ON THE ROAD TO THE FUTURE:

THE CATALYSTS

In some ways, thinking about the future is farsighted: we are good at seeing things further away, but the closer things are, the blurrier they get. A trend that is shorter in lifespan is therefore more difficult to identify than one that will unfold over several decades – simply because it is more dynamic and rapid. We call these trends ‘catalysts’ because as in chemistry, they accelerate (or decelerate) both mega-trends and other catalysts. In contrast to mega-trends, humans can change them more easily – but they produce change themselves, too. Catalysts unfold anywhere between six months and five years, which is why they are felt acutely by people in their daily lives. In this report, they are therefore set in a timeframe up to 2025.

One example of a catalyst is violent conflict: a development for which the solution is likely to call for a quick reaction, and trigger other, fastdeveloping trends such as migration or populism, but caused itself by mega-trends such as demographics or urbanisation.

Because catalysts appear faster than mega-trends, they push humans to take action quicker than on slow-moving mega-trends. Therefore,

A significant part of a decisionmaker’s time will be spent on catalysts rather than mega-trends.

The trends outlined below all fall into this category: we have a high degree of probability when it comes to them, but we also have to manage a certain degree of uncertainty linked to human unpredictability.

TRADE WILL INCREASE

Until recently, the development of global trade would have been found in the mega-trend section rather than with the catalysts. But rising protectionism, not only in the United States, and the uncertain impact of Brexit on both British and European markets, seem to jeopardise the progressive integration of the global trade system to the extent that its future seems less certain now.

That said, international trade is still going strong: regional and preferential trade arrangements have been on the rise for the last two decades and continue to do so. The EU is negotiating or finalising agreements with several states (having recently concluded one with Japan) and similar agreements are under way elsewhere, among African states, for instance. In the absence of a wide-ranging reform of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and global trade governance, open plurilateral agreements may become a popular option in the future.90

There is a simple reason for this: open trading systems are beneficial for economies of a similar structure. This, and the fact that the United States alone cannot undo two decades of a trend, is a good reason to assume that despite its questioning by a major player, the system will continue to expand.91 In 2016, total trade between WTO members (covering 98% of world trade) was $16 trillion in merchandise and $4.7 trillion in services – a testimony to globalisation.92

Even the United States will find that its current approach, aimed at protecting workers and domestic production from globalisation, may no longer be very effective. For instance, value and production chains are more global than ever, and tariffs would do little to encourage domestic manufacturing, and hence, preserve jobs. True, this is slightly different when it comes to final products; here, tariffs may still lead to certain rearrangements. But in any circumstance, imposing tariffs would mean increasing the cost of goods, which ultimately means consumers pay a higher price. Hence, American protectionism will not have the desired results. In addition to these current tensions, global trade volume will be impacted by China’s gradual switch towards domestic activities, which reduces trading volumes in absolute terms. It is expected that this trend will continue in the long run, coupled with the expansion of trade in the Global South. Trade volumes between emerging economies are expected to increase faster than those between the developed ones.93 This will add more weight to calls for a rebalancing of global trade governance.

Trade in services and data flows will be crucial in the years to come. Furthermore, over the medium to long term, intensification of trade either in terms of goods or services will benefit the world economy by spurring global efficiency, knowledge transfers, and innovation. For all of these reasons,

We are cautiously optimistic that in the mid- to long-term, trade will continue to grow, especially trade in services.

As the European market for goods is already fully developed and highly integrated, what will hamper European trade volume growth is the handicap stemming from a fragmented market in services. Data flows and access to service markets are predicted to grow substantially in the coming years, but the slow and inefficient integration of the European digital market and market for services in general may constrain this.94

What does this mean?

There is a certain degree of uncertainty when it comes to the future of trade, but there is also a high degree of probability: even though some governments currently favour protectionism, there are signs that the global trade system is not about to collapse. In fact, populist moves towards isolationism are not about trade, but about unemployment and poverty rates as its perceived consequences.

Protecting the international trade order therefore requires policy measures at the national level first, including a renewed focus on redistributive policies. And there are other aspects to consider:

- Many associate poverty and unemployment with globalisation, but changes in tax and transfer systems have played a greater role in the decline of income redistribution than trade openness.95 Learn more about populism.

- How global trade and its governing institutions will evolve will depend in large part on China. Learn more about geopolitics.

- Digitalisation will lead to an increase in new sectors which will affect not just economies generally but also trade as services – and jobs - could move abroad. Learn more about new technologies.

- Modern technology could also mean that production can move closer to the consumer, reducing the carbon footprint of goods transport. Learn more about how we prevent climate change.

- Global connectivity in terms of trade might enhance, or reduce, the impact of sanctions. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Trade is not just about exporting goods: it is also about exporting standards, be it in the domain of labour, environment, or data protection. Trade agreements increasingly include such provisions – with potentially positive effects on climate change, demographics, and global poverty rates.96 Learn more about how we prevent climate change. Learn more about demographics. Learn more about economics.

FOOD AND WATER WILL HAVE TO BE WATCHED

The earth is a finite place when it comes to resources – or so it seems. Warnings of food and water insecurity have become a regular feature of international politics – and indeed, even in the EU, water scarcity and droughts affect one-third of its territory. (It is worth noting that 44% of European freshwater is used to cool thermal power, and only 24% for irrigation.)97 Both food and water insecurity are therefore seen as mega-trends but are in fact – in their nature and impact – catalysts as they emerge over a short period of time and human action can have an immediate impact.

To understand this, we need to look at what food and water insecurity actually are. There are three dimensions to this: first, sheer availability – are food and water obtainable or not? Second, affordability: at what price are they available? And third, are they of sufficient quality?

When we apply these dimensions, we can see that we have different degrees of insecurity. For instance, the first dimension, availability, is in fact a dying category: famines have decreased to historically low levels all over the world. This is because our understanding of famines has evolved: while for many years experts believed that famines were caused by a shortfall in food availability, the insight emerged in the 1980s that famines actually occurred when food was available – but not accessible. This means that human complicity plays a crucial role in the onset of famines, and that

Production and transport costs and governance are more important to our thinking about food insecurity than the idea of a planet running out of resources.

The current understanding of food security is also influenced by food quality – food that not only feeds, but provides nutrients and helps individuals live the longest and healthiest life possible. When we speak about food insecurity in Europe, for instance, we mainly mean food that leads to health issues such as obesity rather than a lack of access to food. Elsewhere, however, both water and food insecurity are real issues that need to be addressed in the coming years to assist the 700 million people who currently do not have basic access to water, and the 815 million people living in food insecurity – but neither issue is due to a lack of resources, rather to (mis)management and quality standards.98

Indeed, the ideas of ‘water wars’ and ‘food wars’ have captured the imagination of many, but a direct link between a lack of affordable water and food on the one hand, and violence on the other has not been established yet. Obviously, food prices correlate with a number of indicators associated to conflict (such as low GDP, levels of development, etc.), but there is no evidence proving that hunger or thirst themselves directly caused a war. Similarly, water insecurity is mostly the result of poor infrastructure and water management, rather than the planet drying up. Instead, both water and food are more accurately described as conflict accelerators rather than conflict triggers.99

What does this mean?

Access to food and water is highly dependent on other aspects unrelated to their actual availability – which means they can intensify existing conflicts rather than create new ones. That said, both food prices and signs of water stress serve as important indicators that there is a larger policy problem – which could indeed lead to conflict and mass displacement. In the coming years, we will therefore witness moments of water and food stress outside Europe – and we should interpret them as signs that things are amiss more generally in a certain state or region.

- Climate change will exacerbate both water and food insecurity in areas that are already prone to conflict, such as Africa and the Middle East. The IPCC says that climate change will expose 1 billion people to water scarcity in the coming years.100 Learn more about how we prevent climate change. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Food and water indicators correlate with conflict; they can therefore be used as early warning signs. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Europe suffers from over- rather than undernutrition, with detrimental health effects. Learn more about how we improve ageing.

WARFARE WILL CHANGE

It is fair to say that the entire discipline of foresight was born out of the desire to know where, when, and how future wars would unfold.101 But despite this burning interest, it is not the area where predictions have been most accurate – in large part, because we tend to overestimate the impact of technological progress, overlook the complexity of conflict drivers, and underestimate the lethality of comparatively unsophisticated weapons’ systems.102 That said, reflecting on the future of war is still crucial because violent conflict will continue to be a feature of the coming years despite our best efforts to avoid it.

There are a few things we can say with certainty about future conflicts: for instance, extrapolating from past trends, we can assert that while interstate wars have become less prevalent, we will still witness one per decade at the global level.103 This can take place in many different forms: at sea, in the air, on land, in space – and in the cyber domain. But it can also take on hybrid forms and come without a formal declaration or open acts of war: propaganda and political agitation, too, will be part of the offensive portfolio of others. In addition, the current unravelling of the nonproliferation regime re-opens the possibility of stand-offs between nuclear powers.104

The number of intrastate (or civil) wars will either remain the same, or increase in the coming years – that is, to over 40 ongoing conflicts per year. We can assume this because all the indicators for the drivers of conflict are projected to grow: climate change, inequality, youth bulges, repression, the unchecked spread of small arms and the connectivity of non-state actors all mean that states that are already facing numerous internal challenges will probably face even more difficulties in the coming years. We can therefore assume that

The majority of conflicts that break out in the coming years will take place within a state, rather than between states.

Unfortunately, a fair number of these conflicts will be situated in areas of strategic concern to Europe, especially in the Middle East and North Africa.105 Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Libya continue to be at high conflict risk, regardless of the current status of combat operations.

But it is not just the Arab world which is at risk, so are several areas in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as the Lake Chad Basin, the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and Central Africa. Although as a Union we are committed to the ideal of conflict prevention, neither we nor others have been able to decode the precise origins of war – despite the fact that conflict prevention could save anywhere between $5 and $70 billion a year.106

Different types of warfare will require very different skillsets from our armed forces: whereas conflict stabilisation is normally less sophisticated and more manpower intensive, it also lasts longer and requires long-term political commitment. Conflicts that we are the victim of can happen at any time, in any place, in any way: a 360° type of conflict for which we are currently not ready – but others are. It might include modern technology in the shape of unmanned aircraft and ‘killer robots’ – but there are other more pressing threats. The real danger emanates from all those types of attack which we do not immediately recognise as such, be it infiltration, media and political manipulation or cyber-attacks.

What does this mean?

Although Europe has mostly lived in peace since its inception as a Union, this does not mean that it will remain unconcerned by future conflicts. On the contrary, to navigate the coming decade peacefully, Europe needs to ready itself for all the aspects of war likely to unfold – while also engaging in conflict prevention and resolution.

- At the moment, our defence sector is not ready to face complex conflicts – among other things because we are fragmented. Learn more about how we manage conflict.

- Connectivity means that cyberspace will be a key front in any conflict, but areas that are less linked to the online realms will be affected less by this trend. Learn more about connectivity.

- Every conflict fought with violent means over the last 200 years produced surprising new technological developments or doctrines. Technological progress could make wars quicker, more (or less) lethal, and more multidimensional. Learn more about new technologies. Learn more about how we deal with new technology.107

- Europe can no longer fully rely on the United States’ security umbrella as Washington’s strategic attention is already shifting to Asia. Improving not only its defence capabilities, but also rethinking how it manages conflict will be key to protecting itself in the future.108 Learn more about geopolitics. Learn more about how we manage conflict.

- The unravelling of agreements designed to prevent an arms race means that the likelihood of conflict will increase. Learn more about geopolitics.

- Big data can make conflict prediction more accurate than it is today – but not to a dramatic extent.109 Learn more about new technologies.

- Instability in the Arab world will have an impact on European migration levels and politics. Learn more about migration. Learn more about demographics. Learn more about populism.

- A large youth population plays a role in conflict onset. Learn more about demographics.

- Conflict onset correlates, amongst other things, with political, social and economic inequality.110 Learn more about economics.

- International law still addresses mainly interstate rather than intrastate conflict, making internal conflict the battleground where most pain is inflicted in humanitarian, economic and political terms. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Peacekeeping is an expensive and manpowerintensive tool to settle civil wars – both aspects are at odds with Europe’s current strategic posture. Learn more about demographics. Learn more about economics.

- Because the world will be more connected, human suffering will be visible to a much larger audience – this can be, of course, manipulated to increase pressure on decision-makers to end civil wars elsewhere. Learn more about connectivity. Learn more about populism. Learn more about how we deal with conflict.

- Abroad, intrastate wars will unfold increasingly within cities, leading to a new type of urban warfare. Learn more about urbanisation.

TERRORISM WILL REMAIN

Like violent conflict, terrorism is difficult to predict – indeed, the element of surprise is in its very nature. However, we can expect with a sad degree of certainty that terrorism will not disappear as a phenomenon in Europe (or indeed elsewhere) in the coming years. This is connected to several dynamics.

First, the pool for Islamic State (IS) recruits is not shrinking: there is potential for returnees from Syria and Iraq, but also for released convicts to conduct terrorist attacks. More than 1,500 terrorists will be released around 2022 in the European Union as they received sentences of five years on average.111 In addition, home-grown radicalisation continues to be the driver for terrorist attacks in the Union – at the moment, between 50,000 and 100,000 individuals are being monitored for radical potential, a pool that could expand.112

And despite its current setbacks in the Middle East, IS continues to express the intent to conduct terrorist operations in Europe; the strategic vacuums in Somalia, Libya and Egypt’s Sinai continue to provide a safe haven for its fighters to prepare such attacks and conduct strategic outreach to recruits.113 The threat is also growing in the Balkans, where Salafi-jihadism was more successful in recruiting than often assumed: more than 1,000 citizens from these countries joined IS in Syria and Iraq between 2014 and 2016.114 In addition, al-Qaeda’s strategic approach (weakening the ‘far enemy’, i.e. Western states, first before establishing a state) has been validated by IS’ defeat, meaning that its resurgence is a likely possibility. In addition, a new jihadist entity can emerge with similar objectives, building on the IS experience in Syria and Iraq.

It is worth noting that while jihadist terrorist attacks dominate the news, they constitute only 16% of terrorist attacks; 67% of attacks were of a separatist nature, 12% left-wing and 6% rightwing. This last category has been increasing significantly.

What does this mean?

Terrorism will continue to be a feature of Europe’s security landscape in the coming years, well beyond the threat of IS: anarchic, right- or leftwing terrorism continues to pose a serious problem to the EU but receives much less attention. While most European terrorist networks operate across national borders, governmental cooperation on the issue is still not as developed as it could be.

- All terrorist networks use the internet to recruit, exchange information, funds and knowledge. Learn more about connectivity.

- Terrorism is often linked to conflicts occurring outside Europe. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- Right-wing terrorism is linked to populism. Learn more about populism.

- Jihadist terrorism is used by populist parties to generate a xenophobic environment and win votes. Learn more about populism. Learn more about migration.

- Home-grown terrorism is linked to poor integration and inequality. Learn more about economics.

TECHNOLOGY WILL SPRINT AHEAD

Technological innovation is a meta-trend in the sense that it permeates virtually all other aspects of human life. It appears here in the catalyst section because it develops much faster than mega-trends. And while technological progress has been an ongoing development, there is a new element to it as now

Machine intelligence is beginning to rival human intelligence.

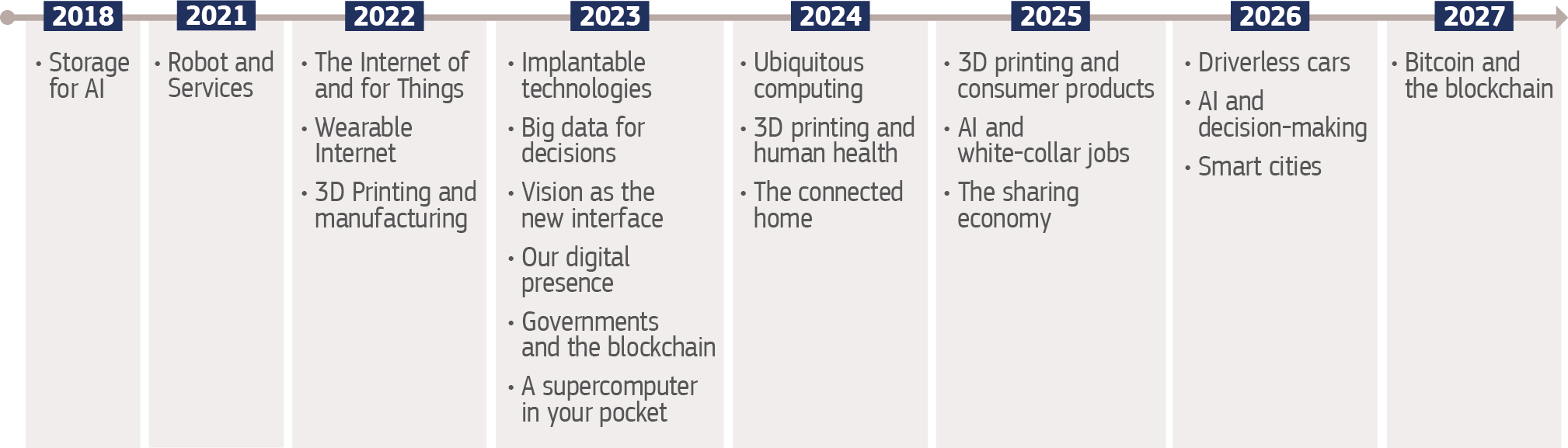

This will happen in the coming years already because innovation is expected particularly with regard to the Internet of Things (IoT), AI, advanced robotics, wearables and 3D printing. Other developments such as blockchain, new energy storage methods and 5G will also have an impact.115 In total, the market for key digital technologies will reach €2.2 trillion by 2025.116 In fact, an important share of Europe’s future growth potential resides in this area.

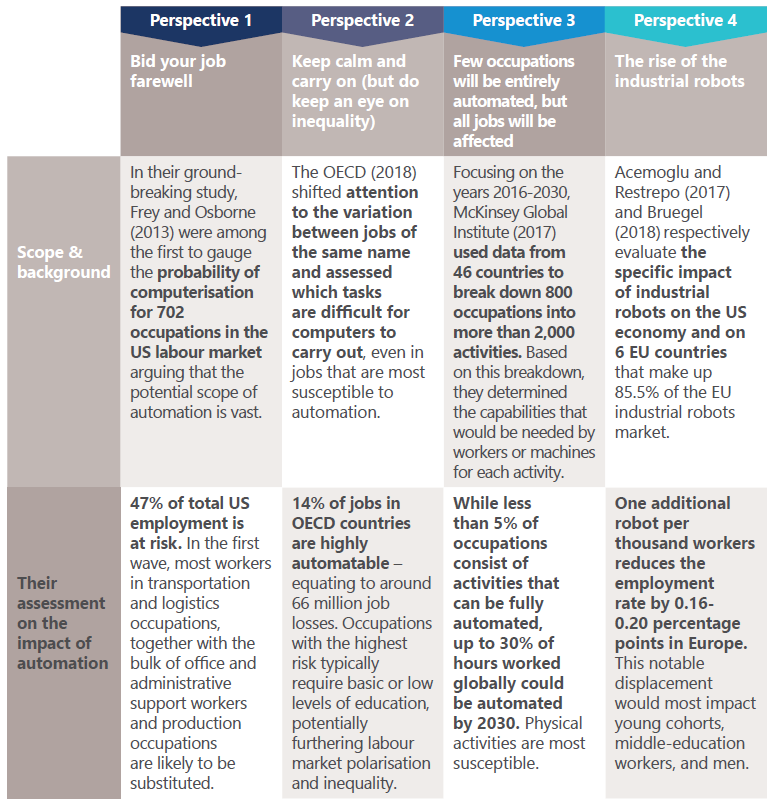

In many ways, these innovations will make human life easier, not only in our day-to-day lives, but because they represent economic and employment potential. In other ways, they are a source of concern: for instance, we know that they will disrupt the labour market by destroying certain jobs – but also by creating new ones.117 Machines are likely to replace humans in areas that are repetitive and mechanical, rather than take over entire labour markets. One study showed that those professions to be hit the hardest will include drivers, mail sorters and telephone operators.118 In return, new jobs will emerge: according to some studies, the vast majority of jobs of the future do not exist yet.119 However, this change is unlikely to be sudden or brutal, but incremental.120

And technology will not just affect day-to-day business: it will also be a determining factor in how Europe positions itself in the world as both a powerful technological innovator and a setter of ethical standards when it comes to prevent the use of machines for warfare, totalitarian control, and disinformation. At the moment, Europe is at risk of being left behind by China and the United States, leaving others to define a crucial area of the future.121

That said, Europe is well-equipped to take on the new technological challenge: it has high levels of education, connectivity and disposable income available.

What does this mean?

In the coming years, the way we work, fight, age, communicate, solve problems, travel, trade, exchange information, live in cities, solve crimes, do business, vote, and connect to our loved ones will all be changed. This are not developments Europe can stop, but it can shape them. Indeed, if we choose not to, others will do it for us.

Although robotics will replace jobs, this does not mean we are heading towards a world where robots dominate humans. Learn more about how we deal with new technology.

- Modern technology also makes us more vulnerable in the cyber domain with regard to both crime and cyberattacks.122 Learn more about how we manage conflict.

- Leadership in technological innovation is now, even more than in the past, a key ingredient in global power projection – if Europe wants to be part of this, it will have to invest more in R&D, education and skill development.123 Learn more about geopolitics.

- Although the concept of life-long learning has been discussed for some time, it is becoming increasingly important now, as humans need to rely on those skills machines do not have – this has implications for education systems, as well as for older workforces already employed.124 Learn more about how we improve ageing.

- Some technologies will allow for tighter controls within totalitarian societies, undermining Europe’s democratic ideal. Learn more about how we protect democracy.

- New technologies will change how human conflict unfolds – whether for better or worse is our decision. Learn more about conflicts to come.

- New technologies can help meet some of the challenges of European longevity. AI can improve social connectivity and emotional health, and cognitive and physical ability.125 Learn more about how we improve ageing.

- New technologies might be able to help mitigate the effects of climate change. CO2 capture technology can directly facilitate 30% of the emissions cuts needed by 2030, and indirectly affect the rest through influencing consumer habits, scaling up a sharing economy and supporting business transformation to a circular economy.126 Learn more about how we can prevent climate change.

- Low-skilled migration has slowed new technology development down in sectors such as food and agriculture as there is not yet enough incentive to develop alternatives. Learn more about migration.

- Should industry disruptions occur and largescale unemployment set in, populist parties could thrive. Learn more about populism.

PEOPLE WILL MOVE

Superficially, migration looks very much like a mega-trend over which we have little influence. But in fact, migration is just a symptom of megatrends – of demography, economy, connectivity, and environmental change. But precisely because it sits at the intersection of other trends, it is difficult to predict.128 Statistically,

Only 60% of predictions concerning migration were accurate.

Regarding Europe, what we do know is that numbers of irregular border arrivals tend to be cyclical, rising and falling roughly on a fiveyear basis, and with a big influx every 20 or so years, which reflects a significant shift in the international order. And, of course, there is a marked difference between a refugee crisis resulting from an acute conflict, and migrants moving for economic reasons.

In addition, we know that most irregular migrants in Europe – traditionally at least – have been visa ‘overstayers’ who entered by regular means, rather than the – traditionally – small numbers who arrive by irregular means. According to current projections, 1.8 billion individual travellers will cross international borders each year by 2030 – but how many of those will overstay is impossible to say.129 When it comes to foresight, the lesson from the 2015-2016 migration crisis is clear: action matters. The EU regained control only when it started trying to define the future on its own terms rather than second-guess where the next flow of people would come from. As soon as the EU-28 started using their combined weight and exercising influence abroad, pushing Morocco or Turkey for reforms, job creation or border controls, the migration flows became more predictable.

That means the EU has some scope to influence migration. It could usefully view migration as a way to identify underlying mega-trends, and then find smarter ways to channel human reactions to them – to joblessness or to drought or to war. By contrast, if the EU views the threat of mass migration as some kind of inevitability, this fear could very well be self-fulfilling – bad European policies could help turn migration into an uncontrolled driver of demographic shifts, say, or a factor that turns environmental change into a source of civil unrest.130

What does this mean?

Considering the cyclical nature of migration, another wave is to be expected in the coming years – but it is not clear what its extent will be, and whether Europe will be its target or not. That said, migration will continue to feature on decision-makers’ agendas. One of the major points for action in the medium term is to create a reasonably robust global framework on migration. For Europe, the scope to take a lead role in this has grown as the US has dropped out of the Global Compact for Migration (GCM) process. The 2018 UN GCM could, despite its shortcomings, serve as a basis for this framework because it takes place at a time when the organisation is not preoccupied with traditional points of contention between the Global North and South.

- The main driver for migration is the global economy: the rise in income has meant that people in developing economies gain enough income and international sensibility to cross borders. It is now established that emigration rates tail off only when a country breaches the upper-middle income threshold.131 Learn more about economics.

- Poverty, the classic push factor, tends to lead to local migrations, such as from countryside to town or to nearby countries. Learn more about economics.

- Connectivity strongly influences migration flows, because measures by authorities and information by diaspora networks are communicated to and within migrant communities. Learn more about connectivity.

- Climate change will influence migration into cities, rather than to Europe. Learn more about urbanisation. Learn more about how we prevent climate change.

- Migration is increasingly used as a diplomatic bargaining chip. China uses large-scale exchange programmes to secure resource concessions in Central Asia and Africa, for instance, while Russia leverages the dependence of nearby states on labour remittances to extend its influence. The EU itself uses visa liberalisation and ‘mobility partnerships’ to build relationships with developing economies. Learn more about multilateralism.

- Although theories exist that an increase in population elsewhere will lead to increased numbers moving to Europe, because we are fewer, migration is not a spatial zero-sum game – and studies disprove this fear.132 Africa, for instance, remains one of the least populated areas on earth, and migration there remains largely within the continent. Learn more about demographics.

- Migration is only a limited panacea to Europe’s declining population rates.133 Learn more about how we improve ageing.

- Migrants are at much higher risk of poverty and inequality in Europe than non-migrants. Learn more about the economy.

- Populists use migration influx to leverage xenophobic attitudes to their advantage. Learn more about populism.

POPULISTS WILL TRY

A populist appeal to the will of ‘the people’ and a rejection of (liberal) elites has been a steadily growing phenomenon in Europe over the last two decades, giving cause for concerns and fears over the stability of our societies. However, whilst populism seems to appear out of the democratic blue, it has surfaced repeatedly in Western systems since the late 18th century. And while some anti-system movements used populist methods to topple democracies in Germany or Italy, most populist waves did not seek, or succeed, in changing a political system. Instead, the vast majority of waves in the 19th and 20th century in the United States and Europe dissipated once their concerns were addressed through economic and political reforms.

So what is populism exactly and what does it seek? We use here the definition of populism as ‘parties and politicians that claim to represent the true will of a unified people against domestic elites’.134 In this sense, populism is not an ideology (it can be found to the left and right of the political centre), but rather an exclusionary approach to politics, dividing the landscape into friends or enemies. In that sense, it is more political entrepreneurship than ideology.

Populist concerns revolve, to diverging extents, around three conflated issues: economic crisis, threatened identity, and an unresponsive political system.135 However, the weight of these individual elements can vary significantly: the recent American populist wave, for instance, did not occur in a period of acute economic crisis, but it still displayed the other ingredients for a populist surge. Growth had slowed down, inequality had risen, the financial crisis had eroded trust in decision-makers, and the rise of China and automation fuelled fears of an imminent wave of unemployment; insecurity also existed in identity terms – at the international level, the perception that the United States was losing influence, and at the national level, that traditional identity was under threat by increasing levels of cultural and gender diversity. The fact that decision-makers (‘elites’) seemed to accept or even embrace all of the above only fuelled resentment further.

The American case shows that populism is less about past performance and more about future expectation.

But although populists are very much futureoriented when it comes to their concerns, economically speaking, they will take a short-term and redistributive approach to policy issues – in budgetary terms, they prefer spending (e.g. the establishment of a minimum wage or increased pensions); in environmental terms, they might curb restrictions on business to protect jobs; in social terms, they will identify ‘others’ as the cause of the problem, be it in gender, cultural or financial terms.

But at the heart of populism are genuinely felt concerns: it was populist waves which led to the creation of social insurance policies in Germany in 1880, to the ‘New Deal’ in the United States in 1933, and the provision of paid leave in France and Belgium in 1936. The key is to identify and address such measures designed to tackle root causes – but they will take time to take effect.

What does this mean?

While it is clear that populism is triggered by crises (and indeed, triggers crises itself), it is less clear why it appears in some settings and not in others. It is for this reason that it is difficult to foresee the future of European populism in the coming years. That said, we understand what populist parties thrive on:

- Populism is not just about domestic concerns: when citizens feel that their state has lost global importance, they are more susceptible to populist messaging.136 Learn more about how we position Europe in the world.

- Populism is not just a movement, it is also a political style, relying on emotional, and even overtly offensive language to stress the urgency of its demands, and their proximity to the people. Institutions like the EU do not easily master this style. Learn more about how we protect our democracies.

- Populists seek to protect their electorate from international competition, which is why they favour tariffs. Learn more about trade.

- Populism thrives on perceived social immobility; one of the ways to stimulate growth is to improve education, especially life-long learning for older generations. Learn more about demographics. Learn more about economics.137

- Measures to counter a populist narrative on inequality can include the strengthening of an inheritance tax to mitigate the accumulation of wealth, tax incentives for workers to invest in stocks, increasing measures against tax avoidance and evasion, and putting caps on top salaries – but ultimately, populism is more than an economic phenomenon, and instead expresses a larger sense of malaise.138 Learn more about how we protect democracy.

- Populists prefer direct democracy over representative democracy, and proportional systems to non-proportional ones. Learn more about how we protect democracy.

- Populists generally prefer to use new forms of communication to bypass established media; social networks are favoured tools because fake news, rumours and conspiracy theories are not easily dispelled and because social media promotes ‘echo chambers’ where users are exposed only to news items and topics they already care about.139 Learn more about connectivity.

- Populism takes advantage of the complexity of an international environment which is hard to understand. Higher levels of education, a side effect of Europe’s longer-living population, might be a useful antidote as people feel more comfortable with complexity. Learn more about how we improve ageing.

- Populism is not defeated by adopting its style, but by addressing the underlying fears of insecurity – and challenging negative narratives with positive ones. Learn more about economics.

Footnotes:

- 90: Bertelsmann Foundation, ‘Interim Report: Bolstering Global Trade Governance’, 2017, available at https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/interim-report-bolstering-global-trade-governance/

- 91: World Economic Forum, ‘Brexit, the US, China and the future of global trade’, 12 February 2018, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/02/brexit-china-global-trade/

- 92: World Trade Organization, ‘World Trade Statistical Review 2017’, available at https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/wts2017_e/wts17_toc_e.htm

- 93: World Trade Organization, ‘Strong Trade Growth in 2018 Rests on Policy Choices – Press Release’, 12 April 2018, available at https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres18_e/pr820_e.htm

- 94: ESPAS Ideas Paper, ‘The Future of International Trade and Investment’, 20 September 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/future-international-trade-and-investment-espas-ideas-paper

- 95: Orsetta Causa, Anna Vindics and Oguzhan Akgun, An empirical investigation on the drivers of income redistribution across OECD countries, OECD 2018 http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=ECO/WKP(2018)36&docLanguage=En

- 96: European Commission, ‘Reflection paper on harnessing globalisation’, 10 May 2017, available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/publications/reflection-paper-harnessing-globalisation_en

- 97: European Commission, ‘EU Science Hub: Water’, available at https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/research-topic/water

- 98: World Economic Forum, ‘Why we need to address global water security now’, December 2015, available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/12/why-we-need-to-address-global-water-security-now/;

- 99: Slate, ‘The “Water Wars” Trap: Climate change may threaten security, but countries won’t be going to war over water any time soon’, 9 December 2015, available at https://slate.com/technology/2015/12/water-wars-caused-by-climate-change-arent-something-we-need-to-worry-about.html

- 100: International Panel on Climate Change, ‘Working Group II Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability’, https://www.ipcc.ch/working-group/wg2/?idp=180

- 101: Lawrence Freedman, The Future of War: a history (Hurst: London, 2017)

- 102: Florence Gaub, ‘The benefit of hindsight: What we got wrong – and why’, Brief 1, 2019, European Union Institute for Security Studies, available at https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/benefit-hindsight

- 103: Thomas S. Szayna et al., ‘What are the trends in armed conflicts, and what do they mean for US defence policy?’, RAND Corporation, available at https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1900/RR1904/RAND_RR1904.pdf; Human Security Report Project, Human Security Report 2009/2010: the causes for peace and the shrinking costs of war (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011)

- 104: European Defence Agency, ‘Exploring Europe’s capability requirements for 2035 and beyond’, June 2018, available at www.eda.europa.eu%2Fdocs%2Fdefault-source%2Fbrochures%2Fcdp-brochure---exploring-europe-s-capability-requirements-for-2035-and-beyond.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3Y8wHQpEnF2jjn5CZvpVD0; World Economic Forum, ‘10 trends for the future of warfare’, November 2016, available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/the-4th-industrial-revolution-and-international-security/

- 105: Institute for Economics and Peace, ‘Global Peace Index 2018’, available at http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2018/06/Global-Peace-Index-2018-2.pdf

- 106: World Bank, ‘The Economic Cost of Conflict’, April 2018, available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2018/03/01/the-economic-cost-of-conflict

- 107: ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘The Future of Warfare’, September 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/sites/default/files/generated/document/en/ESPAS%20Ideas%20Paper%20The%20Future%20of%20Warfare%20FINAL.pdf; Foreign Policy, ‘The Future of War’, Fall 2018

- 108: Antonio Missiroli (ed.), Enabling the future: European military capabilities 2013 – 2035: challenges and avenues, Report No.16 (European Union Institute for Security Studies: Paris, 2013), https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/enabling-future-%E2%80%93-european-military-capabilities-2013-2025-challenges-and-avenues

- 109: Chris Perry, ‘Machine Learning and Conflict Prediction: A Use Case’, International Journal of Security and Development, 2013, Vol.2 No.3; Havard Hegre et al., ‘Predicting Armed Conflict, 2010 – 2050’, International Studies Quarterly, June 2013, Volume 57, Issue 2; Lars-Erik Cederman & Nils B. Weidmann, Predicting armed conflict: Time to adjust our expectations?’, Science, 03 Feb 2017, Vol. 355, Issue 6324, pp. 474-476; Thomas Chadefaux, ‘Conflict forecasting and its limits’, Data Science, No.,1, 2017

- 110: Gudrun Østby, ‘Horizontal Inequalities and Political Violence’, University of Oslo, 2010, available at https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/13093/dravh-Ostby.pdf?sequence=3

- 111: Marc Hecker, ‘137 nuances de terrorisme. Les djihadistes de France face à la justice’, Focus stratégique, n°79, April 2018, p.52, available at https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/hecker_137_nuances_de_terrorisme_2018.pdf; Europol, ‘European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2018’, available at https://www.europol.europa.eu/activities-services/main-reports/european-union-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2018-tesat-2018

- 112: Europol, ‘European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2018’, available at https://www.europol.europa.eu/activities-services/main-reports/european-union-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2018-tesat-2018

- 113: European Parliament, ‘The return of foreign fighters to EU soil: Ex-post evaluation’, May 2018, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/621811/EPRS_STU(2018)621811_EN.pdf

- 114: Peter Neumann, ‘Defeating extremism in the Balkans’, EURactiv, 3 May 2018, available at https://www.euractiv.com/section/enlargement/opinion/defeating-extremism-in-the-balkans

- 115: Eurasia Group, ‘Eurasia Group White Paper: The Geopolitics of 5G’, November 2018, available at https://www.eurasiagroup.net/live-post/the-geopolitics-of-5g

- 116: The Guardian, ‘Digital economy to hit $23 trillion by 2025’, 25 April 2018, available at https://guardian.ng/technology/digital-economy-to-hit-23-trillion-by-2025/

- 117: ESPAS Ideas paper, ‘The Future of Work and Workplaces’, May 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-future-work-and-workplaces; World Intellectual Property Organisation, ‘WIPO Technology Trends 2019: Artificial Intelligence’,

- 118: World Economic Forum, ‘These are the jobs that are disappearing fastest in the US’, 12 May 2017, available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/05/these-are-the-jobs-that-are-disappearing-fastest-in-the-us; Max Tegmark, Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017) p.122

- 119: Huffington Post, ‘85% Of Jobs That Will Exist In 2030 Haven’t Been Invented Yet: Dell’, 14 July 2017, available at https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2017/07/14/85-of-jobs-that-will-exist-in-2030-haven-t-been-invented-yet-d_a_23030098/?guccounter=1&guce_referrer_us=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_cs=W641Dlw1CwBKX9EmsjvlAw

- 120: World Economic Forum, ‘Deep Shift: Technology Tipping Points and Societal Impact’, September 2015, available at http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GAC15_Technological_Tipping_Points_report_2015.pdf

- 121: Kristin Shi-Kupfer and Mareike Ohlberg, ‘China’s digital rise. Challenges for Europe’, Mercator Institute for China Studies, April 2019

- 122: Lawrence Freedman, The Future of War: a history (Hurst: London, 2017); ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘The Future of Warfare’, September 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/sites/default/files/generated/document/en/ESPAS%20Ideas%20Paper%20The%20Future%20of%20Warfare%20FINAL.pdf; Foreign Policy, ‘The Future of War’, Fall 2018

- 123: European Commission, ‘The Age of Artificial Intelligence: Towards a European Strategy for Human-Centric Machine’, 27 March 2018, available at https://ec.europa.eu/epsc/sites/epsc/files/epsc_strategicnote_ai.pdf

- 124: ESPAS Ideas paper, ‘The Future of Work and Workplaces’, May 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-future-work-and-workplaces

- 125: World Economic Forum, ‘5 key trends for the future of healthcare’, 19 January 2018, available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/01/this-is-what-the-future-of-healthcare-looks-like/; The Telegraph, ‘Seven visions of the future of healthcare’, available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/wellbeing/future-health/healthcare-predictions/; World Economic Forum, ‘Technological Innovations for Health and Wealth for an Ageing Global Population’, 2016, available at http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Population_Ageing_Technological_Innovations_Health_Wealth_070916.pdf

- 126: World Economic Forum, ‘How technology is leading us to new climate change solutions’, 29 August 2018, available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/08/how-technology-is-driving-new-environmental-solutions/

- 127: Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, 'The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation?', (Oxford University, 2013), https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf; OECD (2018), 'Automation, skills use and training', https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/automation-skills-use-and-training_2e2f4eea-en; McKinsey Global Institute (2017), 'What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages', https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-organizations-and-work/what-the-future-of-work-will-mean-for-jobs-skills-and-wages#part; Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, 'Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labour Markets', (NBER, 2017), http://www.nber.org/papers/w23285; Bruegel (2018), 'The impact of industrial robots on EU employment and wages: A local labour market approach', http://bruegel.org/2018/04/the-impact-of-industrial-robots-on-eu-employment-and-wages-a-local-labour-market-approach/

- 128: Roderick Parkes, ‘People on the move – The new global (dis)order’, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Chaillot Paper No.138, June 2016, available at https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/people-move-%E2%80%93-new-global-disorder; National Research Council, Beyond Six Billion: Forecasting the World’s Population (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2000), p.39

- 129: Roderick Parkes, ‘Nobody move! Myths of the EU migration crisis’, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Chaillot Paper No.143, December 2017, available at https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/nobody-move-myths-eu-migration-crisis

- 130: ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘Global Trends to 2030: The Future of Migration and Integration’, October 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-future-migration-and-integration

- 131: German Development Institute, ‘More Development – More Migration? The “Migration Hump“ and Its Significance for Development Policy Co-operation with Sub-Saharan Africa’, Briefing Paper 20/2017, available at https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/BP_20.2017.pdf

- 132: François Héran, ‘Europe and the spectre of sub-Saharan migration’, Population & Societies, Number 558, September 2018, available at https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/28441/558.population.societies.migration.subsaharan.europe.en.pdf

- 133: Paul Collier, Exodus. How Migration is Changing Our World, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013) p. 61, p. 123

- 134: Martin Eiermann et al., ‘European Populism: Trends, Threats and Future Prospects’, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, December 2017, available at https://institute.global/insight/renewing-centre/european-populism-trends-threats-and-future-prospects

- 135: Barry Eichengreen, The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 1-13

- 136: More in Common, ‘Attitudes Towards Refugees, Immigrants, and Identity in France’, July 2017, available at https://moreincommon.squarespace.com/france-report; More in Common, ‘Attitudes Towards National Identity, Immigration, and Refugees in Germany’, July 2017, available at https://moreincommon.squarespace.com/germany-report;

- 137: European Parliament, ‘Global Trends to 2035: Economy and Society’, November 2018, p.87 available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/627126/EPRS_STU(2018)627126_EN.pdf

- 138: ESPAS Ideas Paper Series, ‘Global Trends to 2030: New ways out of poverty and exclusion’, January 2019, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu/orbis/document/global-trends-2030-new-ways-out-poverty-and-exclusion

- 139: ESPAS Foresight Reflection Paper Series, ‘Is the Internet Eroding Europe’s Middle Ground? Public Opinion, Polarisation and New Technologies’, March 2018, available at https://espas.secure.europarl.europa.eu%2Forbis%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fgenerated%2Fdocument%2Fen%2FForesight%2520Reflection%2520Polarisation%2520paper_V04.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0Zq4SaQ9AMG7aoGGOEd0qq