Archive:European Neighbourhood Policy - East - labour market statistics

Data extracted in April 2021.

Planned article update: March 2022.

Highlights

In 2019, the gender gap for employment rates was lower in four of the European Neighbourhood Policy-East countries than in the EU; it was only higher in Armenia and Georgia.

Armenia and Georgia recorded the highest youth unemployment rates among the European Neighbourhood Policy-East countries in 2019. In Armenia, youth unemployment was 34.4% for women and 31.2% for men, while in Georgia it was 32.9% and 28.9% respectively.

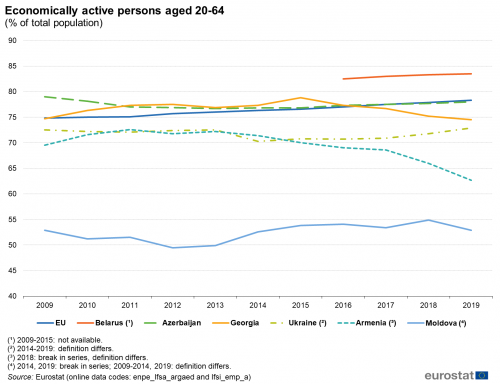

Economically active persons aged 20-64, 2009-2019

This article is part of an online publication; it presents information on a range of labour force statistics for the European Union (EU) and the six countries that together form the European Neighbourhood Policy-East (ENP-East) region, namely, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Data shown for Georgia exclude the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia over which Georgia does not exercise control and the data shown for Moldova exclude areas over which the government of the Republic of Moldova does not exercise control. The latest data for Ukraine generally exclude the illegally annexed Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol and the territories which are not under control of the Ukrainian government (see footnotes for precise coverage).

The article presents a range of labour market indicators such as activity rates, employment rates, an analysis of employment by economic activity and by professional status, and statistics on unemployment.

Full article

Activity rates

The economically active population, also known as the labour force, comprises employed and unemployed persons. The labour force also includes people who were not at work but had a job or business from which they were temporarily absent, for example because of illness, holidays, industrial disputes, education or training.

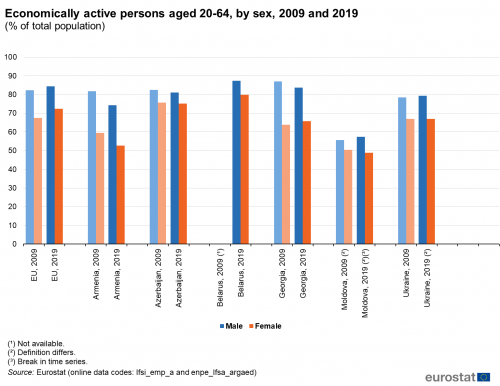

Figure 1 shows the proportion of the economically active population aged 15-64 as a time series over the period 2009-2019. Figure 2 compares the data for 2009 and 2019 (or the most recent year available), disaggregated to show the activity rates for men and women. Since some of the ENP-East countries’ data on the labour force is compiled using definitions that differ from EU standards, it is generally more useful to compare country data over time, rather than compare between countries.

In Azerbaijan, the economically active population trended upwards from 70.0 % in 2009 to 72.6 % in 2019. Male activity increased from 73.0 % to 75.0 %; female activity from 67.2 % to 70.2 %. Although this pattern is often seen in countries where total labour market participation is growing, thereby reducing the gender gap, it does not occur elsewhere in the ENP-East countries.

Moldova’s total economically active population increased during 2009-2019 from 47.7 % of the total to 49.4 %. Male participation grew from 50.0 % in 2009 to 53.0 % in 2019. Meanwhile, female participation only increased from 45.3 % to 46.0 %. Changes in the definition occurred during this period. Ukraine showed a similar pattern of a greater increase in the male than the female participation, although a change in definition may affect the overall trend. Male participation grew from 72.4 % to 74.5 % in 2019, female from 62.3 % in 2009 to 63.2 %, making a total increase from 67.1 % in 2009 to 68.7 % in 2019. Armenia also showed a greater increase in male participation over 2009-2019, growing from 71.3 % to 80.6 %, while female participation rose by much less from 53.5 % to 55.6 %. Total participation initially rose from 61.6 % in 2009 before declining from 2014 onwards. While 2018 data may be affected by a definition change, 2019 data showed an increase to 67.2 %.

In the remaining ENP-East countries, total labour market participation fell over the period. In Belarus, participation was 79.9 % in 2009, made up of 73.5 % male participation and 86.7 % female participation. By 2019, the positions had reversed, with male participation up to 81.7 % and female down to 75.1 %. The total decreased to 78.3 %. In Georgia, total participation fell from 68.6 % in 2009 to 60.4 % in 2019. All of this fall occurred in the last year: the 2018 figure was 70.5 %. A fall in labour market participation is often associated with a rise in unemployment; however, Figure 6 below shows that this is not the case here. Female participation in Georgia fell from 58.9 % to 54.3 %. This decline was less than for men: participation was 79.6 % in 2009 but 66.8 % in 2019.

Female economic activity grew faster than male in the EU: female participation was 63.3 % and male 77.0 % in 2009, giving a total activity rate of 70.1%. By 2019, female participation had grown to 67.9 % and male to 79.0 %, for a total of 73.4 %.

(% of total population)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_emp_a) and (enpe_lfsa_argaed)

(% of total population)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_emp_a) and (enpe_lfsa_argaed)

Employment rates

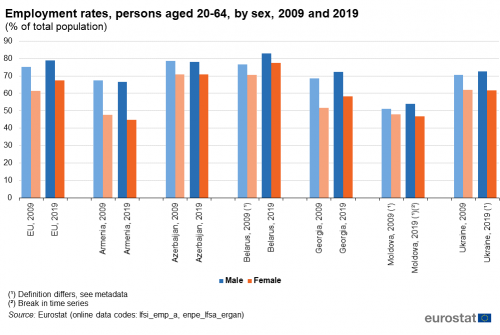

In line with international standards, the EU European Union labour force survey (EU LFS) defines persons in employment as those aged 15 and over, who, during the reference week, performed some work, even for just one hour per week, for pay, profit or family gain. Employment statistics are frequently reported as employment rates to discount the changing size of countries’ populations over time and to facilitate comparisons between countries of different sizes. These rates are typically published for the working age population, which is generally considered to be those aged 15-64 years, as well as for those aged 20-64 years, in order to take account of the increasing proportion of young people who remain in education. The data shown in Figure 3 shows employment rates in 2009 and 2019 by gender for the 20-64 year age group.

Since people in employment make up a large part of the labour force, the two statistics often increase or decrease together. This relationship is, however, not often observed in the ENP-East statistics during the period 2009-2019. The employment situation in ENP-East countries that showed an increase in labour force participation over this period (see above) are examined first.

In Azerbaijan, male employment fell from 78.7 % in 2009 to 77.9 % in 2019. Female employment remained at the same level, with only a slight increase from 70.8 % to 70.9 %. The gender gap, the difference between male and female employment rates, declined from 7.9 to 7.0 percentage points as a result. In Moldova, male employment increased from 51.2 % to 53.9 %, while female employment declined from 48.0 % in 2009 to 46.8 % in 2019. The gender gap increased from 3.2 to 7.1 percentage points.

In Ukraine, male employment increased from 70.5 % to 72.7 % over 2009-2019, while female employment declined from 62.1 % to 61.6 %. The gender gap consequently increased from 8.4 to 11.1 percentage points. Armenia saw a decline in the employment rate of both sexes over the period: in male employment from 67.4 % to 66.6 % and in female employment from 47.8 % to 44.8 %, leading to a gender gap increase from 19.6 to 21.8 percentage points. This was by far the highest among the countries in the region in 2019.

Female employment in Belarus in 2009 was at 70.7 % and in 2019 at 77.4 %. Male employment increased from 76.5 % to 83.0 %. The gender gap remained almost stable, falling slightly from 5.8 percentage points in 2009 to 5.6 percentage points ten years later. In Georgia, male employment increased from 68.6 % to 72.3 % in 2009, while female employment grew from 51.7 % to 58.3 % in 2019. The gender gap therefore fell over the period from 16.9 percentage points to 14.0 percentage points.

During the period 2009-2019, EU male employment rate rose from 75.1 % to 79.0 %. This remained considerably higher than the corresponding rate for women, which was 61.4 % in 2009 and 67.3 % in 2019. The gender gap consequently fell from 13.7 percentage points in 2009 to 11.7 percentage points in 2019.

(% of total population)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_emp_a) and (enpe_lfsa_ergan)

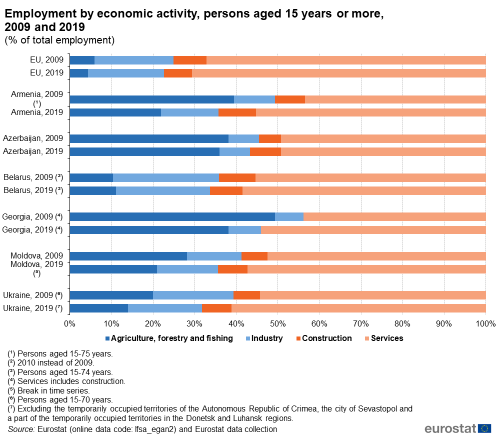

Employment by economic activity

Figure 4 shows an analysis of the structure of employment for 2009 and 2019. In all of the ENP-East countries, services accounted for the largest proportion of the workforce in both 2009 and 2019. In 2019, services accounted for more than half of all people employed in all the economies of the region except Azerbaijan, where the share was only slightly less than half.

A relatively high share of the total workforce was employed in agriculture, forestry and fishing in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Moldova; this sector was the second largest employer in each of these countries. Belarus and Ukraine had higher shares of industrial employment, although these fell in both countries over the period 2009-19. The share of industry in employment grew in Armenia, Georgia and Moldova. Construction employment tends to be highly cyclical. Sector shares in employment ranged from 5.4 % in Azerbaijan in 2009 to 9.0 % in Armenia in 2019; in Georgia, construction employment is not separately identified but instead incorporated into the services sector.

A comparison of the employment structure in 2009 (2010 for Belarus) with that in 2019 shows a fall in the share in agriculture, forestry and fishing in five of the ENP-East countries, although the decline was small in Azerbaijan. There was a marginal increase recorded in Belarus. By contrast, services accounted for an increase in their share of the workforce in all ENP-East countries over 2009-2019, although in Azerbaijan the share was almost unchanged over the period.

There was a rapid restructuring of the labour markets in Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine between 2009 and 2019 (in Ukraine this may in part reflect a change in geographical coverage of data, and in Moldova, a break in the data series). In Armenia the proportion of people working in agriculture, forestry and fishing activities fell strongly, while the shares of the workforce employed in all the other main sectors increased, most strongly in services and to a lesser extent in industry and construction.

Within the EU, services accounted for 70.6 % of persons employed (aged 15 or more) in 2019, substantially higher than in the ENP-East countries. The share of services within EU employment rose by 3.5 percentage points from 2009 to 2019.

(% of total employment)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egan2) and Eurostat data collection

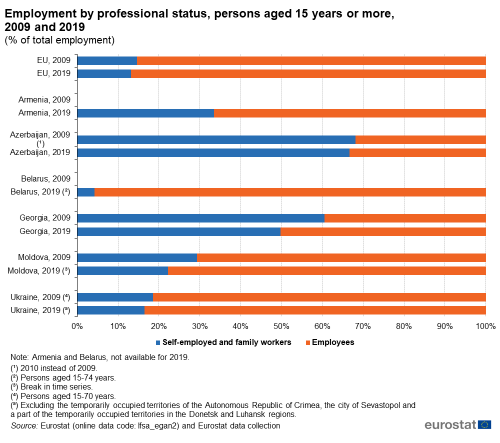

Employment by professional status

The share of self-employment and family work was 66.7 % of the total workforce in Azerbaijan in 2019; in Georgia it was 49.7 %; in Armenia 33.5 %; and in Moldova 22.2 %. These figures reflect, to some degree, the relative weight of agricultural activities in each of these countries, with work spread across numerous small-scale, family-run farms and cooperatives. By contrast, in Ukraine self-employment and family workers represented 16.5 % of the workforce, and in Belarus 4.3 %.

Georgia saw a decrease in the share of self-employment and family work of almost 11 percentage points in the period 2009-2019 and Moldova a fall of more than 7 percentage points. In the other two ENP-East countries for which data are available for both years, Azerbaijan and Ukraine, the decline was minor in both.

Self-employed and family workers made up 13.2 % of the labour force in the EU in 2019. This corresponded to a fall in the share of self-employed and family workers in total employment by around 1.4 percentage points over the decade form 2009.

(% of total employment)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_egaps) and Eurostat data collection

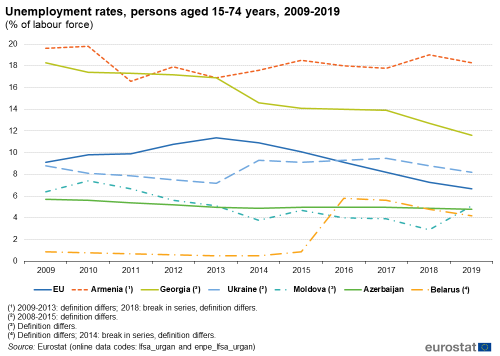

Unemployment rates

Eurostat publishes unemployment statistics based on the definition of unemployment provided by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), for which there are three criteria: being without work, actively seeking work, and being available for work. Therefore, people working only a few hours a week and who wish to work more, known as the underemployed, are excluded from the unemployment figures. In countries that have significant underemployment, understanding of the unemployment data benefits from being read in conjunction with employment data; for example, statistics on part-time work or on total hours worked may shed light on trends in underemployment.

In general, the unemployment rate begins to rise only after an economic downturn has occurred. Once the economy starts to pick up again, employers usually remain cautious about hiring new workers and there may be a lag before the unemployment rate start to fall. In addition, people who were formerly economically inactive may decide to join or rejoin the labour force, initially increasing the unemployment figures. This tendency can be seen in some ENP-East countries that were affected by the global financial and economic crisis, as their unemployment rates peaked in 2009 or 2010, after which there were signs that the labour market was moving to a more balanced position.

Data for the ENP-East countries on unemployment rates as a percentage of the labour force over the period 2009-2019 is shown in Figure 6. Comparison of the data between the labour markets of the ENP-East countries may be difficult, either because of breaks in the data series or consistent differences from the standard definition of the statistic.

Azerbaijan recorded a relatively low unemployment rate and a slow but almost uninterrupted decrease in its unemployment rate over the period 2009-2019. From its peak in 2009, the unemployment rate in Georgia fell each year through to 2019, but it has remained high. Similarly, Moldova's unemployment declined in most years after 2010; even after an increase compared with 2018, 2019 unemployment was lower than ten years previously. Although unemployment in Armenia has also declined somewhat from its 2010 high point, it remains at a high level. Ukraine’s unemployment finished the period little changed from its beginning; the events of 2014 and 2015 can perhaps be seen in higher unemployment in the period 2014-2017, although changes in the data definition also occurred at the time.

Unemployment in Belarus was higher in 2019 than in 2009, although the country’s data from 2009-2015 are not considered comparable as they are based upon registered unemployment, whereas data since 2016 are based on a survey.

While the global financial and economic crisis led to the largest contraction in its economic activity being recorded in 2009, the EU’s unemployment rate continued to rise through 9.1 % in 2009 to peak at 11.4 % in 2013, before falling continuously to 6.7 % in 2019.

(% of labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_urgan) and (enpe_lfsa_urgan)

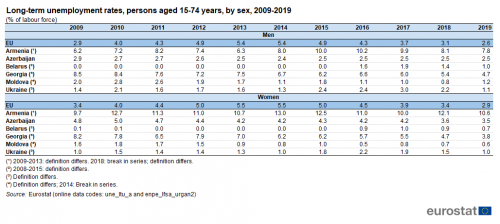

Long-term unemployment, measured as those unemployed for more than 12 months, is often viewed as a key indicator by policymakers because it provides information in relation to structural weaknesses that may affect social cohesion and, ultimately, economic growth. Data are shown by gender in Table 1. Note that the very low rates shown for Belarus before 2016 are a result of the data at the time being based on registered unemployment.

In ENP-East countries, particularly low rates of less than 2.0 % were recorded in Belarus from 2016 and in Moldova for both men and women. Azerbaijan has had consistent fairly low rates of long-term unemployment for men and somewhat higher rates for women. Ukraine also showed low rates for the age group 15-70, except for men during the period 2015-2018 and for women in 2016. In contrast, long-term unemployment rates for both men and women in Georgia declined considerably over 2009-2019, although there was a large increase for women in 2012 and smaller ones for men in 2013 and 2016. In Armenia, the share of the labour force that had been unemployed for more than 12 months rose from 2009 to 2014/2015, before declining again; long-term unemployment was higher in 2019 than 2009 for both men and women. Note that Armenia’s data has had definition changes.

In the EU, youth and long-term unemployment appear to be more susceptible to cyclical economic changes than overall unemployment. In 2019, the long-term unemployed in the EU made up 2.6 % of the male labour force and 2.9 % of the female labour force.

(% of labour force)

Source: Eurostat (une_ltu_a) and (enpe_lfsa_urgan2)

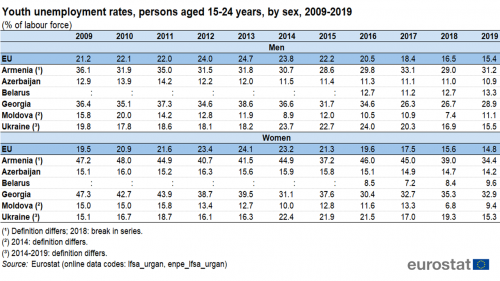

Table 2 provides data on the youth unemployment rate.

Across the ENP-East countries, youth unemployment rates were consistently higher than overall unemployment rates. The highest youth unemployment and the greatest difference from overall unemployment in 2019 occurred in Armenia and Georgia. In Georgia, the youth unemployment rate for women was 32.9 % in 2019 and for men, 28.9 %, while the rate for the whole labour force was 11.6 %. Armenia unemployment stood at 31.2 % among young men and 34.4 % among young women in 2019. The next highest youth unemployment rates in the ENP-East countries in 2019 occurred in Ukraine, at 15.5 % for men and 15.3 % for women. Youth unemployment rates in Azerbaijan were 10.9 % for young men and 14.2 % for young women. The lowest unemployment rates for young women were in Moldova and Belarus; for young men in Azerbaijan and Moldova. Youth unemployment for women was higher than for men in Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia, and at similar rates in Ukraine.

In 2009, 21.2 % of the EU’s male labour force aged 15 to 24 years and 19.5 % of the corresponding female labour force was without work. These figures had fallen to 15.4 % and 14.8 % respectively by 2019. Nevertheless, youth unemployment in 2019 remained much higher than the average rate recorded for the whole labour force, at 6.7 %.

(% of labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_urgan) and (enpe_lfsa_urgan)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The data for ENP-East countries are supplied by and under the responsibility of the national statistical authorities of each country on a voluntary basis. The data that are presented in this article result from an annual data collection cycle that has been established by Eurostat. These statistics are available free-of-charge on Eurostat’s website, together with a range of different indicators covering most socio-economic areas.

The main source for European labour force statistics is the European Union labour force survey (EU LFS). This household survey is carried out in all EU Member States in accordance with European legislation; it provides figures at least each quarter.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value; |

| – | not applicable. |

Context

Labour market statistics are increasingly used to support policymaking and to provide an opportunity to monitor participation in the labour market. In the aftermath of the global financial and economic crisis, these statistics are used to monitor the effects of the crisis on labour markets, which tend to lag behind changes in economic activity.

Social policymakers often face the challenge of remedying uncertainty in employment and high unemployment by designing ways to increase employment opportunities for specific groups in society, such as the young, those having working in certain economic activities, or those living in low employment regions.

The slow pace of recovery from the financial and economic crisis in the EU and mounting evidence of rising unemployment led the European Commission to propose an employment package in April 2012. This considered how employment policies intersect with a number of other policy areas in support of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. It identified the EU's biggest job potential areas and the most effective ways for EU countries to create more jobs.

In December 2012, in the face of high and still rising youth unemployment in several EU Member States, the European Commission proposed a Youth employment package (COM(2012) 727 final). Efforts to reduce youth unemployment continued in 2013 as the European Commission presented a Youth employment initiative (COM(2013) 144 final) designed to reinforce and accelerate measures outlined in the Youth employment package. It aimed to support, in particular, young people not in education, employment or training in regions with a youth unemployment rate above 25 %. There followed another Communication Working together for Europe's young people — A call to action on youth unemployment (COM(2013) 447 final) which was designed to accelerate the implementation of the youth guarantee and provide help to EU Member States and businesses so they could recruit more young people.

In June 2016, the European Commission adopted a Skills Agenda for Europe (COM/2016/0381 final) under the heading ‘Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness’. This was intended to ensure that people develop the skills necessary for now and the future, in order to boost employability, competitiveness and growth across the EU.

These measures to develop Member States’ employment support systems work through the open method of coordination (OMC), an inter-governmental voluntary process used to support common objectives through cooperation, peer reviews and Commission surveillance. These policies are, in 2021, under review through the European Semester process.

In March 2020, the European Commission presented a joint policy proposal for Eastern Partnership policy beyond 2020: Reinforcing Resilience - an Eastern Partnership that delivers for all. This is intended to succeed the 2015 review of the European Neighbourhood Policy (SWD(2015) 500 final).

In cooperation with its ENP partners, Eurostat has the responsibility ‘to promote and implement the use of European and internationally recognised standards and methodology for the production of statistics, necessary for developing and monitoring policy achievements in all policy areas’. Eurostat undertakes the task of coordinating EU efforts to increase the statistical capacity of the ENP countries. Additional information on the policy context of the ENP is provided here.

Direct access to

Books

Leaflets

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2019 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2018 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2016 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2015 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2014 edition

- International trade for the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2016 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy-East countries — Statistics on living conditions — 2015 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — Key economic statistics — 2014 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — Labour market statistics — 2014 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — Youth statistics — 2014 edition

- Population and social conditions (enpe_pop)

- Labour market (enpe_labour)

- Active population (enpe_lfsa_act)

- Employment (enpe_lfsa_emp)

- Unemployment (enpe_lfsa_unemp)

- Labour market (enpe_labour)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Employment and activity - LFS adjusted series (lfsi_emp)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Eastern European Neighbourhood Policy countries (ENP-East) (ESMS metadata file — enpe_esms)

- LFS main indicators (ESMS metadata file — lfsi_esms)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)