Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - education

- Data from October 2014. Most recent data:Further Eurostat information, Main tables.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on the Eurostat publication Smarter, greener, more inclusive? - Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy. It provides recent statistics on education in the European Union (EU), a key area of the EU's Europe 2020 strategy.

The analysis builds on the headline indicators chosen to monitor the Europe 2020 strategy's education targets: 'early leavers from education and training' and 'tertiary educational attainment'.

The analysis follows the typical educational pathway, starting with early childhood education, followed by acquisition of basic skills (reading, maths and science) and foreign languages, leading to tertiary education and life-long learning in adulthood; it then switches to the ‘outcome’ side, looking at educational attainment in the EU labour force and the impacts of low levels of attainment; finally, the input in the form of public expenditure on education, is investigated.

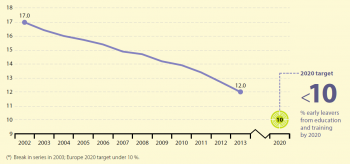

Europe 2020 strategy target on education The Europe 2020 strategy sets out a target of ‘reducing school drop-out rates to less than 10 % and increasing the share of the population aged 30 to 34 having completed tertiary or equivalent education to at least 40 %’ by 2020 [1].

(% of population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_40)

(% of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_40)

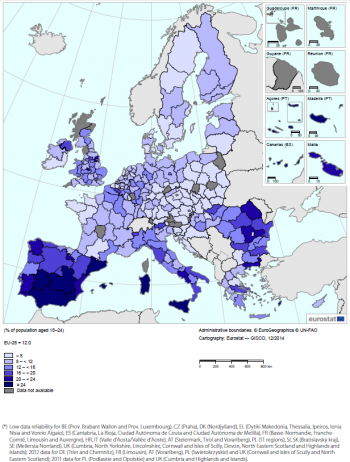

(% of population aged 18 to 24)

(edat_lfse_16)

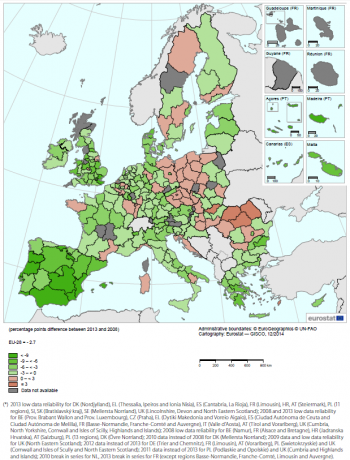

(percentage points difference between 2013 and 2008, population aged 18 to 24)

(edat_lfse_16)

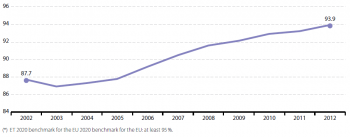

(% of the age group between 4 years old and the starting age of compulsory education)

Source: Eurostat online data code (tps00179)

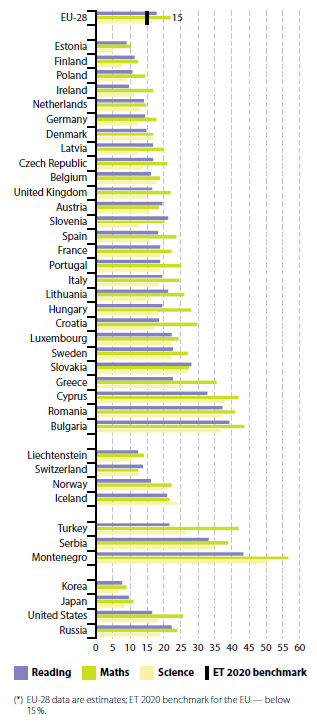

(share of 15-year-old pupils who are below proficiency level 2 on the PISA scales for reading, maths and science)

Source:OECD/PISA, Eurostat online data code (t2020_30)

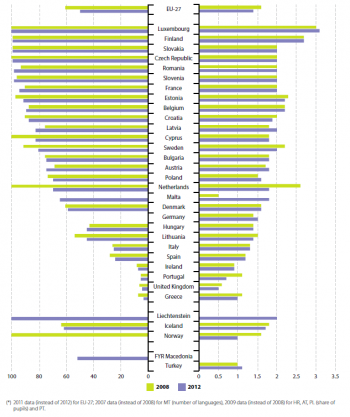

(% of pupils at ISCED level 3 general learning two or more foreign languages (left); average number of foreign languages learned per pupil at ISCED level 3 general (right))

Source: Eurostat online data code (educ_thfrlan)

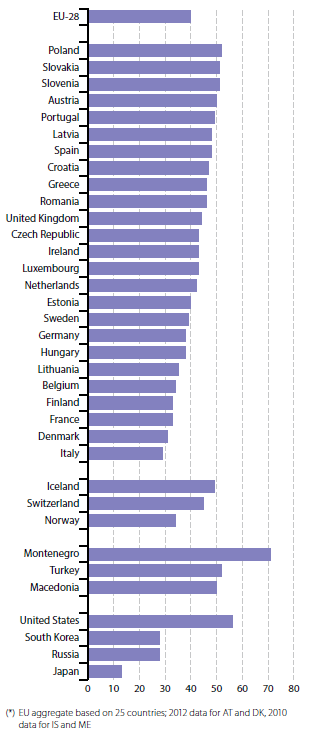

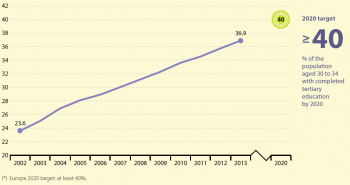

(% of the population aged 30 to 34 with completed tertiary education (ISCED levels 5 and 6))

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41)

(% of the population aged 30 to 34 with completed tertiary education (ISCED levels 5 and 6))

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41)

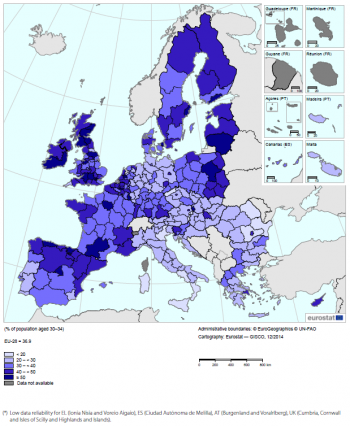

(% of the population aged 30 to 34 with completed tertiary education (ISCED levels 5 and 6))

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41), Statistics Austria, Destatis

(% of population aged 30 to 34)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_12)

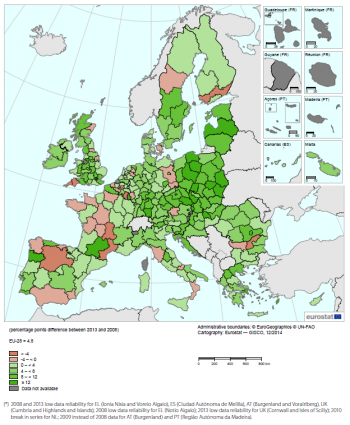

(percentage points difference between 2013 and 2008, population aged 30 to 34)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_12)

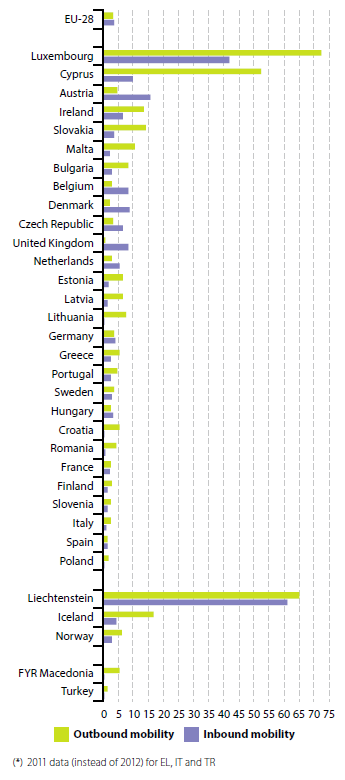

(outbound: students (ISCED 5–6) studying in another EU-28, EEA or candidate country as % of all students; inbound: inflow of students (ISCED 5–6) from EU-28, EEA and candidate countries as % of all students in the country)

Source: Eurostat online data code (educ_thomb)

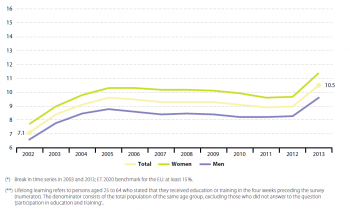

(% of population aged 25 to 64) (**)

Source: Eurostat online data code (tsdsc440)

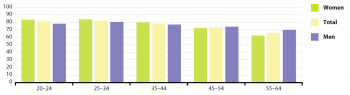

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_08)

(% of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_14)

(% of population aged 18 to 24)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_20)

(share of employed graduates (20 to 34 years old) having left education and training in the past one to three years)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_24)

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat online data code (educ_figdp)

Main statistical findings

Early leaving from education and training is declining

The headline indicator ‘Early leavers from education and training’ shows the share of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and not in further education or training. This indicator refers to both people who failed and dropped out of school and those who did not fail but left education without continuing. Figure 2 indicates that since 2002 the share of early leavers from education and training has fallen continuously in the EU. This trend mirrors reductions in almost all EU Member States for both men and women.

Young men, foreign-born and ethnic minorities leave education and training earlier

In the EU as a whole, rates of early leaving from education and training are about three percentage points higher for men than for women. Since 2002, this gap has closed only slightly. Bulgaria and Czech Republic were the only EU Member States in 2013 where men were more likely to stay in education and training. A similar situation could be observed in the candidate countries Turkey and FYR Macedonia [2]. In all other EU Member States men were more likely to leave education earlier. Gender differences were particularly strong in Cyprus, Estonia, Spain, Latvia, Portugal and Italy. In these countries, early leaving was twice as high or more for men than for women.

Similarly, young foreign-born residents have a higher tendency to abandon formal education prematurely. In the EU, the share of early leavers among migrants in 2013 was more than twice as high as for natives (22.6 % compared with 11 %). Language difficulties, leading to underachievement and lack of motivation, are possible reasons. Lower socioeconomic status of foreign-born residents increasing the risk of social exclusion is another [3]. Educational systems may also exacerbate these circumstances if they are not set up to respond to the special needs of pupils from vulnerable groups [4].

In a number of Member States the proportion of pupils dropping out early or even not attending school at all is especially high among ethnic minority groups, such as Roma. In 2011 more than 10 % of Roma children were not attending compulsory education in Romania, Bulgaria, France and Italy. This figure reached 35 % in Greece [5].

Ethnic minorities are likely to be excluded from education due to a combination of factors including parental choices, poverty, discriminatory practices, residential segregation and language barriers [6]. In response to persistent marginalisation and social exclusion of Roma minorities, the European Commission in 2011 adopted the ‘EU Framework for national Roma integration strategies up to 2020’ [7]. The framework reflects the EU’s commitment to ensuring Roma inclusion in four key areas, including access to education.

Early leaving from education and training is highest in Southern Europe

Reflecting different national circumstances, the common EU target for early leavers from education and training has been transposed into national targets by all Member States except the United King-dom [8]. National targets range from 4 % for Croatia to 16 % for Italy. In 2013, 10 countries had already achieved their targets: Austria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Sweden and Slovenia. On the other end of the scale, Portugal and Malta were the furthest away by some 10 percentage points.

In 2013, rates of early leaving varied by a factor of six across EU Member States. The lowest proportion of early leavers was in Croatia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic and Poland with less than 6 %. The share was highest in Spain, Malta, Portugal, Romania and Italy, with 17 % or more.

At the same time Southern European countries experienced strong falls in early leaving from education and training over the period 2008 to 2013, especially Portugal (from 34.9 % to 18.9 %), Spain (from 31.7 % to 23.6 %) Malta (from 27.2 % to 20.8 %), Greece (from 14.4 % to 10.1 %) and Cyprus (from 13.7 % to 9.1 %). In 2013, 21 EU Member States showed early leaving rates below the EU average of 12 % and 18 were already below the overall EU target of 10 %.

Looking at the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and candidate countries, Switzerland was on a level with the best performing EU Member States. However, the share of early leavers was above the EU average in Norway, Iceland and up to three times the EU average in Turkey.

The variations in the incidence of early leaving from education and training across Member States are also mirrored in the indicator’s regional dispersion (see Map 1). The predominance of regions with a very low share of early leavers (below 8 %) that can be seen in some Central and Eastern European countries, such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia and Croatia, corresponds to the overall low proportion of early leavers in these countries.

In stark contrast, regions in Spain, Portugal, Italy and Romania stand out with above average rates of early leavers from education and training. The autonomous cities and islands of Spain and Portugal recorded the highest proportions of 18 to 24 years olds who were classified as early leavers in 2013 (27 % and above). The share of early leavers was also higher than 20 % in three regions from the extremities of Italy (including the islands of Sardegna and Sicilia), the far north-eastern Greek region of Anatoliki Makedonia and the Greek island group of Notio Aigaio. Outside southern Europe, more than one fifth of the population aged 18 to 24 was composed of early leavers from education and training in five largely rural, sparsely populated regions in the United Kingdom (two of which were at the outer limits of the territory — Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland), as well as in two Romanian regions.

In 2013, Poland, the United Kingdom and Bulgaria showed the biggest within-country dispersion of early leaving rates, with a factor higher than four. This means that the worst performing regions in these countries had early leaving rates that were about four times the rates of the best performing regions. In 2013, the Polish region Warminsko-Mazurskie had early leaving rates 4.5 times higher than the best performing regions in Poland. In contrast, Slovenia, Croatia and Finland were the most ‘equal’ countries, showing almost no difference in rates across their regions.

Map 2 shows the change in regional rates of early leaving from education and training since 2008. More than three quarters (78.6 %) of the 295 NUTS 2 regions for which data are available have experienced a fall in their proportion of early leavers aged 18 to 24 during the five consecutive years from 2008 to 2013. The biggest reductions were recorded in Portuguese and Spanish regions. The largest decline was in the Norte region of Portugal, where the proportion of early leavers fell by 19.9 percentage points.

In contrast, early leaving rates increased in 63 regions over the period from 2008 to 2013. The largest rise was in the Highlands and Islands and Cumbria in the United Kingdom, where the proportion of early leavers rose by 13.7 and nine percentage points respectively. Four other regions had increases of more than four percentage points; two of which were located in Romania, one was in the Netherlands and the remaining one was in Hungary.

Starting early

Early childhood education and care is improving

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) can bring wide-ranging social and economic benefits for individuals and for society as a whole. Quality ECEC provides an essential foundation for effective lifelong learning and future educational achievements. It also helps personal development and social integration. The European Union therefore aims to ensure that all young children can access and benefit from high-quality education and care [9].

Participation in ECEC is considered a crucial factor for socialising children into formal education. This is especially important for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. The aim is to reduce the incidence of early school leaving, addressing one of the Europe 2020 headline targets on education. Investment in pre-primary education also offers higher medium- and long-term returns and is more likely to help children from low socio¬economic status than investments at later educational stages [10].

ET 2020 recognises ECEC’s potential for addressing social inclusion and economic challenges. It has set a benchmark to ensure that at least 95 % of children aged between four and the starting age of compulsory education participate in ECEC. As Figure 4 shows, participation has risen more or less continuously in the EU since 2002. Several countries had already exceeded the ET 2020 benchmark in 2012, implying almost universal pre-school attendance. France and Malta had already achieved a 100 % pre-school attendance, and in Italy, the Netherlands and Ireland participation rates were above 99 %. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the lowest pre-school attendances were observed in Croatia (71.7 %), Finland (75.1 %) and Greece (75.2 %).

Integrating foreign-born population and ethnic minorities in early childhood education remains a challenge

Gender differences in early childhood education are negligible across the EU. However, children with a migrant background or from ethnic minorities are in a very disadvantaged position. For example, a recent study of 11 Member States revealed a large gap between Roma and non-Roma children attending pre-school and kindergarten in nine of the countries [11]. The EU has since identified accessibility to early childhood education and care for children from ethnic minorities a priority area within the ECEC participation framework. This reflects the growing consensus at policy level that early pre-schooling has an important role to play in addressing disadvantages and reducing the risk of poverty and social exclusion [12].

Acquiring the relevant skills for the knowledge society

A key objective of all educational systems is to equip people with a wide range of skills and competences. This encompasses not only basic skills such as reading and mathematics, but also more transversal ones such as information and communication technology (ICT) and entrepreneurship.

Basic skills: poor reading, maths and science affect one-fifth of EU pupils

Basic skills, whether reading simple text or performing easy calculations, provide the foundations for learning, gaining specialised skills and personal development. The ET 2020 framework acknowledges the increasing importance of individual skills in the era of the knowledge-based economy. In response, it has set a target to reduce the share of 15 year olds achieving low levels of reading, mathematics and science to less than 15 % by 2020.

In 2012, about one-sixth to almost one-fourth of 15 year old EU citizens showed insufficient abilities in reading, mathematics and science as measured by the OECD’s PISA study [13]. The test results were best for science, with 16.6 % low achievers, followed by reading with 17.8 % and maths with 22.1 %. Figure 5 shows how the overall performance in reading, mathematics and science varied significantly across countries. The share of pupils failing to acquire competences in the key subjects surpassed 38 % in Bulgaria and Romania. However, Northern Europe, in particular Finland, Estonia and the Netherlands, as well as Poland showed the lowest share of low achievers in reading, mathematics and science with levels below 15 %.

Compared with international competitors, the overall EU’s share of low-achievers in reading, maths and science was similar to that of the United States. However, it was higher than for Japan or Korea, where the shares of low-achieving pupils in 2012 were below 12 % and 10 % respectively.

Achievement in science has shown the most progress at the EU level since 2000, while progress in mathematical competences has been the slowest. For the EU as a whole, the ET 2020 benchmark implies that the share of low achievers needs to be reduced by a tenth (for science) up to almost a third (for maths) compared with 2012 levels.

When looking at gender, a large gap in reading performance can be seen. In 2012, the share of low achieving OECD pupils was about twice as high among boys (23.6 %) than among girls (11.7 %). This means girls have already reached the ET 2020 framework’s 15 % reading benchmark, implying effort needs to be focused on boys to balance performance levels. Gender differences are considerably smaller in the other key subject areas. Boys slightly outperform girls in maths and girls slightly outperform boys in science.

Wide variations in foreign language learning across Member States

The ability of citizens to communicate in at least two languages besides their mother tongue has been identified as a key priority in the EU’s ET 2020 framework. The European Commission has proposed monitoring student proficiency in the first foreign language and the uptake of a second foreign language at lower secondary level. Member States must ensure that the quantity and quality of foreign language education is scrutinised and that teaching and learning is geared towards practical, real-life application. Foreign language skills should be taken into account in the effort to equip young people with the competences needed to meet labour market demands. This aim is reflected in the recent Communication on youth unemployment and a number of 2013 country-specific recommendations [14].

Figure 6 shows that in 2012 the study of a second foreign language in general upper secondary education (ISCED level 3 general) was almost universal in Luxembourg, Finland and most Eastern European countries. It was much less popular in English-speaking countries (United Kingdom and Ireland) and in Italy, Portugal, Greece and Spain.

In many Member States the proportion of general upper secondary students learning two or more foreign languages has stagnated or fallen compared with 2008 levels.

In terms of the average number of foreign languages studied as part of compulsory education, Luxembourg takes first place (three languages), followed by Finland (2.7), Belgium and Estonia (2.2). Pupils enrolled in upper secondary education in Sweden, France and most Eastern European countries study on average at least two foreign languages. In contrast, students in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Portugal learn less than one foreign language on average. Only a few countries have expanded the number of foreign languages taught in mandatory curriculums over the past eight years, in particular Malta, Luxembourg, Latvia, Cyprus, Germany and Italy.

English was the most studied foreign language across the EU, with 96.7 % of students learning it in 2012 (at ISCED level 2). This represents a substantial increase in its popularity, compared with 75.4 % a decade earlier. French, German and especially Spanish have also been steadily gaining popularity over that time.

ICT skills: enhancing digital competences

Enhancing digital competences to exploit the potential of information and communication technologies (ICT) is a key priority under the Europe 2020 strategy. Its flagship initiative ‘Digital Agenda for Europe’ aims to help achieve this goal. The lack of digital literacy and skills is seen as ‘excluding many citizens from the digital society and economy. It is also holding back the large multiplier effect of ICT take-up on productivity growth’ [15].

ICT skills are also relevant to the Europe 2020 strategy’s headline indicator on R&D expenditure. An analysis of European citizens’ computer and internet skills is provided in the `R&D and innovation' article.

How tertiary education and life-long learning contribute to the EU’s human capital

The proportion of tertiary graduates is growing rapidly

Raising the share of the population aged 30 to 34 that have completed tertiary or equivalent education to at least 40 % is the second of the two Europe 2020 education targets. It is monitored with the headline indicator that follows tertiary educational attainment of the same age group.

Figure 7 shows a steady and considerable growth in the share of 30 to 34 year olds who have successfully completed university or other tertiary-level education since 2002. The 13.3 percentage point growth over the period 2002 to 2013 equals an increase of about 57 % in tertiary graduates in the EU [16].

Women significantly outnumber men in tertiary educational attainment

Figure 8 shows a significantly widening gender gap among tertiary education graduates across the EU. While in 2002 the share of 30 to 34 year olds with tertiary educational attainment was similar for both sexes, the increase up to 2013 was almost twice as fast for women. In 2013 women outnumbered men significantly in terms of tertiary educational attainment in all Member States. In fact, 15 Member States showed a gender gap of more than 10 percentage points in 2013, and in Estonia and Latvia the differences were more than 20 percentage points.

Gender differences can also be seen in the fields studied. A significantly higher proportion of men than women graduate in mathematics, science or engineering subjects. Women tend to dominate education, humanities, art and service-oriented fields [17].

Northern and Central Europe show the highest tertiary educational attainment levels

The trend in the EU as a whole mirrors increases in tertiary educational attainment levels across all EU Member States. This to some extent reflects Member States’ investment in higher education to meet demand for a more skilled labour force. Moreover, the increases can also be ascribed to the shift to shorter degree programmes following implementation of Bologna [18] process reforms in some Member States [19].

National targets for tertiary education [20] range from 26 % for Italy to 66 % for Luxembourg. Austria and Germany’s targets are slightly different from the overall EU target because they include post-secondary attainment (ISCED level 4 for Germany, and ISCED level 4a for Austria). This is considered equivalent to university education in these two countries. For France the target definition refers to the age group of 17 to 33 year olds while for Finland the target is based on a narrower national definition which excludes former tertiary vocational education and training (VET).

In 2013, 13 countries had already achieved their national targets: Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Greece, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, the Netherlands, Austria, Slovenia, Finland and Sweden. Spain, Italy and Romania were close at less than four percentage points from their national targets. Croatia, Luxembourg, Portugal and Slovakia were the most distant, at some 10 percentage points or more below their targets.

Levels of tertiary educational attainment varied by a factor of about 2.5 across Europe in 2013. Northern and Central Europe had the highest percentage of tertiary graduates, with 16 countries exceeding the overall EU target of 40 %. The lowest levels could be observed in Italy and Romania, which were both below 25 %.

At the same time, some Eastern European countries experienced the strongest increases over the period 2008 to 2013. Changes were most pronounced in the Czech Republic, Latvia, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, with shares growing by more than 140 %.

Looking at non-EU Europe, the EFTA countries Norway, Switzerland and Iceland were at the level of the best performing EU Member States in 2013. However, the candidate countries The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Turkey showed tertiary educational attainment levels similar to Southern and Eastern European Member States.

The regional differences in tertiary educational attainment across Europe shown in Map 4.3 are to a large extent in line with general country differences (see Figure 9). In 2013 many regions in France, the United Kingdom, Finland and Sweden had above average rates. On the other hand, most regions in Italy, Hungary and Romania showed a very small proportion of tertiary graduates.

Czech Republic and Romania showed the biggest within-country dispersion of tertiary educational attainment rates, with factors of 3.4 and 3.1. This means the worst performing regions had rates that were more than three times as low as the best performing regions. In contrast, Ireland, Slovenia and Croatia were the most ‘equal’ countries, with almost no disparities in tertiary educational attainment rates across their regions.

Map 4 shows the change in regional tertiary educational attainment rates since 2008. Of the 297 NUTS 2 regions for which data are available, 85.2 % (or 253 regions) experienced an increase in the share of the population that has attained a tertiary education between 2008 and 2013. Among the regions with the highest increases are capital regions such as Bratislavský kraj (Slovakia), Praha (Czech Republic) and London (United Kingdom).

In contrast, 43 regions experienced a fall in tertiary educational attainment rates over the period from 2008 to 2013. Nine regions had falls of more than four percentage points. Two of these were in France (Languedoc-Roussillon and Auvergne), three were in the United Kingdom (Devon, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly and Merseyside) and the remaining four in Spain (Castilla y León), Bulgaria (Severen tsentralen), Finland (Etelä-Suomi) and Belgium (Prov. Luxembourg).

Low levels of student mobility in higher education

Apart from providing valuable academic and cultural benefits, educational mobility is increasingly important for improving young people’s employability and access to the labour market [21]. Increased mobility in higher education — of students, researchers and staff — has been established as a key priority area within the framework of the Bologna Process [22]. In 2009, European ministers responsible for higher education met to take stock of the achievements of the Bologna Process. They agreed on the benchmark that ‘in 2020 at least 20 % of those graduating in the European Higher Education Area should have had a study or training period abroad’ [23]. The benchmark refers to two main forms of mobility: degree mobility (undertaking a full degree programme in another country) and credit mobility (taking part of a study programme in a university abroad) [24].

Direct assessment of Member States’ progress towards the EU mobility benchmark cannot be made because the current data on students going abroad do not provide information on graduates’ degree and credit mobility. Nevertheless, statistics on student enrolment in higher education provide a useful indication of general mobility trends. In 2012 the average mobility rate for the EU was rather low, at 3.5 % for incoming and 3.4 % for outgoing students. This average, however, obscures huge variation across Member States. More than half of tertiary students from Cyprus, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein were enrolled in another European country in 2012 (see Figure 10). Limited provision of study places within their own educational system is the most likely reason for this. In contrast, 11 EU Member States showed rather low outbound mobility levels below 3 %, in particular the United Kingdom and Spain. Many Eastern European countries had a significant flow of outgoing students, but very few incoming ones.

Inbound mobility can generally be seen as a sign of the attractiveness of a country’s higher education and its financial and institutional capacity for enrolling foreign students [25]. Outward mobility, on the other hand, might be a result of policies encouraging students to spend part of their studies abroad (credit mobility in particular) [26].

Learning as a lifelong process

In addition to tertiary educational attainment, lifelong learning is also crucial for providing Europe with highly qualified labour force. Adult education and training covers the longest time span in the process of learning throughout a person’s life. After an initial phase of education and training, continuous, lifelong learning is crucial for improving and developing skills, adapting to technical developments, advancing one’s career or returning to the labour market [27] (also see the ‘Employment’ article). In recognition of this, lifelong learning plays a crucial role in the Europe 2020 flagship initiatives ‘[Youth on the move]’ and ‘[An Agenda for new skills and jobs]’. In addition, the European Council in 2011 adopted a resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning [28]. The EU’s ET 2020 framework also includes a benchmark that aims to raise the share of adults participating in lifelong learning [29] to at least 15 %.

After growing between 2003 and 2005, the share of EU adults participating in lifelong learning fell slightly to about 9 % in 2012. It increased to 10.5 % in the following year, but this rise was mainly influenced by a methodological change to the French Labour Force Survey [30].

From 2012 to 2013, participation in lifelong learning increased in 15 countries. Over the whole period 2002 to 2013, nine countries experienced a substantial increase of more than five percentage points: Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Portugal, Luxembourg, Spain, Austria and France. In 2013, only five EU countries from Northern Europe (Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) as well as France exceeded the ET 2020 benchmark. In 13 Member States participation in lifelong learning was less than half the required level of 15 %. In 2013, participation rates in lifelong learning in Bulgaria (1.7 %), Romania (2.0 %), Croatia and Slovakia (2.9 % each) were more than 20 percentage points lower than in Finland (24.9 %), Sweden (28.1 %) and Denmark (31.4 %).

Women, migrants, highly educated people and employed people participate more in lifelong learning

Women are more likely to participate in lifelong learning than men. In 2013, the share of women engaged in lifelong learning was 1.8 percentage points higher than for men (11.4 % as opposed to 9.6 %). Men, however, show a higher preference for non-formal job-related learning.

The foreign-born population also tends to be slightly more involved in lifelong learning activities (11.9 % in 2013). This may reflect participation in targeted learning activities such as language courses. It may also be linked to higher unemployment rates among migrants in some countries, resulting in a greater participation in labour market integration measures [31] (see article on ‘Employment’).

There is a clear gradient of participation in lifelong learning and a person’s educational attainment. In 2013, people with at most lower secondary education were much less engaged in lifelong learning (4.4 %) than those with upper secondary (8.7 %) or tertiary education (18.6 %).

In relation to labour status, employed people in general show a slightly higher participation rate in lifelong learning. Some 11.3 % of employed 25 to 64 year olds took part in lifelong learning in 2013. For unemployed people, the rate was slightly lower than the total participation rate, at 9.9 %.

Entrepreneurial skills are crucial for the transition towards a knowledge-based society

The EU’s framework for key competences identifies and defines the key abilities and knowledge that a person needs to achieve employment, personal fulfilment, social inclusion and active citizenship in today’s rapidly changing world [32]. In this context, entrepre-neurship competences are defined as an individual’s ability to turn ideas into action. This transversal set of skills refers to creativity, innovation and risk-taking as well as general management skills needed to achieve objectives [33].

Enhancement of entrepreneurial skills is endorsed as a key long-term priority in the ET 2020 framework. The Europe 2020 strategy also recognises it is crucial to the transition to a knowledge-based society. The importance of enhancing creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship through education is highlighted in three flagship initiatives: ‘Youth on the move’, ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs’ and ‘Innovation Union’.

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) provides a source of annual country data on the population’s perceived levels of entrepreneurship skills, based on adult population surveys. The GEM project is run by a consortium of universities with special teams of experts from almost 100 participating countries [34]. Figure 12 shows that in 2013 at least 50 % of the adult population in four EU Member States believed they have the skills and knowledge to start a business. Poland takes the lead with more than half its working-age population expressing good self-perceived entrepreneurial capabilities. However, in most Nordic countries, as well as in Italy and France, fewer adults display confidence in their competences. It should be noted that differences in attitudes might reflect not only levels of entrepreneurial education and training, but also factors such as individuals’ levels of confidence or voluntary training beyond formal education [35].

Education levels and labour market participation

Younger people show higher educational attainment levels

Educational attainment is the visible output of education systems. Achievement levels can have major implications for many issues touching a person’s life. This is reflected in participation in lifelong learning as well as in other aspects presented in the articles on ‘Employment’ and ‘Poverty and social exclusion’.

Upper secondary education is now considered the minimum desirable attainment level for European citizens leaving the education and training system. This is reflected in the Europe 2020 headline indicator on early leavers from education and training. Figure 13 shows the share of the population that has completed upper secondary or tertiary education, broken down by sex and age groups.

In 2013, more than 80 % of 20 to 34 year olds had completed at least upper secondary education, while the share for the age group 55 to 64 was lower, at 66 %. This difference reflects the growing demand for a more highly skilled workforce in most parts of Europe over the past few decades. A more skilled workforce is expected to emerge as older groups steadily leave the workforce and are replaced by a younger, more highly educated generation. If labour markets do not provide adequate jobs this may result in certain levels of over-qualification and youth unemployment [36]. For older workers aged 55 to 64, lower educational attainment levels, especially among women, highlight the importance of lifelong learning to increase their employability and help meet the Europe 2020 strategy’s employment target (see the article on ‘Employment’).

Educational attainment is highest in Eastern Europe, where upper secondary education has long been the standard [37]. Southern European countries in contrast show the lowest education levels. In 2013, less than half the population aged 25 years or over living in Spain, Italy, Malta and Portugal had completed more than lower secondary education. However, these countries have shown the strongest improvements over time, with education levels among 20 to 24 year olds being about twice as high as among those close to retirement.

Figure 13 also shows how women have overtaken men in educational attainment. While in the age group 45 to 64 years attainment is higher for men, the situation is turned around in the population aged 44 and younger. This trend illustrates the gender differences observed for a number of the indicators analysed in this article, such as early leavers from education and training, tertiary education and participation in lifelong learning.

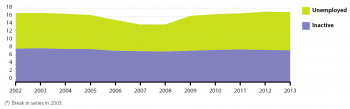

Consequences of low educational attainment

Low educational attainment — at most lower secondary education — is usually negatively linked with other socioeconomic variables. The most important of these are employment, unemployment and the risk of poverty or social exclusion. Some of these relationships are also analysed in detail in the respective articles(see the articles on ‘Employment’ and ‘Poverty and social exclusion’).

Early leavers from education and training and low-educated young people face particularly severe problems in the labour market. As shown in Figure 14, about 60 % of 18 to 24 year olds with at most lower secondary education and who were not in further education or training were either unemployed or inactive in 2013. Of these, two thirds stated they would like to work. At the same time, the EU’s overall youth unemployment rate, covering the age group 15 to 29 years, stood at 18.7 %. This implies that unemployment levels among early leavers from education and training are much higher than among the total population of the same age group [38]. For a further analysis on youth unemployment see the articles on ‘Employment’.

Compared with the overall decline in early leaving from education and training, Figure 14 shows it is becoming more difficult for early school leavers to find work. Between 2008 and 2013, the share of 18 to 24 year old early leavers who were not employed but wanted to work grew from less than one-third to more than 40 %.

Young people neither in employment nor in education and training face a high risk of being excluded from the labour market

The indicator monitoring young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET) covers people aged 18 to 24 years. Low educational attainment is one of the key determinants of young people entering the NEET category [39]. Other factors include having a disability or coming from a migrant background.

In 2013, 17.0 % of 18 to 24 year olds were in the NEET status, putting them at risk of being excluded from the labour market and becoming dependent on benefits. This represents a considerable increase since 2008, when the NEET rate stood at a low of 13.9 %.

As shown in Figure 15, the EU’s NEET rate has been largely influenced by changes in unemployment for 18 to 24 year olds. In comparison, the share of inactive youths has remained stable at or slightly below 8 %. The rate is slightly higher for women than for men, although the gender gap has closed slightly since the economic crisis began in 2008. In 2013, the NEET rate for 18 to 24 year old women was 17.4 %, with more than half (54.6 %) being economically inactive. At the same time, the NEET rate for men of the same age group was 16.6 %, but almost two-thirds (63.9 %) were unemployed.

Low educational attainment negatively influences quality of life

The negative impacts of low educational attainment described here and in the articles on ‘Employment’ and ‘Poverty and social exclusion’ also influence other aspects of a person’s perceived quality of life [40]. Across the EU, the perception of being in good or very good health in 2012 was highest among people having completed tertiary education (81.6 %). Only slightly more than half (55.1 %) of the people with at most lower secondary educational attainment shared this perception.

Matching skills with labour market needs

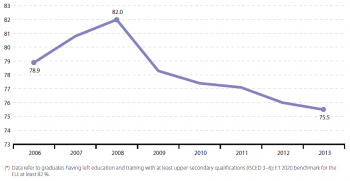

The EU’s ET 2020 framework acknowledges the important role of education and training in raising employability. It has set a benchmark that at least 82 % of graduates (20 to 34 year olds) should have found employment no more than three years after leaving education and training [41].

Figure 16 shows that recent graduates have been affected particularly strongly by the economic crisis. Between 2008 and 2013, employment rates among 20 to 34 year olds who had left education and training in the past one to three years fell by 6.6 percentage points. In comparison, the decline in the overall employment rate for 20 to 64 year olds was ‘only’ 1.9 percentage points over the same period.

The data in Figure 16 refer to graduates having left education and training with at least up-per-secondary qualifications (ISCED levels 3 to 6). Disaggregation by educational attainment reveals that the fall in the employment rate has been stronger for the lower educated cohort (– 7.6 percentage points since 2008) than for those with tertiary education (– 6.0 percentage points since 2008). This is in line with trends in the overall employment rate (see the article on ‘Employment’), and underlines the importance of educational attainment for employability.

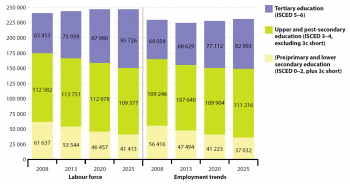

Matching educational outcomes and labour market needs is a key component of the Europe 2020 strategy (see the article on ‘Employment’). ‘Equipping people with the right skills for employment’ has been identified as one of four priorities of the flagship initiative ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs’. In particular the impact of the economic crisis and persistently high unemployment have increased the need to better understand where future skills shortages are likely to lie in the EU [42]. Most recent forecasts from the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) [43] indicate that between 2013 and 2025 some 20 million jobs requiring high educational attainment will be created, while at the same time low-qualified jobs will decline by about more than 10 million.

Figure 17 mirrors these estimates with projected changes in the EU labour force. The population holding a university degree or equivalent is expected to grow by more than 25 % between 2013 and 2025. In comparison, the number of low-skilled people will fall by more than 20 %.

Overall, the Cedefop forecasts show a parallel rise in skills from both the demand and the supply side until 2020. Changes in skills levels are expected to occur faster for the labour force than in employment trends. This parallel rise does not prevent potential skills mismatches, such as over--qualification gaps [44].

Investment in future generations: the case of public expenditure on education

Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP is often considered an indicator of how committed a government is to developing skills and competences.

Two developments have had major impacts on the role of education and training systems: the recent economic crisis and the ageing of the population. The financial and economic crisis has affected EU labour markets, economies and societies in general. Population ageing across most Member States affects educational systems through its impacts on the labour market and public finances [45].

Investment in education is essential for facing both of these challenges. It helps foster economic growth and productivity, and enhances innovation and competitiveness. While fiscal and monetary policies can counteract the adverse effects of the crisis in the short run, investment in education is a necessary policy measure for addressing its long-term impacts on unemployment. Not only can human capital accumulation reduce pressure on labour markets during an economic crisis, it can also compensate for the projected shrinking labour force in European economies [46].

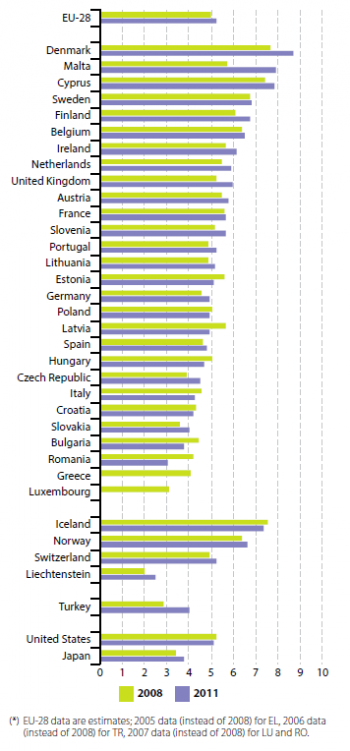

As shown in Figure 18, public expenditure on education as a % of GDP slightly increased in the EU, from 5.0 % in 2008 to 5.3 % in 2011. This average figure conceals considerable cross-country variations in the allocation of public resources for education, ranging from 3.1 % in Romania to 8.8 % in Denmark in 2011.

Education systems across the EU have been affected differently by the recession. This partly reflects the extent to which the crisis has hit national economies. While 11 countries have managed to keep their spending on education at a higher or comparable level in absolute terms from 2008 to 2011, cuts in education expenditure were significant during this period in Estonia, Ireland, Latvia and Hungary as well as in Bulgaria, Greece, Italy and Romania, where spending levels in relation to the GDP were already low and have been cut further. The European Commission considers the fall in education spending in recent years in these Member States a worrying trend calling for strengthening the efficiency of education investment and supporting innovation and competitiveness. This is of particular relevance in the context of limited GDP growth forecasts for 2014 [47].

Students from disadvantaged groups most affected by cutbacks on education

Economic downturns and education cutbacks are likely to affect students from disadvantaged back-grounds particularly severely [48]. This is because disadvantaged children often tend to be concentrated in schools with fewer resources. Furthermore, households from higher socioeconomic backgrounds might have the financial resources to compensate for the reduction in support at school through private tuition, for example. Disadvantaged students have much fewer options for overcoming these obstacles.

Apart from general funding mechanisms for allocating resources across different educational levels, governments can also provide additional educational support to disadvantaged students by awarding specific programme funds. These funds can be distributed according to predefined need-based criteria targeting, for example, specific geographic, social, language or other groups [49].

The targeted support could cover a variety of programmes ranging from language classes for minority groups and improvement in student–teacher ratio to general schemes that reduce student drop-out rates. In some Member States, such as the Czech Republic and Ireland, crisis-led adjustments included a reduction in the number of support teachers in schools, or supplementary programmes targeting low-performing or migrant students. In contrast, against the background of austerity measures, Belgium (French and Flemish Communities) and Spain have reported an increase in their budgets for specific support programmes. The United Kingdom (England and Wales) has taken similar measures by making available new support funds for students from disadvantaged backgrounds [50].

Conclusions and outlook towards 2020

Early leaving from education and training has fallen continuously in the EU since 2002, for both men and women. The fall from 17.0 % in 2002 to 12.0 % in 2013 represents steady progress towards the Europe 2020 target. Young men, foreign-born residents and ethnic minorities are more likely to leave education and training with at most lower secondary education. While in 2013 women were already close to the overall EU target at 10.2 %, the rate was much higher for men at 13.6 %.

Improvements have also been visible in the second Europe 2020 headline indicator. Between 2002 and 2013, the share of 30 to 34 year olds having completed tertiary education grew continuously from 23.6 % to 36.9 %. Growth was considerably faster for women, who in 2013 were already above the Europe 2020 target. In contrast, only 32.7 % of 30 to 34 year old men had completed tertiary education in the same year.

Educational attainment strongly influences successful participation in the labour market. In 2013, 59 % of 18 to 24 year old early leavers from education and training were either unemployed or inactive. Of the total population of 18 to 24 year olds, 17 % were neither in employment nor in any further education or training (NEET) and thus at risk of being excluded from the labour market. This is also reflected in the youth unemployment rate, which was particularly high for low-educated 15 to 24 year olds (see article on ‘Employment’).

Progress in the other education indicators for which benchmarks have been set in the EU’s ET 2020 framework is mixed. Participation in early childhood education and care (ECEC) has grown more or less continuously in the EU since 2001. In 2012, 93.9 % of children between the age of four and the starting age of compulsory education participated in ECEC, compared with 86.6 % in 2001. This is a considerable move towards the ET 2020 benchmark of at least 95 %.

The picture is less optimistic when it comes to basic skills such as reading, maths and science. In 2012 about one-fifth of 15 year olds showed insufficient abilities in reading, maths and science. This means that a reduction of almost a third will be necessary to reach the ET 2020 benchmark. In 2012, the average EU mobility rate taking into account only degree mobility was around 3 %. However, this masks huge differences across Europe and between incoming and outgoing students.

In relation to adult education, which is important because it covers the longest time span in the process of lifelong learning, the share of adults participating in lifelong learning does not seem to be increasing at a pace fast enough to meet the ET 2020 benchmark of raising the share of adults engaging in lifelong learning activities to at least 15 % by 2020.

Last, in relation to the important role of education and training in improving employability, the em-ployment rate of recent graduates (20 to 34 year olds having left education and training in the past three years) has dropped considerably since the economic and financial crisis began. It has fallen from 82 % in 2008 to 75.4 % in 2013. This trend, which shows that the targeted age group has been affected particularly strongly by the crisis, has moved the EU away from the ET 2020 benchmark of raising the employment rate of recent graduates to at least 82 % by 2020.

Forecasts concerning the skills required by the labour market up to 2025 underline the importance of higher education. Between 2013 and 2025 some 20 million jobs requiring medium or high qualifications are expected to be created, whereas at the same time low-qualified jobs will fall by about 12 million.

Efforts needed to meet the Europe 2020 targets on education

Knowledge about current student cohorts and the existing demographic projections allow estimations of educational trends up to 2020, which can help identify priority issues that may need particular political attention on the path towards meeting the Europe 2020 targets. For example, students who are now in their mid-20s will in 2020 fall within the scope of the Europe 2020 headline indicator on ‘tertiary educational attainment’, which looks at education levels of the population aged 30 to 34 years.

The flagship initiatives ‘Youth on the move’ and ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs’ address the challenge of early leaving from education and training. In 2011, the European Council published recommendations on policies to reduce early leaving from education and training [51], giving guidance to Member States on the implementation of strategies and measures tackling this problem. Vocational Education and Training (VET) systems are seen as an important contribution to the employability of young people and the reduction of early leaving from education and training, by offering an interesting alternative to general education [52].

Additionally, the Europe 2020 strategy puts particular efforts on making sure that higher education courses develop skills profiles relevant to the world of work, both for meeting future labour demand and for ensuring the long-term attractiveness of higher education [53]. Moreover, the European Council’s Resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning [54] addresses the challenge of raising participation rates of adults in lifelong learning activities.

Data sources and availability

ET 2020 — the EU’s Strategic Framework for Education and Training 2020

The two Europe 2020 targets are embedded in the broader Strategic Framework for Education and Training 2020 (ET 2020) [55]. ET 2020 aims to foster European cooperation in education and training, providing common strategic objectives for the EU and its Member States for the period up to 2020. ET 2020 covers the areas of lifelong learning and mobility; quality and efficiency of education and training; equity, social cohesion and active citizenship; creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship at all levels of education and training. To support the achievement of these objectives ET 2020 sets EU-wide benchmarks. Apart from the two Europe 2020 targets for education, there are six additional benchmarks:

- An average of at least 15 % of adults should participate in lifelong learning.

- The share of low-achieving 15 year olds in reading, mathematics and science should be less than 15 %.

- At least 95 % of children between the age of four years and the age for starting compulsory primary education should participate in early childhood education.

- An EU average of at least 20 % of higher education graduates should have had a period of higher education-related study or training (including work placements) abroad, representing a minimum of 15 ECTS credits [56] or lasting a minimum of three months.

- An EU average of at least 6 % of 18 to 34 year olds with an initial vocational education and training (VET) qualification should have had an initial VET-related study or training period (including work placements) abroad lasting a minimum of two weeks, or less if documented by Europass [57].

- The share of employed graduates (20 to 34 year olds) having left education and training no more than three years before the reference year should be at least 82 %.

EU initiatives promoting mobility in higher education

The EU has set up a number of initiatives to promote mobility in higher education under the Lifelong Learning Programme [58], including Erasmus for study exchanges and placements[59], Erasmus Mundus for postgraduate studies[60], Leonardo Da Vinci for vocational education and training[61], Marie Curie for research fellowships [62] and Grundtvig for adult education [63].

For the period 2014 to 2020, the activities of the Lifelong Learning Programme continue under the new Erasmus+ programme, which integrates seven earlier programmes in the fields of education, youth and culture [64]. The programme has received 40 % higher budget compared with the previous programming period.

As part of the Europe 2020 strategy, the flagship initiative ‘Youth on the move’ [65] also aims to extend opportunities for learning mobility to all young people in Europe, mainly through financial support and dissemination of information.

Erasmus was part of the EU’s lifelong learning programme. Erasmus mobility, with its core focus on skills development, is a central element of the European Commission’s strategy to combat youth unemployment, featuring prominently in the Europe 2020 strategy for growth and jobs.

During the academic year 2012–2013 nearly 270 000 students from 33 European countries spent time abroad with an Erasmus grant. Since the programme began in 1987–1988, it has provided more than three million European students with the opportunity to go abroad and study at a higher education institution or train in a company [66].

Policies tackling the transition from education to employment

The EU employment package ‘Towards a job-rich recovery’, under its objective of restoring the dynamics of labour markets, calls for ‘security in employment transitions’, such as in the transition of young people from education to work: ‘there is evidence to show that apprenticeships and quality traineeships can be a good means of gaining entry into the world of work, but there are also recurring examples of traineeships being misused’.

The employment package also reaffirms the European Commission’s commitment to tackle the dramatic levels of youth unemployment by supporting the transition to work ‘through youth guarantees, activation measures targeting young people, the quality of traineeships and youth mobility’ [67].

Projections up to 2020 in relation to the Europe 2020 education targets

Based on the most recent data for early school leaving and tertiary education, the European Commission has published projections of the likelihood that Europe 2020’s education targets will be met by 2020:

- The EU average early school leaving rate in 2010 was 13.9 % and it would need to be below 10 % by 2020, ten years later. It follows from a basic calculation that the minimum annual progress required for the EU as a whole during this period is – 3.3 %, whereas the observed annual progress for the EU between 2010 and 2013 has been – 5.1 %. This means that the EU on average is on track and that the headline target is within reach if current progress is sustained [68].

- The EU average tertiary attainment rate in 2010 was 33.4 % and it would need to reach 40 % ten years later. The resulting minimum annual progress required for the EU as a whole is 1.8 %, while the observed annual change between 2010 and 2013 has been considerably higher (3.3 %). This means that the EU is well on track to reach its 40 % target by 2020 if recent progress can be sustained [69].

Of the 12.4 million 30 to 34 year olds with a tertiary education qualification, 6.8 million are women. This highlights a significant gender difference in relation to obtaining a high-level education. Moreover, this difference is increasing, up by 0.7 percentage points from 2011. In fact, women, taken as a separate group, achieved the 40 % benchmark in 2012, eight years ahead of the 2020 target date [70].

Context

Education and training - why do they matter?

Education and training lie at the heart of the Europe 2020 strategy and are seen as key drivers for growth and jobs. The recent economic crisis along with an ageing population, through their impact on economies, labour markets and society, are two important challenges that are changing the context in which education systems operate [71]. At the same time education and training help boost productivity, innovation and competitiveness [72].

Nowadays upper secondary education is considered the minimum desirable educational attainment level for EU citizens. Young people who leave education and training prematurely lack crucial skills and run the risk of facing serious, persistent problems in the labour market and experiencing poverty and social exclusion. Early leavers from education and training who do enter the labour market are more likely to be in precarious and low-paid jobs and to draw on welfare and other social programmes. They are also less likely to be ‘active citizens’ or engage in lifelong learning [73].

In addition, tertiary education, with its links to research and innovation, provides highly skilled human capital (see the article on ‘R&D and innovation’) A lack of these skills presents a severe obstacle to economic growth and employment in an era of rapid technological progress, intense global competition and labour market demand for ever-increasing levels of skill. The Europe 2020 strategy, through its ‘smart growth’ priority, therefore aims to tackle early school leaving and to raise tertiary education levels [74].

The analysis in this article builds on the headline indicators chosen to monitor the strategy’s education targets: ‘Early leavers from education and training’ and ‘Tertiary educational attainment’. Contextual indicators are used to provide a broader picture and insight into drivers behind changes in the headline indicators. Some are also used to monitor progress towards additional benchmarks set under the EU’s Strategic Framework for Education and Training 2020 (ET 2020). These indicators include early childhood education, basic reading, maths and science skills and adult participation in lifelong learning. The benchmarks are listed in the section 'Data sources and availability'.

The presentation of the headline and contextual indicators starts with early leaving from education and training, followed by early childhood education, acquisition of basic skills (reading, maths and science) and foreign languages, leading to tertiary education and lifelong learning in adulthood. The analysis then switches to the ‘outcome’ side. Here it looks at educational attainment in the EU labour force and the impacts of low levels of attainment. Last, it investigates the input into the education system, in the form of public expenditure on education.

The EU’s education targets are interlinked with the other Europe 2020 goals: higher educational levels help employability and progress in increasing the employment rate in turn helps to reduce poverty [75]. The tertiary education target is furthermore interrelated with the research and development (R&D) and innovation target. Investments in the R&D sector will raise demand for highly skilled workers (see the article on ‘R&D and innovation’).

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Towards robust quality management for European Statistics - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council COM(2011) 211 final

Other information

- Regulation 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

External links

Notes

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels, 2014

- ↑ The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, see p. 193.

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 18); International Organization for Migration, Foreign-born Children in Europe: An Overview from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study, 2009 (p. 36).

- ↑ Dale et al., Early School leaving: Lessons from Research for Policy Makers, European Commission, 2010 (p. 30).

- ↑ European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights & UNDP, The Situation on Roma in 11 EU Member States, 2012 (p. 14)

- ↑ Speech of Morten Kjaerum, Director of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Exclusion and Discrimination in Education: The Case of Roma in the European Union, 8 April 2013.

- ↑ European Commission, EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020, COM(2011) 173 final, Brussels, 2011.

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/europe-2020-in-a-nutshell/targets/index_en.htm.

- ↑ European Commission, Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe: 2014 (p. 11)

- ↑ European Commission, Early Childhood Education and Care: Providing All our Children with the Best Start for the World of Tomorrow, COM(2011) 66 final, Brussels, 2011 (p. 1 and p. 5).

- ↑ European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights & UNDP, The Situation on Roma in 11 EU Member States, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 13).

- ↑ European Commission, Early Childhood Education and Care: Providing All our Children with the Best Start for the World of Tomorrow, COM(2011) 66 final, Brussels, 2011 (p. 4).

- ↑ PISA is an international study that was launched by the OECD in 1997. It aims to evaluate education systems worldwide every three years by assessing 15-year-olds’ competencies in the key subjects: reading, mathematics and science. For further details see http://www.oecd.org/pisa/

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2013, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2013 (p. 36).

- ↑ European Commission, A Digital Agenda for Europe, COM(2010) 245 final, Brussels, 2010 (p. 6).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2013, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2013 (p. 40)

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2013, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2013 (p. 42).

- ↑ The Bologna Process has created a European Higher Education Area (EHEA) to connect national educational systems. The intention is to allow the diversity of national systems and universities to be maintained while the European Higher Education Area improves transparency between higher education systems, as well as implements tools to facilitate recognition of degrees and academic qualifications, mobility, and exchanges between institutions. (source: EUA (European University Association (accessed 05 August 2014).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2013, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2013 (p. 40)

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/europe-2020-in-a-nutshell/targets/index_en.htm.

- ↑ Eurydice (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency), The European Higher Education Area in 2012: Bologna Process Implementation Report, 2012 (p. 153).

- ↑ The Bologna Process is an intergovernmental initiative involving the European Commission, the European Council and UNESCO-CEPES as well as representatives of higher education institutions, students, staff, employers and quality assurance agencies. It was aimed at creating a European Higher Education Area by 2010, and to promote the European system of higher education worldwide. For further details see http://ec.europa.eu/education/higher-education/bologna_en.htm.

- ↑ Communiqué of the Conference of European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education, The Bologna Process 2020 — The European Higher Education Area in the new decade, Leuven and Louvain-la-Neuve, 28–29 April 2009.

- ↑ Eurydice (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency), The European Higher Education Area in 2012: Bologna Process Implementation Report, 2012 (p. 153).

- ↑ Eurostat, Key indicators on the social dimension and mobility: The Bologna Process in Higher Education in Europe, 2009 edition, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2009 (p. 98).

- ↑ Eurydice (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency), *The European Higher Education Area in 2012: Bologna Process Implementation Report, 2012 (p. 153).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 48).

- ↑ Council Resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning (2011/C 372/01), Official Journal of the European Union, 20.12.2011.

- ↑ The benchmark of 15 % refers to persons aged 25 to 64 who stated that they received education or training in the four weeks preceding the survey.

- ↑ INSEE, the French Statistical Office, has carried out an extensive revision of the questionnaire of the Labour Force Survey. The new questionnaire was used from 1 January 2013 onwards. It impacts significantly the level of various French LFS-indicators. Detailed information on these methodological changes and their impact is available in INSEE’s website http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/info-rapide.asp?id=14 Box ‘Pour en savoir plus’. Due to this revision, comparisons with the past should be avoided, both for the French data and for the EU aggregates, which are also affected. In particular, the variable EDUCSTAT (participation in regular/formal education during the last 4 weeks) has been calculated from 2013 based on a question on formal education (and no longer on initial education); this has some (rather minor) impact on the number of students aged 25–64. The variable COURATT (participation in non-formal education during the last 4 weeks) from 2013 covers all non-formal education and training activities (4 questions are asked instead of 1 question = the implementation of the variable in the questionnaire changed and now covers/catches these activities better). As a result the participation in non-formal activities triples for the age group 25-64, and this change explains the change in the overall LLL indicator. The online table ‘ (trng_lfs_09)’ provides the breakdown by formal / non-formal and age group for further evaluation of the change in the percentages. Given the share of France in the population 25–64 in 2013 (about 12.2 %) the impact of this methodological change in France has been assessed by Eurostat as having had an impact of about 1.5 % on the EU-28 average.

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2013, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013 (p. 68)

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/key_en.htm.

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 39).

- ↑ For further details see http://www.gemconsortium.org.

- ↑ Alicia Coduras Martínez et al., Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Special Report: A Global Perspective on Entrepreneurship Education and Training, Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 2010 (p. 30).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 54).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 54).

- ↑ European Commission, Early School Leaving (accessed 23 July 2013).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2011, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 28).

- ↑ Breakdowns of several ‘Quality of Life’ (QoL) indicators are available in a dedicated section on Quality of Life indicators on the Eurostat website: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/gdp_and_beyond/quality_of_life/context.

- ↑ Council conclusions of 11 May 2012 on the employability of graduates from education and training (2012/C 169/04), Official Journal of the European Union, 15.6.2012.

- ↑ European Commission, ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs: A European contribution towards full employment, COM(2010) 682 final, Strasbourg, 2010 (p. 8).

- ↑ The Cedefop skills forecasts are available at http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/EN/about-cedefop/projects/forecasting-skill-demand-and-supply/skills-forecasts.aspx.

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture),[ http://ec.europa.eu/education/tools/et-monitor_en.htm Education and Training Monitor 2012], Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 57).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 7).

- ↑ Bilal Barakat, Johannes Holler, Klaus Prettner, and Julia Schuster, The Impact of the Economic Crisis on Labour and Education in Europe, Vienna Institute of Demography, 2010 (p. 12).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2013, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2013 (p. 14).

- ↑ OECD, Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools, 2012 (p. 31).

- ↑ European Commission, Funding of Education in Europe 2000–2012: The Impact of the Economic Crisis, 2013 (p. 69).

- ↑ European Commission, Funding of Education in Europe 2000–2012: The Impact of the Economic Crisis, 2013 (p.69).

- ↑ Council recommenda-tions of 28 June 2011 on policies to reduce early school leaving (2011/C 191/01), Official Journal of the European Union, 1.7.2011.

- ↑ European Commission, Regulation Youth on the Move: An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union, COM(2010) 477 final, Brussels, 2010 (p. 6); European Commission, Early School Leaving (accessed 23 July 2013).

- ↑ European Commission, Tertiary Education (accessed 04 July 2014).

- ↑ European Commission, Regulation Youth on the Move: An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union, COM(2010) 477 final, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ Council conclusions of 12 May 2009 on a strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (‘ET 2020’) (2009/C 119/02), Official Journal of the European Union, 28.5.2009.

- ↑ ECTS is the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System. The system allows for the transfer of learning experiences between different institutions, greater student mobility and more flexible routes to gain degrees. It also aids curriculum design and quality assurance. For further details, see http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/ects_en.htm.

- ↑ Europass is a common European standard for making skills and qualifications clearly and easily understood across Europe. It includes five documents, two of which are completed by European citizens themselves (Curriculum Vitae and Language Passport) and three of which are issued by education and training authorities (Europass Mobility, Certificate Supplement, Diploma Supplement). For further details see http://europass.cedefop.europa.eu/en/about.

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-programme/index_en.htm.

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/education/erasmus/students_en.htm.

- ↑ Seehttp://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-programme/erasmus_en.htm.

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-programme/ldv_en.htm.

- ↑ Seehttp://ec.europa.eu/research/mariecurieactions/about-mca/actions.

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/education/grundtvig/what_en.htm.

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/index_en.htm.

- ↑ European Commission, Regulation Youth on the Move: An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union, COM(2010) 477 final, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/education/tools/statistics_en.htm.

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012 (p. 10).

- ↑ European Commission, Early School Leaving (accessed 19 August 2014)

- ↑ European Commission, Tertiary Education (accessed 19 August 2014)

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2013, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2013 (p. 41).

- ↑ For further details on the impact of demographic ageing on the labour force see the article on ‘Employment’.

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012 (p. 10).

- ↑ European Commission, Early School Leaving (accessed 23 July 2013); European Commission (Directorate-General of Education and Culture), Education and Training Monitor 2012, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012 (p. 17).

- ↑ European Commission, Early School Leaving and European Commission, Tertiary Education (accessed 23 July 2013).

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, 2010 (p. 11).