Data extracted in May 2025.

Planned article update: June 2026.

Highlights

Participation rate in education and training by sex, 2022

This article provides an overview of adult learning statistics in the European Union (EU). It draws on data collected through the adult education survey (AES) and supplemented by data from the EU labour force survey (EU-LFS). It focuses on the key indicator of ‘participation in formal and non-formal education and training in the last 12 months’ and explains the differences between the data available from the 2 data sources. It also presents EU-LFS data on recent participation in education and training (i.e. in the last 4 weeks) and the policy indicator entitled ‘share of unemployed adults with a recent learning experience’, which is used as part of the European Skills Agenda. Finally, it presents some AES data on informal learning.

Adult learning (also referred to as lifelong learning) is defined as the participation in education and training for adults aged 25-64. The importance of adult learning is reflected in EU-level targets, namely that:

- by 2025, at least 47% of adults aged 25-64 should have participated in learning during the last 12 months (European Education Area); and

- by 2030, at least 60% of all adults should be participating in training every year (European pillar of social rights).

This article is part of a series of statistical articles that make up the online publication Education and training in the EU - facts and figures.

For more information on this subject, see the following 3 articles:

- Adult learning - participants

- Adult learning statistics - characteristics of education and training

- Adult_learning - reasons for not participating.

Participation in education and training in the last 12 months

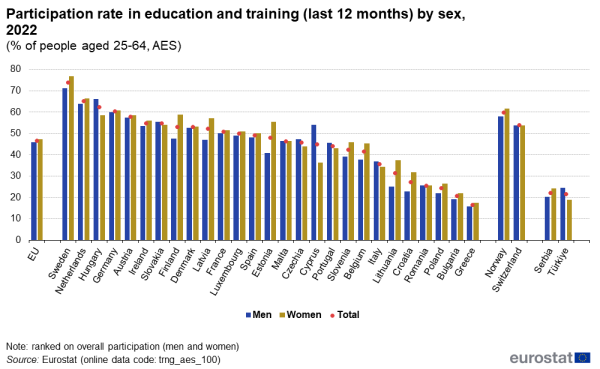

In 2022, according to the adult education survey (AES), the proportion of adults aged 25 to 64 in the EU who had participated in education or training during the previous 12 months was 46.6% (see Figure 1). Sweden and the Netherlands reported the highest participation rates (over 65%), while Poland, Bulgaria and Greece had the lowest ones (below 25%).

(% of people aged 25-64, AES)

Source: Eurostat (trng_aes_100)

Data refer to participation in formal or non-formal education and training. In order to give an appropriate measure of participation in adult learning, the reference period for the indicator is the last 12 months, i.e. the indicator reflects participation in training activities during a whole year. The main indicator on adult participation in learning refers to the 25-64 age bracket.

The share of the population who participated in adult learning was slightly higher among women (47.2% in 2022) in the EU than among men (46.0%). In 2022, women recorded higher participation rates than men in 21 EU countries. The largest differences between men and women were in Estonia, Lithuania and Finland, where the participation rate for women was more than 10 percentage points (pp) higher than for men. On the other hand, in Cyprus, the participation rate for men was 17.7 pp higher than that for women.

For detailed information on the characteristics of participants, see adult learning - participants.

Participation in education and training during the last 12 months – differences between the data available from 2 sources

Until 2021, the adult education survey (AES) was the only source of data for adult participation in learning in the last 12 months. However, as the AES only takes place every six years, variables were introduced into the EU labour force survey (EU-LFS) to collect data every two years (starting in 2022). The aim of this was to enable more frequent analysis and monitoring of initiatives related to employment and skills policies, particularly in the context the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) and the European Education Area (EEA).

Comparing the 2022 results from AES and EU-LFS revealed noticeable differences. The following reasons for such differences emerged from in-depth analyses of data and metadata (for details see Information note):

- survey purpose – education survey vs labour force survey

- coverage of education and training – non-formal education and training excludes the category ‘guided on-the-job training’ in the EU-LFS

- variables for non-formal education and training – the variables for non-formal education and training (NFE) are more detailed in the AES than in the EU-LFS

- national questionnaires – the number and wording of questions can differ as well as their position in the questionnaire

- use of proxies – proxy answers are more common in the EU-LFS than in the AES

- interviewer training – naturally more focused on education in AES than in the EU-LFS

- response bias due to social desirability – AES might somewhat over-estimate participation in education and training because of socially desirable responding

- data collection period – EU-LFS is a continuous quarterly survey, while the AES data collection takes place every 6th year with a fixed timeslot for fieldwork

- methodological differences between the surveys – such as sample size, sampling unit, data collection mode (in particular personal or via internet), response rates, etc.

These reasons for the differences between AES and EU-LFS results have to be kept in mind when analysing the data.

Eurostat considers that levels of adult learning are, in general, more appropriately measured with the AES, while the EU-LFS could provide further insights into trends and in-depth cross-sectional analyses that would not be possible with AES (mainly owing to the smaller sample size).

Participation rates in education and training from the EU-LFS differ …

Since 2022, the EU-LFS has provided data on participation in education and training in the last 12 months. However, both at the EU level and for many individual countries, the results differ from the AES results. Reasons for the differences are described in the box above.

In 2024, according to the EU labour force survey (EU-LFS) the proportion of adults aged 25 to 64 in the EU who participated in education or training during the previous 12 months was 28.1% (see Figure 2). Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Finland reported the highest participation rates (over 50%), while Bulgaria and Greece had the lowest (below 9%).

(% of people aged 25-64, EU-LFS)

Source: Eurostat (trng_lfs_17)

Participation rates by sex showed the same pattern as AES results: the share of the population who had participated in adult learning was slightly higher among women (29.0% in 2024) in the EU than among men (27.3%). Women recorded higher participation rates than men in 19 EU countries. The largest differences between men and women were in Estonia, Sweden, Finland, Latvia and Denmark, where the participation rate for women was more than 10 pp higher than for men. On the other hand, in Slovakia, the participation rate for men was 4.4 pp higher than that for women.

… but the structure of participants is about the same in AES and EU-LFS

While the levels of adult learning reported by AES and EU-LFS differed, looking at the main characteristics of adult learners show similar patterns for the results from the 2 surveys at the EU level (see Figures 3 and 4).

(%, AES)

Source: Eurostat (trng_aes_101), (trng_aes_102) and (trng_aes_103)

(%, EU-LFS)

Source: Eurostat (trng_lfs_17), (trng_lfs_18) and (trng_lfs_19)

The following can be observed:

- Firstly, younger people were more likely to participate in education and training than older people.

- Secondly, employed people are far more likely to participate in education and training than the unemployed, while the least likely to participate were those outside the labour force.

- Thirdly, when it comes to educational attainment, people with a tertiary education were most likely to participate in adult learning. Following at some distance are those with a medium level of education with a qualification from a general programme; some of these people may pursue further studies to attain either a vocational qualification, or a tertiary qualification. The least likely to participate were those with a low level of education.

These patterns are repeated at a national level in most countries.

Net increase in recent participation in formal or non-formal education and training

Over the last 10 years there has been a net increase in recent participation in formal or non-formal education and training. Time series on recent participation in education and training, i.e. in formal or non-formal learning activities in the last 4 weeks, are available from the EU-LFS. In the EU, participation rates first rose moderately, from 10.1% in 2014 to 10.8% in 2019. Then, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, participation rates fell sharply to 9.1%. Since 2021, participation rates have shown somewhat stronger growth than before the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, it should be noted that there is a break in the EU-LFS time series in 2021 because of a change in the legislation underpinning the survey. At least a part of the observed growth can also be attributed to methodological improvements in national questionnaires, in particular as regards participation in non-formal education and training.

(% of people aged 25-64, EU-LFS)

Source: Eurostat (trng_lfse_01)

Participation rates for women and men have largely developed in the same way over the last 10 years, with consistently higher participation rates for women than for men. In 2014, 10.9% of women participated in adult learning, compared with 9.3% of men, while in 2024, 14.5% of women and 12.1% of men participated. Over the last 10 years, the gender gap has widened from 1.6 pp in 2014 to 2.4 pp in 2024 in favour of women. Between 2014 and 2021 this gap was relatively stable at around 1.7 pp (with the exception of 2019 where it stood at 2.1 pp), but it has widened more since 2022.

In the EU, 15.3% of unemployed adults aged 25 to 64 had a recent learning experience in 2024

As part of the European Skills Agenda, the EU set an objective that, by 2025, the share of unemployed adults aged 25-64 with a recent learning experience should be at least 20%. In 2024, this share stood at 15.3%. Compared with 2014, when it was 9.4%, this share rose by 5.9 pp. This share ranged from 47.4% in Sweden to 3.3% in Hungary. 8 EU countries already met the target in 2024: Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, Luxembourg, Ireland, Estonia and Austria. However, shares below 10% were found in another 8 countries: Latvia, Poland, Lithuania, Czechia, Italy, Croatia, Greece and Hungary.

(% of unemployed people aged 25-64, EU-LFS)

Source: Eurostat (trng_lfs_02)

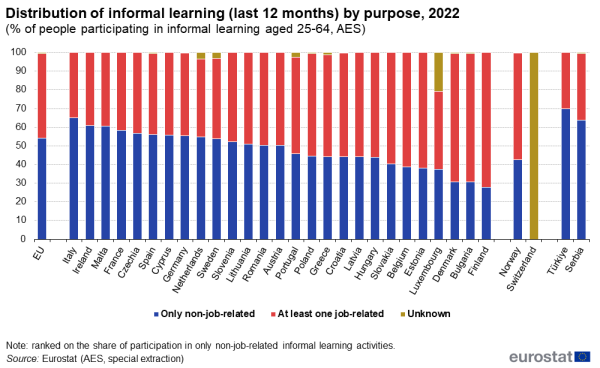

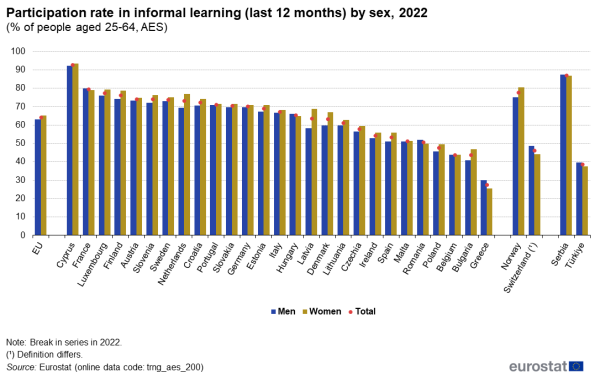

In 2022, 64.2% of adults participated in informal learning in the EU

In addition to information on participation in formal and non-formal education and training, the AES also collects information on informal learning. Typical forms of informal learning are, for example, taught learning through guided visits to museums or peer-to-peer coaching (i.e. organised but not institutionalised learning). Informal learning can also take place as non-taught learning, for example, as self-learning with electronic devices, such as watching a video on YouTube on how to repair a bike or self-learning with printed materials.

(% of people aged 25-64, AES)

Source: Eurostat (trng_aes_200)

In 2022, 64.2% of adults aged 25-64 in the EU reported participation in some informal learning in the 12 months preceding the interview (see Figure 7). Participation in informal learning ranged from below 30% in Greece to over 90% in Cyprus. The participation rate for women was 65.1% and 63.2% for men, resulting in a gender gap of 1.9 pp in favour of women in the EU. In most countries, more women than men reported informal learning activities. The largest gaps in favour of women (more than 7 pp) were found in Denmark, the Netherlands and Latvia. Participation in informal learning was higher for men only in France, Hungary, Romania and Greece. The largest gap in favour of men was in Greece, at 4.6 pp.

Figure 8 shows that in 13 EU countries, more than half of the informal learners indicated that all their informal learning activities were for leisure purposes (i.e. not job-related): Italy, Ireland, Malta, France, Czechia, Spain, Cyprus, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Slovenia, Lithuania and Romania. On the other hand, high shares – over 65% – of learners with at least one job-related informal learning activity were found in Denmark, Bulgaria and Finland.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Information on participation in education and training is available from 2 data sources – the adult education survey (AES) and the EU labour force survey (EU-LFS).

The AES covers adult participation in education and training (formal, non-formal and informal learning) and is one of the main data sources for EU lifelong learning statistics. Until 2016 AES, it covered adults of working age (25-64 years); since 2022 it has covered all adults aged 18-69 years.

AES – reference period and data collection period

The survey refers to all learning activities in which respondents may have participated during a 12-month period prior to the interview. The data collection for the 2022 AES took place in most countries between June 2022 and March 2023. For simplicity, data are referred to in this article as ‘2022’.

AES – waves

4 waves of the AES have been implemented so far: in 2007, 2011, 2016 and 2022. The first was a pilot exercise and was carried out on a voluntary basis, while since 2011, AES has been underpinned by a number of legal acts:

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 823/2010 for 2011 AES

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1175/2014 for 2016 AES

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 2021/861 from 2022 AES onwards.

Although the EU labour force survey (EU-LFS) is a survey about the working age population with a focus on labour market participation, it also collects variables on participation in education and training. Annual data on participation in education and training in the last 4 weeks have now been collected and made available for a long time. Since 2022, additional data on participation in education and training in the last 12 months have also been collected once every two years as part of the EU-LFS.

The EU-LFS is documented in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, and related concepts and definitions.

However, there are several methodological differences between these 2 sources, resulting in differences in the results. The differences between the 2 data sources are highlighted in the beginning of the article (see orange box) and detailed in an information note.

Classification

Levels of educational attainment

Common definitions for education systems have been agreed between the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), the OECD and Eurostat. UNESCO developed the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) to facilitate comparisons across Member States on the basis of uniform, internationally agreed definitions. In 2011, a revision to the ISCED was formally adopted, referred to as ISCED 2011. Prior to this, ISCED 1997 was used as the common standard for classifying education systems. For more information, see the article on the ISCED classification.

The levels of educational attainment are as follows:

- less than primary, primary or lower secondary level of education (ISCED 2011 levels 0-2; referred to as a 'low educational attainment level' or 'low level of education');

- upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED 2011 levels 3 and 4; referred to as a 'medium educational attainment level' or 'medium level of education'); at this level, information about whether the programme had general or vocational orientation is available;

- tertiary education (ISCED 2011 levels 5-8; referred to as a 'high educational attainment level' or 'high level of education').

Key concepts – formal and non-formal education and training, informal learning activities

The fundamental criterion for distinguishing learning activities from non-learning activities is that the learning activity must be intentional (and not by chance, i.e. ‘random learning’); in other words, it must be a deliberate search for knowledge, skills, competences or attitudes.

Broad categories of learning activities are defined in the International Standard Classification of Education 2011 (ISCED 2011). The Classification of learning activities (CLA) provides further details, in particular for non-formal learning activities.

- Formal education and training is defined as ‘education that is institutionalised, intentional and planned through public organisations and recognised private bodies and – in their totality – constitute the formal education system of a country. Formal education programmes are thus recognised as such by the relevant national education authorities or equivalent authorities, e.g. any other institution in cooperation with the national or sub-national education authorities. Formal education consists mostly of initial education. Vocational education, special needs education and some parts of adult education are often recognised as being part of the formal education system.’ (ISCED 2011)

- Non-formal education and training is defined as ‘education that is institutionalised, intentional and planned by an education provider. The defining characteristic of non-formal education is that it is an addition, alternative and/or complement to formal education within the process of the lifelong learning of individuals. It is often provided to guarantee the right of access to education for all. It caters to people of all ages but does not necessarily apply a continuous pathway-structure; it may be short in duration and/or low-intensity, and it is typically provided in the form of short courses, workshops or seminars. Non-formal education mostly leads to qualifications that are not recognised as formal or equivalent to formal qualifications by the relevant national or sub-national education authorities or to no qualifications at all. Non-formal education can cover programmes contributing to adult and youth literacy and education for out-of-school children, as well as programmes on life skills, work skills, and social or cultural development.’ (ISCED 2011)

The CLA further distinguishes the following broad categories of non-formal education:

- non-formal programmes

- courses (which are further categorised into classroom instruction, private lessons and combined theoretical-practical courses including workshops)

- guided on-the-job training.

In short, non-formal education and training covers institutionalised taught learning activities outside the formal education system.

Both AES and EU-LFS collect information on formal and non-formal education and training; and, in general, the 2 surveys adhere to the same concepts and definitions. However, there is one structural difference between the 2 surveys concerning the coverage of non-formal education and training: non-formal education and training excludes the category ‘guided on-the-job training’ in the EU-LFS, while it is included in the AES and in the data published from this survey in Eurostat’s online database.

- Informal learning is defined as ‘forms of learning that are intentional or deliberate, but are not institutionalised. It is consequently less organised and less structured than either formal or non-formal education. Informal learning may include learning activities that occur in the family, workplace, local community and daily life, on a self-directed, family-directed or socially-directed basis’. (ISCED 2011)

Information on informal learning activities is only collected in the AES.

Key concepts – labour status

In the AES, the self-perceived activity status is collected, i.e. the information on whether an individual is employed, unemployed or outside the labour force refers to the person’s own perception of their current main activity status. It does not apply criteria of a specific concept or definition, e.g. of labour market participation as defined by the International Labour Organization, as happens in the EU labour force survey.

Tables in this article use the following notation: ‘:’ not available, confidential or unreliable value.

Context

Upskilling – Reskilling

Adults with a low level of educational attainment and a lack of skills are more likely to earn lower than average wages and are more vulnerable to the precarious nature of the labour market. These individuals often suffer from a lack of basic skills that are increasingly considered essential for a modern-day economy: literacy, numeracy and technological skills (i.e. ‘digital literacy’). Indeed, in a world that is increasingly characterised by technological change and more precarious employment opportunities, it is becoming increasingly unlikely that people can rely on the skills they acquire at school/university to last them until the end of their working lives.

There are a variety of paths that people can potentially follow to gain additional education and training beyond the formal education and training system. Lifelong learning strategies imply investing in people and knowledge – promoting the acquisition of basic skills and providing opportunities for innovative, more flexible forms of learning. They aim to provide people of all ages with equal access to high-quality learning opportunities, and to a variety of learning experiences designed to increase employability, social inclusion and active citizenship.

For some people the decision to re-engage in education and training is a difficult one: it is therefore likely that a range of different approaches are required to offer participants flexible pathways. These may comprise formal, non-formal and informal learning, so that individuals engage in upskilling or reskilling to improve their employment opportunities and lives in general. Investment in adult skills has the potential to improve an individual’s quality of life by raising potential earnings, increase their job satisfaction and job opportunities, and promote their social mobility. From a policy perspective, adult education and training has the potential to help the EU to boost its competitiveness in globalised markets, develop a more highly skilled workforce to meet employers’ demands, keep an ageing workforce productive and move people out of welfare. Such developments are increasingly important in a global context, given the rapid increase in the level of educational attainment and skills among the workforces of emerging and developing economies.

In the Porto Social Commitment of 7 May 2021, the European Parliament, the Council of the EU, the European social partners and civil society organisations endorsed the target that at least 60% of all adults should participate in training every year by 2030.

The right to education, training and lifelong learning is enshrined in the European Pillar of Social Rights (Principle 1) which stipulates that ‘everyone has the right to quality and inclusive education, training and lifelong learning in order to maintain and acquire skills that enable them to participate fully in society and manage successfully transitions in the labour market’. Activities and initiatives at the European level provide support to national institutions and individuals to increase the participation of adults in learning and training activities.

The European Skills Agenda outlines a 5-year plan to help individuals and businesses develop more and better skills and to put them to use. Actions of the skills agenda also refer to tools and initiatives to support people along their journey of lifelong learning.

Within the European employment strategy Council decision (EU) 2020/1512 revised the employment guidelines. Guideline 6 concerns ‘enhancing labour supply and improving access to employment, skills and competences’. Among other things, this guideline calls on Member States to help everyone to anticipate and better adapt to labour market needs, in particular through continuous upskilling and reskilling.

Explore further

Other articles

- Adult learning - participants

- Adult learning statistics - characteristics of education and training

- Adult learning - reasons for not participating

- Statistics on continuing vocational training in enterprises

- Education and training in the EU — facts and figures

- EU labour force survey statistics — online publication

Database

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Adult learning (trng)

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

Thematic section

Methodology

Metadata

- Participation in education and training (based on EU-LFS) (reference metadata – trng_lfs_4w_esms)

- Adult education survey (reference metadata – trng_aes_12m_esms)

Manuals and other methodological information