Working parents the best protection against child poverty

Children are more likely to live in poverty than adults. Almost twenty million children in Europe, more than 1 child in 5, live below the poverty threshold (poverty rate of 21.1% compared to 16.3% among people over 18 years old). Since the economic crisis, child poverty has increased in most EU countries. This is a worrying trend as the living conditions and the environment in which children are brought up are highly important for their healthy development.

© De Visu / Shutterstock

Children are more vulnerable to the devastating effects of poverty and its long-term consequences than adults are. Hence, specific attention should be accorded to children living in low-income families to guarantee equal opportunities for all children and to break the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage. Living in poverty often means limited access to health care, higher risk of school drop-out and later unemployment and poverty, and not reaching one's full potential in general.

Work intensity in the household and child poverty: a strong link

In a few previous posts here, we have highlighted the importance of women's labour force participation from the perspectives of gender equality and economic progress. Moreover, removing barriers to parents' employment is desirable because of its potential to reduce household poverty in general and child poverty in specific.

Recent decades have seen the generalisation of dual-earnership, that is, when the two adults of the household are working. This means that a double income in a family has become the norm as a result of socio-cultural changes and as a way to make ends meet. Consequently, many single-earner households (including single-parent families), and the children living in them, face a growing risk of poverty.

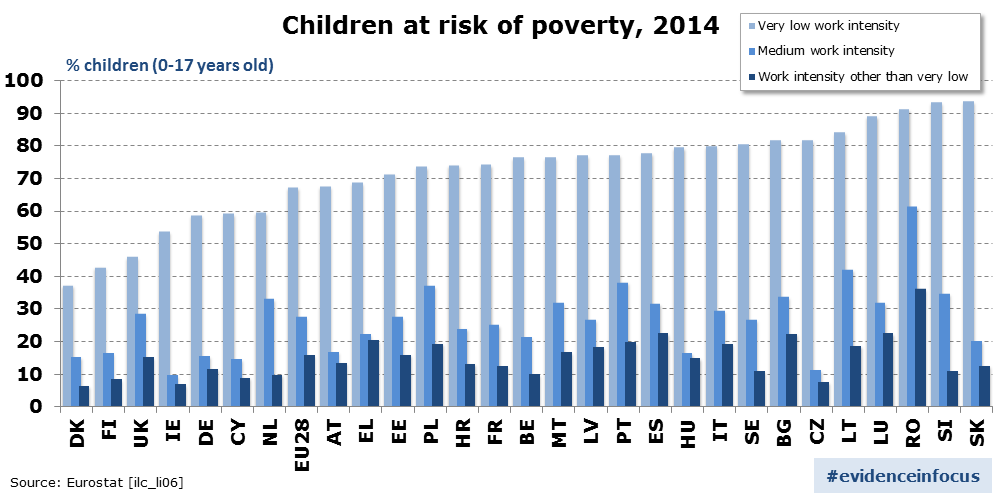

The chart below illustrates the dramatically high poverty risk of children living in households of very low work intensity: 67.2% in the EU. In Slovakia, Slovenia and Romania more than 90% of children living in such families face the risk of poverty. The share is also very high in countries that otherwise perform well in terms of child poverty: 37% in Denmark and 43% in Finland.

Moving from low to medium work intensity (e.g. one of the two parents working) reduces considerably the risk of poverty of children in the EU to 27.5%, while this is still remarkably higher than among children living in households where both parents are working full year. This means that work can play an important role in preventing or lifting people out of poverty.

However, even very high work intensity is not always enough to support the incomes of families with children and eliminate child poverty: 18% of Romanian children and more than 9% of children in Latvia, Lithuania and Luxembourg living in households of very high work intensity are at risk of poverty (EU average 6.3%). While work as 'the best form of social protection' has been given more and more prominence in many countries, welfare systems should also protect children living in households excluded from the labour market and help those who despite working cannot make ends meet.

Note: Work intensity is measured for all individuals aged 18-59 living in the household. Very low work intensity equals to a work intensity below 20% (e.g. in a household of two adults – annual maximum work intensity of 24 months – this would mean that one adult works at most 4.8 months per year) and medium work intensity equals to a work intensity of 45-55% (e.g. in a household of two adults, one adult works full year). At-risk-of-poverty is measured as 60% of median disposable income of the country. Source: Eurostat [ilc_li06].

Note: Work intensity is measured for all individuals aged 18-59 living in the household. Very low work intensity equals to a work intensity below 20% (e.g. in a household of two adults – annual maximum work intensity of 24 months – this would mean that one adult works at most 4.8 months per year) and medium work intensity equals to a work intensity of 45-55% (e.g. in a household of two adults, one adult works full year). At-risk-of-poverty is measured as 60% of median disposable income of the country. Source: Eurostat [ilc_li06].

The role of cash benefits to tackle child poverty

In addition to helping parents combine work and family life, supporting families with cash benefits is necessary. Family benefits form a considerable part of household income in the bottom of the income distribution in many EU countries. For example, in Ireland 40% of the household income in the bottom quintile comes from family benefits, in Hungary 39% and in the United Kingdom 33% (see Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2015, p. 321). Hence, cutting these benefits, as it has happened in several EU countries in recent times, will likely hurt families with already tight budgets the most and contribute to increase child poverty and its long-term negative consequences.

Tackling multidimensional poverty for a better future: employment combined with social protection

Monetary poverty is of course only one aspect of multidimensional poverty affecting children and it should be considered together with other dimensions such as access to education, health care and other services. Therefore, tackling poverty and disadvantage necessitates a holistic approach that integrates children's rights in all policies. Moreover, saving on children-related policies in the short-term may perpetuate intergenerational disadvantage and generate costs associated with unemployment and poverty in the future. Instead, investing in families with children can be a cost-effective way to prevent social problems of tomorrow.

Outcomes for children are an essential factor affecting long-term social and economic development. Investment in childhood is key to tackling the challenges associated with ageing societies in Europe, both in terms of its impact on children when they grow older and for the direct impact on families through income support and services that enable parents to work.

All in all, the one-breadwinner family model no longer appears sufficient to protect families against poverty. The higher the work intensity in the household, the lower is the poverty risk. While other risk factors exist, the labour market situation of parents is a powerful determinant of the conditions in which children grow up and their opportunities in the long run.

It is therefore important to support access to the labour market through good quality childcare, allow flexible working time arrangements for both mothers and fathers and ensure adequately paid jobs. Furthermore, an adequate safety net should also be available for those who fail to participate in the labour market or when working itself is not sufficient to protect families from poverty.

Author: M. Vaalavuo works as a socio-economic analyst in the analytical unit of DG EMPL.

For more information, see our recent review Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2015.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Editor's note: this article is part of a regular series called "Evidence in focus", which will put the spotlight on key findings from past and on-going research at DG EMPL.