This Statistics Explained article has been archived - for recent articles on national accounts and GDP see here.

- Data from September 2009, most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Database.

National accounts provide useful indicators for business cycle analysis. This article aims to demonstrate how European Union (EU) national accounts data can be used to monitor and analyse the recent evolution of the business cycle – for example, focusing on the economic and financial crisis.

It starts with a presentation of the main GDP aggregate, before an analysis of external trade, output, income, consumption and investment, as well as developments for savings and wealth (from the sector accounts). Other economic indicators, such as economic sentiment, inflation and unemployment, complement information derived from national accounts.

The indicators presented focus on economic developments over a period of close to ten years and, more specifically, on the impact of the financial and economic crisis (as shown by the most recent data available at the time of writing). This section concludes with a point in relation to statistical implications of the financial and economic crisis.

Impact on main national accounts aggregates

Quarterly national accounts indicators presented in this section show the considerable impact of the economic and financial crisis.

Focussing mainly on aggregated data for the EU-27 economy, but presenting also some snapshots in relation to the most recent situation observed in the Member States, the data presented in this section drawn from national accounts illustrate how the economic and financial crisis has impacted upon various sectors of the economy.

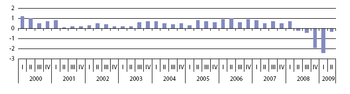

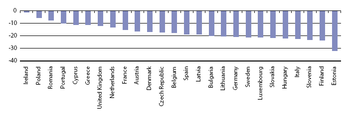

GDP growth

Taking a medium-term perspective, Figure 1 shows quarter on quarter changes in GDP since 2000 for the EU-27. While positive growth rates were recorded each and every quarter until the middle of 2008, the negative growth rates in the final quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009 were greater in magnitude than any of the growth rates recorded in earlier years, underlying the severity of the recession. In fact these were the first negative rates of change since the series began in 1995 and it is widely acknowledged that this is the worst global recession since the 1930’s. The most recent rates of change available show that the strength of the recession weakened during 2009 and estimates for the third quarter of 2009 show a return to growth in the EU-27 as a whole. However, the economic downturn was not homogeneous across the EU. Looking at the changes in GDP volumes compared with one year earlier, Figure 8 shows the great diversity in the intensity of the economic downturn between Member States: while the Baltic Member States all experienced particularly strong negative rates of change, Poland still continued to record economic growth.

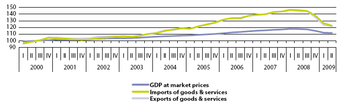

External trade

The global dimension of the economic crisis is clearly demonstrated by the evolution of external trade. Figure 2 illustrates that external trade in goods and services grew faster than GDP in the EU-27 from 2002 to the beginning of 2008. From this date, reductions in levels of external trade were more pronounced than the contraction in GDP. Furthermore, the level of GDP appeared to be stabilising in the middle of 2009, whereas external trade flows were still falling, albeit at a slower rate than in the second half of 2008.

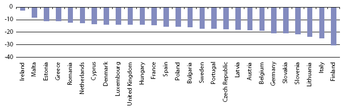

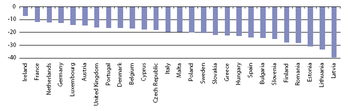

Figures 4 and 3 show that the relative importance of imports and exports varies significantly across countries, and that the drop in imports was generally slightly more significant than the drop experienced for exports during the second quarter of 2009.

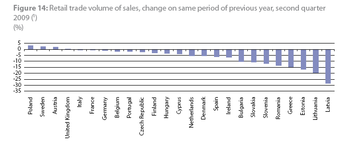

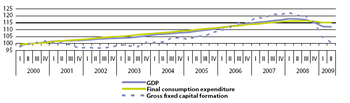

Production, consumption and investment

The contraction in international trade may be cited as one of the main reasons for falling demand within the global economy. Industrial output in the EU-27 dropped sharply from the beginning of 2008. Figure 5 shows that the decline in industrial output was also much sharper than that recorded for GDP (industrial output fell by around 18 % overall from the first quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2009). The decline in retail sales was more modest, but in both cases, there were again significant variations across Member States (see Figures 6 and 7).

An analysis of expenditure (see Figure 8) confirms that the decline in final consumption expenditure (mainly of households and government) was relatively modest in comparison, but investment (shown as gross fixed capital formation) declined at a particularly rapid pace across the EU during the recession.

Impact on European sector accounts

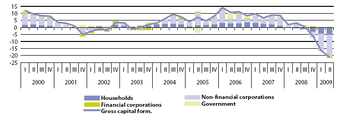

More detailed insights on trends affecting different types of economic agents during the recession can be gained from the sector accounts. Figures 9 to 11 indicate the contribution of the institutional sectors to changes in value added, capital formation, and lending/borrowing.

Non-financial corporations generally deliver the largest contribution to value added (and GDP) growth, but their contribution is quite volatile. The contribution of households normally fluctuates less, partly because of the stabilising influence of the imputed rent on owner-occupied dwellings. Nevertheless, during recession in 2008/2009 the contribution of households to value added growth fell, and in fact turned negative from the final quarter of 2008.

Gross capital formation includes principally investment in fixed assets (buildings, machinery) but also changes in inventories. The overall growth of gross capital formation is mainly driven by developments in the non-financial corporations sector and, to a lesser extent, by households (dwellings). Gross capital formation is relatively volatile in all sectors, and during the recession in 2008/2009 households and non-financial corporations recorded negative rates of change for this indicator.

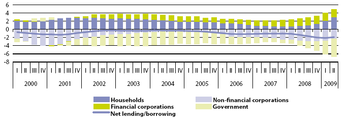

The difference between savings plus net capital transfers, on the one hand, and gross capital formation, on the other hand, is net lending if positive or net borrowing if negative. During the period shown in Figure 18 the EU-27 has been a net borrower from the rest of the world, and the extent of this borrowing increased from the beginning of 2005. Over the period shown, households were net lenders as were financial corporations in most quarters (note that the figure in fact shows cumulated values for four quarters), while non-financial corporations were net borrowers, as were governments most quarters. The increase in net borrowing during the recession in 2008/2009 results in large part from particularly strong growth in government net borrowing.

The remainder of this section reviews developments in the corporate, household or government sectors, focussing mainly on wealth effects.

Corporations

The net financial wealth of corporations is the ultimate property of the owners/ shareholders of corporations, mainly households. As such it is useful to analyse this before accounting for shares and other equity on the liabilities side. Figures 12 and 13 show the rate of change of net financial wealth adjusted in this way for financial and non-financial corporations, along with the changes in the main components.

As for household financial wealth (see below), in recent periods other changes in prices and volumes have moved from positive to negative rates of change. Figure 14 analyses the net financial wealth of non financial corporations both on the assets and liabilities side, and confirms that the main movement in net financial wealth was changes in the value of shares and other equity.

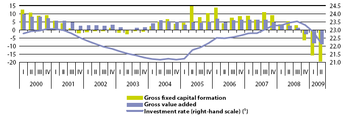

Whereas for households the investment rate is expressed relative to disposable income, for non-financial corporations it is expressed relative to value added. Figure 15 indicates how the investment rate in the EU-27 increased between 2004 and the middle of 2008 as the growth of gross fixed capital formation outstripped that of value added. This situation was subsequently reversed with relatively large negative rates of change recorded for gross fixed capital formation from the final quarter of 2008.

Households

The main contribution to households’ income growth is provided by the compensation of employees, while operating surplus and mixed income (which accrues to self-employed households and home owners) generally has the next highest contribution. Both of these sources recorded negative rates of change during the recession, most notably in the first two quarters of 2009. Net property income (interest received minus interest paid, dividends, etc) and net social benefits are normally the most volatile components; the latter is also affected by the position in the business cycle and its growth was particularly large in the first two quarters of 2009.

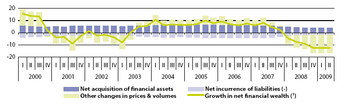

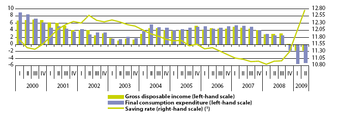

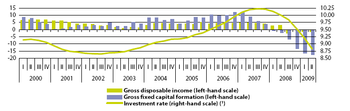

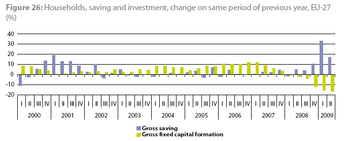

If households’ gross disposable income increases faster than their consumption the household saving rate increases, and this has been observed in the EU-27 since the middle of 2008 – see Figure 16 – with consumption expenditure actually falling in the final quarter of 2008 and the first half of 2009. The saving rate is a key indicator for the household sector: short-term increases in the household saving rate are often linked with pessimistic expectations about the economic future, while longer term variations are generally driven by changes in the labour market or interest rates movements. Household savings (and also borrowing) may be used to finance investment in fixed assets (see Figure 17). When households’ gross disposable income grows slower than their investment in fixed assets (principally dwellings) the investment rate increases: this occurred between 2003 and 2007 in the EU-27, with the reverse situation in 2008 and the first half of 2009. Figure 18 summarises the development of the rate of change of households’ savings and investment within the EU-27, with the level of saving increasing significantly accompanied by a fall in investment in the most recent quarters.

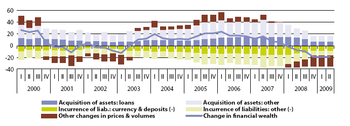

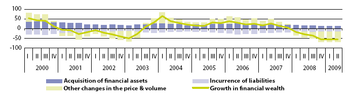

The households sector has the greatest wealth of all sectors, composed of residential property as well as other non-financial and financial assets. Focusing on financial wealth, changes in the net financial wealth of households are influenced to some extent by their net acquisitions of financial assets and their net incurrence of liabilities, for example, loans for property purchases. Furthermore, changes in the price of households’ financial assets (notably changes in share prices) play an important part in the overall change in net financial wealth: in the euro area this net financial wealth fell throughout 2008 and the first half of 2009 (see Figure 19), driven by falls in the value of their assets.

Governments

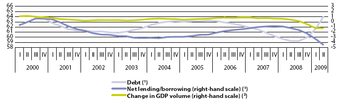

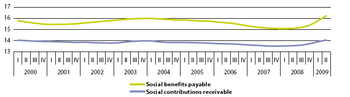

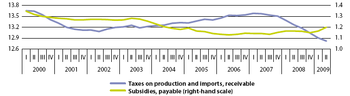

Government borrowing and debt within the EU-27 increased strongly during 2008 and the beginning of 2009 as governments responded to the economic and financial crisis – see Figure 20. Figure 21 presents the development of net lending/borrowing (right axis) as well as an analysis of the main categories of receipts and payments of the government sector (left axis). The receipt side records taxes less subsidies on production and current taxes on income and wealth. The payment side records notably compensation paid to government employees andsocial contributions less benefits that account for the surplus/deficit of the social security system (including public pension schemes). During 2008 and 2009 net borrowing by governments in the EU-27 increased, largely because net revenue from production taxes less subsidies fell and net payments for social security increased along with other payments. Figure 22 shows the separate figures for contributions receivable and benefits payable from social security systems: as a share of GDP both of these increased during 2008 and 2009, with benefits payable growing faster. Figure 23 provides a similar analysis for taxes on production and imports and subsidies: despite falling GDP, taxes on production and imports as a share of GDP fell from 2007, while subsidies were relatively stable.

Statistical implications of the financial and economic crisis

The financial and economic crisis generated a number of challenges for statisticians. Statisticians working in national statistical institutes, European institutions, and international organisations have been confronted with an increased number of requests from economic actors and policymakers to improve the provision of relevant statistical indicators in a timely and reliable fashion. The worldwide nature of the crisis underlined the global dimension of economic and financial phenomena, the integration of financial markets, and the rapidity of circulation of information. This has resulted in calls for a thorough assessment of the role that official statistics played in the period up to the beginning of the crisis, and the role that statistics will play in the future.

Reactions of the European statistical system

The reaction of statistical authorities was placed under scrutiny, while the capacity of these authorities to face the challenges of the crisis was also examined. The European statistical system (ESS) acknowledged such challenges and promptly reacted to meet new and urgent demands both at a national level, an EU level, and at a global level.

The exceptional evolution of the financial markets and its consequences on the real economy required the ESS to deliver a prompt and coherent reaction, addressing in particular the following dimensions:

- statistical consequences on key selected statistical domains with special relevance at a European level for administrative purposes (for example, the appropriate recording of bank and other market rescue operations in the context of public finance);

- prompt availability of key short-term economic indicators for monitoring the impact of the crisis and the impact of measures to offset it;

- international coordination;

- enhanced communication at different levels among users and stakeholders.

The ESS’s reaction to the crisis had, therefore, to be multi-faceted and its overall framework for action was fixed around three axes:

- the ESS action plan on the accounting consequences of the financial crisis;

- the regular production of key shortterm economic indicators;

- a critical analysis of methodological and practical aspects relating to the statistical production process.

Accounting consequences in the area of public finance

One key aspect of the ESS’s reaction has been to ensure the appropriate and proper consideration of the statistical consequences of the financial crisis on key statistics used in the EU for administrative purposes and for the assessment of public finance.

As the financial crisis escalated from late summer 2008, governments and central banks in European countries intervened through various operations in an effort to restore confidence in the financial system, at first to rescue individual financial institutions in distress, and then through coordinated interventions broadly targeting financial institutions regardless of whether they were in distress or not, recognising the systemic aspect of the situation.

All these operations required an appropriate recording and treatment in statistical terms, notably in the framework of public finance statistics. A key requirement for the ESS in this area was to ensure the consistency across time and across countries of the statistical treatment of public interventions in full respect of the ESA95 rules.

The ESS action plan on the accounting consequences of the financial crisis was created and implemented to achieve this target and to support it by strengthening coordination among European statistical authorities, while also enhancing communication with users and stakeholders.

In this sense, the activation of the ESS action plan:

- streamlined the reaction of the ESS to the financial crisis;

- created awareness of the statistical consequences;

- strengthened coordination and communication;

- supported ESS actions to handle the response to the crisis.

The recording and treatment in national accounts of public interventions has clearly been the key methodological topic for official statisticians. In this field, Eurostat, in cooperation with ESS partners, has closely monitored the public interventions and their implications for national accounts data, notably for the government deficit and debt statistics used for the excessive deficit procedure (EDP).

The outcome of this methodological analysis provided the background information for defining the methodological treatment in national accounts, of these types of operations. On 15 July 2009, Eurostat published a decision on ‘the statistical recording of public interventions to support financial institutions and financial markets during the financial crisis’ .

International cooperation

In addition, the worldwide nature of the crisis highlighted some limits of official statistics (international comparability, timeliness, and specific indicators in key areas – for example, the housing market).

The response of international official statisticians was threefold:

- enhancing the communication of available statistics;

- starting an in-depth analysis to identify the ideal statistical tools for policymakers/ analysts/economic operators;

- enhancing the international comparability of key indicators.

Two initiatives are particularly important in this area:

- the work of the inter-agency group on economic and financial statistics – IAG (IMF, BIS, Eurostat, ECB, World Bank, UNSC) on the statistical consequences of the financial and economic crisis;

- seminars a set of three international jointly organised by United Nations Statistical Division, Eurostat and some national statistical institutes; two of these seminars already took place;

The first of these was an international seminar on timeliness, methodology and comparability of rapid estimates of economic trends jointly organised by Statistics Canada, UNSD and Eurostat, held in Ottawa in May 2009 (12) and the second was an international seminar on early warning and business cycle indicators jointly organised by the CBS, UNSD and Eurostat, held in Scheveningen (the Netherlands) in December 2009 (13). Both of these groups focused their efforts on trying to identify which official economic and financial indicators should be regularly produced by national statistical authorities to monitor the evolution of the economy. The Interagency Group set up the ‘Principal Global Indicators’ website, offering the available indicators regularly collected by international agencies for different countries and in different relevant statistical domains.

The work of all these groups will be used to help prepare answers to the requirements expressed by the G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors with respect to statistics in relation to the financial and economic crisis.

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Eurostat Yearbook 2010; In the spotlight – national accounts

- EU economic data pocketbook – quarterly

Main tables

- Annual national accounts (t_nama)

- Quarterly national accounts (t_namq)

- Annual sector accounts (t_nasa)

Database

- Annual national accounts (nama)

- Quarterly national accounts (namq)

- Annual sector accounts (nasa)

- Quarterly sector accounts (nasq)

- Supply, use and Input-output tables (naio)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Annual national accounts (ESMS metadata file - nama_esms)

- Annual sector accounts (ESMS metadata file - nasa_esms)

- Quarterly national accounts (ESMS metadata file - namq_esms)

- Quarterly sector accounts (ESMS metadata file - nasq_esms)

- Supply, use and Input-output tables (ESMS metadata file - naio_esms)

Other information

- European system of accounts ESA 1995

- Eurostat-OECD methodological manual on purchasing power parities

- Handbook on quarterly national accounts

- Handbook on price and volume measures in national accounts

- NACE Rev. 1 – statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community

External links

- United Nations - Statistics Division - System of National Accounts 2008 - 2008 SNA

- United Nations Statistics Division 1993 SNA