SDG 11 - Sustainable cities and communities

Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable

Data extracted in April 2024.

Planned article update: June 2025.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’. This report is the eighth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 11 aims to renew and plan cities and other human settlements in a way that offers opportunities for all, with access to basic services, energy, housing, transport and green public spaces, while reducing resource use and environmental impact.

Full article

Sustainable cities and communities in the EU: overview and key trends

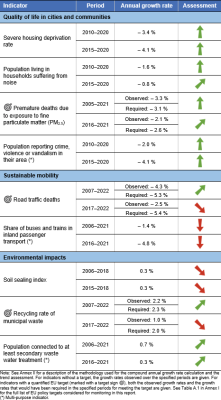

Around 332 million people or almost three-quarters of the EU population live in urban areas — cities, towns and suburbs — with almost 39 % residing in cities alone [1]. With the share of Europe’s urban population projected to rise to just over 80 % by 2050 [2], sustainable cities, towns and suburbs are therefore essential for citizens’ well-being and quality of life. Monitoring SDG 11 in an EU context means looking at developments in the quality of life in cities and communities, sustainable mobility and adverse environmental impacts. Overall, the EU has made only modest progress towards SDG 11 over the past five-year period assessed. While there has been quite strong progress in increasing the quality of life in cities and communities, trends in the area of sustainable mobility are less clear-cut and are moreover impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The picture is similarly diverse when it comes to adverse environmental impacts, with both sustainable and unsustainable trends visible.

Quality of life in cities and communities

While European cities and communities provide opportunities for employment, and economic and cultural activity, many inhabitants still face considerable social challenges and inequalities. Problems affecting the quality of housing and the wider residential area, such as noise disturbance, crime and vandalism, are some of the most visible challenges that cities and communities can face and that impact quality of life.

Quality of housing in the EU has improved since 2010

Safe and adequate homes are a foundation for living an independent, healthy and fulfilling life. Poor housing conditions, on the other hand, are associated with lower life chances, health inequalities, increased risks of poverty and environmental hazards.

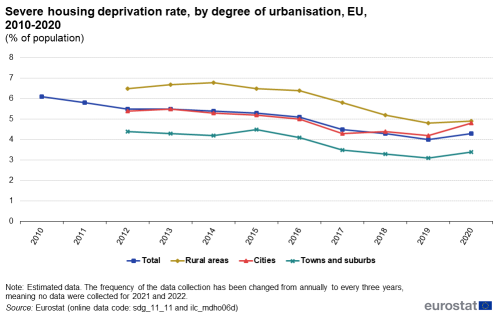

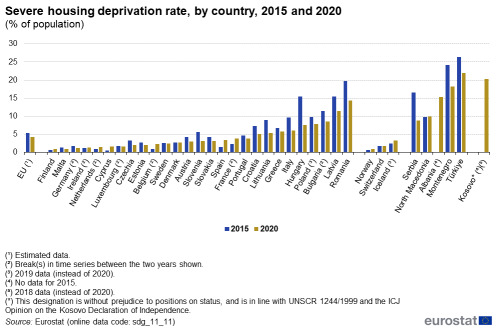

The severe housing deprivation rate refers to the share of the population living in an overcrowded household while also experiencing types of housing deprivation such as a leaking roof, damp walls, floors or foundations; rot in window frames or floors; lacking sanitary facilities; or a dwelling that is considered too dark. Between 2010 and 2020, the share of EU residents who lived in such conditions fell by 1.8 percentage points, which indicates a significant improvement in the perceived quality of the EU’s housing stock.

Europeans perceive their residential areas as quieter and safer

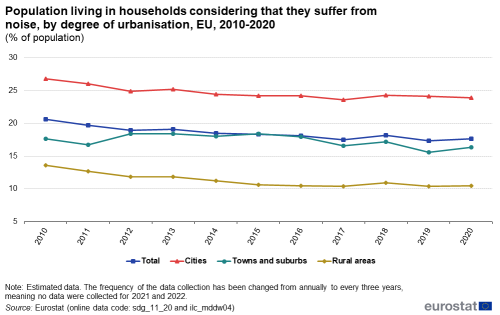

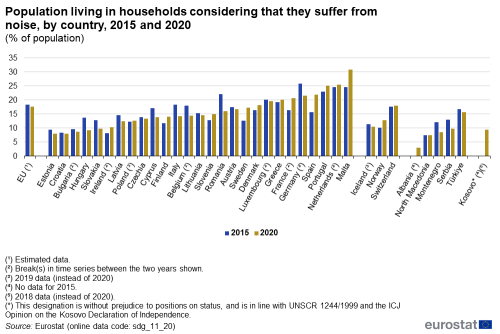

Noise disturbance can cause annoyance, stress, sleep deprivation, poor mental health and well-being, as well as harm to the cardiovascular and metabolic system [3]. Likewise, crime and vandalism can also reduce quality of life and housing satisfaction in a residential area. In 2020, 17.6 % of the EU population (close to 79 million people) said their household suffered from noise disturbance, compared with 20.6 % in 2010. Crime, violence and vandalism in the neighbourhood were perceived by 10.7 % of the EU population in 2020, compared with 13.1 % in 2010.

The EU’s zero pollution action plan aims to reduce the share of people chronically disturbed by transport noise by 30 % by 2030 compared with 2017. At 55 decibels (dB) noise levels can start to have critical effects, ranging from severe annoyance and sleep disturbance to hearing impairment [4]. The more recent WHO guidelines for Europe are even more stringent, recommending that the noise level from road traffic should be below 53 dB during the day and below 45 dB at night. Despite improvements in perceived exposure to noise, 95 million people in the EU were estimated to be exposed to road traffic noise at levels of 55 dB or higher on an annual average for day, evening and night in 2017. While railways and airports represent further significant sources of local noise pollution, their impact on the overall population is much lower. The number of people exposed to harmful noise levels has not decreased significantly since 2012 [5]. A recent outlook from the European Environment Agency (EEA) suggests that meeting the zero pollution action plan’s 30 % noise reduction target will be challenging, with the most optimistic scenario only estimating a 19 % reduction.

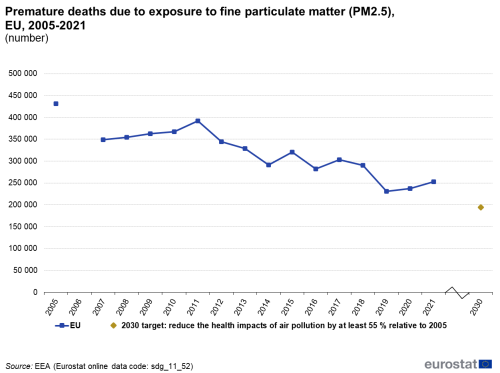

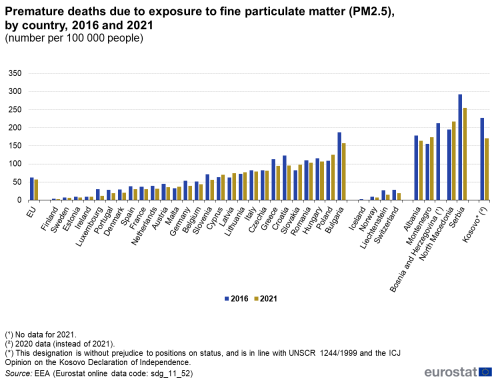

Exposure to fine particulate matter in the EU leads to premature deaths and lost years of life

Pollutants such as fine particulate matter (PM2.5) suspended in the air reduce people’s life expectancy, and can lead to or aggravate many chronic and acute respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [6]. Exposure to air pollution is of particular concern in cities because the concentration of economic activities and high population densities mean there are many potential emission sources and a large number of people being affected by air pollutants.

According to data from the European Environment Agency (EEA), in 2021 four EU Member States (Italy, Czechia, Croatia and Poland) registered annual mean PM2.5 concentrations above the EU limit value of 25 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3) [7], which has been attributed primarily to increased burning of solid fuels for domestic heating and industrial purposes. However, when considering the more stringent 2021 WHO air quality guideline of 5 μg/m3, all EU Member States reported concentration levels that exceeded the limit. In 2021, most of the EU’s population was exposed to key air pollutants, especially in urban areas with almost all EU city dwellers (97 %) being exposed to PM2.5 concentrations above the WHO guideline.

In the EU, long-term exposure to fine particulate matter was responsible for around 253 305 premature deaths in 2021. The number of premature deaths in the EU increased by 6.6 % between 2020 and 2021. Nevertheless, the 2021 level represents a 41 % reduction since 2005, meaning the EU appears to be on track to meet the zero pollution action plan target for 2030. This aims to reduce the number of premature deaths due to fine particulate matter exposure by more than 55 % compared with 2005 [8]. According to EEA estimates, if the long-term trend can be sustained over the next few years, the EU could achieve a 68 % decline in this number, thereby overachieving the EU’s 2030 target.

City dwellers experience more noise pollution and crime

Statistics on the degree of urbanization provide an analytical and descriptive lens through which to view urban and rural communities. Based on the share of the local population living in urban clusters and urban centres, Eurostat differentiates between three types of area: ‘cities’, ‘towns and suburbs’ and ‘rural areas’ [9].

The severe housing deprivation rate in the EU in 2020 was higher in rural areas (4.9 %) than in cities (4.8 %) and in towns and suburbs (3.4 %) [10]. The perceived level of noise pollution varies greatly depending on the degree of urbanisation. In 2020, people living in EU cities were more likely to report noise from neighbours or from the street (23.9 %) compared with those living in towns and suburbs (16.3 %) or in rural areas (10.5 %) [11]. Similarly, the perceived occurrence of crime and vandalism in cities (16.3 %) was almost three times higher than in rural areas (5.8 %) and above the level observed in towns and suburbs (8.4 %) in 2020 [12].

Access to green spaces makes urban residents more satisfied with their city

Green spaces in cities have a great potential to boost human health and well-being, and play a crucial role for children, the elderly and those with lower incomes, who may otherwise have limited access to nature. Universal accessibility to these green spaces that are safe, inclusive and open is thus essential. According to the survey on quality of life in European cities in 2023, around 76 % of European urban residents were satisfied with green spaces available within their city. This satisfaction rate was lower for those living in capital cities (73 %) compared with non-capital cities (78 %). Overall, Geneva, Malmö, Oslo and Munich received the highest scores from their residents, with more than 90 % of the people surveyed in these cities stating satisfaction with their green spaces. Four of the top 10 cities with the highest satisfaction rates in Europe lie in the Scandinavian region. Among the Member States, southern countries showed lower than average satisfaction with green spaces, with rates below 60 %. Overall, urban residents in Europe with greater access to green spaces tend to be more satisfied with the cities they live in. This was especially noted for retired residents, where access to green urban areas within 400 metres of walking was associated with lower levels of loneliness felt.

Sustainable mobility

A functioning transport system is necessary for people to reach their places of work, education, services and social activities, all of which affect quality of life and equal opportunities for everyone. In addition to availability, the type, quality and safety of transport systems are also crucial when designing sustainable and inclusive cities and communities.

Use of public transport modes remains below pre-pandemic levels

The EU aims to improve citizens’ quality of life and to strengthen the economy by promoting sustainable urban mobility and greater use of clean and energy-efficient vehicles, together with reducing the demand for individual car transport. Public transport networks help to relieve traffic jams, reduce harmful pollution and offer more affordable and sustainable ways to commute to work, access services and travel for leisure.

Since 2000, the share of buses and trains in inland passenger transport has stagnated well below 20 %, accounting for only 13.7 % of passenger-kilometres (pkm) in 2021. The onset of the pandemic in 2020 drastically hit this sector, with its share falling by 4.7 percentage points compared with 2019, to 12.9 %. The precautionary measures put in place, including domestic and international travel restrictions, quarantine restrictions, introduction of remote-working policies and changing mobility habits led to a reduction in the use of public transport [13] and passengers’ perceptions about safety and comfort. The slight increase in the share of buses and trains in inland passenger transport in 2021 by 0.8 percentage points relative to 2020 might signify a potential recovery from the pandemic. Nonetheless, the decline in the shares of public modes of mobility remains significant compared with pre-pandemic levels, showing a reduction by 3.3 percentage points since 2006 and by 3.8 percentage points since 2016.

Cars continue to remain the dominant form of passenger mobility [14] in the EU, accounting for 86.3 % of passenger-kilometres travelled in the EU in 2021. This represents a 3.9 percentage point increase compared with the pre-pandemic values from 2019 [15]. According to an EU-wide survey on passenger mobility carried out in 2021, 64 % of the respondents reported that their travel behaviour was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This study also revealed that, after cars, active mobility (walking and cycling) was the second most used mode of transport. A study from 2023 on the effects of the pandemic on connectivity and competition in transport indicates that the shift away from public transport to private cars and to active mobility persisted in 2022.

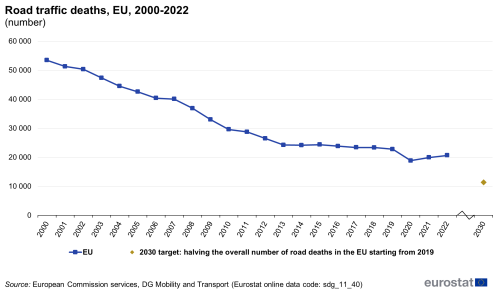

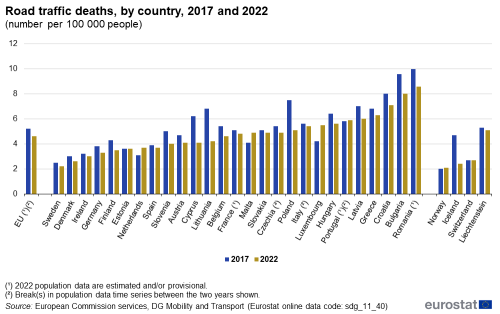

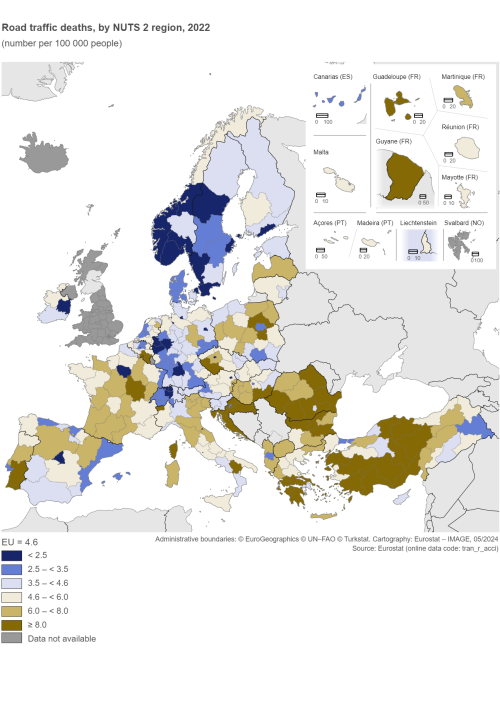

Deaths from road crashes have fallen, but greater progress will be necessary to meet the 2030 target

Road traffic injuries are a public health issue and have a huge economic cost. About 120 000 people are estimated to be seriously injured in road accidents in the EU each year [16]. In 2022, about 57 people a day lost their lives on EU roads. This corresponds to slightly more than 20 600 people for the entire year — a loss equivalent to the size of a medium town. Nevertheless, the EU has made considerable progress in this respect compared with 2007, when road deaths amounted to about 40 000. In recent years, the figures have experienced some fluctuations, in part explained by significant changes in traffic volumes as a result of to the COVID-19 pandemic. After an unprecedented fall in road traffic deaths of 17.2 % between 2019 and 2020, the number has been on the rise since, increasing by 9.7 % between 2020 and 2022. The most recent figures, based on preliminary figures for 2023, show the number of road deaths in the EU have seen a small decrease of 1 % since 2022. Consequently, the EU as a whole is not on track to meet its 2030 target of halving the total death toll on EU roads compared with 2019.

The highest share of road-traffic fatalities in 2022 was recorded on non-motorway roads outside urban areas (52 %), followed by roads inside urban areas (38 %) and motorways (9 %). Almost 70 % of fatalities in urban areas involve vulnerable road users such as pedestrians, motorcyclists and cyclists [17]. Data by mode of transport show that over the period 2019 to 2022, road fatalities have decreased for all modes except heavy goods vehicles, which saw a 7 % increase in fatal road accidents [18]. According to the thematic report on alcohol and drugs by European Road Safety Observatory, around 25 % of all road deaths in the EU are alcohol related, and it is estimated that 1.5 % to 2 % of the kilometres driven in the EU are done by a driver with illegal blood alcohol content.

Environmental impacts

While cities, towns and suburbs are a focal point for social and economic activity, if not managed sustainably, they risk causing considerable environmental damage. At the same time, large and densely populated cities provide opportunities for effective environmental action, indicating that urbanisation is not necessarily a threat but can act as a transformative force for more sustainable societies [19]. EU progress in reducing the environmental impacts of cities and communities is monitored by three indicators on the management of municipal waste, waste water treatment and artificial land cover.

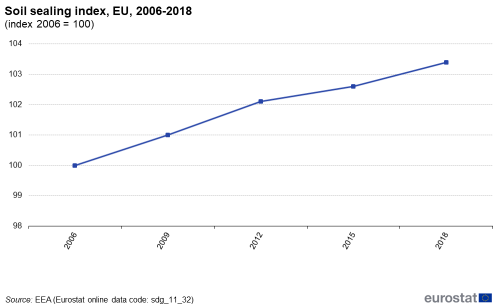

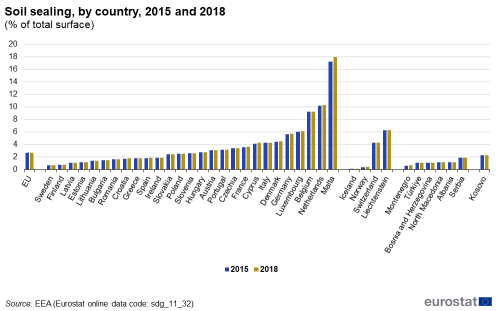

Soil sealing is increasing slowly but constantly in the EU

Offering numerous cultural, educational and job opportunities, an urban lifestyle is attractive to many people. However, growth in the urban population has also come with increased land take. Land take is described as the process of transforming agricultural, forest and other semi-natural and natural areas into artificial areas. Between 2012 and 2018, the net land take in cities and their commuting zones, also known as functional urban areas, amounted to 450 square kilometres (km2) annually. Additionally, most of the net land take (about 78 %) happened in commuting areas [20].

Soil sealing is the most intense form of land take and is essentially an irreversible process. It destroys or covers soils with layers of partly or completely impermeable artificial material such as asphalt and concrete [21]. Increases in the extent of sealed land can be used to estimate land-use change for human use or intensification. The area of sealed soil in the EU has increased in all Member States since 2006. Between 2006 and 2018, the total EU area covered with impervious materials grew by 3 605 km2 or 3.4 %. In 2018, the area of sealed soil surface reached 2.7 % in the EU. Across Member States, the share of area covered with impervious materials ranged from below 1 % in Sweden and Finland to around 10 % in Belgium and the Netherlands up to 18 % in Malta.

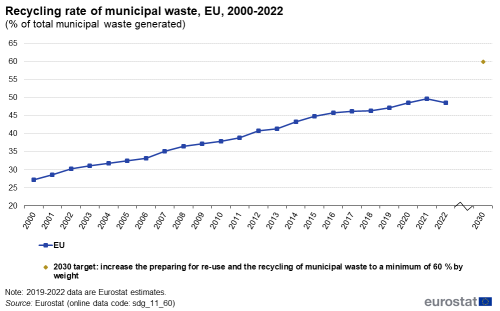

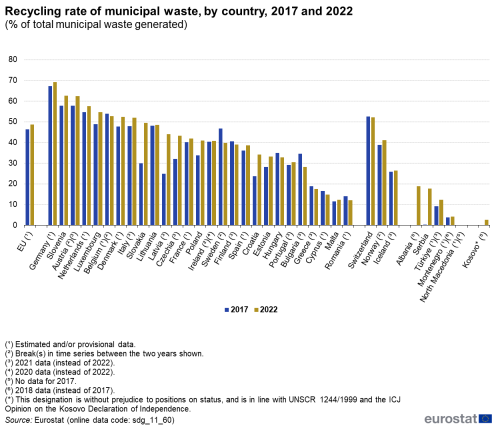

The EU might miss its target for municipal waste recycling as progress slows

The ‘waste hierarchy’ is the overarching logic that guides EU waste policy. It prioritises waste prevention, followed by preparing for reuse, recycling, other recovery and finally disposal, including landfilling, as the last resort. Waste management activities promote recycling, which reduces the amount of waste going to landfills and leads to higher resource efficiency. Although municipal waste accounts for less than 10 % of the weight of total waste generated in the EU [22], it is highly visible and closely linked to consumption patterns. Sustainable management of this waste stream reduces the adverse environmental impact of cities and communities, which is why the EU has set a target to recycle or prepare for reuse at least 60 % of its municipal waste by 2030 [23].

In 2022, the EU residents generated 229 482 thousand tonnes of municipal waste, corresponding to 513 kilograms (kg) of waste per capita per year [24]. Since 2017, the annual amount of waste generated per capita increased by 14 kg, which represents an increase of about 3 % between 2017 and 2022. Although the EU has not reduced its municipal waste generation, it has clearly shifted to more recycling. Since 2000, the recycling rate of municipal waste — covering both recycling and preparing for re-use — has increased from 27.3 % to 48.6 % in 2022. However, this trend has slowed in the short run, with the recycling rate dropping by 1.2 percentage points between 2021 and 2022. Over the short-term period from 2017 to 2022, the share of recycled municipal waste only increased by 2.3 percentage points. Stronger efforts are therefore needed to put the EU back on track to meet its 2030 recycling targets.

Connection rates to waste water treatment have been increasing

Urban areas also place significant pressure on the water environment through waste water from households and industry that contains organic matter, nutrients and hazardous substances. The share of the EU population connected to at least secondary waste water treatment plants, which decompose most of the organic material and retain some of the nutrients, has been steadily growing since 2000 and reached 80.9 % in 2021. In seven Member States, more than 90 % of the population were connected to such services according to most recent data (which refer to 2017, 2019, 2020 or 2021, depending on the country). However, it may not be suitable to connect 100 % of the population to a sewerage collection system, either because it would produce no environmental benefit or would be too costly (see article on SDG 6 ‘Clean water and sanitation’).

Main indicators

Severe housing deprivation rate

The severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the percentage of the population living in a dwelling which is considered to be overcrowded, while also exhibiting at least one of the following housing deprivation measures: i) a leaking roof, ii) no bath/shower and no indoor toilet, and iii) considered too dark. The data stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Source: Eurostat (online data codes: (sdg_11_11) and (ilc_mdho06d))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_11_11)

Population living in households suffering from noise

This indicator measures the share of the population who declare they are affected either by noise from neighbours or from the street. Because the assessment of noise pollution is subjective, it should be noted that the indicator accounts for both the levels of noise pollution as well as people’s standards of what level they consider to be acceptable. Therefore, an increase in the value of the indicator may not necessarily indicate a similar increase in noise pollution levels; it may also indicate a decrease in the levels that European citizens are willing to tolerate and vice versa. In fact, there is empirical evidence that perceived environmental quality by individuals is not always consistent with the actual environmental quality assessed using ‘objective’ indicators, particularly for noise. The data stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (online data codes: (sdg_11_20) and (ilc_mddw04))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_11_20)

Premature deaths due to exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5)

The indicator measures the number of premature deaths due to exposure to particulate matter. Fine particulates (PM2.5) are particulates whose diameter is less than 2.5 micrometres, meaning they can be carried deep into the lungs where they can cause inflammation and exacerbate the condition of people already suffering from heart and lung diseases. Premature deaths refer to those deaths that occur before the expected age of death. This expected age is typically defined by accounting for the life expectancy in the country, stratified by sex and age. The data stem from the European Environment Agency.

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_11_52)

Source: EEA, Eurostat (sdg_11_52)

Road traffic deaths

This indicator measures the number of fatalities caused by road crashes, including drivers and passengers of motorised vehicles and pedal cycles, as well as pedestrians. Persons dying on road crashes up to 30 days after the occurrence of the crash are counted as fatalities. The data come from the CARE database managed by DG Mobility and Transport (DG MOVE).

Source: European Commission services, DG Mobility and Transport, Eurostat (sdg_11_40)

Source: European Commission services, DG Mobility and Transport, Eurostat (sdg_11_40)

Source: Eurostat (tran_r_acci)

Soil sealing index

This indicator estimates the increase in sealed soil surfaces with impervious materials due to development and construction (such as buildings, constructions and laying of completely or partially impermeable artificial material, such as asphalt, metal, glass, plastic or concrete). This provides an indication of the rate of soil sealing, which occurs when there is a change in land use towards artificial and urban land use. The indicator builds on data from the Imperviousness High Resolution Layer (a product of the Copernicus Land Monitoring Service).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_11_32)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_11_32)

Recycling rate of municipal waste

This indicator measures the tonnage recycled or prepared for re-use from municipal waste divided by the total municipal waste arising. Recycling includes material recycling, composting and anaerobic digestion. Municipal waste consists mostly of waste generated by households but may also include similar wastes generated by small businesses and public institutions and collected by the municipality. This latter part of municipal waste may vary from municipality to municipality and from country to country, depending on the local waste management system. For areas not covered by a municipal waste collection scheme the amount of waste generated is estimated.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_11_60)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_11_60)

Direct access to

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’.

Further reading on sustainable cities and communities

- EEA (2022), Air Quality in Europe 2022, EEA Report no. 05/2022, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- Eurostat (2023), Eurostat regional yearbook 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- EEA (2024), Urban adaptation in Europe: what works? Implementing climate action in European cities, EEA Report 14/2023

- Joint Research Centre (2021), Atlas of the Human Planet 2020, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- The Housing Europe (2023), The State of Housing in Europe 2023, Housing Europe, the European Federation for Public, Cooperative and Social Housing, Brussels.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2018), The World’s Cities in 2018 — Data Booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/417).

- UN-Habitat (2022), World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the future of cities.

- WHO (2023), Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018), Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region.

Further data sources on sustainable cities and communities

Notes

- ↑ 2020 data. Source: Eurostat (online data codes: (ilc_lvho01) and (demo_gind)).

- ↑ Eurostat (2016), Urban Europe: Statistics on cities, towns and suburbs, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 9.

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2019), Population exposure to environmental noise.

- ↑ Berglund, B., Lindvall, T., Schwela, D.H. (1999), Guidelines for Community Noise, World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva.

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2023), Noise pollution and health.

- ↑ WHO (2021), WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide, World Health Organization; and European Environment Agency (2023), Harm to human health from air pollution in Europe: burden of disease 2023, Briefing no. 23/2023.

- ↑ For PM2.5, the Ambient Air Quality Directive 2008/50/EC introduced a target value to be attained by 2010, which became a limit value starting in 2015. For more information on EU air quality standards see: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/air/quality/standards.htm

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2023), Monitoring report on progress towards the 8th EAP objectives 2023 edition, EEA Report 11/2023; European Environment Agency (2023), 8th Environment Action Programme: Premature deaths due to exposure to fine particular matter in Europe; European Commission (2022), Zero Pollution Monitoring and Outlook Report.

- ↑ Degree of urbanisation classifies local administrative units as ‘cities’, ‘towns and suburbs’ or ‘rural areas’. In ‘cities’ at least 50 % of the population lives in an urban centre. If less than 50 % lives in an urban centre but more than 50 % of the population lives in an urban cluster it is classified as ‘towns and suburbs’, and if more than 50 % of the population lives outside an urban cluster it is classified as a ‘rural area’. An urban centre is a cluster of contiguous grid cells of 1 square kilometre (km2) with a density of at least 1 500 inhabitants per km2 and a minimum population of 50 000 people. An urban cluster is a cluster of contiguous grid cells of 1 km2 with a density of at least 300 inhabitants per km2 and a minimum population of 5 000 people.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_mdho06D)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_mddw04)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_mddw06)).

- ↑ European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union; Lozzi, G., Ramos, C., Cré, I. (2022), Relaunching transport and tourism in the EU after COVID-19; Part VI, Public transport, European Parliament.

- ↑ Tram and metro systems, as well as active modes (walking, cycling), are not included because the data collection methodology for these means of transport is not sufficiently harmonised between Member States.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (tran_hv_psmod)).

- ↑ European Commission (2020), Road safety: Europe’s roads are getting safer but progress remains too slow.

- ↑ European Commission (2024), 2023 figures show stalling progress in reducing road fatalities in too many countries.

- ↑ European Commission (2024), Annual statistical report on road safety in the EU, 2024. European Road Safety Observatory, Brussels, p. 14.

- ↑ UN-Habitat (2016), Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures, World Cities report 2016, pp. 85–100.

- ↑ European Environment Agency (2023), 8th Environment Action Programme. Land Take: net land take in cities and commuting zones in Europe.

- ↑ Prokop G, Jobstmann H, Schonbauer A (2011), Report on best practices for limiting soil sealing and mitigating its effects, Brussels.

- ↑ Eurostat (2024), Statistics explained: Municipal waste statistics.

- ↑ European Commission (2018), Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste (Text with EEA relevance).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (env_wasmun))