Archive:People in the EU - statistics on geographic mobility

Data extracted in November and December 2017

This article is outdated and has been archived - for recent articles on Population see here.

Highlights

In 2012, Europeans living in cities (21 %) were more likely to move than those living in rural areas (13 %).

In 2016, 73 % of the EU's native-born populations lived in their own homes, compared with 48 % of residents born in other EU countries and 4 % of residents born outside the EU.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hcmp05)

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Archive:People in the EU: who are we and how do we live?; it presents a range of statistics covering movements in and around the European Union (EU), and focuses principally on people who recently moved home.

A paper edition of the publication was released in 2015. In late 2017, a decision was taken to update the online version of the publication (subject to data availability). Readers should note that while many of the statistical sources that have been used in People in the EU: who are we and how do we live? have been revised since its initial 2015 release, this was not the case for the population and housing census, as a census is only conducted once every 10 years across the majority of the EU Member States. As a result, the analyses presented often jump between the latest reference period — generally 2015 or 2016 — and historical values for 2011 that reflect the last time a census was conducted.

Full article

General overview

The EU’s population is increasingly mobile: while most people only move around the EU on a temporary basis for holidays (see the end of this article for more details) or business trips, a small but growing proportion of Europeans relocate to other EU Member States on a (semi-) permanent basis.

The free movement of persons constitutes one of the fundamental freedoms of the internal market, and is enshrined in law (Article 45 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and subsequent secondary legislation). As such, citizens of EU Member States, together with their immediate family — spouses/registered partners, children, and dependent parents or grandparents — are entitled to:

- look for a job in another EU Member State;

- work in another EU Member State without a work permit;

- live in another EU Member State while working or once they have retired.

An article on Archive:Home comforts — housing conditions and housing characteristics highlights that many people spend a considerable proportion of their time at home, and give considerable weight to their living conditions when asked to determine their quality of life.

Moving home

Residential mobility — movements from one place of residence to another — may be viewed in the context of each individual’s journey through life, whereby there are a number of steps that often result in people moving home. One of the biggest decisions is usually that of leaving the parental home: thereafter, other major life events such as deciding to live with someone else or having children also impact on people’s decisions over where they live and the type of dwelling they would like to live in. A range of additional factors also impact on residential mobility, such as the location of higher education establishments, career opportunities, retirement options, or the availability and price of dwellings for rent or purchase.

A quite recent development is the increased numbers of students and retired people who moved country. The former have been encouraged by, among others, EU programmes to support education and training, which allow students to improve their language skills and benefit from learning in an inter-cultural environment. Retirement migration is an increasingly popular form of mobility for Europeans during the later stages of their lives, as retirement destinations have become more diverse, extended beyond the local, regional and even national level to involve international localities, particularly in southern Europe.

Populations on the move by tenure status

In 2012, residential mobility peaked in the Nordic Member States and the United Kingdom

According to an ad-hoc module that formed part of the EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) survey in 2012, some 17.8 % of the EU-28’s population moved home during the five-year period up to 2012. The highest mobility rates were recorded in the Nordic Member States: some 40.2 % of the Swedish population moved during this period, while around one third of the population in Denmark (32.9 %) and Finland (31.9 %) moved home; the United Kingdom (30.8 %) was the only other Member State to record a share above 30 %. At the other end of the range, people tended to be less mobile in the southern and eastern EU Member States, for example, fewer than 5 % of the population moved in Croatia, Bulgaria and Romania during the five-year period up to 2012.

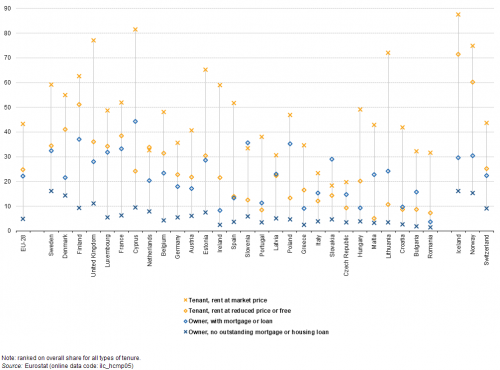

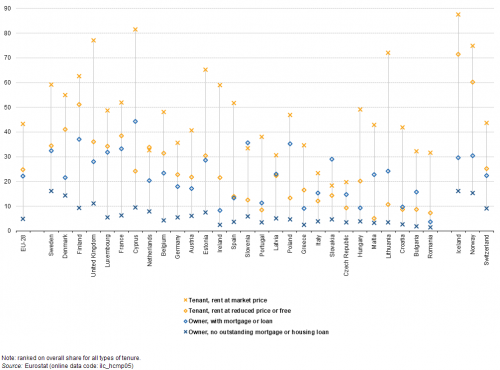

Tenants renting at market prices had the highest degree of mobility in 2012

Figure 1 shows an analysis for the proportion of people moving home during the five-year period up to 2012 by tenure status. Private tenants (people who rent their accommodation at market prices) were more likely to move home than homeowners: across the EU-28, some 43.3 % of private tenants moved during the five-year period up to 2012, this share was almost twice as high as that recorded among homeowners with a mortgage (22.1 %).

There were 10 EU Member States where more than half of the population in private rental accommodation moved during the five-year period up to 2012. These high degrees of mobility peaked in Cyprus (81.6 %), the United Kingdom (77.1 %) and Lithuania (72.1 %) which may reflect, at least to some degree, relatively relaxed regulatory environments for renting or flexible labour markets. By contrast, lower degrees of residential mobility may be recorded in those rental markets characterised by more complex regulatory environments, as controls on rental prices or the length of contracts may ‘lock-in’ existing tenants. The lowest shares of residential mobility among those renting at market prices were recorded in Italy, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, where around one fifth of this subpopulation moved during the five-year period up to 2012.

Home ownership and social housing tended to result in lower levels of mobility in 2012 …

In the EU-28, more than one fifth (22.1 %) of all homeowners with a mortgage or housing loan had moved home during the five-year period up to 2012. This lower level of residential mobility among homeowners — compared with those living in private rental accommodation — may, at least in part, be explained by the higher transaction costs that are generally associated with buying or selling a property. These charges, which may act as a barrier to mobility, include registration costs, sales taxes, legal and notary fees, as well as estate agent fees. There were 10 EU Member States where more than one quarter of all homeowners with a mortgage had moved during the five-year period up to 2012; this share rose to 35-37 % in Poland, Slovenia and Finland, and peaked at 44.3 % in Cyprus.

By contrast, only 4.8 % of EU-28 homeowners with no outstanding mortgage or housing loan moved during the five-year period up to 2012. These figures also suggests that residential mobility may be lower in those EU Member States that are characterised by high levels of home ownership, while those economies with a more established rental market may be characterised by higher degrees of mobility. There were only three EU Member States where more than 1 in 10 homeowners without a mortgage or housing loan had moved during the five-year period up to 2012: Sweden (16.2 %), Denmark (14.3 %) and the United Kingdom (11.1 %).

… although this was not the case for those living in reduced price or free accommodation in Denmark and the Netherlands

Almost one quarter (24.8 %) of EU-28 tenants with reduced or free rent (for example, those living in social housing) moved home during the five-year period up to 2012; this could be contrasted with a 43.3 % share for private tenants in rental accommodation. This gap between the two types of tenants was particularly pronounced in Lithuania and Cyprus, where the proportion of tenants renting at market prices who moved during the five-year period up to 2012 was 61.3 and 57.4 percentage points higher than among those renting at a reduced price or free.

By contrast, the degree of mobility among tenants renting at reduced prices or free was particularly high in Finland (51.2 %), where more than half of those concerned moved during the five-year period up to 2012. The Netherlands was the only EU Member States where residential mobility was higher for tenants living in reduced price or free accommodation (33.8 %) compared with tenants living in private rented accommodation (32.6 %).

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hcmp05)

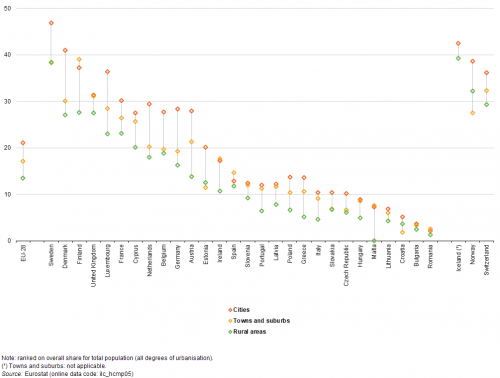

Populations on the move by degree of urbanisation

In 2012, Europeans living in cities were more likely to move than those living in rural areas

Figure 2 (also derived from the ad-hoc housing module that formed part of EU-SILC) provides an alternative analysis of those persons who moved during the five-year period up to 2012, with an analysis by degree of urbanisation. It shows that across the EU-28, there was a higher likelihood that people living in cities (21.1 %) had moved during the five-year period up to 2012 than those living in rural areas (13.5 %). This pattern held in each of the EU Member States: in Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, Germany and the Netherlands the share of city-dwellers having moved during the previous five years was at least 10 percentage points higher than the share recorded among people living in rural areas.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hcmp05)

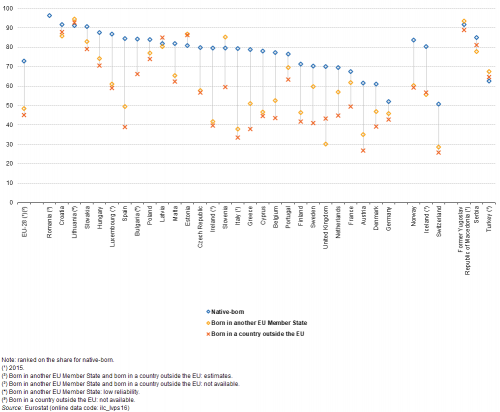

Home ownership by country of birth

In 2016, the highest levels of home ownership were recorded among native-born populations

According to EU-SILC, almost three quarters (73.0 %) of the EU’s native-born population (aged 18 years and over) was living in an owner-occupied home in 2016. This share was considerably higher than the corresponding shares recorded for residents born in other EU Member States (48.4 % were homeowners) or countries outside of the EU (45.2 % were homeowners), see Figure 3.

It is interesting to note that there were considerable differences between the EU Member States in relation to the share of their native-born populations who were homeowners. In 2016, in excess of 90 % of the native-born population in Romania, Croatia, Lithuania and Slovakia lived in an owner-occupied home, a share that fell to between 60.0-70.0 % in Denmark, Austria, France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. However, by far the lowest share of native-born persons living in owner-occupied homes was recorded in Germany, at 52.1 %; note there is a thriving rental sector in Germany, which may be promoted by increased security of tenure for private tenants (for example, an unlimited duration for contracts).

This pattern of higher home ownership for native-born residents was repeated in most of the EU Member States and was particularly pronounced in Italy, Ireland (both 2015 data), Spain, Greece, the United Kingdom, Cyprus and Austria. By contrast, the proportion of homeowners in Estonia and Lithuania was higher among foreign-born residents (for people born in another EU Member State as well as for people born in a country outside the EU) than it was for native-born residents. In Slovenia the proportion of homeowners was higher for residents born in another EU Member State than it was for native-born residents, while in Latvia the share of homeowners was higher among residents born in a country outside the EU than it was for native-born residents.

In most of the EU Member States, home ownership was more common among people born in another EU Member State than it was for people born in a country outside the EU. Subject to data availability, there were only three exceptions to this pattern in 2016, with higher shares of home ownership among people born outside the EU in Croatia, Latvia and, in particular, in the United Kingdom. In the latter, the proportion of people born outside the EU who lived in an owner-occupied home was 13.0 percentage points higher than the share among people born in another EU Member State.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvps16)

European residents on the move

In 2011, almost 32 million persons in the EU moved home during the course of the 12-month period prior to the census

Having established some general patterns of mobility and home ownership across the EU Member States, this next section looks in more detail at those who moved home during the 12-month prior to the population and housing census conducted in 2011. There were almost 32 million persons in the EU (excluding Bulgaria, for which data are not provided) who changed their usual residence during this period: of these, over 7 million persons moved in each of France and the United Kingdom (22.7 % and 23.4 % of the EU total).

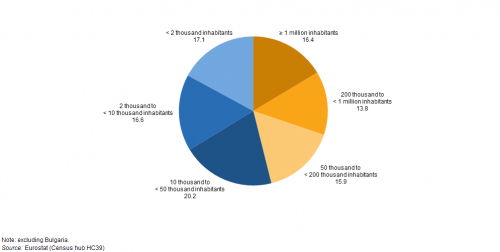

Figure 4 shows the distribution of EU residents who moved, according to the size of the locality to which they moved. At opposite ends of the spectrum, there were roughly equal shares for those who moved into localities with at least one million inhabitants (16.4 % of the total number of persons who moved during the year prior to the census) and those who moved into localities with fewer than 2 thousand inhabitants (17.1 %).

Socioeconomic characteristics of residents who moved in the 12-month period prior to the census

Having examined the flows of people moving into and around the EU-28, this next section turns to look at some of the socioeconomic characteristics of those residents who moved during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census (irrespective of where they came from).

In 2011, people in the labour market had a higher propensity to move home …

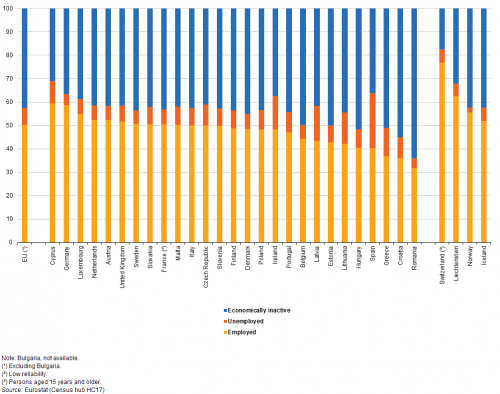

Figure 5 shows that approximately half (50.2 %) of the EU-28 population who moved during the 12-month period prior to the census were in employment, while 42.5 % were economically inactive (including those in education or in retirement) and 7.3 % were unemployed. These figures can be compared with totals for the whole of the EU-28 population in 2011, when 43.6 % of the population were employed, 4.7 % were unemployed, and 51.8 % were inactive. As such, those in employment and unemployment had a higher propensity to move home than the inactive population.

In Cyprus, Germany and Luxembourg, people in the labour force (the employed and unemployed) accounted for more than 6 out of 10 persons who moved during the 12-month period prior to the census. This suggests that new job opportunities were one of the main drivers for changing residence in these three Member States. In Spain, Latvia, Ireland, Lithuania and Greece, the unemployed accounted for more than 1 in 10 persons who moved home during the 12-month period prior to the census; note that many of these economies were particularly affected by the global financial and economic crisis, suggesting that unemployed persons may have been relocating in search of a new job or because they could no longer afford to pay for their home, be it a rental property or owner-occupied with a mortgage.

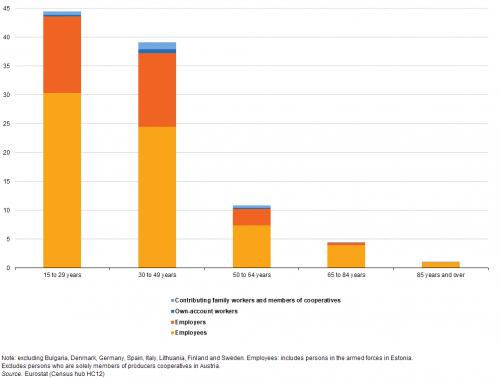

… while the likelihood of moving was also higher among younger persons

An analysis by employment status and by age — as shown in Figure 6 — provides evidence that the likelihood of someone moving home generally decreases as a function of their age; this information is also derived from the population and housing census. People aged 15-29 years accounted for 44.4 % of the total number of employed persons who moved home in the EU-28 during the 12-month period prior to the census. Economic theories of mobility are largely based on the assumption that people try to maximise their net gains (their increased earnings potential minus the costs of moving); therefore, younger persons tend to have a greater incentive to move, as their total possible earnings are greater, given they have a longer working life ahead. Such differences may also reflect, in part, the relatively precarious nature of employment for many people in this age group, as well as a higher probability that they will face changes to their personal situation — for example, leaving the parental home, deciding to live with someone else, or starting a family. More detailed information in relation to these aspects is provided in an article on People in the EU - statistics on household and family structures.

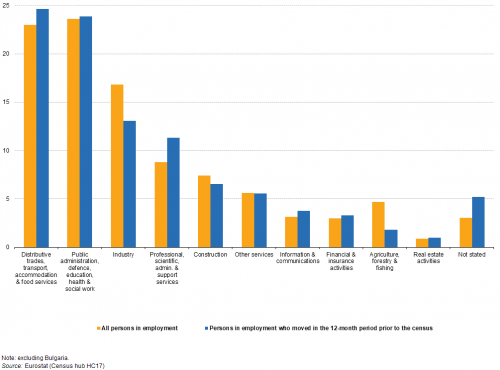

In 2011, people in occupations and economic activities associated with higher degrees of educational attainment were more mobile

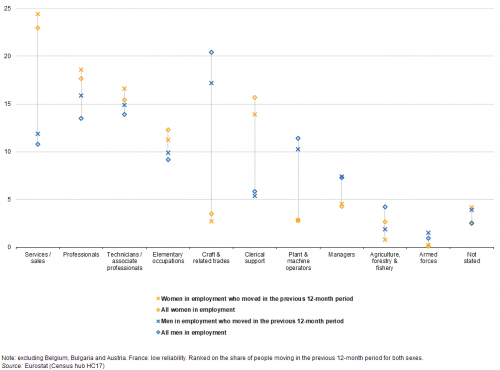

The information presented in Figures 7 and 8 — also from the population and housing census — provides an analysis of the proportion of residents who moved home during the 12-month period prior to the census, by occupation and by economic activity (as defined by NACE); in both cases the information for people moving home is compared with that for all persons in employment.

Figure 7 shows that the likelihood of someone moving home was higher for a range of occupations associated with higher levels of educational attainment, for example, professionals and technicians/associate professionals were more likely to move, whereas the propensity to move was lower among those with craft and related trades, agriculture, forestry and fishery, or clerical support occupations.

It is also interesting to note that this pattern was repeated for men and for women. Indeed, people employed in services/sales, as professionals, technicians/associate professionals and managers, or in the armed forces were more mobile, whereas people with occupations such as in agriculture, forestry and fishing (for both sexes), crafts and related trades and plant and machine operators (particularly among men) and clerical support (particularly among women) tended to be less mobile.

Figure 8 presents a similar analysis by economic activity and confirms the results observed in Figure 7 insofar as those working in traditional activities such as industry, agriculture, forestry and fishing or construction tended to move less often than expected (when analysing their overall share in total employment), while people employed in professional, scientific, administrative and support services, distributive trades, transport, accommodation and food services, or information and communication services were more likely to move. Note that many services are omnipresent across local, regional and national economies, whereas specific industrial or agricultural activities may only be located in a few, specialised regions.

Furthermore, there is some evidence to support the view that people with more developed skills and competencies have a higher propensity to consider employment opportunities over a wider geographical area: changing region or country may be more part of the professional culture of certain highly-educated workforces in areas such as professional and scientific services or information and communication services.

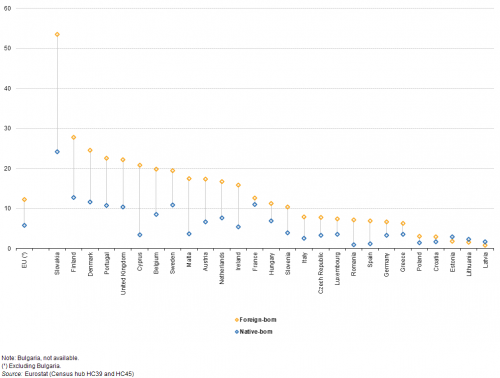

In 2011, foreign-born residents were more than twice as likely to move as native-born residents …

Within the EU (again excluding Bulgaria), foreign-born residents were generally more mobile than native-born residents. In 2011, the proportion of foreign-born residents who moved during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census was 12.3 %, which was more than twice as high as the share recorded for the native-born population (5.8 %). These differences may be linked to geographic and labour market mobility of foreign-born residents, and a range of different factors, including: a higher proportion of foreign-born residents live in rental accommodation; migrants tend to be relatively young and willing to occupy temporary, low-skilled or part-time jobs — often below their educational qualifications or skills — in order to enter or move within the labour market; migrants may engage in circular migration, whereby they move between different EU Member States or between their home country and other EU Member States (for example, in order to obtain seasonal work).

In 2011, this pattern of foreign-born residents being more likely to move home during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census was repeated in all but three of the EU Member States. The three Baltic Member States were the only exceptions to this rule, as their native-born populations were more likely to have moved than the foreign-born population; note also that the overall share of the total population who moved home during the 12-month period prior to the census was very low in all three Baltic Member States.

In Malta and Spain, foreign-born residents were around five times as likely to move as the native-born population, while this ratio rose to around 6 : 1 in Cyprus, and peaked at 7.5 : 1 in Romania. The largest differences (in percentage point terms) between the shares of foreign-born and native-born residents who moved home during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census in 2011 were recorded in Slovakia (where the share for foreign-born residents was 29.2 points higher), Cyprus (17.4 points) and Finland (15.0 points).

Across the EU (excluding Bulgaria), there was almost no difference in the residential mobility of foreign-born residents between those born in another EU Member State (12.2 % moved during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census) and those born in a country outside the EU (12.3 % had moved). The individual EU Member States were almost equally divided, insofar as 14 reported a higher proportion of residential mobility among those born in a country outside the EU, while mobility was higher in 13 others among the subpopulation born in another EU Member State.

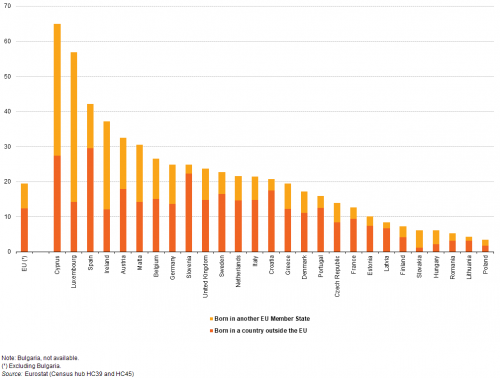

… while foreign-born residents accounted for almost one in five persons in the EU who changed residence

Figure 10 is also based on information from the population and housing census and analyses the relative share of foreign-born residents in the total number of persons who moved home during the 12-month period prior to the census; these figures reflect, at least to some degree, the stock of foreign-born residents already in the EU as a result of different historical waves of migration, as well as more recent migrant flows during the year prior to the census.

In 2011, residents born in a country outside the EU accounted for 12.3 % of the total number of persons who moved home during the 12-month period prior to the census; the corresponding share for residents born in another EU Member State was 7.2 %. As such, all foreign-born residents together accounted for almost one in five persons who moved in the EU during the 12-month period prior to the census.

Foreign-born residents accounted for more than half of the total number of residents who moved in Cyprus (65.0 %) and Luxembourg (56.8 %); in both cases the majority of the foreign-born residents moving were born in another EU Member State. Ireland, Slovakia, Malta and Hungary were the only other EU Member States where residents born in another EU Member State accounted for a higher proportion of the total number of persons who moved home than residents born in a country outside the EU.

By contrast, almost one third (29.5 %) of the total number of residents who moved home in Spain during the 12-month period prior to the census were born in a country outside of the EU (a majority of these were from the Caribbean, Central or South America), while around one quarter of the total number of residents in Cyprus (27.4 %) and Slovenia (22.3 %) who moved home were born outside the EU (for the former the majority were born in Asia, while for the latter the majority were born in other countries in Europe that are not EU members).

More detailed residential mobility statistics

Although the focus of analysis so far has been on national and international mobility patterns, information from the population and housing census may be used to show that the vast majority of people who moved in the EU during the 12-month period prior to the census did so within a very restricted geographical area.

Indeed, residential and labour market mobility is generally quite low in the EU, especially in light of the often considerable labour market imbalances between EU Member States: for example, in 2011, unemployment rates ranged from a high of 21.4 % in Spain to a low of 4.6 % in Austria, while annual net earnings for a married couple with two children (where both parents earned the average wage) ranged from a high of EUR 116 230 in Belgium to a low of EUR 10 230 in Bulgaria. This apparent lack of mobility may be explained, to some degree, by: a lack of language skills that prevent people moving to another country; difficulties in comparing educational and professional qualifications; a lack of access to credit (especially in the aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis); a variety of cultural and institutional barriers; or the social costs of leaving one’s family, friends, colleagues and local community behind. These links between housing, mobility and the labour market are explored further in the section below.

While interpreting the analysis that follows it is important to note there are considerable differences in the land area of each EU Member State: for example, a change of residence from Bremen in the north of Germany to München in the south equates to a move of almost 800 km, while the distance between the Austrian capital of Vienna and the Slovak capital of Bratislava is approximately one tenth of this, as is the distance between the Finnish capital of Helsinki and the Estonian capital of Tallinn.

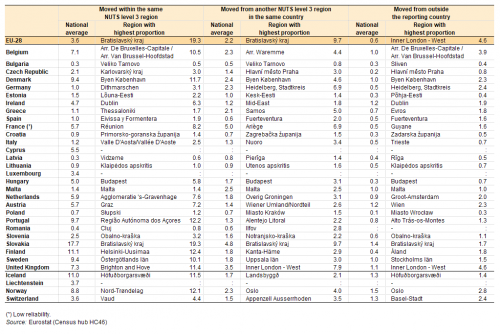

In 2011, the vast majority of Europeans either did not move or moved within the same region

Table 1 shows that 6.4 % of EU-28 population (32.0 million residents) moved home during the year prior to the census in 2011: 3.6 % (or 18.1 million residents) from within the same NUTS level 3 region; 2.2 % (11.0 million residents) from another region of the same country; and 0.6 % (2.9 million residents) from abroad.

As noted above, the highest absolute numbers of people moving home were recorded in France and the United Kingdom. Within the latter, there was a relatively high propensity for residents to move within the same NUTS level 3 region (7.3 % of the population of the United Kingdom, approximately double the EU average), although higher shares were recorded in Denmark and Sweden (both 9.4 %), Portugal (9.7 %), Finland (11.1 %) and particularly Slovakia (17.7 %). In France, while the share of the population who moved within the same NUTS level 3 region (5.7 %) was higher than the EU-28 average, almost the same proportion of residents (5.0 %) moved between different NUTS level 3 regions within France; this was the highest share of residents moving between different NUTS level 3 regions among any of the EU Member States.

The 2.9 million residents who moved from outside the reporting country (note these persons could be foreign-born or returning national-born persons) accounted for 0.6 % of the EU-28 population in 2011. Their relative share rose to 1.0 % in Belgium, Denmark, Malta and Sweden, 1.1 % in the United Kingdom, 1.2 % in Ireland and Austria, and peaked at 1.4 % in Slovakia. In absolute terms, there were almost 690 thousand residents in the United Kingdom who moved from abroad during the previous 12 months (23.5 % of the EU-28 total), while the next highest totals were recorded in Germany (almost 400 thousand) and France (almost 315 thousand).

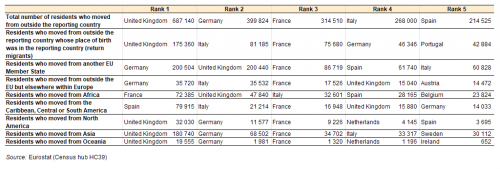

In 2011, around 200 thousand residents moved from other EU Member States to each of Germany and the United Kingdom

Table 2 focuses on those residents who moved from outside one of the reporting countries to set-up a new home. It shows the most popular destinations (at the level of EU Member States) for new residents arriving from abroad during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census.

The largest flows of residents from other EU Member States were into Germany and the United Kingdom (with just over 200 thousand persons moving to each), reflecting in part the size of these two economies, but also their economic situation in the aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis, as well as the relatively high proportion of EU citizens who are able to speak English and to a lesser extent German.

The most popular destinations for residents arriving from other continents were often characterised by historical/colonial, cultural or linguistic ties: for example, the largest number of people moving from Africa set-up home in France, the largest numbers from the Caribbean, Central or South America (combined) relocated to Spain, and the largest numbers of people moving from North America, Asia and Oceania moved to the United Kingdom.

Capital regions tended to record very high degrees of residential mobility in 2011 …

Turning attention to regional statistics, almost one third (30.7 %) of the population living in the Slovak capital region of Bratislavský kraj changed their residence during the 12-month period prior to the census. There were seven additional Slovak regions where upwards of one in five of the population moved home, and they were joined by two regions from the United Kingdom (Inner London - West and Nottingham).

An additional 17 of the 1 315 NUTS level 3 regions saw 15-20 % of their residents move in the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census: the vast majority of these (15 of the 17) were cities in the United Kingdom, while the other two were the Belgian and Danish capital regions of Arr. De Bruxelles-Capitale/Arr. Van Brussel-Hoofdstad and Byen København; there were also two regions in Norway where the share of residents moving home as a share of the total resident population was within the range of 15-20 %, the capital region of Oslo and Nord-Trøndelag.

… and were particularly attractive to those residents arriving from abroad

Almost one fifth (19.3 %) of the population of Bratislavský kraj moved within the same region during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census, the highest share among any of the 1 315 NUTS level 3 regions for which data are available. Bratislavský kraj also recorded the highest degree of residential mobility among those moving from another region in the same country (9.7 % of the total population). However, the highest share of new residents arriving from abroad was recorded in Inner London - West (4.6 % of the population). A more detailed analysis of the 50.5 thousand new residents who moved from abroad to Inner London - West during the 12-month period prior to the census reveals that more than half (53.3 %) were born outside the EU, while approximately one third (32.8 %) were born in another EU Member State, and 13.8 % were born in the United Kingdom (return migrants).

These patterns observed in the British capital were synonymous with those observed in many of the other EU Member States, insofar as the highest shares of residential mobility for those moving from abroad were recorded in the capital regions of Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland, Latvia, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Slovakia and Sweden.

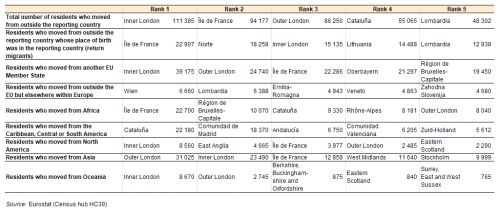

In 2011, London, Paris, Cataluña and Lombardia were the most popular regions in the EU for new residents arriving from abroad

Table 3 provides similar information to that shown in Table 2, but focuses on population and housing census data for NUTS level 2 regions. It shows the five most popular destinations for new residents moving from abroad in 2011 were all large metropolitan regions, they included: Inner London (111.4 thousand people), the Île de France (94.2 thousand), Outer London (86.3 thousand), Cataluña (55.1 thousand) and Lombardia (48.3 thousand).

The destinations commonly chosen by migrants moving from abroad were often quite concentrated, perhaps reflecting the desire to move close to fellow citizens when arriving in a new country. For example, of the 19.6 thousand new residents who arrived in the United Kingdom from Oceania, almost 60 % moved to Inner or Outer London. In a similar vein, nearly half of the non-EU Europeans who moved to Austria were resident in Wien, while almost half of those who moved to Spain from the Caribbean, Central or South America were resident in either Cataluña or the Comunidad de Madrid, and almost one third of all Africans who moved to France were resident in Paris.

It is also interesting to analyse the distribution of return migrants, in other words people born in the reporting country, but moving back from another country. In Lithuania (a single region at this level of detail), this group accounted for 90.0 % of those moving from abroad. This may, at least in part, be explained by relatively high numbers of Lithuanians leaving home in search of work following accession to the EU in 2004, a pattern that was reinforced by a rapid contraction in economic activity in 2008 as a result of the global financial and economic crisis, while the subsequent recovery in the Lithuanian economy may have led some migrants to consider returning home.

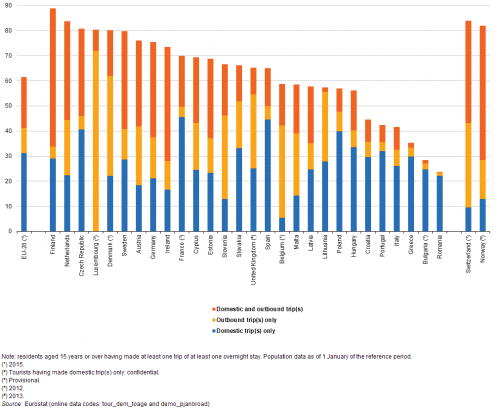

European tourists on the move

This article closes with an alternative perspective of mobility, namely, tourism opportunities that are open to Europeans for discovering other regions within their own country, neighbouring European countries, or cultures further afield on other continents.

Within the EU, the Schengen area has enhanced the freedom of movement of individuals since 1995, allowing people to cross internal borders without being subjected to border controls and checks when travelling between most EU Member States. Today, the Schengen area encompasses all but six of the EU Member States and also includes Iceland, Liechtenstein Norway and Switzerland; Ireland and the United Kingdom have opt-outs, while the membership of Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Romania is currently under preparation.

Based on Eurostat’s tourism statistics, Figure 11 shows the proportion of EU residents (aged 15 years and over) having made at least one trip with an overnight stay for personal reasons; the data are analysed by the tourist’s destination. In 2015, some 61.4 % of the EU-28’s residents enjoyed some form of holiday for personal reasons. Just over half of them (50.6 %) made a domestic trip (or trips), while around one sixth (16.3 %) of the adult population took a holiday abroad in a foreign destination and 33.0 % made a domestic trip(s) and took a holiday(s) abroad.

Data for 2016 are available for most of the EU Member States (data for Belgium, Bulgaria and Denmark refer to 2015; data for the United Kingdom refer to 2012): in Finland, as many as 88.9 % of the population aged 15 years and over had at least one night of holiday, while more than four fifths of the adult populations of the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Luxembourg and Denmark took part in tourism. At the other end of the scale, just over one third (35.2 %) of the Greek population had at least one overnight stay in 2016, a share that fell to around one quarter of the adult population in Bulgaria (28.4 %; 2015 data) and Romania (23.7 %).

Tourists from Luxembourg, Denmark and the Netherlands were most inclined to take foreign holidays in 2016, which may be attributed — at least in part — to their relatively small land area, their location, and the comparative wealth of their citizens. The most extreme example was in Luxembourg, where almost three quarters (72.0 %) of the adult population went exclusively on holiday abroad. In neighbouring Belgium only 5.4 % of the adult population went exclusively on holiday in their own country. By contrast, in Romania (1.5 %), Bulgaria (3.7 %; 2015 data) and Greece (5.4 %), fewer than 1 in 10 adults went on holiday abroad, this share rising to 10-20 % in Portugal, Croatia, Italy and Poland.

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (tour_dem_toage) and (demo_pjanbroad)

Source data for tables and graphs

Direct access to

- All articles from Archive:People in the EU: who are we and how do we live?

- Population and housing census data — the Census hub

- Income and living conditions (ilc)

- Population (demo_pop)

- Migration and citizenship data, see:

- Immigration (migr_immi)

- Emigration (migr_emi)

- Acquisition and loss of citizenship (migr_acqn)

- EU legislation on the 2011 Population and Housing Censuses - Explanatory Notes

- Legislation relevant for the population and housing census

- Target variables and common guidelines for EU-SILC

- Legislation relevant for income and living conditions statistics

- Demographic statistics: a review of definitions and methods of collection in 44 European countries

- Legislation relevant for population statistics