Archive:Passenger transport statistics

- Data from July and October 2014. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: January 2016.

2002 and 2012 (¹)

(% of total inland passenger-km) - Source: Eurostat (tran_hv_psmod)

(Index 2000 = 100) - Source: Eurostat (tran_hv_pstra)

(Passenger-km per inhabitant) - Source: Eurostat (rail_pa_typepkm) and (demo_gind)

(Million passengers) - Source: Eurostat (avia_paoa)

- Source: Eurostat (ttr00012), (demo_gind) and (mar_pa_aa)

This article provides details relating to recent trends for passenger transport statistics within the European Union (EU). It presents information on a range of passenger transport modes, such as road, rail, air and maritime transport. Among these, the principal mode of passenger transport is that of the passenger car, fuelled by a desire to have greater mobility and flexibility. The high reliance on the use of the car as a means of passenger transport across the EU has contributed to an increased level of congestion and pollution in many urban areas and on many major transport arteries.

Main statistical findings

Passenger cars accounted for 83.3 % of inland passenger transport in the EU-28 in 2012, with motor coaches, buses and trolley buses (9.2 %) and trains (7.4 %) both accounting for less than a tenth of all traffic (as measured by the number of inland passenger-kilometres (pkm) travelled by each mode) — see Table 1.

Between 2002 and 2012 there was a marked increase in the relative importance of the use of passenger cars among many of the Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007, in particular in Bulgaria, Estonia, Slovakia and Lithuania; there was also a substantial increase in the use of passenger cars in Turkey. By contrast, the relative importance of cars as a mode of inland passenger transport fell in eight of the EU-15 Member States. The most sizeable reductions in the relative importance of passenger cars between 2002 and 2012 were recorded in Italy (the share of cars in total inland passenger transport fell 4.4 percentage points), Luxembourg (-2.7 percentage points) and the United Kingdom (-2.4 points), while the relative importance of the car also fell in three more of the largest EU Member States — Germany, Spain and France. The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (-3.5 points) and Switzerland (-2.4 points) also recorded a contraction in the relative importance of passenger cars for inland passenger transport.

In the vast majority of EU Member States, constant price gross domestic product (GDP) grew faster than the level of inland passenger transport between 2002 and 2012 — see Table 2. Note that in some years the level of inland passenger transport and / or the level of GDP declined (for example, in 2009 when the financial and economic crisis was at its height). It should also be underlined that the indicator refers only to inland transport by car, motor coach, bus and trolley bus, or train, and that a significant proportion of international passenger travel is accounted for by maritime and air transport passenger services, while in some countries national (domestic) maritime and air transport passenger services may also be noteworthy.

Between 2000 and 2007, constant price GDP grew 7.9 % faster than the rate of growth of inland passenger transport in the EU-28. However, the effects of the global financial and economic crisis led to a reduced level of economic activity and in 2009 the index of inland passenger transport relative to GDP had almost returned to its level of 2000, before falling again through to 2012, when it stood some 5.9 % lower than in 2000.

Across the EU Member States, the relationship between economic growth and the volume of inland passenger transport varied considerably. The rate of change in constant price GDP was 44.3 % higher than that for inland passenger transport in Slovakia, while in Latvia and the Czech Republic the difference was more than 30 %. By contrast, there were seven Member States where the volume of inland passenger transport grew at a faster pace than GDP, with three cases where the difference in the rates of growth of inland passenger transport and GDP was more than 10 % by 2012, namely Cyprus (12.6 %), Poland (15.3 %) and Greece (29.8 %) — figures for the latter are influenced by the marked downturn in economic activity as a result of the financial and economic crisis. Among the non-member countries shown in Table 2, Turkey (latest data are for 2011) was the only country where the index of inland passenger transport relative to GDP fell by more than the EU-28 average. There was almost no difference in the pace of development of GDP and inland passenger transport in Iceland and Switzerland, while inland passenger transport grew at a faster pace than GDP in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

Road passengers

Reliance on cars for passenger transport was particularly high in Lithuania, Portugal and the Netherlands, where cars accounted for at least 88 % of all inland passenger-kilometres in 2012; a relatively high usage of passenger cars was also recorded for Norway and Iceland (also both above 88 %). Passenger cars accounted for less than 75 % of all inland passenger-kilometres in the Czech Republic and Hungary, as well as in Turkey (which recorded by far the lowest share for passenger cars, at 64.6 %); note there was a break in series for all three of these countries.

More than one fifth of the inland passenger-kilometres travelled in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (20.7 %) and Hungary (22.2 %) were by motor coaches, buses and trolley buses, a share that rose to over one third in Turkey (36.6 %). By contrast, among the EU Member States the relative importance of the use of motor coaches, buses and trolley buses was lowest in the Netherlands where this mode of transport accounted for just 3.0 % of the modal split, while in Germany, France and the United Kingdom their share was below 6 %.

Rail passengers

The modal share of trains in total inland passenger transport was highest in 2012 among the EU Member States in Austria (11.5 %), followed by Hungary and Denmark (both 10.1 %), France (9.5 %), Sweden (9.1 %) and Germany (9.0 %); the share of trains was substantially higher in Switzerland (17.2 %). Note that neither Cyprus nor Malta has a railway network and that all data in this section exclude the Netherlands for which the data are confidential.

Based on the latest data available (generally for 2013), there were 387 billion passenger-kilometres travelled on national railway networks of the EU-27 (including 2011 data for Belgium and 2012 data for Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Luxembourg, Hungary and Finland). This figure was considerably higher than the 25 billion passenger-kilometres travelled on international journeys (the comparison is based on the same reference years for each Member State) — see Table 3.

More than 70 % of all rail travel (national and international combined) in the EU-27 was accounted for by the four largest EU Member States, with France and Germany together accounting for 44 % of national rail travel within the EU-27 and 64 % of international rail travel. The number of international passenger-kilometres travelled by passengers in France in 2013 was more than twice the level for Germany (in 2012) which in turn recorded a figure that was more than twice as high as that for the United Kingdom.

In order to compare the relative importance of rail transport between countries, the data can be normalised by expressing the level of passenger traffic in relation to population (as shown in the right-hand side of Table 3). On average each inhabitant of France, Sweden, Austria, Germany and Denmark (data for the latter two countries refer to 2012) travelled more than 1 000 passenger-kilometres in 2013 on the national railway network; this was well below the average recorded in Switzerland (2 141 passenger-kilometres per inhabitant in 2013). By contrast, among the EU Member States in 2013 the lowest average distances travelled on national railway networks were recorded in Lithuania (85 passenger-kilometres per inhabitant) and Greece (75 passenger-kilometres in 2012), while the averages in Turkey (49 passenger-kilometres) and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (39 passenger-kilometres) were lower still.

In terms of international rail travel, the only EU Member States to report averages of more than 100 passenger-kilometres per inhabitant in 2013 were Luxembourg (data are for 2012), Austria, France and Belgium (data are for 2011), a level that was also surpassed in Switzerland. These figures may reflect, among others, the proximity of international borders, the importance of international commuters within the workforce, access to high-speed rail links, and whether or not international transport corridors run through a particular country.

Air passengers

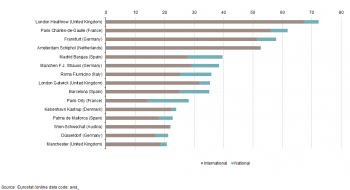

London Heathrow was the busiest airport in the EU-28 in terms of passenger numbers in 2013 (72.3 million), followed — at some distance — by Paris’ Charles de Gaulle airport (61.9 million), Frankfurt airport (57.9 million) and Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport (52.5 million) — see Figure 2. The overwhelming majority (at least 89 %) of passengers through the four largest airports in the EU were on international flights. By contrast, national (domestic) flights accounted for 30.1 % of the 39.7 million passengers carried through the EU’s fifth busiest passenger airport in 2013, namely Madrid Barajas. There were also relatively high proportions of passengers on national flights to and from Paris Orly (50.2 %), Roma Fiumicino (30.2 %) and Barcelona airport (28.9 %).

Some 842 million passengers were carried by air in 2013 in the EU-28 — see Table 4. Having peaked at 803 million passengers in 2008, the number of air passengers in the EU-28 fell by almost 6 % in 2009 at the height of the financial and economic crisis, before rebounding in 2010 and 2011. There was muted growth (0.7 %) in air passenger numbers in 2012, followed by a somewhat higher rate of change in 2013 (up 1.7 %). As a result, the number of air passengers carried in the EU-28 in 2013 was almost 5 % higher than its pre-financial and economic crisis peak reached in 2008.

The United Kingdom reported the highest number of air passengers in 2013, with 210 million or an average of 3.3 passengers per inhabitant (which was about double the EU-28 average). Relative to population size, the importance of air travel was particularly high for the holiday islands of Malta and Cyprus (9.5 and 8.1 passengers carried per inhabitant) in 2013, as well as in Iceland (9.9) and Norway (7.2). The lowest ratios were recorded for the eastern European Member States of Slovakia, Romania, Poland, Slovenia and Hungary, each reporting averages of less than 1.0 air passenger carried per inhabitant in 2013.

Maritime passengers

Table 4 also shows that ports in the EU-28 handled almost 400 million maritime passengers in 2012, which was a reduction of 3.6 % compared with 2011. Indeed, from its pre-financial and economic crisis high of 439 million passengers in 2008, the number of maritime passengers carried in the EU-28 fell for four consecutive years, with passenger numbers down overall by 9.4 % between 2008 and 2012.

Italian and Greek ports each handled roughly twice as many maritime passengers in 2012 as in any other EU Member State, there 76.7 million and 72.8 million passengers accounting for 19.3 % and 18.3 % of the EU-28 total respectively. Denmark (41 million passengers) had the next highest number of maritime passengers, followed by Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Croatia, France (data are for 2012) and Spain, which each handled between 30 million and 23 million passengers in 2013.

Relative to national population, the importance of maritime passenger transport was particularly high in Malta (20.8 passengers per inhabitant in 2013), followed by Estonia (9.8), Denmark (7.3), Greece (6.6, data are for 2012) and Croatia (6.4); other than Finland, Sweden and Italy (2012), the number of maritime passengers per inhabitant in 2013 averaged less than 1.0 in each of the remaining EU Member States.

Data sources and availability

The majority of inland passenger transport statistics are based on vehicle movements in each of the reporting countries, regardless of the nationality of the vehicle or vessel involved (the ‘territoriality principle’). For this reason, the measure of passenger-kilometres (pkm, which represents one passenger travelling a distance of one kilometre) is generally considered as a more reliable measure, as a count of passengers entails a higher risk of double-counting, particularly for international transport. The methodology used across the EU Member States is not harmonised for road passenger transport.

The modal split of inland passenger transport identifies transportation by passenger car, bus and coach, and train; it generally concerns movements on the national territory, regardless of the nationality of the vehicle. The modal split of passenger transport is defined as the percentage share of each mode and is expressed in passenger-kilometres. For the purpose of this article, the aggregate for inland passenger transport excludes domestic air and water transport services (inland waterways and maritime).

The level of inland passenger transport (measured in passenger-kilometres) may also be expressed in relation to GDP; within this article the indicator is presented based on GDP in constant prices for the reference year 2000, with the series converted into an index with a base of 2000 = 100. This indicator provides information on the relationship between passenger demand and the size of the economy and allows the intensity of passenger transport demand to be monitored relative to economic developments.

Rail passengers

A rail passenger is any person, excluding members of the train crew, who makes a journey by rail. Rail passenger data are not available for Malta and Cyprus (or Iceland) as they do not have railways. Annual passenger statistics for national and international transport generally only cover larger rail transport enterprises, although some countries use detailed reporting for all railway operators.

Air passengers

Air transport statistics concern national and international transport, as measured by the number of passengers carried; information is collected for arrivals and departures. Air passengers carried relate to all passengers on a particular flight (with one flight number) counted once only and not repeatedly on each individual stage of that flight. Air passengers include all revenue and non-revenue passengers whose journeys begin or terminate at the reporting airport and transfer passengers joining or leaving a flight at the reporting airport; excluded are direct transit passengers. Air transport statistics are collected with a monthly, quarterly and annual frequency, although only the latter are presented in this article. Air transport passenger statistics also include the number of commercial passenger flights, as well as information relating to individual routes and the number of seats available. Annual data are available for most of the EU Member States from 2003 onwards.

Maritime passengers

Maritime transport data are generally available from 2001 onwards, although some EU Member States have provided data since 1997. Maritime transport statistics are not transmitted by the Czech Republic, Luxembourg, Hungary, Austria or Slovakia, as none of these has any maritime traffic.

A sea passenger is defined as any person that makes a sea journey on a merchant ship; service staff are not regarded as passengers, neither are non-fare paying crew members travelling but not assigned, while infants in arms are also excluded. Double-counting may arise when both the port of embarkation and the port of disembarkation report data; this is quite common for the maritime transport of passengers, which is generally a relatively short distance activity.

Context

EU transport policy seeks to ensure that passengers benefit from the same basic standards of treatment wherever they travel within the EU. Passengers already have a range of rights covering areas as diverse as: information about their journey; reservations and ticket prices; damages to their baggage; delays and cancellations; or difficulties encountered with package holidays. With this in mind the EU legislates to protect passenger rights across the different modes of transport:

- Regulation 261/2004 establishing ‘common rules on compensation and assistance to passengers in the event of denied boarding and of cancellation or long delays of flights’; in March 2013 the European Commission proposed a revision of this Regulation (COM(2013) 130 final) aiming to clarify grey areas, introduce new rights (for example concerning rescheduling), strengthen oversight of air carriers, and balance financial burdens;

- Regulation 1371/2007 on ‘rail passengers’ rights and obligations’;

- Regulation 181/2011 establishing ‘the rights of passengers in bus and coach transport’;

- Regulation 1177/2010 establishing ‘the rights of passengers when travelling by sea and inland waterway’.

Specific provisions have also been developed in order to ensure that passengers with reduced mobility are provided with necessary facilities and not refused carriage unfairly.

In December 2011, the European Commission adopted ‘A European vision for passengers: communication on passenger rights in all transport modes’ (COM(2011) 898 final). This acknowledged the work undertaken to introduce passenger protection measures to all modes of transport but notes that a full set of rights is not completely implemented. The Communication aims to consolidate the existing work, and move towards a more coherent, effective and harmonised application of rights alongside better understanding among passengers.

In March 2011, the European Commission adopted a White paper, the ‘Roadmap to a single European transport area — towards a competitive and resource efficient transport system’ (COM(2011) 144 final). This comprehensive strategy contains a roadmap of 40 specific initiatives for the next decade to build a competitive transport system that aims to increase mobility, remove major barriers in key areas and fuel growth and employment.

More details concerning the European Commission’s proposals for transport policy initiatives are provided in an introductory article on transport in the EU.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Energy, transport and environment indicators — 2014 edition

Main tables

- Transport, see:

- Transport, volume and modal split (t_tran_hv)

- Volume of passenger transport relative to GDP (tsdtr240)

- Modal split of passenger transport (tsdtr210)

- Railway transport (t_rail)

- Rail transport of passengers (ttr00015)

- Air transport (t_avia)

- Air transport of passengers (ttr00012)

Database

- Transport, see:

- Multimodal data(tran)

- Transport, volume and modal split (tran_hv)

- Volume of passenger transport relative to GDP (tran_hv_pstra)

- Modal split of passenger transport (tran_hv_psmod)

- Transport, volume and modal split (tran_hv)

- Railway transport (rail)

- Railway transport measurement - passengers (rail_pa)

- Road transport (road)

- Road transport measurement - passengers (road_pa)

- Maritime transport (mar)

- Maritime transport - passengers (mar_pa)

- Air transport (avia)

- Air transport measurement - passengers (avia_pa)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

Methodological notes

- Methodological notes on maritime transport statistics

ESMS metadata files

- Air transport infrastructure, transport equipment, enterprises, employment and accidents (ESMS metadata file — avia_if_esms)

- Maritime transport (ESMS metadata file — mar_esms)

- Modal split of passenger transport (ESMS metadata file — tran_hv_psmod_esms)

- Passenger and freight transport by air/Traffic data/Air transport at regional level (ESMS metadata file — avia_pa_esms)

- Railway transport measurement (ESMS metadata file — rail_pa_esms)

- Regional transport statistics (ESMS metadata file — reg_tran_esms)

- Volume of passenger transport relative to GDP (ESMS metadata file — tran_hv_frtra_esms)

Methodology manuals

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

Other information

External links

- Eurocontrol — The Single European Sky

- International Transport Forum — ITF (formerly the European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT))

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) — transport statistics