2030. Then, we will see 43 such agglomerations of more than 10 million people in the world (only one of which, Paris, will be located in the EU).36 Today, depending on how it is counted, there are already between 33 and 47 megacities on the planet.37 And even though they are and will be an important feature of 2030, they will be home to only 8% of the global urban population, whereas the rest will live in mediumsized cities – the future, while very much urban, will therefore be more Munich than Cairo in size and shape. While this sounds more manageable, it is also this type of medium-sized city, especially in Asia and Africa, which struggles to find the necessary capital to prepare for the challenges related to the coming growth.38

Europe’s levels and types of urbanisation are therefore very much in line with the rest of the world in 2030: most Europeans already live in cities between 100,000 and one million – and only 7% of the European population lives in cities larger than five million (compared to 25% in the United States), a trend that will remain the same in 2030.39 This means that

Cities, rather than megacities, are at the centre of all other trends discussed here.

Cities will consume 60-80% of energy resources, will be responsible for 70% of global emissions, account for 70% of the world gross domestic product and 35% of GDP growth. Cities are also where inequality and social exclusion are particularly pronounced, and where citizens interact chiefly with governance: while only 21% of Europeans declared to have faith in national governments, 45% declared to have faith in regional and city governments.40 Cities are the centre of innovation, of economic activity, but also the recipients of migration movements and the theatre for political discontent, conflict, terrorism and crime.41 Cities that offer attractive employment draw in an educated workforce from other parts of the country, contributing to salary segregation within a given country.42 When we say 2030 will be urban, this is not merely an expression of residency, it will be the way of life of society as a whole.

What does this mean?

Where urban growth occurs in an uncontrolled fashion, it leads to urban sprawl, low productivity, segregation, congestion and crime. That said, there are a number of reasons why a city is an attractive destination: on average, relocating to a city has improved the lives even of those living in dire circumstances – for example, by allowing for better access to water and electricity.43 This means that the city should be understood not merely as a hotbed of problems, but as a potential accelerator of human progress – if managed properly.

- In 2030, local politics will be the conveyor belt for other policy issues: already, European regional and local elections match national elections in voter turnout. This means that cities are much closer to the daily lives and grievances of citizens, and therefore powerful antidotes to populist movements thriving on the perceived distance between the electorate and the national governments. This could also help address the democratic deficit often raised with regard to the EU.44 Learn more about populism.

- This is the case elsewhere, too: in Libya and Ukraine, conflict resolution has been most successful at the local level. European cities assisted in conflict settlement, opening avenues for a new model of the ‘diplomacity’, a new actor in diplomacy. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Terrorism is an urban phenomenon, but cities are rarely involved in the decision-making which addresses it.45 Learn more about terrorism.

- Urbanisation correlates with declining fertility rates, suggesting potentially lower birth rates in the future, as states in Africa urbanise, too. Learn more about demographics.

- Cities are considered responsible for increased pollution and climate change – but it is not human agglomeration itself that is the main culprit, but several other factors such as how well the city is connected, how large households are, what the population’s median age is, how many industries are located within the city and how densely the city is populated. In fact, higher population density can lead to less energy consumption and emissions when transport and buildings are suitably adapted.46 Learn more about how we tackle climate change. Learn more about the effects of climate change.

- Modern technology has the potential to change urban areas into cleaner, safer and more efficient places, so-called ‘smart cities’ – provided there is connectivity and a minimum of infrastructure development. Learn more about connectivity. Learn more about new technologies. Learn more about how we could manage technological progress.

- Cities are associated with crime, but urbanisation is not the only relevant variable. Instead, urban crime heavily correlates with unemployment, inequality and inflation. Learn more about economics.

- Cities are also considered responsible for rising inequality – but it is there that inequality is decreasing faster than elsewhere.47 Learn more about economics.

- Only one European city, Frankfurt, appeared in the top 20 of unequal cities.48 Learn more about economics.

- Rapid urbanisation is correlated with the outbreak of civil war: as grievances over inadequate housing and jobs accumulate, networks of discontent and crime do, too. That said, few states concerned by emerging megacities (especially in Africa and Asia) have plans to manage the speed of their development – or struggle to find the necessary funds.49 Learn more about conflicts to come. Learn more about how we manage those conflicts.

- Even though crime is more frequent in cities than in rural areas, violent crime as a whole has been on the decline globally since the 1990s.50 The new type of crime now is organised – and digital. Learn more about connectivity.

- Military action will see more urban warfare than before as a result of more people living in cities. But not all armed forces are prepared for this type of combat which requires a different type of skill from currently common warfare – with potentially large scale destruction of infrastructure and many victims as a result, as happened in Syria. Learn more about conflicts to come.

WE CONTINUE TO GROW ECONOMICALLY

At first glance, prospects for the global economy look rather positive: projections show that average global economic growth will be around 3% a year in the coming decade, making the world a richer place than today.51 Most of this growth will happen in the developing economies, whose growth will accelerate from 3.1% currently to 3.6%. Developed economies, too, will grow, albeit at a much slower rate: Europe, for instance, is projected to grow at 1.4% a year – this could still fail to improve employment rates, investment levels and the integration of young people into the labour market.52

Taken together, these two developments mean that in 2030, China is expected to become the world’s largest economy, surpassing the United States. As a result,

Europe will be the third global economy.

It is worth noting that things look quite different when measured as GDP per capita: while China’s will grow from currently $10,000 to $14,000 in 2030, Europe’s GDP per capita is expected to grow from $37,800 to around $50,950.53

These projections are, however, not fail-safe: while measures have been taken to prevent another financial crisis, there are still some elements policymakers should be concerned about. For instance, public debt remains high, financial regulatory reform is not yet complete, and global tensions over trade could destabilise the global economy.54 And economic growth could slow down in China and the United States, affecting Europe as well.

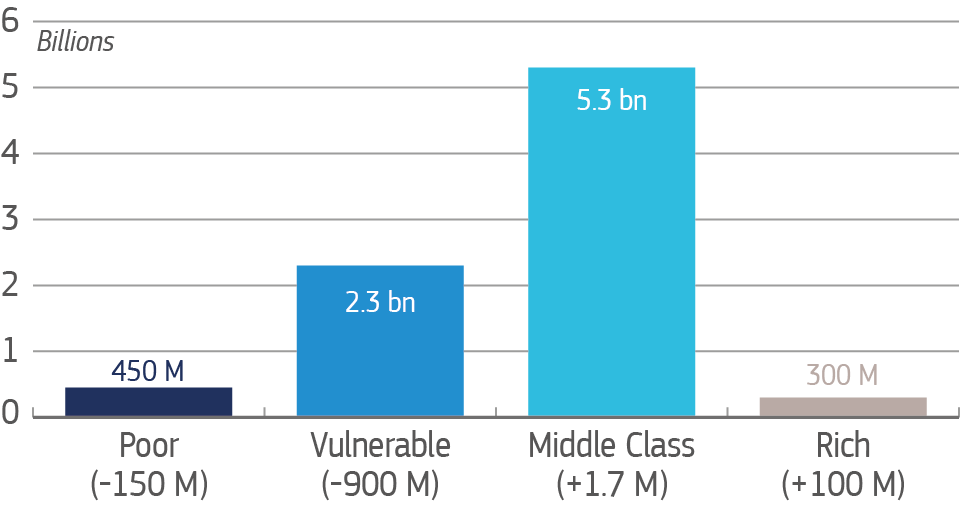

Two rather positive dynamics are the result of these global developments: first, by 2030 the majority of the world will be middle class – defined as individuals falling anywhere between 67-200% of the median income in a country. Current estimates show that there will be 5.3 billion people classified as such in 2030, up from 3.2 billion now.55 A large chunk of these people will be situated in emerging economies, especially in China. In addition, extreme poverty – defined as living on less than $1.90 a day – now stands at 10.9%, down from 35% in 1990 – as the goal of cutting the 1990 poverty rate in half was reached five years ahead of schedule, in 2010. This means that the goal of reducing the rate to 3% in 2030 is a realistic one.56

Second, while almost everybody will be doing better in 2030, so will those that are already doing best – 1% of the world’s population is projected to own two-thirds of its wealth in 2030, up from half of what it owns today.57 This is hardly a new trend: the phenomenon of wealth accumulation has been three decades in the making. That said, there are critical differences from country to country – for instance, Europe is home to the most equal societies, but inequality is very pronounced in the United States or the southern part of Africa. In general, inequality within countries is more pronounced than between countries.

How inequality emerges, and indeed increases, is still a puzzle. While it is related to differences in salaries, this is not all there is – other factors are the uneven accumulation of wealth over time, a general shift from low- to high-skill work, a decline in labour market protection, and tax policies.58 Somewhat ironically, it is even the result of improved gender equality: as educated men increasingly marry educated women (a phenomenon called ‘assortative mating’), female social mobility is reduced.59 Globalisation has also been accused of promoting inequality, but not all evidence supports this claim. Simply put: inequality of household income is the result of several interlinked dynamics which are not easily untangled.

In addition, there is a somewhat paradoxical dimension to it, at least in Europe: the feeling of inequality may well intensify in societies that are approaching a high level of economic well-being. This is because in highly unequal societies, every new generation in the bottom income share will see its status improve over time. In equal societies, however, this improvement is obviously no longer as visible. And in Europe a 50-year trend towards poverty reduction is paying off – we are already very equal, meaning a perception of stagnation is setting in.

Future generations will not feel better off than their parents, but they will still be well off.

In fact, never has the world, and especially Europe, had as much as today. The poor still have less than the rich, of course, but it does not necessarily mean that they have next to nothing. But the problem with this is essentially philosophical one: a sense of progress is almost more important to humans than an absolute sense of well-being. This means that inequality is not merely an economic problem: it is part of a larger complex issue which also includes poverty, slow economic growth, social exclusion, access to essential services, and mental health. It is worth noting that while European poverty differs from poverty elsewhere in that we are wealthier than most of the rest of the world, 23.4% of our population is still at risk of poverty, living of 60% or less of the national median income. This number has remained more or less the same over the last 15 years.60

In that sense, slowing economic growth and increasing inequality lead to a larger question which goes beyond income: what can be done to improve European happiness in the absence of economic miracles seemingly out of reach in a service-based economy? This is not a naïve question, quite the contrary. After all, “the care of human life and happiness ... is the only legitimate object of good government”61, as Thomas Jefferson put it. Human happiness revolves around essentially six ingredients, according to the United Nations: GDP per capita, healthy years of life expectancy, social support (as measured by having someone to count on in times of trouble), trust (as measured by a perceived absence of corruption in government and business), perceived freedom to make life decisions, and generosity (as measured by recent donations).62 This attempt to gauge happiness acknowledges that economic prosperity and good health and social services play a central role. It is no coincidence that the UN Happiness Report finds that Europe is already one of the happiest places on Earth – but this does not mean that there is no discontent. In fact, the report finds that mental illness impacts European happiness as much as (if not more than) income, employment or physical illness.

But while economic factors are not the only – or indeed the most important – factors in determining human satisfaction with life, neither mental well-being, nor social connectivity have a prominent place on policymakers’ agendas.63 Therefore, in addition to addressing legitimate economic concerns, policymakers could take a step back and address the broader question of human well-being beyond economic terms – and thereby achieve the necessary shift which is key to Europe developing any alternative to high-growth, high-consumption economic models, which may be quashed by climate change consequences.64

What does this mean?

Economics is at the centre of human activity: areas such as the environment, security, education, political stability and even health are all connected to economic development. But it is precisely because of their interconnected nature that it is so hard to anticipate certain economic developments, such as the 2008 financial crisis. That said, because economics is largely in the hands of humans, it is here where decisions normally have rather quick effects – both negative and positive.

- Switching to a low-carbon, climate-neutral, resource-efficient and biodiverse economy will not only be beneficial for our employment rates and growth – it will also help us tackle climate change and other environmental challenges. Learn more about how we manage climate change.

- Some studies say that the advances made in poverty reduction might be overturned by climate change, pushing more than 100 million people into extreme poverty by 2030.65 Learn more about how we will manage climate change.

- A growing middle class will have the means available to consume more energy – in Asia and Africa, this will mean fossil fuel. Learn more about energy.

- Contrary to the common idea that poverty pushes people to cross international borders, it is in fact a rise in income that does this; job creation for the rising African middle class is therefore a priority. Learn more about migration.

- Inequality correlates more with the outbreak of civil unrest than poverty.66 Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Reducing inequality by increasing wages will have several positive effects, including on our pension and healthcare system. Learn more about how we improve ageing.

- Emerging markets will only realise their full economic potential if they implement reforms and improve their institutions – more so than Europe, they are at risk of a financial crisis. This means substantive investment in education, infrastructure and technology. Learn more about new technologies. Learn more about connectivity.

- A growing middle class is also likely to have political expectations that will need to be met, but it will not on itself be the ‘grand democratiser’ of non-democratic societies. Learn more about how to protect democracy. Learn more about populism.

- Economic growth also depends on a stable global trade regime, something which is currently under stress. Learn more about the future of trade.

- Economic growth and job creation are not an end in themselves: hyper-connectivity in the workplace will make people (including decisionmakers) increasingly unhappy, which, in turn, lowers productivity and damages health.67 Learn more about connectivity.

- Western labour markets are heading towards disruption thanks to technological innovation, but it is not clear how many jobs are threatened – or will be created. Learn more about new technologies.

- Innovation and ideas will be the key feature of the next leading economies – and education will be key to this. Learn more about new technologies.

- For Europe, most of its growth potential lies in services and the digital realm – but the extent of this depends on how fast it manages to catch up with other states. If the EU wants to stay competitive, it will have to increase its investment in research and development (R&D) from 2.03% of GDP currently to 3%.68 (The current figure is lower than in Japan (3.29%), the United States (2.79%), and China (2.07%)). Learn more about new technologies. Learn more about trade.

- Even though Europe is home to the most equal societies, inequality is an issue policymakers have to address, or populists will. Social measures such as a minimum wage, or a basic income, are one way to address the issue – and will, according to an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) study, have a neutral or even positive effect on growth.69 Learn more about populism.

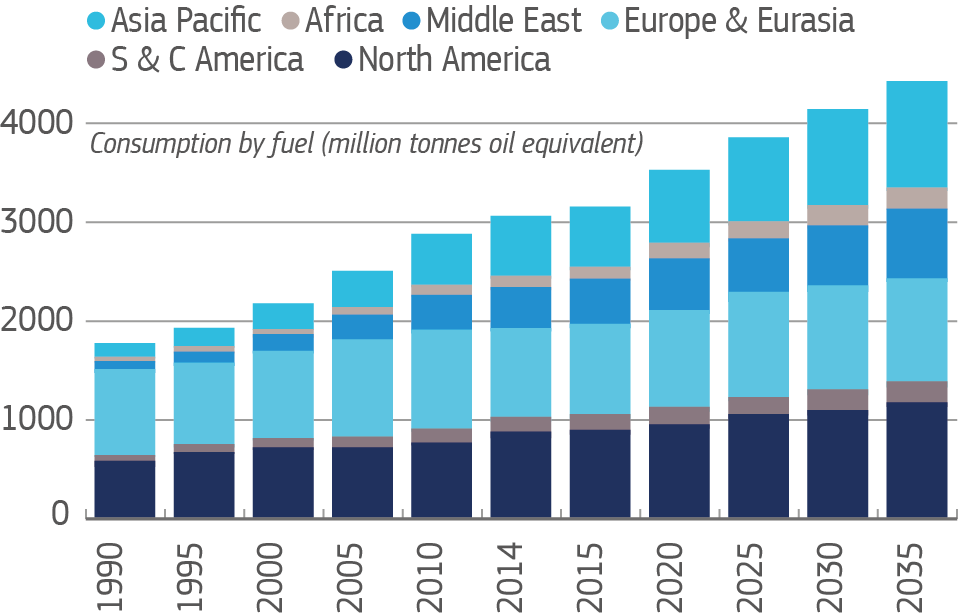

WE NEED MORE ENERGY

Energy is a good example of two mega-trends joining up: because we will be more in number, and because we have more income available to spend,

Energy consumption will rise globally by 1.7% per year

– approximately the same speed as it rose between 1970 and 1990. This is not a European phenomenon: although demand will also increase in Europe and other Western states, it will mainly grow in non-OECD states – particularly India and China. As a result, oil, gas and coal prices will increase continuously, but not dramatically in the years up to 2030, returning to the high levels of 2010.70

Due to global shifts away from industrial to serviceoriented economies, global oil demand is expected to decelerate sometime after 2040, but oil, coal and gas will continue to meet most of the world’s energy demands – mainly because renewable energy sources will not yet be able to meet the global demand. While Europe is in the lead in the energy transition, it will not have completed it by 2030. Its own goal is to then draw 32% of its energy from renewable sources. This means that its energy import dependency, especially with regards to gas, will slightly increase by 2030.71 The United States will approach energy independence by then.

What does this mean?

The fact that other world regions will consume more energy is often labelled as ‘energy competition’; the term suggests resource scarcity, and that Europe may not be able to meet its needs on the global market – but this is a finite understanding of energy. Already, about half of Europe’s energy is renewable, and oil and gas reserves mean that by 2030 energy will be available at reasonable prices. That said, increased energy consumption may have several other knock-on effects that are worrying – or encouraging.

- Energy production is already the largest source of global greenhouse-gas emissions – the main driver behind climate change. With increasing needs for energy, the pressure on curbing the effects of climate change increases even further. Learn more about climate change.

- ‘Green’ energies have promising prospects for job creation, making them a future asset of our economies. Learn more about economic growth.

- At a time of increased international antagonism, aggressive competition for resources could become a source of rivalry among states regardless of the fact that there is no critical scarcity. Learn more about geopolitics.

- The development of new energy sources opens up the possibility of international partnerships on renewable energy development, potentially decreasing the importance of fossil fuel dependency.72 Learn more about how we manage climate change.

- Energy efficiency is improving and diversification continues, which could change projections for 2030. For instance, energy storage is projected to increase six fold in the coming decade, enabling renewable energy and electric cars.73 Learn more about new technologies.

- Rising energy needs in non-OECD countries are a side effect of rapid motorisation: the global passenger car stock is set to nearly double between 2012 and 2030 (whereas it will decrease in Europe). This has effects on economic, political and social connectivity. Learn more about connectivity.

WE ARE HIGHLY CONNECTED

The planet will continue to feel ever smaller in 2030: not only are more people able to communicate over the internet (90% of the world population will be able to read; 75% will have mobile connectivity; 60% should have broadband access), they will also move more.74 Connectivity is therefore not only virtual and digital, but also physical.

The internet will be in our cars, homeware, and even on our bodies.

By 2030, the number of devices connected to the internet will have reached 125 billion, up from 27 billion in 2017.

Almost all European cars will be connected to the internet in 2030, making our roads even safer.75 Air travel will be safer, too – 2017 was the safest year in aviation history, although our skies have never been so busy.

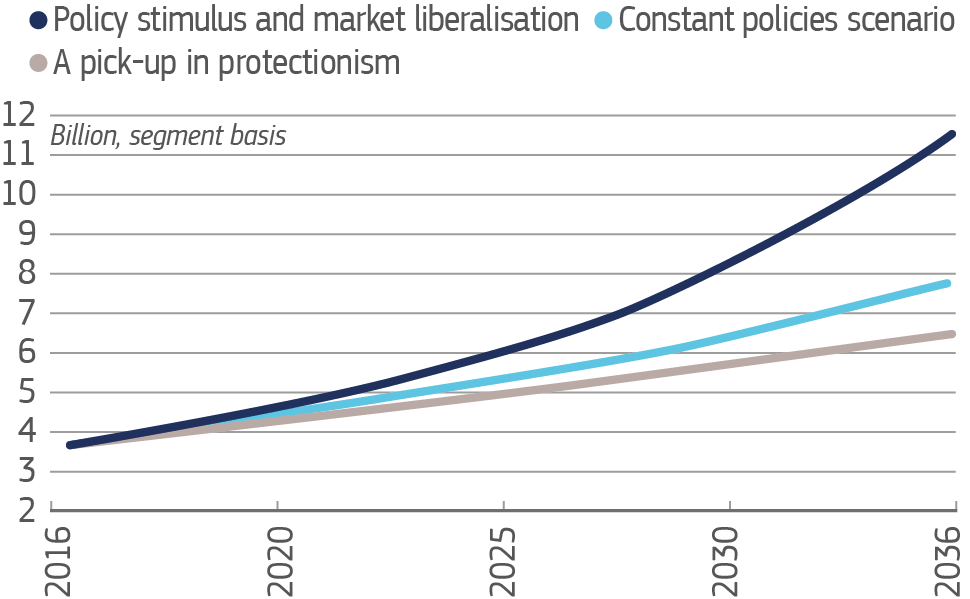

Because humans are connected not only online but also through improved infrastructure, they and the goods they trade will move more than today: by 2030, air passenger numbers will have nearly doubled to more than 7 billion – most of which will be from the Asian middle class.76 Air freight will triple and port handling of maritime containers worldwide could quadruple by 2030.77

Land transport, too, will be affected: while private car ownership is projected to decrease in Europe and the United States, alternative options for transport – such as shared cars – will be on the rise.78 Elsewhere, car sales will continue to increase. For instance, by 2030, China will have 50% more cars than today. Some studies expect about half of new cars to be electric in 2030. Trains will also be an area of innovation: super high-speed trains (such as Hyperloop) can reduce travel time by nearly 90% and lower environmental damage. And as humans travel, so do the diseases they carry, increasing the risk of pandemics. While there has been progress on prevention and reporting, especially vulnerable states are lagging behind when it comes to important reforms in this regard.79 (But it is worth noting that no pandemic ever managed to wipe out more than 6% of the world population, despite the fact that they occur regularly.)

What does this mean?

Connectivity, like other mega-trends, is in itself neither positive nor negative, but in fact both. It acts as a multiplier of human behaviour more than anything else. In this sense, any human pattern, whether detrimental or beneficial, will be strengthened by connectivity. This also means that we have a certain degree of predictability, as we have some certainties about human behaviour. For instance, because human beings like communication, we can ascertain that any device facilitating it will be embraced enthusiastically. Social media, for instance, must be understood not as a static set of providers, such as Facebook or Twitter, but as evolving networks reflecting the state of mind of humanity at this point in time.

- In some ways, connectivity has a negative impact on the environment, air travel and shipping, for instance. Improved aircrafts, operational efficiency, and alternative fuels can reduce this impact.80 Learn more about how to prevent climate change. Learn more about new technologies.

- Connectivity is one of the drivers of a more pluralistic world. Learn more about geopolitics.

- Modern technology, especially artificial intelligence (AI), can make airport experiences smoother and faster, increasing the travel volume even further – assuming trade and/or visa liberalisation continue. Learn more about new technologies. Learn more about trade.

- Modern technology can help address the employment needs of modern connectivity: for instance, by 2030 the commercial aviation industry will require three times as many pilots as today. Technology can help fill this need. Learn more about new technologies.

- Human life in cities can be improved through connectivity: traffic, waste management, transport and even crime can be addressed better through connection to the internet.81 Learn more about urbanisation.

- Information, especially news, will be drawn mainly from the internet, with fake news, slander and potential for polarisation and election meddling increasing. Emotions in communication will become more and more important as the distance between citizens and decision-makers shrinks. Learn more about how we protect democracy in Europe.

- Connectivity means that individuals can identify with global policy issues beyond their borders, creating clusters of online citizenship. This could, or could not, be vulnerable to manipulation.82 Learn more about how we protect democracy in Europe.

- As information travels much faster, reactions to certain policy issues will be more intense and concentrated. This puts decision-makers under pressure to act without the necessary time for reflection and consideration. Institutionalising longer-term strategic thinking units will be key to avoid short-termism under stress. Learn more about populism. Learn more about how we protect democracy in Europe.

- Connectivity can also mean vulnerability: cyberspace will be one of the battlegrounds where states and non-state actors confront each other. Learn more about conflicts to come. Learn more about how we deal with conflict.

- To achieve the maximum benefit from connectivity, most artificial intelligence systems will require access to big data – something many European citizens are uncomfortable with. Learn more about how we deal with the challenges of new technology.

- Connectivity means that irregular migrants learn quickly about European policies and adjust to them. Learn more about migration.

WE ARE POLY-NODAL

Many analysts have already proclaimed the advent of multipolarity. They are overhasty: in fact, we are only just beginning to transit out of the post 1990 unipolar system. The uncertainty of the geopolitical future is a frightening thought, causing worst-case scenario thinking in which NATO no longer exists, nationalistic states form unstable alliances, China dominates the rest of the world, and war becomes a distinct possibility. Indeed, some of the phenomena we see today, be it populism or protectionism, are direct consequences of this uncertainty.

And yet, it is helpful to add to the uncertainty and ask one more important question: are we actually heading for a multipolar order in the neorealist sense of the word? After all, it is doubtful that the world will be structured around ‘poles’ (that is: cohesive centres of power). 2030 will not just be different in terms of power distribution, but also in terms of the nature of power itself. Power will not be determined solely by classic measures such as population size, GDP and military spending, and it will be held not just by states, but also by cities, regions, companies and transnational movements. The connectivity, interdependence and pluralistic nature of the system will mean that

The power of states will be determined by their relational influence.

In that sense, it is not ‘poles’ that will be the building blocks of the system but ‘nodes’: points where pathways relate to each other. This is because in the future, no single state will be able to tackle major global challenges alone. As a result, a state’s importance will depend on its capacity to deploy a variety of mechanisms to influence the policy decisions of other states, rather than just on the raw capabilities it has at its disposal. The key determinants for this will be the number and quality of bi- and multilateral relationships. Influence will be determined by trade and aid flows rather than economic power, and by arms and technology transfers rather than military spending. In a similar vein, membership of international organisations and alliances will constitute capital, as will connectivity – especially in the form of new technologies. Soft power and the ability to inspire others will also increase in importance.83 This means that values will not go out of style, and states with shared ones will continue to gravitate towards each other.

Contrary to popular belief, pluralistic systems are not less stable than bipolar ones: the father of classical realism, Hans Morgenthau, was convinced that plural systems would generate greater stability because the defection of a single state from an alliance would not upset the whole system. Yet much akin to the bipolar system, because states would have to rely on allies to maintain stability, they would act cautiously in order to not upset the balance. Moreover, largescale wars could be avoided as gains can be made through alliances.84

That said, should this structure emerge, it will be shaped by the future trajectory of a number of geopolitical relationships. Of paramount importance will be the evolution of relations between the United States and China – but also between Beijing and the rest of the world. Despite its great power ambitions for 2050, China will also have to contend with the pluralistic nature of global affairs – if it continues on its current neorealist path to power, China will struggle to build positive relationships with its immediate neighbours, Europe, and, of course, the United States.

But Europe will have to adapt to this new pluralistic system, too. This means redefining the transatlantic relationship, both with its organisational embodiment, NATO, and the United States itself. In this context, it is important to note that although certain voices in the United States have openly questioned the usefulness of the alliance, American actions have been consistently supportive of it – quadrupling the financial support to eastern European member states, for instance, as well as increasing its presence on what NATO refers to as the ‘Eastern front’. As one observer put it, ‘Despite concerns about the future course of the Trump administration, NATO is significantly stronger today than five years ago, when it was looking for a new raison d’être.’85 That said, American engagement in NATO will remain strong only as long as Russia is perceived as a threat – a perception which is dwindling as Moscow is seen as being in decline and Beijing on the rise. Precisely because Europe does not collectively share this assessment, this means that

Strategic autonomy is no longer a mere option for Europe.

This is the case for two main reasons. First, if Europe wishes to remain a close ally of the United States it will have to be able to support Washington’s power projection in Asia (and elsewhere). Second, and even if it chooses not to support the United States there, it will have to fill the security vacuum the American pivot to Asia will leave behind by fully providing for its own security – within and outside of NATO.86

Lastly, the plural nature of the system does not mean that its natural form of governance will be ‘multilateral’ as the term is understood today. That said, once current multilateral institutions have reformed and adapted to the new pluralistic power distribution, they will remain the most important frameworks for interaction: the more players, the more important they will be.87

What does this mean?

In international relations, interdependence has been interpreted since the 1970s as a motivation for cooperation rather than antagonism (captured in the expression ‘where goods don’t cross borders, soldiers will’).88 Alas, interdependence and the relational nature of power have not meant, and will not mean in 2030, that conflict and competition will be a thing of the past. Instead, a connected system will mean mainly a new understanding of global politics and power.

A few things to consider are:

- The multilateral nature of the EU means it is well equipped for the shift in power perception described above – but it is crucial that it futureproofs itself, and the multilateral institutions it cares about. Learn more about how we navigate this system.

- Because of the uncertainty generated by the transition of power, conflict remains not only a possibility, but a likely feature of the decade unfolding ahead of us. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- How Europe is equipped for these conflicts depends very much on how it prepares for them. Learn more about how we manage conflict.

- The main feature of the world of 2030 will be its connected nature – defining everything, including geopolitics. Learn more about connectivity.

- Power will also be determined by the extent to which states are leaders in new technologies – an area where the United States and China are in the lead, and Europe is lagging behind. Learn more about how we manage new technologies.

- How citizens feel about their state’s role in the world feeds into their identity – indeed, there is a link between populism and perceived loss of global importance.89 Learn more about populism.

- Somewhat ironically, as the world globalises, politics becomes more local and regional. This means that cities as well as regions will play a role in sectors previously reserved for states, such as diplomacy, conflict resolution – and crucially climate change. Learn more about urbanisation. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Alliances might form on an ad hoc basis across very different countries to achieve single-issue objectives such as space exploration or climate change. Learn more about how we prevent climate change.

- The interdependent nature of economics might enhance, or reduce, the importance of sanctions as a power tool, because even though states can hurt others by imposing sanctions, they also hurt themselves. Learn more about trade.

Footnotes:

- 10: World Meteorological Organization, ‘July sees extreme weather with high impacts’, 1 July 2018, available at https://public.wmo.int/en/media/news/july-sees-extreme-weather-high-impacts

- 11: International Panel on Climate Change, ‘Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 ºC’, October 2018, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/summary-for-policy-makers/;

- 12: Michael T. Schmeltz et al., ‘Economic Burden of Hospitalizations for Heat-Related Illnesses in the United States, 2001–2010’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, September 2016, Vol.13 No.9

- 13: World Economic Forum, ‘The Global Risks Report 2018’, January 2018, https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2018; For additional reading on climate change please read: Mary Robinson, Climate Justice: Hope, Resilience, and the Fight for a Sustainable Future (Bloomsbury Publishing 2018); Will Steffen et al, 'Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene', (PNAS 2018) https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810141115

- 14: European Commission, ‘10 Trends Reshaping Climate and Energy’, 3 December 2018, available at https://ec.europa.eu/epsc/sites/epsc/files/epsc_-_10_trends_transforming_climate_and_energy.pdf

- 15: Independent, ‘Global warming set to cost the world economy £1.5 trillion by 2030 as it becomes too hot to work’, 19 July 2016, available at https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/global-warming-climate-change-economic-effects-jobs-too-hot-to-work-india-china-a7143406.html

- 16: Peter H. Gleick, ‘Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria’, Weather, Climate and Society, July 2014, available at https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1

- 17: Boyd A. Swinburn et al., ‘The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report’, The Lancet, January 2019, available at https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/global-syndemic

- 18: Demographic projections over the last 40 years have been accurate within a 4% margin. National Research Council, Beyond Six Billion: Forecasting the World’s Population (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2000), p.37

- 19: United Nations, ‘World Population Prospects: Key Findings and Advance Tables, 2017 Revision’, (New York: United Nations, 2017), https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf

- 20: European Environment Agency, ‘Population trends 1950 – 2100: globally and within Europe’, 17 October 2016, available at https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/total-population-outlook-from-unstat-3/assessment-1; Eurostat News release, ‘EU population up to almost 512 million at 1 January 2017’, 10 July 2017, available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/8102195/3-10072017-AP-EN.pdf/a61ce1ca-1efd-41df-86a2-bb495daabdab

- 21: United Nations, ‘World Population Prospects: Key Findings and Advance Tables, 2017 Revision’, (New York: United Nations, 2017), https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf

- 22: United Nations, ‘World Population Prospects: Key Findings and Advance Tables, 2017 Revision’, (New York: United Nations, 2017), https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf

- 23: African Development Bank Group, ‘Briefing Note 4: Africa’s Demographic Trends’, March 2012, available at https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/FINAL%20Briefing%20Note%204%20Africas%20Demographic%20Trends.pdf; The Lancet, ‘Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble’, February 2017, available at https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullTextImages?pii=S0140-6736%2816%2932381-9

- 24: Imperial College London, ‘Average life expectancy set to increase by 2030’, February 2017, available at https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/177745/average-life-expectancy-increase-2030/

- 25: United Nations, ‘World Population Prospects: Key Findings and Advance Tables, 2017 Revision’, (New York: United Nations, 2017), https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2017_KeyFindings.pdf

- 26: Mikhail Denisenko, ‘Will Russia withstand demographic blow.‘ From the series of lectures Forecasting threats’, Argumenty i Fakty (AIF.ru), December 12, 2013, available at http://www.aif.ru/onlineconf/1392868

- 27: Population Reference Bureau, ‘Youth Population & Employment in the Middle East & North Africa’, July 2011, available at http://www.un.org/esa/population/meetings/egm-adolescents/roudi.pdf

- 28: Paul R. Ehrlich, The Population Bomb: Population Control or Race to Oblivion? (New York: Ballantine Books, 1968)

- 29: Bruno Tertrais, ‘The Demographic Challenge: Myths and Realities’, Institut Montaigne, July 2018, p.5 available at their willingness to participate in large-scale and long-term stabilization operations could weaken http://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/publications/demographic-challenge-myths-and-realities

- 30: European Commission, ‘The Ageing Report: Economic and Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU member states (2016 – 2070)‘, 25 May 2018, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/2018-ageing-report-economic-and-budgetary-projections-eu-member-states-2016-2070_en

- 31: European Commission, ibid‘.

- 32: Eurostat, ‘Gender pay gap statistics’, available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Gender_pay_gap_statistics

- 33: Paul Collier, Exodus. How Migration is Changing Our World, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013) p. 61, p. 123

- 34: Yair Ghitza and Andrew Gelman, ‘The Great Society, Reagan’s Revolution and Generations of Presidential Voting’, Columbia University Working Paper, 14 June 2014, available at http://www.stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/research/unpublished/cohort_voting_20140605.pdf; The New York Times, ‘How Birth Year Influences Political Views’, July 2014, available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/07/08/upshot/how-the-year-you-were-born-influences-your-politics.html

- 35: While the United Nations calculate 55% of people to live in cities in 2018, this study assesses that 85% already live in urban areas: United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs, ‘2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects’, available at https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/; http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/cities-report/state_eu_cities2016_en.pdf

- 36: European Commission Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy & United Nations Human Settlements Programme, ‘The State of European Cities’, available at http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/cities-report/state_eu_cities2016_en.pdf

- 37: United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs, ‘2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects’, available at https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/

- 38: Jeremy Gorelick, ‘Raising capital for intermediary cities’, OECD Development Matters, September 2018, available at https://oecd-development-matters.org/2018/09/10/raising-capital-for-intermediary-cities/

- 39: European Commission Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy & United Nations Human Settlements Programme, ‘The State of European Cities’, available at http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/cities-report/state_eu_cities2016_en.pdf

- 40: European Committee of the Regions, ‘Reflecting on Europe: How Europe is perceived by people in regions and cities’, April 2018, p.11, available at https://cor.europa.eu/Documents/Migrated/news/COR-17-070_report_EN-web.pdf

- 41: ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘Global Trends to 2030: The future of urbanization and megacities’, October 2018; Bart Somers, Zusammen Leben: Meine Rezepte gegen Kriminalität und Terror (C.H. Beck: München, 2018)

- 42: Wolfgang Dauth, ‘Assortative matching in cities’, Vox, available at https://voxeu.org/article/assortative-matching-cities

- 43: Alex Ezeh et al. ‘The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums’, The Lancet, February 2017, Volume 389, No. 10068, pp. 547–558

- 44: European Economic and Social Committee, ‘The future evolution of civil society in the European Union by 2030’, 2018, available at https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/publications-other-work/publications/future-evolution-civil-society-european-union-2030

- 45: European Forum for Urban Security, ‘The Nice Declaration: Cities action for preventing violent extremism and securing urban spaces in Europe and the Mediterranean’, October 2017, https://www.nice.fr/uploads/media/default/0001/15/TERRORISME%20EUROPE%20De%CC%81claration%20-%20der%20version.pdf

- 46: Brantley Liddle, ‘Impact of populations, age structure, and urbanization on carbon emissions/energy consumption: evidence from macro-level, cross-country analyses’, Population and Environment, Vol. 35, No. 3 (March 2014): pp. 286-304.

- 47: Alan Berube, ‘City and metropolitan income inequality data reveal ups and downs through 2016’, Brookings, 5 February 2018, available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/city-and-metropolitan-income-inequality-data-reveal-ups-and-downs-through-2016/; Ajaz Ahmad Malik, ‘Urbanization and Crime: A Relational Analysis’, Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, Volume 21, Issue 1, Ver. IV (Jan. 2016) pp.68-74

- 48: Euromonitor International, ‘Income Inequality Ranking of the World’s Major Cities’, 31 October 2017, available at https://blog.euromonitor.com/2017/10/income-inequality-ranking-worlds-major-cities.html

- 49: Ronak B. Patel & Frederick M. Burkle, ‘Rapid urbanization and the growing threat of violence and conflict: a 21st century crisis’, Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, Volume 27, Issue 2, April 2012, pp. 194-197

- 50: The Economist, ‘Where have all the burglars gone?’, July 2013, available at https://www.economist.com/briefing/2013/07/20/where-have-all-the-burglars-gone

- 51: PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC), ‘The World in 2050; The Long View: How Will the Global Economic Order Change by 2050?’, February 2017, available at https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/assets/pwc-the-world-in-2050-full-report-feb-2017.pdf

- 52: International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook – April 2018’, April 2018, available at https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2018/April/text.ashx; European Commission, ‘Economic & Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)’, May 2018, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/ip079_en.pdf

- 53: World Economic Forum, ‘What will global GDP look like in 2030?’, February 2016, available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/02/what-will-global-gdp-look-like-in-2030/; PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC), ‘The World in 2050; The Long View: How Will the Global Economic Order Change by 2050?’, February 2017, available at https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/assets/pwc-the-world-in-2050-full-report-feb-2017.pdf; Wayne M. Morrison, ‘China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States’, Congressional Research Service, February 2018, available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33534.pdf

- 54: Christine Lagarde, ‘Is the world prepared for the next financial crisis’, Foreign Policy, 22 January 2019, available at https://foreignpolicy.com/gt-essay/is-the-world-prepared-for-the-next-financial-crisis-christine-lagarde-economy-recession/

- 55: Homi Kharas, ‘The Unprecedented Expansion of the Global Middle Class’, Brookings, 28 February 2017, available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-unprecedented-expansion-of-the-global-middle-class-2/

- 56: World Bank, ‘Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2016: Taking on Inequality’, Washington: 2016, available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25078/9781464809583.pdf

- 57: Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016)

- 58: The New Yorker, ‘The Psychology of Inequality’, 15 January 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/15/the-psychology-of-inequality; OECD, ‘An Overview of Growing Income Inequalities in OECD Countries: Main Findings’, 2011, available at https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/49499779.pdf

- 59: Jeremy Greenwood, ‘Marry Your Like: Assortative Mating and Income Inequality’, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No.19829, January 2014, available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w19829

- 60: European Parliament, ‘Global Trends to 2035: Economy and Society’, November 2018, p.87, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/627126/EPRS_STU(2018)627126_EN.pdf

- 61: Quoted in World Happiness Report 2017, available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2017/HR17.pdf

- 62: World Happiness Report 2017, available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2017/HR17.pdf

- 63: Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The case for reason, science, humanism, and progress (New York: Viking, 2018), pp.97-120; EuroStat, ‘At risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU-28, 2016’, available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/news/themes-in-the-spotlight/poverty-day-2017

- 64: ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘Global Trends to 2030: New ways out of poverty and exclusion’, January 2019, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-new-ways-out-poverty-and-exclusion

- 65: World Bank, ‘Climate Change Complicates Efforts to End Poverty’, 6 February 2015, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2015/02/06/climate-change-complicates-efforts-end-poverty

- 66: Lars-Erik Cederman, Inequality, Grievances, and Civil War (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2013)

- 67: ESPAS Ideas paper, ‘The Future of Work and Workplaces’, May 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-future-work-and-workplaces

- 68: Eurostat, ‘Europe 2020 Indicators – R&D and Innovation’, June 2018, available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Europe_2020_indicators_-_R%26D_and_innovation; Eurostat, ‘R&D Expenditure’, March 2018, available at http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/R_%26_D_expenditure

- 69: OECD, ‘In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All’, 2015, p.69, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/in-it-together-why-less-inequality-benefits-all_9789264235120-en#page70

- 70: Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, ‘World Oil Outlook 2040’, Vienna 2017, p.13, available at https://www.opec.org/opec_web/flipbook/WOO2017/WOO2017/assets/common/downloads/WOO%202017.pdf

- 71: European Commission, ‘EU Reference Scenario 2016: Energy, transport and GHG emissions Trends to 2050’, July 2016, p.38, available at https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/20160713%20draft_publication_REF2016_v13.pdf. European Commission, ‘2030 Energy Strategy’, available at https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/energy-strategy-and-energy-union/2030-energy-strategy

- 72: International Renewable Energy Agency, ‘The Age of Renewable Energy Diplomacy’, 29 November 2017, available at https://www.irena.org/newsroom/articles/2017/Nov/The-Age-of-Renewable-Energy-Diplomacy

- 73: Bloomberg NEF, ‘Global Storage Market to Double Six Times by 2030’, 20 November 2017, https://about.bnef.com/blog/global-storage-market-double-six-times-2030/

- 74: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, ‘Literacy Rates Continue to Rise from One Generation to the Next’, Fact Sheet No. 45 September 2017

- 75: IHS Markit, ‘Number of Connected IoT Devices Will Surge to 125 Billion by 2030, IHS Markit Says’, 24 October 2017, available at https://technology.ihs.com/596542/number-of-connected-iot-devices-will-surge-to-125-billion-by-2030-ihs-markit-says

- 76: IATA, ‘2036 Forecast Reveals Air Passengers Will Nearly Double to 7.8 Billion’, 24 October 2017, available at https://www.iata.org/pressroom/pr/Pages/2017-10-24-01.aspx

- 77: OECD, ‘Strategic Transport Infrastructure Needs to 2030’, available at https://www.oecd.org/futures/infrastructureto2030/49094448.pdf

- 78: PWC, ‘By 2030, the transport sector will require 138 million fewer cars in Europe and the US’, January 2018, available at https://press.pwc.com/News-releases/by-2030--the-transport-sector-will-require-138-million-fewer-cars-in-europe-and-the-us/s/a624f0b2-453d-45a0-9615-f4995aaaa6cb

- 79: Nita Madhav et al, ‘Pandemics: Risks, Impacts, and Mitigation’, in Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty, (Washington DC: World Bank, 2017) 3rd edition.

- 80: Cognizant, ‘The Future of Air Travel: Eight Disruptive Waves of Change’, June 2017, available at https://www.cognizant.com/whitepapers/the-future-of-air-travel-eight-disruptive-waves-of-change-codex2566.pdf

- 81: Parag Khanna, ‘Urbanisation, technology, and the growth of smart cities’, Singapore Management University, November 2015, available at https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=ami

- 82: ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘Global Trends to 2030: Identities and Biases in the Digital Age’, October 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/sites/default/files/generated/document/en/Ideas%20Paper%20Digital%20Identities%20ESPAS-EPSC_V08.pdf

- 83: Jonathan D. Moyer, Tim Sweijs, Mathew J. Burrows, Hugo van Manen, ‘Power and influence in a globalized world’, The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, February 2018, available at https://hcss.nl/report/power-and-influence-globalized-world; Yaging Qin, A Relational Theory of World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018)

- 84: Karl Deutsch and J. David Singer, ‘Multipolar Power Systems and International Stability’, World Politics, N.16, 1964, p.390. Hans Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, (Alfred A. Knopf; New York, 1973), p.341-342.

- 85: Karl-Heinz Kamp, ‘NATO’s Short-Term vs. Long-Term Challenge’, NATO Defence College Policy Brief, March 2019

- 86: NATO, ‘Framework for Future Alliance Operations’, 2018, available at https://www.act.nato.int/images/stories/media/doclibrary/180514_ffao18-txt.pdf; Barbara Lippert et al., ‘Strategische Autonomie Europas : Akteure, Handlungsfelder, Zielkonflikte’, SWP-Studie 2, February 2019, available at https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2019S02/

- 87: François Godement & Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, ‘La Chine à l’ONU : de l’influence au leadership par défaut ?’, unpublished paper

- 88: Robert Keohane & Joseph Nye, Power and interdependence: world politics in transition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1977)

- 89: More in Common, ‘Attitudes Towards Refugees, Immigrants, and Identity in France’, July 2017, available at https://moreincommon.squarespace.com/france-report; More in Common, ‘Attitudes Towards National Identity, Immigration, and Refugees in Germany’, July 2017, available at https://moreincommon.squarespace.com/germany-report;