Law enforcement: a forgotten determinant of labour law impact

Labour law is the body of rules which regulate the relationships between workers, employers, trade unions, employers' associations and the state. Its aims are manifold, ranging from ensuring workplace protection against accidents and disability to protecting workers and society from the costs and risks associated with dismissals. Labour law can regulate employment contracts, minimum wages, working time, and non-discrimination, amongst other things.

One sub-set of labour law is employment protection legislation (EPL), which defines the limits to the ability of firms to hire and dismiss workers, by setting the requirements to be respected by the employer when dismissing workers and by defining the lawfulness of the dismissal. Labour law is thus a major determinant of how flexibly businesses can adapt their workforces (and wage costs) to changing circumstances.

Labour law determines how economic risks are shared between workers and their employers. If labour law is too lax, businesses can externalise adjustment costs; if it is too strict, employers may be discouraged from hiring. Thus, a good balance needs to be struck between flexibility and protection. But what are the key ingredients of such balance? The chapter on labour law in the recent Employment and Social Development in Europe 2015 analyses one that is often overlooked: the impact of law enforcement.

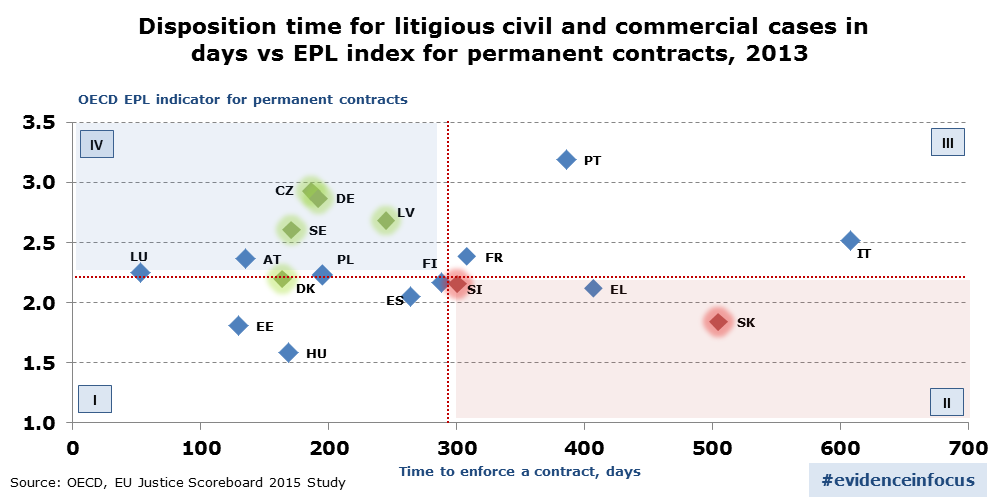

In 2013, the stringency of EPL for permanent contracts, measured by the OECD index of EPL, varied across the EU Member States from 1.6 in the UK (least stringent) to 3.2 in Portugal (most stringent) (Chart, vertical axis). It was above the (unweighted) average of the EU countries for which data was available (the red horizontal line) in Austria, France, Italy, Sweden, Latvia, the Netherlands, Germany, Czech Republic and Portugal.

The role of courts in protecting workers' rights

The enforcement of labour law is important. To be effective, labour law (including EPL) needs to be enforced by recognised authorities. Therefore, well-functioning civil, administrative and labour courts are crucial to settle employment-related disputes. The efficiency of civil justice systems determines how well workers are protected in practice, but also how costly it is to settle disputes between employers and workers.

The efficiency of civil courts can be measured using the so-called 'disposition time' i.e. an estimated average length of civil or commercial trials in days. This indicator shows that the efficiency of civil courts varies considerably across Europe. In 2013, the disposition time ranged from 53 days in Luxembourg to 608 days in Italy and 750 days in Malta (Chart, horizontal axis). The average trial length in the countries for which data are available is above average (the red vertical line) in Slovenia, France, Portugal, Greece, Slovakia and Italy.

In the Chart, the two red lines divide Member States into four groups. Group I represents those for which both the EPL index is low and trial length is below average (e.g. Hungary and Estonia). Group III represents the opposite: both EPL is high and trial length is long (only France, Italy and Portugal fall into this group). The Czech Republic, Latvia, Sweden and Germany in group IV have higher EPL scores but also efficient enforcement, while in group II (including only Slovakia, Greece and Slovenia) the opposite is the case.

Source: EU Justice Scoreboard 2015 Study on the functioning of judicial systems in the EU Member States, carried out by the CEPEJ Secretariat for the Commission, and OECD indicators of EPL. Note: disposition time is defined as the ratio between the number of pending cases at the end of a period and the number of resolved cases during the period, multiplied by 365). Since 2013, several reforms have reduced EPL for permanent contracts across the EU (e.g. in PT). These reforms are not reflected in the Chart.

Source: EU Justice Scoreboard 2015 Study on the functioning of judicial systems in the EU Member States, carried out by the CEPEJ Secretariat for the Commission, and OECD indicators of EPL. Note: disposition time is defined as the ratio between the number of pending cases at the end of a period and the number of resolved cases during the period, multiplied by 365). Since 2013, several reforms have reduced EPL for permanent contracts across the EU (e.g. in PT). These reforms are not reflected in the Chart.

Employers' perceptions of legislation: efficiency of the enforcement matters

This brings us to an important point: Can the efficiency of courts influence employers' perceptions regarding how strict EPL is and how flexible labour markets are? Consequently, can it influence employers' attitudes and decisions regarding whether to hire workers?

Perceived flexibility in hiring and dismissing workers is measured by the World Economic Forum (WEF) indicator which ranks employers' perceptions on a scale between 1 (most rigid) and 7 (least rigid). The WEF indicator ranged from 2.37 in Slovenia to 5.05 in Denmark in the EU.

According to employers' perceptions, flexibility was higher than what the OECD EPL index would suggest in Germany, Sweden and the Czech Republic, all part of group IV and highlighted in green. These four countries have some of the highest OECD EPL index scores but are perceived as relatively flexible by employers.

By contrast, Slovenia and Slovakia, in group II and highlighted in red, are perceived as less flexible than what the OECD EPL index would suggest. In other words, some Member States with a more inefficient resolution of cases are perceived by employers as more rigid than the OECD EPL indicator would suggest, while some Member States with a more efficient resolution of cases are perceived as less rigid than the OECD EPL would suggest.

Putting all the three indicators together, it appears that the efficiency of courts could influence employers' perceptions of labour market flexibility and, in turn, their willingness to hire workers. Our analysis shows that, while more stringent EPL for individual and collective dismissals reduces job finding and dismissal rates and may lead to longer spells of unemployment, the effect is stronger and more significant in Member States where it takes long to resolve court cases including labour disputes. It is smaller and actually not significant for Member States where the trial length is (relatively) short.

One of the key messages from the chapter on Labour Law in the Employment and Social Development in Europe 2015 review is that the efficiency of the judicial system does appear to influence labour markets dynamics. This in turn suggests that when discussing possible labour law reforms improved efficiency of the civil justice system may be similarly important to employers as more flexible labour law rules.

Authors: A. Xavier is the deputy head of unit of Thematic Analysis and F. Lucidi is a policy officer in the unit Employment and Social Aspects of European Semester in DG EMPL.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Editor's note: this article is part of a regular series called "Evidence in focus", which will put the spotlight on key findings from past and on-going research at DG EMPL.