Archive:The EU in the world - population

- Data from February 2014. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: May 2015.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2014 (to be published).

This article focuses on population structure and population developments in the European Union (EU) and in the 15 non-EU countries from the Group of Twenty (G20). It covers key demographic indicators and gives an insight of the EU’s population in comparison with the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

(%) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

(million inhabitants) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Urbanisation Prospects: the 2011 Revision)

(years) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

(men per 100 women) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

(% of total population) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

(% of the population aged 15–64) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (demo_pjangroup) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

(years) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (demo_pjangroup) and the OECD (Pensions at a glance)

(%) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and (demo_pjangroup) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World marriage data 2012)

(births per woman) - Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and (demo_find) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

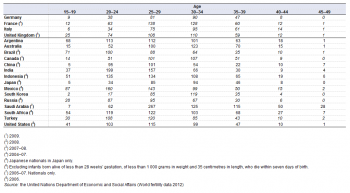

(births per 1 000 women) - Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and (demo_find) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World fertility data 2012)

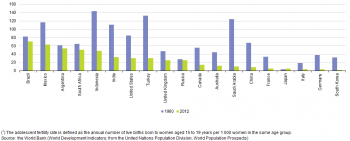

(live births per 1 000 women aged 15–19) - Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and (demo_find) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators; from the United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects)

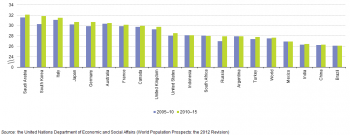

(years) - Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and (demo_find) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

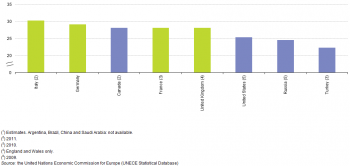

(years) - Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and (demo_find) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE Statistical Database)

(per 1 000 population) - Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2010 Revision)

(1 000 applicants) - Source: Eurostat (migr_asyappctza) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR Statistical Online Population Database)

(% of the population aged 15–64) - Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind), (demo_pjangroup) and (proj_10c2150p), the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

Main statistical findings

Population size and population density

Between 1960 and 2012 the share of the world’s population living in G20 members fell from 73.8 % to 64.5 %

In 2012, the world’s population exceeded 7 000 million inhabitants and continued to grow. Although all members of the G20 recorded higher population levels in 2012 than they did more than 50 years before, between 1960 and 2012 the share of the world’s population living in G20 members fell from 73.8 % to 64.5 %. Russia recorded the smallest overall population increase (19.7 %) during these 52 years, while the fastest population growth among G20 members was recorded in Saudi Arabia, with a near seven-fold increase.

The most populous countries in the world in 2012 were China and India, together accounting for 36.7 % of the world’s population (see Table 1) and 56.9 % of the population in the G20 members. The population of the EU-28 in 2012 was 505.2 million inhabitants, 7.3 % of the world’s total.

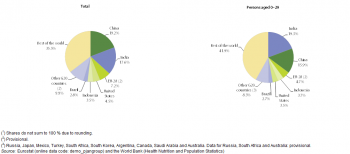

Figure 1 contrasts the population shares of the largest G20 members in the world in terms of total population and an analysis focused on children and youths, in other words, persons less than 30 years old. The G20 share of the world population was smaller when restricted to children and youths, 58.1 % compared with 64.5 % for the whole population. As can be seen from Figure 1, the EU-28, China and the United States had much smaller shares of the world’s population of children and youths, due to the relatively low share of children and youths in their populations (and a relatively high share of older persons); this was also the case for Japan, South Korea, Canada, Russia and Australia as can be seen in Table 2. By contrast, children and youths made up a relatively large proportion of the populations of Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, India and South Africa.

As well as having the largest populations, Asia had the most densely populated G20 members, namely South Korea, India and Japan — each with more than 300 inhabitants per km², followed by China and Indonesia. The EU-28 followed with more than 100 inhabitants per km².

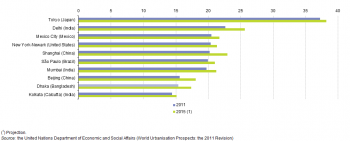

All but one of the 10 largest urban agglomerations in the world in 2011 were in G20 members, with Dhaka (Bangladesh) the only exception — see Figure 2. Including Dhaka, 7 of the10 largest urban agglomerations were in Asia, with Mexico City, New York-Newark (United States) and São Paulo (Brazil) completing the list. Based on United Nations’ projections, Shanghai will be the third largest city in the world by 2015, while Mumbai (Bombay) will overtake São Paulo to move into sixth place. Furthermore, by 2015 Karachi in Pakistan will move into the top 10, displacing Kolkata (Calcutta). Worldwide, there were more than 630 urban agglomerations with a population in excess of 750 000 inhabitants in 2011 and together their aggregated population of 1.5 billion people was equivalent to just over one fifth of the world’s population; 46 of these agglomerations were in the EU-28.

Population structure, marriages and divorces

The median age of the world’s population is projected to reach 29.6 years by 2015

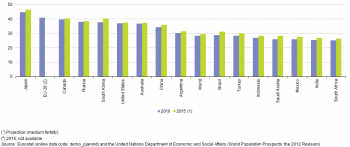

The median age of the world’s population in 2010 was 28.5 years and this is projected by the United Nations to reach 29.6 years by 2015. In China, Australia, the United States, South Korea and Russia the median age was at least five years higher in 2010 than the world average, while in Canada and the EU-28 the median age was more than 10 years higher and in Japan it was more than 15 years above the world average — see Figure 3. In all G20 members, the median age is projected to increase between 2010 and 2015, most notably in South Korea, Saudi Arabia and Brazil, where increases in excess of 2 years are expected. More information on the age structures of G20 members is presented in Table 2, while some of the factors influencing this structure are presented in the rest of this article and the article on Health, for example, fertility and migration and life expectancy.

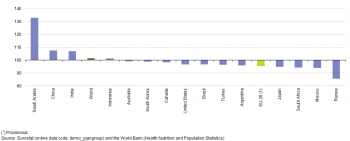

In the majority of G20 members the number of men and women in the population is relatively balanced, although women often account for a slight majority of the population reflecting among other factors women’s higher life expectancy. The number of men per 100 women ranged from 85.7 in Russia to 133.0 in Saudi Arabia in 2012. Within this range, there were 101.6 men per 100 women across the whole of the world and 95.3 men per 100 women in the EU-28 (see Figure 4). The particularly high ratio of men to women in Saudi Arabia was concentrated in the adult working-age population (aged 15–64 years), with ratios more balanced for persons aged less than 15 or 65 and over; as such, the overall imbalance may reflect, in part, a gender imbalance among immigrants that have fuelled a rapid increase in population levels during recent decades.

Ageing society represents a major demographic challenge for many economies and may be linked to a range of issues, including, persistently low levels of fertility rates and significant increases in life expectancy during recent decades.

Figure 5 shows how different the age structure of the EU-28’s population is from the average for the whole world. Most notably the largest shares of the world’s population are among the youngest age classes, reflecting a population structure that is younger, whereas for the EU-28 the share of the age groups below those aged 40–44 years gets progressively smaller approaching the youngest cohorts, reflecting falling fertility rates over several decades and the impact of the baby-boomer cohorts on the population structure (resulting from high fertility rates in several European countries up to the mid-1960s). Another notable difference is the greater gender imbalance within the EU-28 among older age groups than is typical for the world as a whole.

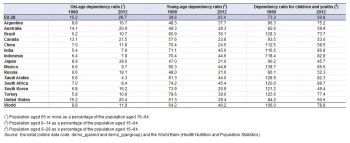

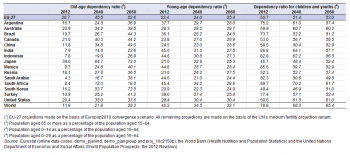

The young and old age dependency ratios shown in Table 3 summarise the level of support for younger persons (aged less than 15 years) and older persons (aged 65 years and over) provided by the working-age population (those aged 15–64 years). The fall in the young-age dependency ratio for the EU-28 between 1960 and 2012 more than cancelled out an increase in the old-age dependency ratio. Most of the G20 members displayed a similar pattern, with two exceptions: in Japan the increase in the old-age dependency ratio exceeded the fall in the young-age dependency ratio; in Saudi Arabia both the young and old-age dependency ratios were lower in 2012 than in 1960, reflecting a large increase in the working-age population in this country. The third dependency ratio shown in Table 3 is the ratio between children and youths (persons aged less than 30 years) and the working-age population. In 2012, this ratio exceeded 50 % in all G20 members except for Japan and South Korea and exceeded 80 % in Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Mexico, India and South Africa.

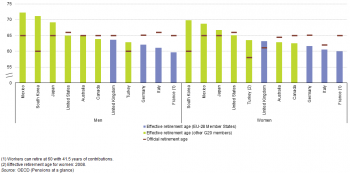

One of the many issues related to ageing populations is the expected increase in the burden for pension payments. Many industrialised countries are in the process of progressively increasing their official retirement ages (especially for women). Figure 6 compares the effective and official retirement ages for men and women in a number of G20 members in 2012. For men the effective retirement age ranged from 59.7 years in France to 71.1 years in South Korea and 72.3 years in Mexico, while for women the same countries were at each end of the age range, 60.0 years in France to 68.7 years in Mexico and 69.8 years in South Korea. A majority of G20 members reported lower effective than official retirement ages, although there were several exceptions: in South Korea, Japan, Mexico and Turkey the effective retirement age was above the official retirement age for both men and women, while this was also the case in the United Kingdom for women.

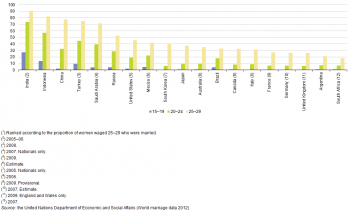

Indicators for marriage provide information in relation to family formation. Marriage, as recognised by the law of each country, has long been considered as marking the formation of a family unit. While marriage rates are generally presented relative to 1 000 members of overall population the analysis by age group for 2010 shown in Figure 7 indicates the proportion of women from each age group that are married. Generally less than 5 % of women aged 14–19 in G20 members were married, with Turkey, Indonesia and India exceptions; in all four EU G20 members this proportion was less than 0.5 %. Among women aged 20–24, the share who were married was considerably higher than for 15–19 year old women, ranging from 6.2 % in South Korea to 39.2 % in Saudi Arabia, with the same three countries — Turkey, Indonesia and India — above this range. More than two thirds of women aged 25–29 in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, China, Indonesia and India were married in contrast to less than one third in Brazil, Canada and the four EU G20 members and less than one quarter in Argentina and South Africa.

Natural population change

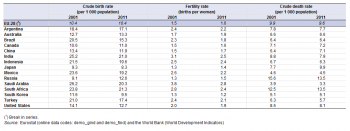

The crude birth rate in the EU-28 among the lowest across the G20 members

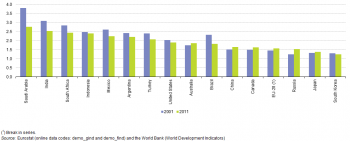

Fertility rates in industrialised countries have fallen substantially over several decades. The rates fell between 2001 and 2011 in more than half of the G20 members, most notably in Saudi Arabia, India and Brazil. Only Russia recorded an increase of more than 0.1 births per woman during this period. The average fertility rate in the EU-28 in 2011 was 1.6 births per woman, lower than in all of the other G20 members except Russia, Japan and South Korea.

Table 4 presents an analysis of fertility rates for women aged 15–49 in 2010: these rates are expressed in terms of birth per 1 000 women within that age group. In three of the four EU G20 members (France was the exception), fertility rates peaked in the 30–34 age group; this was also the case in Australia, Canada, Japan and South Korea. In France, the peak for the fertility rate was recorded for the age group 25–29; this was also the case in China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey and the United States. In the remaining five G20 members, the highest fertility rates were recorded earlier in women’s lives, among those in the age group 20–24. In most G20 members, women having reached the age group 45–49 had relatively low fertility rates, with only Saudi Arabia and China reporting higher fertility rates in this age group than for the age group 15–19. Figure 9 presents data for the same fertility indicator, focusing on the youngest age group, namely those women aged 15–19: the data source is different but provides somewhat fresher data, namely for 2012, which is compared with 1960. The 2012 data shows relatively low fertility rates in this age group for three of the four EU G20 members (the United Kingdom was the exception) as well as Japan and South Korea; the rate for the United Kingdom was closer to that for Russia. All G20 members reported falling fertility rates for this age group between 1960 and 2012, most notably in Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Turkey.

Falling fertility rates have been accompanied by a postponement of motherhood, which may in part be attributed to increases in the average length of education of women, increased female employment rates, as well as changes in attitudes towards the position of women within society and the roles of men and women within families. Figure 10 shows a range in the average age of women at childbearing in the period 2010–15, from 26.2 years in Brazil to 32.1 years in Saudi Arabia. The mean age at childbearing increased in most G20 members between 2005–10 and 2010–15; the exceptions were Argentina, Indonesia and Mexico where it remained stable and South Africa where it fell slightly.

Figure 11 focuses on the average age of women at the time of the birth of their first child. Although the years for which data are available are not strictly comparable between Figures 10 and 11, it can be noted that the average age at the time of the birth of a woman’s first child was considerably lower than the overall average age for childbirth in Turkey and to a lesser extent in Russia and the United States, while in the four EU Member States for which data are shown the differences were much smaller.

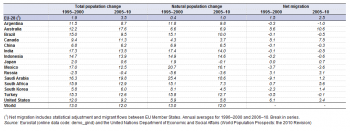

There are two distinct components of population change: the natural change that results from the difference between the number of live births and the number of deaths; and the net effect of migration, in other words, the balance between people coming into and people leaving a territory. The following tables and figures look at several indicators related to births, deaths and migration and their impact on the overall level of population. The crude birth rate in the EU-28 in 2011 was unchanged when compared with 2001 and remained among the lowest across the G20 members, with only South Korea and Japan recording lower birth rates. Crude birth rates recorded in India and South Africa in 2011 were more than double the average rate for the EU-28.

When the death rate exceeds the birth rate there is negative natural population change; this situation was experienced in Russia and Japan in 2011. The reverse situation, natural population growth due to a higher birth rate, was observed for all of the remaining G20 members (see Tables 5 and 6) with the largest differences recorded in Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Indonesia and India. Russia and South Africa recorded the highest crude death rates, in the latter case reflecting in part an HIV/AIDS epidemic which has resulted in a high number of deaths among relatively young persons, such that that the difference between crude birth and death rates in South Africa was not large despite the high birth rate.

Migration and asylum

An increase in the population numbers in almost all G20 members

The combined effect of natural population change and net migration including statistical adjustment (which refers to changes observed in the population figures which cannot be attributed to births, deaths, immigration or emigration) can be seen in the total change in population levels. During the five years between 2005 and 2010 all of the G20 members, except Russia, experienced an increase in their population numbers. Russia’s declining population resulted from net inward migration being smaller than the negative natural population change. Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico and Turkey experienced negative net migration that was less than the positive increase from natural population change. The EU-28, Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and the United States experienced the cumulative effects of positive natural population change and net migration. This situation was broadly similar to that observed 10 years earlier, between 1995 and 2000, with the notable exception of Saudi Arabia which had then experienced relatively strong outward net migration in contrast to the more recent pattern for net inward migration, although in 1995–2000 this was outweighed by higher natural population growth.

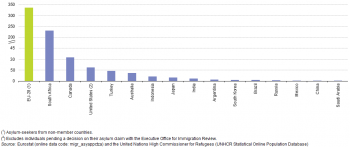

In 2012, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported that there were 928 200 asylum applicants across the world, of which 335 300 (from non-member countries) were in the EU-28. Among those seeking asylum in the EU-28, a relatively high proportion of applicants were from Afghanistan, Russia, Syria, Pakistan, Serbia, Somalia, Iran, Iraq, Georgia and Kosovo (each accounting for between 28 000 and 10 000 asylum seekers). The highest numbers of asylum applicants into the EU-28 from G20 countries came from Russia (24 290), Turkey (6 210) and China (5 185); note, the latter figure includes applicants from Hong Kong. Figure 12 shows that aside from the EU-28, there were relatively high numbers of asylum seekers in 2012 in South Africa (many of whom originated from Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo) and to a lesser extent in Canada; note that the figures for the United States exclude individuals pending a decision on their asylum claim.

Future population: population projections

The number of the world’s inhabitants projected to reach almost 10 000 million by 2060

The latest United Nations population projections suggest that the pace at which the world’s population is expanding will slow in the coming decades; however, the total number of inhabitants is projected to reach 9 960 million by 2060, representing an overall increase of 41.3 % compared with 2012. This slowdown in population growth will be particularly evident for developed and emerging economies as the number of inhabitants within the G20 — excluding the EU — is projected to increase by 16.0 % between 2012 and 2060 while the EU-27’s population is projected (by Eurostat) to increase by 3.3 % over the same period. The population of many developing countries, in particular, those in Africa, is likely to continue growing at a rapid pace. Among the G20 members, the fastest population growth between 2012 and 2060 is projected to be in Australia and Saudi Arabia, while the populations of Russia, Japan, China and South Korea are projected to be smaller by 2060 than they were in 2012. Despite the projection of rapid population growth, Australia is expected to remain the least densely populated G20 member through until 2060 when it will draw level with Canada.

Old-age dependency ratios are projected to continue to rise in all G20 members, suggesting that there will be an increasing burden to provide for social expenditure related to population ageing (for example, for pensions, healthcare and institutional care). The EU-27’s old-age dependency ratio is projected to nearly double from 26.7 % in 2012 to 52.6 % by 2060, when it is forecast to be 24.2 percentage points above the world average, but considerably lower than in South Korea or Japan. With relatively low fertility rates the young-age dependency ratio is projected to be lower in 2060 than it was in 2010 in several G20 members, dropping by more than 10.0 percentage points in Saudi Arabia, Mexico, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey and Brazil. Projected increases for this ratio are relatively small, reaching 5.9 percentage points in Russia. In the EU-27 the young-age dependency ratio is projected to increase from 23.4 % in 2012 to 25.4 % by 2060, but will remain well below the world average of 33.1 %. A similar situation can be observed for the dependency ratio for children and youths, with rates dropping between 2012 and 2060 by more than 20.0 percentage points in Mexico, Saudi Arabia, India, South Africa, Indonesia, Turkey and Brazil. The largest increase is projected for Japan (up 6.7 percentage points), while the increase projected for the EU-27 is somewhat lower (up 2.2 percentage points), again leaving the rate in the EU-27 in 2060 (53.0 %) below the world average (65.4 %).

Data sources and availability

The statistical data in this article were extracted during February 2014. The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes global — standards. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU data

Most of the indicators presented for the EU have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this publication and data that is subsequently downloaded.

G20 countries from the rest of the world

For the 15 G20 countries that are not members of the EU, the data presented have generally been extracted from a range of international sources, most notably the World Bank, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. For some of the indicators shown a range of international statistical sources are available, each with their own policies and practices concerning data management (for example, concerning data validation, correction of errors, estimation of missing data, and frequency of updating). In general, attempts have been made to use only one source for each indicator in order to provide a comparable analysis between the countries.

Context

As a population grows or contracts its structure changes. In many developed economies the population’s age structure has become older as post-war baby-boom generations reach retirement age. Furthermore, many countries have experienced a general increase in life expectancy combined with a fall in fertility, in some cases to a level below that necessary to keep the size of the population constant in the absence of migration. If sustained over a lengthy period, these changes can pose considerable challenges associated with an ageing society which impact on a range of policy areas, including labour markets, pensions and the provision of healthcare, housing and social services.

In its 2009 Communication of an EU Strategy for Youth — Investing and Empowering, the European Commission states that ‘Youth are a priority of the European Union’s social vision’ and that ‘Young people are not a burdensome responsibility but a critical resource to society which can be mobilised to achieve higher social goals’. This article includes a selection of indicators related to children and youths: later in 2014, Eurostat plans to release a flagship publication on children and youths in the EU.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Demographic outlook 2010

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Pocketbook on Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2013 edition

- The EU in the world 2013

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the African Union — 2013 edition

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

Main tables

- Population (t_populat), see:

- Demography (t_pop)

- Demography - National data (t_demo)

- Population (t_demo_pop)

- Population density (tps00003)

- Population (t_demo_pop)

- Demography - National data (t_demo)

Database

- Population (populat), see:

- Demography (pop)

- Demography - National data (demo)

- Demographic balance and crude rates (demo_gind)

- Population (demo_pop)

- Population on 1 January by age and sex (demo_pjan)

- Population on 1 January by five years age groups and sex (demo_pjangroup)

- Population on 1 January: Structure indicators (demo_pjanind)

- Fertility (demo_fer)

- Fertility indicators (demo_find)

- Marriage and divorce (demo_nup)

- Marriage indicators (demo_nind)

- Divorce indicators (demo_ndivind)

- Demography - National data (demo)

- International Migration and Asylum (migr)

- Asylum (migr_asy)

- Applications (migr_asyapp)

- Asylum and new asylum applicants by citizenship, age and sex Annual aggregated data (rounded) (migr_asyappctza)

- Applications (migr_asyapp)

- Asylum (migr_asy)

- Population projections (proj)

- EUROPOP2013 - Population projections at national level (proj_13n)

- Projected population (proj_13np)

- EUROPOP2013 - Population projections at national level (proj_13n)

Dedicated section

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

External links

- Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations FAO

- OECD

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe UNECE

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR

- World Bank