Archive:People in the EU - statistics on an ageing society

- Data extracted in June 2015. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles that are based on Eurostat’s flagship publication People in the EU: who are we and how do we live? (which also exists as a PDF publication); it presents a range of statistics that cover elderly persons living in the European Union (EU).

(years)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_hlye)

(% of total life expectancy)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_hlye)

(% of total population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind)

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (Census hub HC55)

(%, elderly population (aged 65 years and over) as a share of the working-age population (aged 15–64))

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (Census hub HC56)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (Census hub HC28)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (Census hub HC39)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (Census hub HC10)

(% of economically active population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (Census hub HC13)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (lfso_12reduchrs)

(years)

Source: Eurostat (lfso_12agepens)

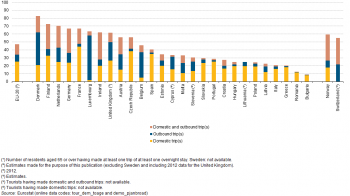

(% of persons aged 65 years and over)

Source: Eurostat (tour_dem_toage) and (demo_pjanbroad)

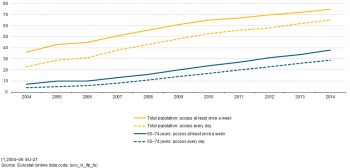

(%)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_ci_ifp_fu)

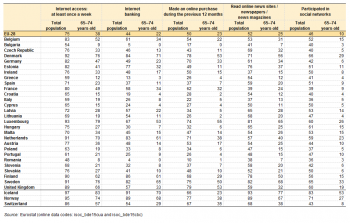

(%)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_bde15cua) and (isoc_bde15cbc)

Main statistical findings

Population ageing is one of the greatest social and economic challenges facing the EU. Projections foresee a growing number and share of elderly persons (aged 65 and over), with a particularly rapid increase in the number of very old persons (aged 85 and over). These demographic developments are likely to have a considerable impact on a wide range of policy areas: most directly with respect to the different health and care requirements of the elderly, but also with respect to labour markets, social security and pension systems, economic fortunes, as well as government finances.

EUROPEAN POLICIES RELATING TO HEALTH AND THE ELDERLY

The EU promotes active ageing and designated 2012 as the European year for active ageing and solidarity between generations. It highlighted the potential of older people, promoted their active participation in society and the economy, and aimed to convey a positive image of population ageing.

The innovation union is one of the Europe 2020 flagship initiatives. One of the European innovation partnerships concerns active and healthy ageing. Its aim is to tackle the challenges associated with an ageing population, setting a target of raising the healthy lifespan of EU citizens by two years by 2020. In 2012, the European Commission adopted a Communication on ‘Taking forward the strategic implementation plan of the European innovation partnership on active and healthy ageing’ (COM(2012) 83 final). The partnership aims to: enable older people to live longer, healthier and more independent lives; improve the sustainability and efficiency of health and care systems; and to create growth and market opportunities for business in relation to the ageing society.

The EU’s structural funds provide possibilities to support research, innovation and other measures for active and healthy ageing. Active ageing is an important area of social investment, as emphasised in the European Commission’s Communication ‘Towards social investment for growth and cohesion’ (COM(2013) 83 final) and is consequently one of the investment priorities of the European Social Fund (ESF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) during the 2014–20 programming period.

For those senior citizens who remain in good health, some will decide to continue at work or become active in voluntary work, while others may join a variety of social groups, return to education, develop new skills, or choose to use their free time for travelling or other activities. As life expectancy continues to rise, the constraints, perceptions and requirements of retirement are changing; many of these issues are explored within this article.

Healthy life years

Life expectancy has continued to rise systematically in all of the EU Member States in recent decades. Historically, the main reason for this was declining infant mortality rates, although once these were reduced to very low levels, the increases in life expectancy continued, largely as a result of declining mortality rates for older people, due for example to medical advances and medical care, as well as improved working and living conditions. Nevertheless, there are considerable differences in life expectancy both between and within Member States; more information is presented in an article on Demographic changes — profile of the population.

While it is broadly positive that life expectancy continues to rise and each person has a good chance of living longer, it is not so clear that additional years of life are welcome if characterised by a range of medical problems, disability, or mental illness. Indicators on healthy life years combine information on mortality with data on health status (disability). They provide an indication as to the number of remaining years that a person of a particular age can expect to live free from any form of disability, introducing the concept of quality of life into an analysis of longevity. These indicators can be used, among others, to monitor the progress being made in relation to the quality and sustainability of healthcare.

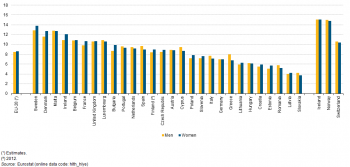

Women in the EU could expect to live 61.5 years free from any form of disability, just 0.1 years more than men

Eurostat statistics on mortality are based on the annual demographic data collection. They show that the average life expectancy of a girl born in 2012 in the EU-28 was 82.4 years, while the life expectancy of a boy was 76.8 years. While women had higher life expectancy than men in all of the EU Member States, there has been a pattern of convergence in recent years. In contrast to this upward development witnessed for life expectancy, there has been a slight fall in the number of healthy life years: Figure 1 shows that a girl born in 2013 could expect to live an average of 61.5 years in a healthy state free from any form of disability (which was a decline of 1.1 years when compared with the situation in 2010), while a boy could expect to live 61.4 years free from disability (a decline of 0.4 years when compared with 2010).

The elderly population of Sweden could expect to live longest free from any form of disability

At the age of 65, women in the EU-28 had a life expectancy of 21.1 years, while that for men was some 3.4 years less, at 17.7 years. There were considerable differences between the EU Member States as regards the number of healthy life years at 65 years of age (see Figure 2), while the differences between the sexes were far less pronounced. In 2013, women in the EU-28 aged 65 could expect to live an additional 8.6 years free from disability, which was 0.1 years higher than for men. Among the EU Member States, the range for women was from a high of 13.8 healthy life years in Sweden to a low of 3.7 years in Slovakia, while for men there was a high of 12.9 healthy life years (also in Sweden) and a low of 4.0 years in Latvia.

Elderly men in the southern EU Member States enjoyed a longer lifespan free from disability than elderly women

The largest gender gaps for individual EU Member States were recorded in Bulgaria and Ireland where women at the age of 65 could expect to enjoy an additional 1.2 years of life free from disability (compared with men); there were 13 other Member States where women registered a higher number of healthy life years. In Germany, there was no difference at age 65 in the number of healthy life years between the sexes. By contrast, men could expect to live longer free from disability in 12 of the Member States, with the largest gender gaps in favour of men recorded in some of the southern EU Member States: Italy (0.6 years), Spain (0.7 years), Cyprus (0.8 years) and Greece (1.2 years).

Figure 3 combines the information on life expectancy and healthy life years to show what proportion of their remaining lives people aged 65 could expect to live free from disability. Across the whole of the EU-28, on average, a man could expect to live almost half (47.7 %) of his remaining life free from disability, while the corresponding share for a woman was around two fifths (40.1 %). There were seven EU Member States where women aged 65 could expect to live more than half of their remaining lives free from disability, they were: Sweden, Denmark, Malta, Ireland, Bulgaria, the United Kingdom and Belgium. In the same seven Member States, men aged 65 could also expect to live more than half of their remaining lives free from disability, while this was also the case in seven more Member States. In all 28 EU Member States, men could expect to live a higher proportion of their remaining lives free from disability than could women; the biggest differences between the sexes were again recorded in some of the southern EU Member States: Spain, Greece, Portugal and Cyprus.

Elderly population structure and dependency rates

Did you know?

The highest number of elderly persons living in the EU (among NUTS level 3 regions) was recorded in the Spanish capital of Madrid, where 989 thousand persons aged 65 and over were resident in 2011. The second highest number was also recorded in Spain, as there were 949 thousand elderly persons resident in Barcelona. The third highest value was recorded in the Italian capital of Roma (809 thousand elderly residents).

For more information: refer to the CENSUS HUB

Structural changes to the demographics of the EU-28’s population may be largely attributed to the consequences of persistently low birth rates and increasing life expectancy. Eurostat’s annual demography data collection shows there were 506.8 million people living in the EU-28 in 2014, of whom almost 94 million were aged 65 years and over. Furthermore, 57.5 % of the elderly were women.

The elderly accounted for more than one fifth of the population in Italy, Germany and Greece

The proportion of elderly persons in the population differs greatly from one EU Member State to another. In 2014, it peaked at 21.4 % in Italy, 20.8 % in Germany and 20.5 % in Greece. The elderly generally accounted for 17–20 % of the total population in the remaining Member States, although Romania, Poland, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Slovakia and Ireland were below this range; the lowest share of the elderly was recorded in Ireland (12.6 %).

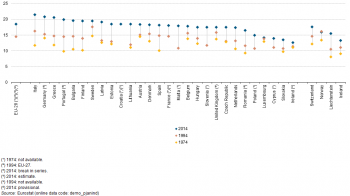

Figure 4 shows that the speed of population ageing varies considerably between the EU Member States. Among the 22 Member States for which data are available, the pace of demographic change between 1974 and 2014 was most pronounced in Portugal, Italy, Finland, Bulgaria, Greece and Spain, while the pace of change was relatively slow in Belgium, Austria, the United Kingdom, Slovakia, Ireland and Luxembourg. Some of these differences may be explained by variations in fertility rates.

The elderly often accounted for a high share of the population in rural regions

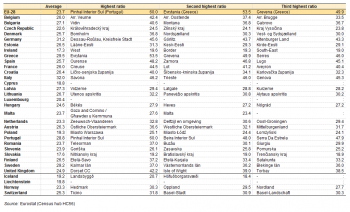

Information from the population and housing census provides a more detailed analysis of population structures for NUTS level 3 regions. Table 1 shows those regions with the highest shares of elderly persons in 2011. Across the whole of the EU-28, the three highest shares were recorded in the interior Portuguese region of Pinhal Interior Sul (33.6 %), the central Greek region of Evrytania (31.0 %) and the north-western Spanish region of Ourense (29.4 %).

The majority of the regions with high shares of elderly persons were in rural and sometimes quite remote regions, although this pattern was reversed in some of the eastern EU Member States, most notably in Poland, where the highest shares of the elderly were recorded in the cities of Warszawa and Łódź.

Table 2 provides similar information (also taken from the population and housing census), but focuses on the relationship between the number of elderly persons and those of working-age, otherwise referred to as the old-age dependency ratio. In 2011, those aged 65 and over were equivalent in number to 60.0 % of the working-age population in Pinhal Interior Sul and to more than half (53.5 %) of the working-age population in Evrytania. These were the only two regions where there were fewer than two persons of working age for each elderly person. The third highest old-age dependency ratio was recorded in the northern Greek region of Grevena (49.9 %).

Elderly population by place of birth

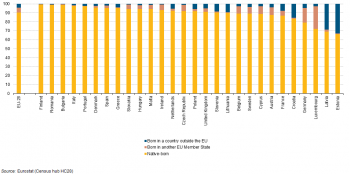

According to the results of the population and housing census conducted in 2011, more than 9 out of 10 (90.4 %) elderly persons in the EU-28 were resident in their country of birth, while 5.5 % were born in another EU Member State and 4.1 % were born in countries outside of the EU.

Did you know?

In 2011, the highest number of foreign-born elderly persons living in any of the NUTS level 3 regions within the EU was recorded in the southern French region of the Bouches-du-Rhône (which includes the city of Marseille), with just over 74 thousand foreign-born residents aged 65 and over.

The highest proportion of foreign-born elderly persons was recorded in the eastern Estonian region of Kirde-Eesti, where almost three quarters (74.6 %) of the population aged 65 and over had been born abroad.

For more information: refer to the CENSUS HUB

There were 1.6 million elderly persons born in Poland who were resident in Germany

There were 10 EU Member States where in excess of 1 in 10 elderly persons were foreign-born, from either another EU Member State or a country outside the EU. In Belgium, Sweden, Cyprus and Austria, the proportion of foreign-born elderly persons ranged from 11–13 %, with the elderly born in another EU Member State outnumbering those born in countries outside of the EU. Foreign-born residents accounted for a slightly higher share of the elderly populations of France and Croatia, and in both cases, there were more foreign-born residents from countries outside the EU. In Germany and Luxembourg, the foreign-born population accounted for more than one in five of the elderly population. A high proportion of the foreign-born residents living in Germany were born in Poland (1.6 million people aged 65 and over). This equated to two thirds of the foreign-born elderly residents from other EU Member States who were living in Germany, or to 10.3 % of the total elderly population in Germany. Foreign-born residents accounted for an even higher share of the elderly populations of Latvia and Estonia, around one third of the total (31.1 % and 33.9 % respectively). The vast majority of the foreign-born residents in these two Baltic Member States came from outside the EU, principally from Russia.

Senior citizens on the move

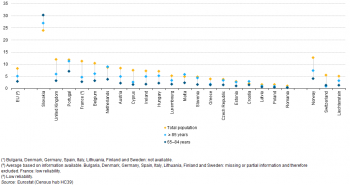

Figure 6 shows the proportion of 65–84 year-olds in the EU who moved during the 12-month period prior to the population and housing census in 2011. Some 2.9 % of the elderly changed residence, which was considerably lower than the average for the whole population (8.3 %); note these figures cover only 20 of the EU Member States as data for Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Spain, Italy, Lithuania, Finland and Sweden are either partially available or not available.

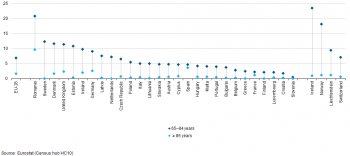

Elderly persons aged 85 and over were more likely to move than those aged 65–84

There was a higher propensity for people aged 85 or over to change accommodation: in the 12-month period prior to the census some 5.0 % of those aged 85 and over in the EU moved home. This may reflect an increasing proportion of the elderly persons moving to live with their relatives or moving into retirement homes or other forms of specialist accommodation.

Many people dream of retiring to another country, especially to a location near the sea and / or in southern Europe. According to results from the population and housing census, the reality is somewhat different as a relatively small number of people move abroad during their retirement. In 2011, two thirds (66.6 %) of the elderly persons in the EU aged 65 and over who changed residence during the 12-month period prior to the census moved within the same NUTS level 3 region, while just over one quarter (28.4 %) moved from another region in the same EU Member State, and 5.1 % moved from outside the reporting country. Nevertheless, there were some destinations that appeared quite popular, as more than one quarter (27.9 %) of the elderly persons in Greece who had moved and around one fifth of the elderly persons in Cyprus, Luxembourg, Croatia and Malta who had moved, had done so from abroad (from other EU Member States or from countries outside the EU).

The elderly living alone

According to EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), some 13.4% of households in the EU-28 in 2013 were composed of a single person aged 65 or over. This share ranged from highs of 18.6 % in Romania and 17.7 % in Lithuania down to lows of 9.9 % in Spain and 7.4 % in Cyprus.

Did you know?

In 2011, the highest proportion of elderly persons living alone in the EU-28 was recorded in the Danish capital region of Hovedstaden (42.4 %).

For more information: refer to the CENSUS HUB

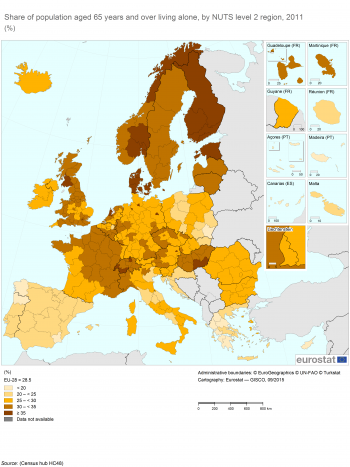

The elderly were more likely to be living alone in urban areas

The population and housing census allows a more detailed analysis: Map 1 shows that 28.5 % of the EU-28 population aged 65 and over were living alone in 2011. This share rose as high as 42.4 % in the Danish capital region of Hovedstaden, while the capital regions of Belgium, the United Kingdom and Finland followed with the next highest shares. As such, while a higher proportion of the elderly population lived in rural regions, those who were in urban regions were more likely to be living alone.

At the other end of the range, fewer than 20 % of the population aged 65 and over were living alone in several Greek, Spanish and Portuguese regions, as well as in Cyprus (a single region at this level of analysis) and the south-eastern Polish region of Podkarpackie; most of these regions were principally rural areas. The lowest share of the elderly living alone — among the NUTS level 2 regions — was recorded in the north-western Spanish region of Galicia (16.8 %).

Almost half of all women aged 85 and over were living alone

Women’s longer life expectancy has consequences in relation to the gender gap for elderly persons living alone. According to the population and housing census, there were almost 2.0 million elderly women living alone in the EU-28 in 2011, which equated to more than one third (36.9 %) of all women aged 65 and over. For comparison, just over one sixth (16.9 %) of all men aged 65 and over were living alone. Among those aged 85 and over, the share of the population living alone was considerably higher, reaching 49.5 % for women and 27.8 % for men.

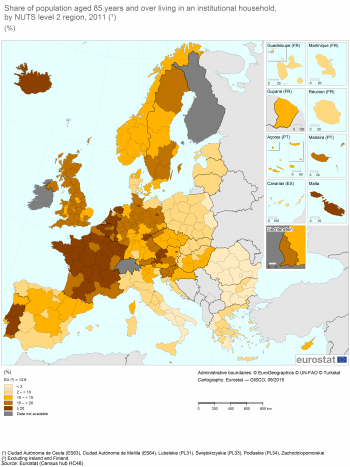

Most elderly people who lived in institutional households were aged 85 and over

Contrary to most social surveys, where data collection is usually restricted to private households, the population and housing census may be used to complement analyses of the elderly as it provides a more extensive set of results including information on those persons living in institutional households.

Most elderly people value their independence and would prefer to continue to live in their own homes. In 2011, the proportion of elderly persons in the EU who were aged 65–84 years and living in an institutional household (health care institutions or institutions for retired or elderly persons) was 1.7 %; note there is no information available for Ireland or Finland. Among those aged 85 and over, the share was more than seven times as high, reaching 12.6 % (see Map 2). The proportion of very old women living in an institutional household (14.8 %) was considerably higher than the corresponding share among very old men (7.6 %).

In absolute terms there was almost no difference in the number of people living in an institutional household in the EU in 2011: there were 1.35 million persons aged 85 and over, marginally higher than the 1.34 million aged 65–84 years-old.

In Luxembourg, almost one third of those aged 85 and over were resident in an institutional household

Among NUTS level 2 regions, the highest share of very old persons living in institutional households in 2011 was recorded in Luxembourg (a single region at this level of analysis), almost one third (32.9 %) of the population aged 85 and over. There were four regions across the EU where shares of 25–30 % were recorded, these included the French regions of Pays de la Loire and Bretagne, the Dutch region of Groningen, and Malta (also a single region at this level of analysis).

By contrast, a small proportion of those aged 85 and over in Bulgaria, Romania, southern Italy and parts of Greece were living in institutional households. For example, in the three Romanian regions of Sud-Est, Sud-Vest Oltenia and Sud - Muntenia the share of very old persons living in institutional households was no more than 1.0 % (the three lowest regional shares in the EU).

Economically active senior citizens

During the coming years, there are likely to be considerable changes in the demographic profile of the EU’s labour force. Activity rates among those aged 55–64 increased during the last decade and their growth was unabated during the financial and economic crisis. In the future most commentators expect these patterns to continue, with a growing proportion of the elderly remaining in work for longer, in part due to increases in retirement or pension ages and restrictions on taking early retirement, as well as some people wanting to carry on working and others feeling forced to work for economic reasons.

Nevertheless, beyond the age of 65, the share of the population that remains economically active declines sharply. The population and housing census conducted in 2011 shows there were 5.5 million persons aged 65 and over in the EU-28 who were economically active (employed or unemployed). The activity rate for those aged 65–84 was 6.8 %, while that for the very old (85 years and over) was 1.6 %.

Just over 20 % of those aged 65–84 in Romania remained economically active

In 2011, activity rates among the elderly were generally at their highest in several northern and western EU Member States; Sweden, Denmark, the United Kingdom and Estonia all reported activity rates of more than 10 % for the elderly population aged 65–84 (see Figure 7). However, the highest activity rate was recorded in Romania, where more than one fifth (20.8 %) of the elderly population remained economically active, a share that was almost twice as high as in Sweden (12.3 %). Among those aged 85 years and over, the activity rate in Romania was also by far the highest among the EU Member States, at 9.6 %; this was almost three times as high as the second highest rate, 3.6 % in Spain. One reason for these comparatively high activity rates in Romania may be the relatively large share of the population who continue to work in family-run agricultural holdings, of which there are many in Romania.

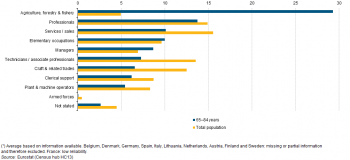

A relatively high proportion of elderly managers, labourers and farm workers remained economically active

The results from the population and housing census also allow an analysis of employment patterns according to occupation. In 2011, almost one third (29.3 %) of the elderly aged 65–84 who remained active had an agricultural, forestry or fishing-related occupation; note that this EU average excludes Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Spain, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland and Sweden (as there are no data available for each of these EU Member States). The share of elderly active persons with an agricultural, forestry or fishing-related occupation was almost six times as high as the average, as 5.0 % of the total population had agricultural, forestry or fishing-related occupations. There were only two other occupations — as shown in Figure 8 — where the proportion of the elderly active population was higher than the average for the whole population, as 10.0 % of the active elderly population had elementary occupations (compared with a 9.6 % share for the whole population) and 8.7 % of the active elderly population were managers (compared with 6.9 %); in the latter case this may reflect older people continuing to work in a managerial role in family-run businesses.

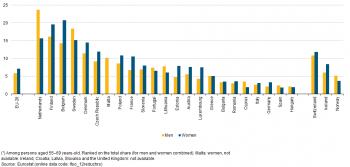

Slightly more than one in five persons in the Netherlands prepared for retirement by reducing their working hours

There are a range of determinants which may impact on decisions linked to older workers’ withdrawal from economic activity, including their income and savings, health, working conditions, and relations with other family members; all of these may play a role when taking decisions linked to transitions into retirement. It is important to note that retirement from paid work does not necessarily imply withdrawal from all types of activity, as an increasing proportion of elderly persons undertake unpaid care activities or are volunteers. Nevertheless, the activity rates and analysis of employment presented here are generally restricted to paid work (as an employee, employer or self-employed person) or as an unpaid family worker within a business (where payment is indirect through the benefits accruing to the business).

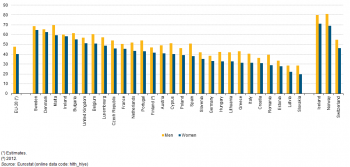

Figure 9 is based on data that has been taken from an ad-hoc module that formed part of the EU’s labour force survey (EU-LFS) in 2012; it shows information relating to the share of elderly persons who reduced their working hours as they approached retirement. In 2012, some 7.1 % of the women aged 55–69 surveyed across the EU-28 stated that they had reduced their hours as they approached retirement; this share was somewhat higher than that recorded among men (5.9 %). This pattern was repeated in most of the EU Member States, as the Netherlands, Sweden, Lithuania, Cyprus, Portugal, Spain and Hungary were the only exceptions to report that a higher proportion of men (than women) reduced their working hours.

There were considerable differences between the EU Member States as regards the share of the population (men and women) who reduced their working hours. In the Netherlands, slightly more than one in five persons (20.5 %) reduced their working hours, while double-digit shares were also recorded in Belgium, the Nordic Member States, the Czech Republic and Malta. By contrast, shares of less than 3.0 % were recorded in Cyprus, Italy, Germany, Spain and Hungary.

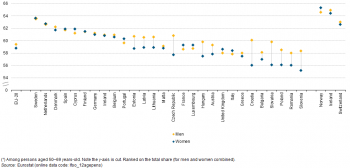

The EU-LFS ad-hoc module for 2012 also collected information in relation to the average age at which an old-age pension was first received. On average, in the EU-28 this was 59.4 years for men and 58.8 years for women; these figures refer to the results of a survey conducted among persons aged 50–69. This gender pattern was repeated in the majority of EU Member States, as France, Cyprus, Portugal, Italy, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Spain and Finland were the only exceptions to report a lower average age for men — in each case the gender gap was no more than 0.7 years.

Figure 10 shows that there was little difference between the sexes in relation to the average age for first receiving an old-age pension for those EU Member States that had the highest average ages. For example, the highest values were reported for Sweden and the Netherlands and there was no difference between the sexes for either of these Member States. By contrast, as the average age for first receiving an old-age pension fell the gaps between the sexes tended to increase. Women were more likely to first receive an old-age pension at a younger age than men in all of the eastern EU Member States and the Baltic Member States. This pattern was most apparent in Croatia, where women received a pension, on average, 4.1 years before men and was repeated in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Poland and Hungary (where women first received an old-age pension at least 2.3 years before men).

Elderly tourists

Travelling around the world is something that many people from all generations enjoy doing. Indeed, many older people take great pleasure from having more spare time in their retirement to be able to travel around their own country, other EU Member States or to destinations that are further afield.

Despite the elderly having more free time to travel, according to Eurostat’s tourism statistics, just under half (47.1 %) of the EU’s population aged 65 and over participated in tourism in 2013 (see Figure 11), compared with a 60.0 % share for the population aged 15 years and over.

As with other age groups, the possibilities for enjoying travel and tourism in older age are linked to the availability of income (financial reasons). However, among the elderly the issue of healthy life expectancy is of particular importance: indeed, the propensity for older people to travel diminishes with age. Indeed, health issues played a slightly greater role than financial issues in determining whether or not the EU’s elderly population participated in tourism, while a relatively high proportion of the elderly had no motivation to travel / go on holiday.

More than four out of every five elderly persons in Denmark went on holiday in 2013

In Denmark, more than four out of every five elderly persons participated in tourism in 2013: approximately one quarter of these went only on domestic trips, one quarter only on foreign trips and around one half on trips for domestic and foreign holidays. There were also relatively high shares — above 60 % — of the elderly participating in tourism in Finland, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Luxembourg, Ireland and the United Kingdom (data are for 2012).

By contrast, the share of the elderly population that participated in tourism was generally much lower among most of the southern and eastern EU Member States, as well as the Baltic Member States. Around one in five elderly persons in Italy and Greece made at least one overnight trip in 2013 (principally within their own countries). This share was even lower in Romania (11.9 %) and Bulgaria (9.0 %).

In relative terms, a lower proportion of the elderly population participated in tourism than the share recorded for those aged 15 years and over; This pattern held across all of the EU Member States for which data are available (no data for Sweden; data for the United Kingdom refer to 2012). In Denmark, the United Kingdom and France, the elderly were almost as likely to go on holiday as the average person. By contrast, in Italy, Slovenia, Romania, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Bulgaria, the proportion of the elderly who participated in tourism in 2013 was less than half the average recorded for the population aged 15 years and over.

Senior citizens online — silver surfers

Some senior citizens remain somewhat wary of technology and in particular computers and the internet. That said, a growing proportion of the elderly go online, either as younger generations who have used the internet move into the older age classes, or as people develop internet skills in their old age. Indeed, the internet opens up a wealth of new opportunities and services that may be of particular interest to the elderly.

More than one third of the elderly aged 65–74 used the internet at least once a week

Eurostat’s statistics on information and communication technologies (ICTs) show that in 2014 more than one third (38 %) of the elderly population — defined here as those aged 65–74 — in the EU-28 used the internet on a regular basis, in other words at least once a week. This figure could be compared with the situation a decade earlier, when just 7 % of the elderly population was using the internet at least once a week.

Figure 12 also provides information on the share of the elderly population who made daily use of the internet. These statistics show that, once the elderly are confident enough to use technology, they start using the internet actively, just like younger generations. While 57 % of the elderly who used the internet at least once a week in 2004 did so on a daily basis, this share had risen to 76 % in 2014.

More than one fifth of the elderly used the internet for online banking

Table 3 shows that across the whole of the EU-28, just over one fifth (22 %) of the elderly persons aged 65–74 made use of internet banking in 2014; this was half the share recorded for the total population (44 %). A similar share of the elderly used the internet for making online purchases (23 %) and for reading news sites or online newspapers (25 %). By contrast, relatively few elderly persons participated in social networks on the internet (10 %, compared with 46 % of the total population).

In relation to their regular use of the internet, there is a relatively large digital divide between northern and western EU Member States on one hand and southern and eastern EU Member States on the other. Luxembourg (79 %), Denmark (76 %), Sweden (76 %), the Netherlands (70 %), the United Kingdom (66 %), Finland (62 %) and Belgium (52 %) were the only EU Member States where more than half of the elderly population aged 65–74 used the internet in 2014 at least once a week. In Romania and Bulgaria, on the other hand, less than 10 % of all senior citizens aged 65–74 went online at least once a week, a share that rose to 12 % in Greece and 15 % in Croatia and Cyprus.

See also

- All articles from People in the EU: who are we and how do we live?

Further Eurostat information

Main tables

- Population (t_demo_pop)

- Fertility (t_demo_fer)

- Mortality (t_demo_mor)

- International Migration (t_migr_int)

- Marriage and divorce (t_demo_nup)

- Population projections (t_proj)

Database

- Population (demo_pop)

- Mortality (demo_mor)

- Population projections (proj)

- Population and housing census (cens)

Dedicated section

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

Other information

- EU legislation on the 2011 Population and Housing Censuses — Explanatory Notes

- Legislation relevant for the population and housing census

- Demographic statistics: a review of definitions and methods of collection in 44 European countries

- Legislation relevant for population statistics

External links

- European Commission — Directorate-General for health and food safety — Ageing

- European Commission — annual ageing report

- European Commission — population ageing in Europe