Archive:The EU in the world - environment

- Data extracted in March 2016. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: June 2018.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2016.

The article focuses on environmental issues in the European Union (EU) and in the 15 non-EU members of the Group of Twenty (G20). It provides information on air emissions, freshwater resources, waste generation and treatment, and protected areas (habitats). It gives an insight into the state of the environment in the EU and in the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

(% share of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (env_ac_tax) and OECD (Environment statistics)

(million tonnes of CO2-equivalents)

Source: Eurostat (env_air_gge) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

(%)

Source: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); South Africa's second national communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2011. UNFCCC data has been used for the EU-28 for comparability reasons. However data is also available in Eurostat ( (env_air_gge))

(% of treated waste)

Source: Eurostat (env_wasmun) and OECD (Environment, Waste)

(m3 per inhabitant)

Source: Eurostat (env_wasmun) and OECD (Environment, Waste)

(m3 per inhabitant)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind), the World Bank (World Development Indicators) and United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Population Division)

Main statistical findings

Environmental taxes

Turkey had the highest revenue from environmental taxes relative to GDP

An environmental tax is one whose tax base is a physical unit (or a proxy of one) of something that has a proven, specific negative impact on the environment. Examples are taxes on energy, transport and pollution, with the first two dominating revenue raised through these taxes in nearly all countries. As well as raising revenue, environmental taxes may be used to influence the behaviour of producers or consumers.

In 2013, the EU-28 Member States raised EUR 332 billion of revenue from environmental taxes, equivalent to 2.5 % of GDP. Figure 1 compares the relative importance of environmental taxes between the G20 members and shows how these developed between 2003 and 2013. Among the G20 members, the highest revenue from environmental taxes, relative to GDP, was in Turkey where these taxes were equivalent to 4.1 % of GDP in 2013. The negative value for Mexico reflects the system used to stabilise motor fuel, which leads to subsidies when oil prices are high. Between 2003 and 2013, the ratio of environmental taxes to GDP fell in most G20 members, the exceptions being South Africa, China and India.

Air emissions

Data relating to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are collected under the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement linked to the UNFCCC: it was adopted in 1997 and entered into force in 2005. A total of 192 parties subsequently ratified the Protocol; the United States did not ratify it and Canada subsequently announced its withdrawal. Under the Protocol a list of industrialised and transition economies — referred to as Annex I parties — committed to targets for the reduction of six greenhouse gases or groups of gases, namely CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulphur hexafluoride.

The G20 members that are Annex I parties are signalled in Figures 2 and 3 from those G20 members that are not. The EU is an Annex I party and was composed of 15 Member States at the time of adoption of the Protocol under which the EU agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 8 % during the period 2008–12 when compared with their 1990 levels. Among other environmental commitments, the EU-28 has subsequently committed to a 20 % reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020.

The second commitment period (2013–20) based on the Doha Amendment to the Protocol has not entered into force. In 2015 during the UN Climate Change Conference held in in Paris the then 196 parties adopted the Paris Agreement that aims at governing emission reductions from 2020 onwards through national commitments. The Paris Agreement, still under ratification [1], aims at ‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2ºC above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels’ [2].

Between 1990 and 2012 greenhouse gas emissions fell in the EU-28 and in Russia

Emissions of different greenhouse gases are converted to CO2 equivalents based on their global warming potential to make it possible to compare and aggregate them. Total greenhouse gas emissions by Annex I parties in 2012 were around 17.0 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalents, 10.6 % lower than the level in the base year (1990 for most parties).

Among G20 countries, greenhouse gas emissions fell only in Russia (– 32 %) and the EU-28 (– 22 %) between 1990 and 2012 (see Figure 2). Emissions in South Korea, Turkey and Indonesia (1990–2000) more than doubled, while emissions also increased by at least 50 % for China (1994–2005), Saudi Arabia (1990–2000) Mexico (1990–2006) and Brazil (1990–2005).

Figure 3 provides an analysis of the source of greenhouse gas emissions in 2012 — note that the data for nearly all of the G20 members that are not Annex I parties relate to relatively distant reference years. ‘Energy supply’ was the major source of GHG emission in the EU-28 and had at least a 30 % share in most of the G20 members. The exceptions were Turkey and Indonesia (2000 data) where it was ‘energy use’ and also Argentina (2000 data) and Brazil (2005 data) where most of the emissions came from ‘agriculture’. ‘Energy use’ accounted for more than one third of the GHG emissions in South Korea, Japan and China (2005 data) while ‘transport’ was responsible for more than a fifth of the GHG emissions of Canada, the United States and Mexico (2006 data).

Figure 4 provides an analysis of emission intensities of carbon dioxide (CO2) for 2002 and 2012. These intensities varied considerably between G20 members reflecting, among other factors, the structure of each economy (for example, the relative importance of heavy, traditional industries), the national energy mix (the share of low or zero-carbon technologies compared with the share of fossil fuels), heating and cooling needs and practices, and the propensity for motor vehicle use.

Saudi Arabia (2011 data), Australia, the United States and Canada all had more than 15.0 tonnes per inhabitant of CO2 emissions in 2012. With 7.4 tonnes per inhabitant, the EU-28 belonged to an intermediate group where emission varied from 5.0 to 13.0 tonnes per inhabitant including South Korea, Russia, Japan, South Africa (2011 data) and China. All the other G20 members had CO2 emission under 5.0 tonnes per inhabitant. Between 2002 and 2012, the intensity of emissions decreased only in the United States, Canada, the EU-28, Australia and Japan. In all the other G20 members, the emission increased from less than 5.0 % in Mexico (2011 data) to more than 50.0 % in Turkey and Indonesia (2011 data) and peaking at 132.6 % in China (2011 data).

China’s production of ozone depleting substances was greater than the production of all other G20 members combined

The Gothenburg Protocol is one of several concluded under the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Convention on Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution; it aims to control transboundary air pollution and associated health and environmental impacts, notably acidification, eutrophication and ozone pollution. Ozone depleting substances (ODS) contribute to ozone depletion in the Earth’s atmosphere. These substances are listed in the Montreal Protocol which is designed to phase out their production and consumption.

In the G20 members there has been a considerable reduction in the consumption of ODS in recent years. By 2014, the EU-28 had a negative consumption of ODS, indicating that exports and destruction of these substances were greater than the level of production plus imports (see Figure 5). With an increase of over 60 % between 2004 and 2014, China’s consumption of ODS has become greater in 2014 than the consumption in all other G20 members combined.

Waste

South Korea recycled more than half of its municipal waste

The management and disposal of waste can have a serious environmental impact, taking up space and potentially releasing pollution into the air, water or soil. Municipal waste is waste that is collected by or on behalf of municipalities, by public or private enterprises, which originated from households, commerce and trade, small businesses, office buildings and institutions (schools, hospitals and government buildings). Also included is waste from selected municipal services (such as park and garden maintenance and street cleaning services) if managed as waste. For areas not covered by a municipal waste collection scheme the amount of waste generated is estimated.

Landfilling is the final placement of waste into or onto the land in a controlled or uncontrolled way and covers both landfilling in internal sites (by the generator of the waste) and in external sites. Incinerating is the controlled combustion of waste with or without energy recovery. Recycling is any reprocessing of waste material in a production process that diverts it from the waste stream, except reuse as fuel. Both reprocessing as the same type of product and for different purposes should be included. Recycling at the place of generation should be excluded. Composting is a biological process that submits biodegradable waste to anaerobic or aerobic decomposition and that results in a product that is recovered and can be used to increase soil fertility.

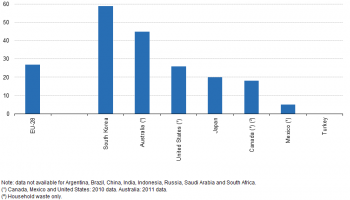

Among the G20 members with data available (see Table 1), Japan reported the most frequent use of incineration to treat municipal waste (78 %) while Mexico (95 %) and Turkey (99 %) reported the most frequent use of landfill. In South Korea, more than half (59 %) of the municipal waste was recycled (see Figure 7), followed by Australia (45 %) (2011 data). The EU-28 and the United States (2011 data) both recorded shares of just over one quarter.

The amount of municipal waste generated ranged from 734 kg per inhabitant in the United States (2010 data) to 25 kg per inhabitant in India (2012 data), with Australia (2011 data) and Russia (2012 data) over the 500 kg per inhabitant threshold and Indonesia (31 kg) (2011 data) closer to India’s minimum. Around 478 kg of municipal waste per inhabitant was estimated in the EU-28 for 2013, which also produced the highest amount of municipal waste (240.9 million tonnes) within the G20 members. This volume was close to the figure for the United States (227.6 million tonnes) (2010 data) but much higher than the Chinese municipal waste production (note that data for China are only referenced for the year 2012 and only cover urban areas).

Water use

Freshwater withdrawals refer to total water withdrawals, not counting evaporation losses from storage basins. Withdrawals also include water from desalination plants in countries where they are a significant source.

G20 members accounted for approximately two thirds of all freshwater withdrawals worldwide; India, China, the United States and the EU-28 together accounted for more than half. Relative to population size (see Figure 8), the United States had the highest annual freshwater withdrawals, its 1 498 m3 per inhabitant was far higher than the 1 090 m3 recorded in Canada which had the next highest withdrawals.

Figure 9 presents the share of the total population with access to improved water sources which include piped water in premises and other improved drinking water sources. All G20 members presented a coverage population connected to improved water sources of more than 85 %. The EU-28 presented a 99.8 % share and in Australia, Japan, Turkey, Canada, the United States and Argentina it was also over 99 %. Indonesia was the only G20 member that had a coverage below the world average.

Protected areas

In the EU-28 around 25.1 % of the surface area is designated as a protected area

Terrestrial and marine areas may be protected because of their ecological or cultural importance and they provide a habitat for plant and animal life. Protected areas are areas of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means. Marine protected areas are any area of intertidal or sub tidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or the entire enclosed environment. Territorial waters extend at most 12 nautical miles (1 nautical mile is equal to 1 852 metres) from the baseline of a coast (normally the low-water line).

In the EU-28 around 25.1 % of the surface area (land area and inland water bodies) was designated as a protected area as of 2014, along with 28.9 % of territorial waters (see Figures 10 and 11). Among the other G20 members, the largest shares of surface area that were protected were in Brazil and Saudi Arabia, with Brazil having the largest protected area in absolute terms (2.4 million km2 in 2014). A large proportion of marine areas around the United States and Australia had protected status and these were also the largest protected marine areas in absolute size, each over 400 thousand km2. Between 2000 and 2014, almost all G20 members reported a rise in the proportion of their protected terrestrial area, with large increases (above 5 percentage points – pp) in Brazil, Mexico, Australia and the EU-28. By contrast, Saudi Arabia and Turkey’s share of protected terrestrial areas was the same in 2000 and 2014. As for the share of marine protected areas, there was an increase in all the G20 members from 2000 to 2014, that where above 10 pp in Australia, South Africa and the EU-28.

Data sources and availability

The statistical data in this article were extracted during March 2016.

The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes global — standards. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU data

Some of the indicators presented for the EU have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this article and data that is subsequently downloaded. In most cases EU data is derived from international sources which use a common methodology, making the data more comparable within the G20 members.

G20 members from the rest of the world

For the 15 non-EU G20 members, the data presented have been extracted from a range of international sources, namely the OECD, the United Nations Environment Programme, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the World Bank. For some of the indicators shown a range of international statistical sources are available, each with their own policies and practices concerning data management (for example, concerning data validation, correction of errors, estimation of missing data, and frequency of updating). In general, attempts have been made to use only one source for each indicator in order to provide a comparable analysis between the members.

Context

Dramatic events around the world frequently propel environmental issues into the mainstream news, from wide scale floods or forest fires to other extreme weather patterns, such as hurricanes. The world is confronted by many environmental challenges, for example tackling climate change, preserving nature and biodiversity, or promoting the sustainable use of natural resources. The inter-relationship between an economy and a society on one hand and their surrounding environment on the other hand is a factor for many of these challenges and underlies the interest in sustainable growth and development, with positive economic, social and environmental outcomes.

See also

- All articles on the environment

- All articles on the non-EU countries

- Other articles from The EU in the world

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- The EU in the world 2015

- The European Union and the African Union — A statistical portrait — 2015 edition

- Energy, transport and environment indicators — 2015 edition

- Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2015 edition

- Sustainable development in the European Union — Key messages — 2015 edition

- Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) — A statistical portrait — 2014 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

Database

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions (source: EEA) (env_air_gge)

- Waste (env_was), see:

- Waste streams (env_wasst)

- Municipal waste (env_wasmun)

- Environmental tax revenues (env_ac_tax)

- Population change — Demographic balance and crude rates at national level (demo_gind)

Dedicated section

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

![]() Environment: tables and figures

Environment: tables and figures

External links

- OECD

- United Nations

- World Bank

Notes

- ↑ At the time of drafting of this publication.

- ↑ UNFCCC, Paris Agreement.