Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - poverty and social exclusion

Data extracted in August 2019. Planned article update: September 2020.

Highlights

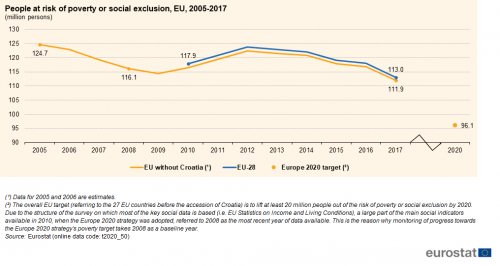

Although the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion fell by 3.1 million between 2008 and 2017, the EU remains far from its Europe 2020 target of reducing this number by 20 million by 2020

(million people)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_50)

This article is part of a set of statistical articles on the Europe 2020 strategy. It provides recent findings on risk of poverty and social exclusion in the European Union (EU).

Full article

General overview

The Europe 2020 strategy is the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs for the current decade. It emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth as a way to strengthen the EU economy and prepare its structure for the challenges of the next decade.

Poverty reduction is a key policy component of the Europe 2020 strategy. By setting a poverty target, the EU has put social concerns on an equal footing with economic objectives. However to achieve the Europe 2020 strategy target to reduce the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion the strategy's other priorities, such as providing better opportunities for employment and education, must also be implemented successfully.

Europe 2020 strategy target on the risk of poverty or social exclusion

The Europe 2020 strategy has set the target of ‘lifting at least 20 million people out of the risk of poverty or social exclusion’ by 2020 compared to the year 2008 [1].

How do poverty and social exclusion affect Europe?

The rate of risk of poverty or social exclusion has reached its lowest point since 2005, yet the target remains distant

In 2017, 113.0 million people, or 22.4 % of the EU population, were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This means roughly one in five people in the EU experienced at least one of the following three forms of poverty: monetary poverty, severe material deprivation or very low work intensity of their household. The rate of risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU over the past decade has been marked by two turning points: in 2009, after which the number of people at risk started to rise because of the delayed social effects of the economic crisis; and in 2012, when this upward trend reversed. By 2017, the number of people at risk had fallen below 2008 levels (see Figure 1), which is the reference year for the Europe 2020 target. Nevertheless, with a gap of about 16 million people, the 2020 target remains at a distance.

Poverty and social exclusion can manifest themselves in various forms. While household income has a big impact on living standards, other aspects, such as access to labour markets and material deprivation, also prevent full participation in society. This is reflected in the three sub-indicators that compose the ‘at-risk-of-poverty or social exclusion rate’ indicator: monetary poverty, severe material deprivation and very low work intensity [2]. Because these sub-indicators tend to overlap and people can be affected by two or even all three of these types of poverty, a person is counted only once in the headline indicator, even if he or she falls into more than one category.

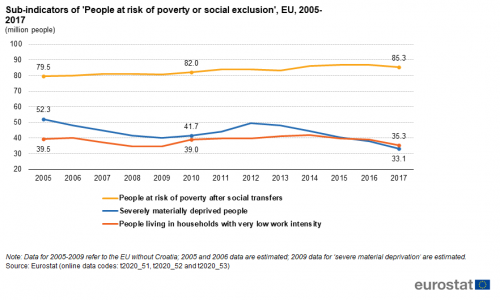

As Figure 2 shows, monetary poverty was the most widespread form of poverty in 2017, with 85.3 million people (16.9 % of the EU population) living at risk of poverty after social transfers. The second most frequent form of poverty was very low work intensity, affecting 35.3 million people or 9.5 % of the EU population aged 0 to 59. At the same time, 33.1 million people or 6.6 % of the EU population were suffering from severe material deprivation.

Over 33 million people, or nearly one-third (29.8 %) of all people at risk of poverty or social exclusion, were affected by more than one dimension of poverty over the same period. Out of these, seven million people, or one in 15 of those at risk of poverty or social exclusion (6.3 %), were affected by all three forms [3].

As shown in Figure 2, the three forms of poverty followed different trends between 2005 and 2017. While monetary poverty has been increasing gradually since 2005, the number of people affected by low work intensity has remained more or less constant until 2016, but declined in 2017. Since 2012 there has been a sharp decline in material deprivation, which was not only strong enough to counteract the rise in monetary poverty, but also led to an overall drop in the risk of poverty or social exclusion (see Figure 1). This means the reduction in material deprivation has been the main driver behind the headline indicator’s improvement since 2012. The decline in the amount of materially deprived people was mainly driven by improvements in a handful of countries [4].

One possible reason for the divergence between monetary poverty and the other two forms of poverty is the different nature of the indicators. While monetary poverty is measured in relative terms, material deprivation and low work intensity are absolute measures. The relativity of monetary poverty means the at-risk rate may remain stable or even rise even though the average or median equivalised disposable income [5] increases. This is because the monetary poverty threshold is set at a specific percentage (60 %) of the median disposable income, which means that if the median income increases, the poverty threshold increases as well. If at the same time the inequality of the income distribution remains unchanged or even increases, the number of people below the poverty line does not decrease. Conversely, absolute poverty measures reflecting a person’s ability to afford basic goods are likely to improve during economic revivals when people are generally financially better off.

(million people)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_50)

(million people)

Source: Eurostat online data codes (t2020_51), (t2020_52) and (t2020_53)

The share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion has decreased in the majority of Member States

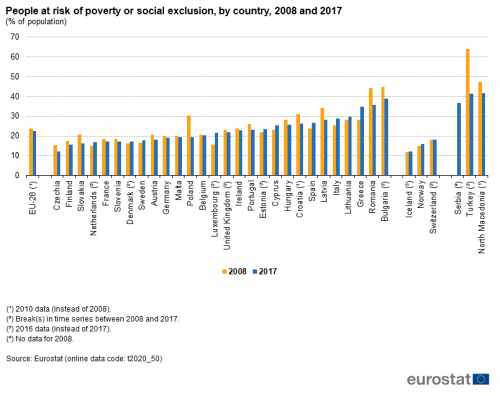

Although on average 22.4 % of the EU population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2017, the levels of individual countries varied widely, ranging from 12.2 % to 38.9 % (see Figure 3). A country’s socioeconomic situation depends on many factors, but much of the current divergence in social outcomes are still a legacy of the economic and financial crisis, as seen in the European Commission’s February 2018 Quarterly Report on the Euro Area. That is to say, Member States linking flexibility in working arrangements with effective active labour market policies and adequate social protection weathered the crisis more successfully (for more information, see the European Commission's Annual Growth Survey 2018 and its Joint Employment Report 2018, and the article on ‘Employment’).

To meet the overall EU target on risk of poverty and social exclusion, Member States have set their own national targets in their National Reform Programmes. As noted in the European Council conclusions from 17 June 2010, Member States are free to set their own targets based on the most appropriate indicators for their circumstances and priorities. In 23 countries the target is expressed as an absolute number of people to be lifted out of the risk of poverty or social exclusion or one or more of its sub-indicators [6]. Of these countries, Czechia, Croatia, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia had already reached their national poverty targets by 2017. On the other hand, the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion has risen in 10 Member States since 2008, pushing them further away from their national targets [7].

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_50)

Which groups are at greater risk of poverty or social exclusion?

Identifying groups with a heightened risk of poverty or social exclusion, and determining the reasons behind this vulnerability, is the key to creating sound policies to fight poverty. Compared with the EU average, some population groups are at a higher risk of poverty or social exclusion. The most affected are women, children, young people, people with disabilities, the unemployed, single-parent households and those living alone, people with lower educational attainment, people born in a different country than the one they reside in, people out of work, and, in a majority of Member States, those living in rural areas.

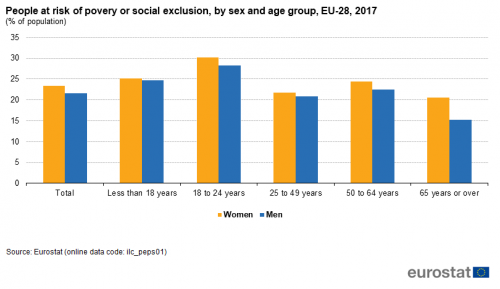

Women and young people are particularly vulnerable to poverty and social exclusion

People's roles and responsibilities within families and in the workplace change throughout their lives and can also be influenced by gender. Thus, it is necessary to consider the breakdown of the headline indicator by age and sex for a complete picture of the structure of risk of poverty or social exclusion.

In 2017 women had a higher rate of risk of poverty or social exclusion than men (the rate for women was 23.3 % compared with 21.6 % for men). Because the definition of households in the context of the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) implies an equal sharing of resources between all members of the household, it is likely that the main drivers behind the gender gap are higher risk-of-poverty rates among single female households — mainly those with dependent children [8]. In a workshop on the main causes of female poverty, the European Parliament’s Directorate General for Internal Policies pointed out that one reason for this persisting gender gap is that single-parent households, which are more often headed by women, are more likely to have very low work intensities compared with other households with children. A comparison of Member States’ performance in the European Semester Thematic Factsheet shows two policy measures that could ease this problem: child and family-support benefits and access to affordable, high-quality childcare.

Between 2010 and 2017, the shares of both men and women being at risk of poverty or social exclusion followed a similar pattern to the overall headline indicator depicted in Figure 1. Even so, compared with 2010, the rate decreased a bit more for women than for men, slightly reducing the gender poverty gap. Most progress in reducing the gender gap was made in the years 2012 to 2015.

The long-term effects of reduced work intensity among women (both single and married) become especially apparent in old age, with the risk-of-poverty-and-social-exclusion gender gap for the age group 65 or over reaching 5.4 percentage points. One explanation for the gender poverty gap among elderly EU residents is that women on average receive a lower pension income than men. As shown in the European Commission’s Pension Adequacy Report, this is mainly due to childcare-related gaps in their employment history and patterns of employment with low pension coverage.

For both men and women, young people below the age of 24 had the highest rates of risk of poverty or social exclusion (29.2 % for 18 to 24-year-olds and 24.9 % for people younger than 18). For more information on this group’s employment situation see the article on ‘Employment’).

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps01)

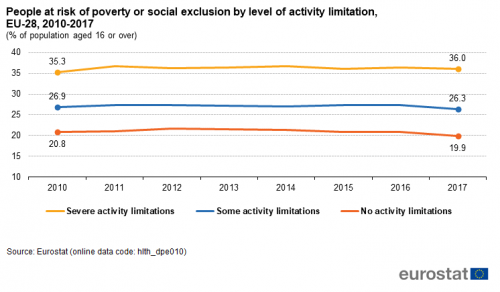

People with disabilities have higher rates of risk of poverty or social exclusion

In 2017, 36.0 % of the EU population aged 16 or more who had severe activity limitations were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, compared with 26.3 % with some activity limitations and 19.9 % of those with no activity limitations (see Figure 5). Despite large country differences, the risk-of-poverty-and-social-exclusion rate among people with activity limitations was higher compared to the overall population in all Member States.

While the overall risk-of-poverty-and-social-exclusion rate fell after 2012, the rate of those with activity limitations remained stable. Some of the main challenges that people with disabilities face are limited access to quality education from an early age and impeded access to the labour market. The integration of people with disabilities into the labour market has proven especially difficult in the wake of the financial crisis (for more Information see the Progress Report by the European Commission on its European Disability Strategy).

The difference between risk of monetary poverty before and after social transfers reveals the importance of social transfers to people with activity limitation. Before social transfers, 68.1 % [9] of people suffering from some or severe activity limitations were at risk of monetary poverty in 2017, but after social transfers this rate was reduced to 20.5 % [10] across the EU [11].

(% of population aged 16 or over)

Source: Eurostat online data code (hlth_dpe010)

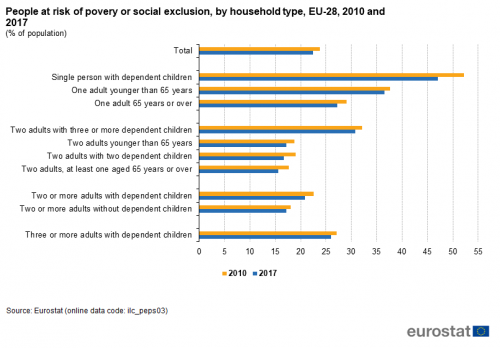

Single parents face the highest risk of poverty or social exclusion

In 2017, 47.0 % of single people with one or more dependent children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This was just over twice the average rate and higher than for other household types. However, this group also experienced the largest decline in the percentage at risk since 2010 when the rate was 52.2 % and well over double the average.

Figure 6 shows that in general households with only one adult — both with and without children — and households with many children are at a higher risk of poverty or social exclusion. In single-adult households there is no partner to help cushion temporary disruptions such as unemployment or sickness. Also, many such households are made up of young unemployed people or pensioners — often women — which have a higher-than-average risk of poverty or social exclusion [12]. Single parents also face the challenge of being both the primary breadwinner and caregiver for the family. The group with the lowest risk of poverty rate in 2017 was that of households with two adults where at least one person was aged 65 years or over.

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps03)

People with low educational attainment are three times more likely to be at risk than those with tertiary education

In 2017, 34.3 % of people with at most lower secondary educational attainment were at risk of poverty or social exclusion (see Figure 7). In comparison, only 11.0 % with tertiary education were in the same situation. This shows that the least-educated people were three times more likely to be at risk than those with the highest education levels (also see the article on ‘Education’). This is also reflected in the data on employment, which show that the likelihood of being employed rises in line with educational level (see the article on ‘Employment’, or the Education and Training Monitor 2017 of the European Commission for more information).

(% of population aged 18 and over)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps04)

The risk of poverty or social exclusion due to low education is passed on to the next generation

An important aspect to consider when analysing the overall number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion is the transmission of disadvantage from one generation to the next.

At 9.5 %, children (aged 18 or less) of parents who obtained tertiary education had about the same risk of poverty or social exclusion rate as the overall population with the highest educational level in 2017. In contrast, the situation was especially grim for children of parents with at most pre-primary and lower secondary education. While around a third of the overall population with the lowest educational attainment was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2017, this rate was almost twice as high, at 62.9 %, for children of parents in this group. This implies that the risk of poverty or social exclusion particularly affects families where parents could not benefit from an extensive education.

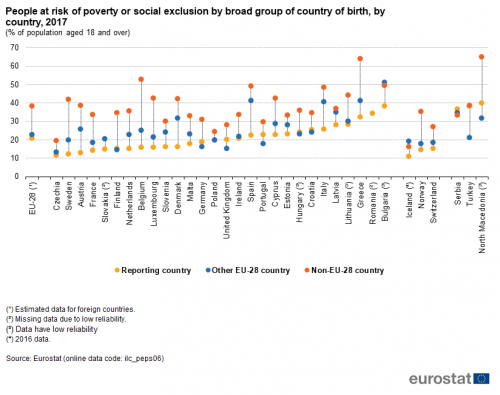

People from outside the EU are generally worse off than people living in their home country

In 2017, people living in the EU but born in a non-EU country had a 38.3 % at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion rate. The rate was lower for people born in an EU-country other than the one they were living in, at 22.7 %. Among the people who resided in their country of birth, 20.7 % were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Thus, people born outside the EU had a twice higher rate of being at risk of poverty or social exclusion compared with native residents. Compared to migration from a country from outside the EU, migration within the EU bears a far smaller risk of poverty or social exclusion.

The ‘poverty origin gap’ can arise due to a number of factors, such as the level of education, labour market access and employment status of foreign citizens residing in a given Member State. Difficulties with labour market access among foreign citizens can be due to migration specific work obstacles: problems with credential recognition, language and communication barriers, or discrimination on social and religious grounds (for more information, see the Eurostat article on First and second-generation immigrants — obstacles to work and the Migrant integration statistics). Furthermore, the socioeconomic outcomes of the foreign-born population may also reflect the different reasons for migrating to a specific country. For instance, in many EU countries a large share of non-EU migrants did not come to their host country primarily for work, but rather for family or humanitarian reasons (see Employment and Social Development in Europe 2018 and the International Migration Outlook 2018 by the OECD).

Between 2010 and 2017 the risk of poverty or social exclusion rate increased for those living in a country other than their country of birth, both for those from outside the EU and those from inside the EU.

(% of population aged 18 and over)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps06)

People in rural areas have slightly higher rates of risk of poverty or social exclusion

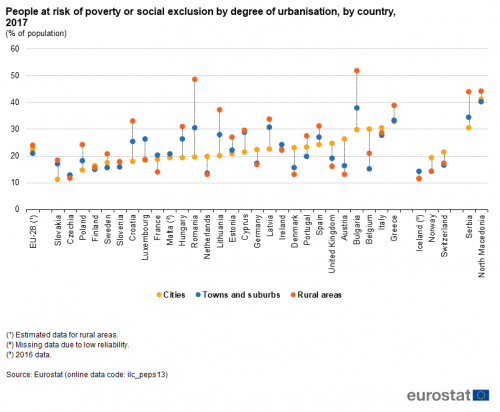

On average, EU residents in rural areas were slightly more likely to live at risk of poverty or social exclusion than those in urban areas (23.9 % in rural areas compared with 22.6 % in cities) in 2017 (see Figure 9). Those living in towns or suburbs were the least likely to be at risk (21.0 %). Despite the overall EU average showing higher rates of risk of poverty or social exclusion in rural areas, in some northern, central and western Member States, people residing in urban areas were more often affected than in rural areas.

In a study report on poverty and social exclusion in rural areas, the European Commission identified four main categories of problems that characterise rural areas in the EU and determine the risk of poverty or social exclusion: demography (for example, the exodus of residents and the ageing population in rural areas), remoteness (such as lack of infrastructure and basic services), education (for example, lack of preschools and difficulty in accessing primary and secondary schools) and labour markets (lower employment rates, persistent long-term unemployment and a greater number of seasonal workers). At the same time, even if urban areas are often characterised by high concentrations of economic activity, they are also characterised by a range of social inequalities, where especially the cost of living can contribute to the risks of poverty [13].

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps13)

Data sources

Indicators presented in the article:

- People at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE) (t2020_50)

- Breakdown by age and sex (ilc_peps01)

- Breakdown by level of activity limitation (hlth_dpe010)

- Breakdown by household type (ilc_peps03)

- Breakdown by educational attainment level (ilc_peps04)

- Breakdown by broad country of birth (ilc_peps06)

- Breakdown by degree of urbanisation (ilc_peps13)

- People at risk of poverty after social transfers (AROP) (t2020_52)

- Severely materially deprived people (t2020_53)

- People living in households with very low work intensity (t2020_51)

Context

Poverty and social exclusion harm lives and limit the opportunities for people to achieve their full potential by affecting their health and well-being and lowering educational outcomes. This, in turn, reduces their ability to lead a successful life and further increases the risk of poverty. Without effective educational, health, social, tax-benefit and employment systems, the risk of poverty is passed on from one generation to the next. This causes poverty to persist, creating more inequality that can lead to the long-term loss of economic productivity from whole groups of society [14] and hamper inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

To prevent this downward spiral, the European Commission has made ‘inclusive growth’ one of the three priorities of the priorities of the Europe 2020 strategy. It has set a target to lift at least 20 million people out of the risk of poverty or social exclusion by 2020. To further reinforce the social dimension of the EU, the European Pillar of Social Rights has been jointly signed by the European Parliament, the Council and the European Commission.

To reach the Europe 2020 poverty goal, particular focus will need to be placed on groups that are at high risk of poverty or social exclusion. With the Social Investment Package, the European Commission has set forth an integrated policy framework aiming to reach out to various vulnerable target groups, for example, with a specific recommendation on on Investing in children: breaking the cycle of disadvantage. Also, between 2014 and 2020, at least 20 % of the European Social Fund is earmarked for measures combating poverty and social exclusion. The Commission’s Reflection paper ‘Towards Sustainable Europe by 2030’ also states that the transition towards sustainability should be socially fair and inclusive, which requires investment in effective and integrated social protection systems.

By setting a poverty target, the EU has put social concerns on an equal footing with economic objectives. However, to achieve the Europe 2020 strategy target to reduce the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion, the strategy’s other priorities, such as providing better opportunities for employment and education, must also be implemented successfully (see the see the articles on ‘Employment’ and ‘Education’

Direct access to

- Towards robust quality management for European Statistics - Communication from the Commission COM(2011) 211 final

- Regulation (EC) No 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

Notes

- ↑ Due to the structure of the survey on which most of the key social data is based (EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions), a large part of the main social indicators available in 2010, when the Europe 2020 strategy was adopted, referred to 2008 as the most recent year of data available. This is why 2008 data for the EU without Croatia are used as the baseline year for monitoring progress towards the Europe 2020 strategy's poverty target. Since 116.1 million people were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU without Croatia in 2008, the target value to be reached is 96.1 million by 2020.

- ↑ The indicator ‘very low work intensity’ is limited to people aged 0 to 59. People over the age of 59 are considered at risk of poverty or social exclusion only if the criteria of one of the two dimensions ‘monetary poverty’ or ‘severe material deprivation’ are met.

- ↑ The year of reference differs for the three sub-indicators. The risk of poverty after social transfers and whether or not someone lives in a household with very low work intensity are based on data from the previous year. The extent to which an individual is severely materially deprived is determined based on information from the year of the survey. Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_pees01)). For a more detailed analysis of the different forms of poverty see Eurostat (2019), Sustainable development in the European Union. Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2019 edition, chapter on SDG 1 ‘No poverty’.

- ↑ For a more detailed analysis of the different forms of poverty see Eurostat (2019), Sustainable development in the European Union. Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2019 edition, chapter on SDG 1 ‘No poverty’.

- ↑ The equivalised disposable income refers to the financial means a household has left for saving and spending. It is calculated by taking the entire income of a household and dividing it by the weighted household size, where each household member receives a weight depending on their age.

- ↑ This corresponds to the base year also used for the overall EU target. Germany and Sweden use targets based on different forms of unemployment, Ireland defined a combined poverty target, the Netherlands aims to reduce the amount of jobless households, and the UK based its numerical targets on a nationally launched Child Poverty Act. European Commission (2015), Social Europe — Aiming for inclusive growth. Annual report of the Social Protection Committee on the social situation in the European Union (2014), Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 162–461.

- ↑ For a more detailed analysis of the different forms of poverty see Eurostat (2019), Sustainable development in the European Union. Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2019 edition, chapter on SDG 1 ‘No poverty’.

- ↑ Given that the data does not reveal systematic differences in the risk of poverty or social exclusion between single female and single male households without dependent children, the gender gap is expected to be caused by single households with dependent children.

- ↑ Eurostat (online data code: (hlth_dpe030)).

- ↑ Eurostat (online data code: (hlth_dpe020)).

- ↑ To assess the importance of social transfers, the analysis focuses on the sub-indicator ‘at risk of poverty’ without the dimensions of material deprivation and very low-work intensity.

- ↑ European Centre (2008), European Centre, Poverty Across Europe: The latest evidence using the EU-SILC Survey.

- ↑ Eurostat (2016), Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs — executive summary.

- ↑ OECD (2017), Understanding the Socio-Economic Divide in Europe, Background Report.