Archive:Labour market slack - unmet need for employment - quarterly statistics

Data extracted in July 2020

Planned article update: October 2020

Highlights

The health crisis due to the Covid-19 has become in the European Union, like in other parts of the world, an economic crisis. It is highly expected and, even, already observed, that the outcomes of the economic storm impact significantly the EU-27 labour market.

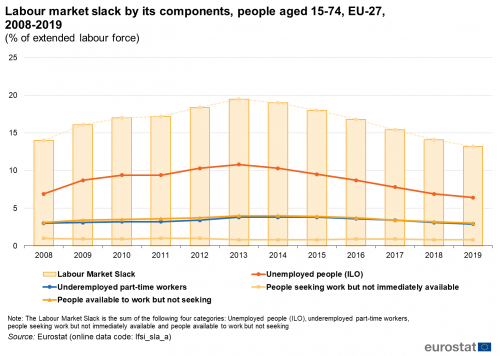

Concretely, given the lock-down and the impending recession, some people may have lost their job or the opportunity to start a new one. In addition, people who were previously considered unemployed by fulfilling the ILO requirement of looking for work might have given up their search for a certain period of time due to the poor economic prospects or the shut-down of the enterprises' activity moving them outside the labour force. It is therefore assumed that beyond unemployment, more jobless people either inside or outside the labour force may have an unmet need for employment. This whole potential demand for employment (the unemployed and the supplementary categories) constitute the labour market slack.

This article based on quarterly LFS data investigates the impacts of the crisis on unemployed people as well as on other people constituting also the labour market slack. These supplementary categories consist of underemployed people, those part-time workers who wish to work more, and of people who might be associated to the labour force, because of their availability to work or their work search, but who are not recorded as such. The last category is called the potential additional labour force.

Both European and country approach are taken in this article. It aims at showing the effects of the crisis at the global level, in the European Union (EU) and at the national level, in the respective [Glossary:EU_Member_States|Member States]].

One should note that this article uses the seasonal adjusted data from the first quarter of 2020 i.e. January-March (2020Q1) and compares it to the last quarter of 2019 (2019Q4). It is highly expected that the consequences of the Covid crisis on the labour market will be more visible in the second quarter of 2020 data (April-June) that should be available in September.

Full article

Labour market slack in the EU-27

Increase in the labour market slack in the extended labour force in two thirds of the Member States

As aforementioned, the Labour market slack refers to all unmet needs for employment, including unemployed people according to the ILO definition as well as the underemployed part-time workers and people available to work but not seeking and people seeking but not available. People in these last two categories are outside the labour force. To make coherent the inclusion of these supplementary categories, the labour force is incremented by these two categories and gives as result, the so-called "extended labour force". It allows using the Labour market slack as a share of the extended labour force and comparing all components also expressed in percent of the extended labour force.

At the European level, people with a unmet need of employment accounted during the first quarter 2020 for 13.3 % of the extended labour force as shown in Figure 1. The slack was more pronounced for women who stands at 15.6 % than for men 11.3 %. Among EU Member States, Greece, Spain and Italy recorded the highest slacks reaching more than one fifth of the extended labour force (23.1 %, 22.6 % and 21.3 % respectively.Those countries also recorded the biggest gender gaps between women and men: 28.8 % for men against 18.6 % for men in Greece, 27.6 % against 18.1 % in Spain and 26.3 % against 17.2 in Italy. Only in three EU Member States, namely, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania, the Labour market Slack of men exceeded the one of women but by less than 2 p.p. The lowest labour slacks in the EU-27 were observed in Malta, Poland and Czechia with less than 6 % of the extended labour force facing an unmet demand for employment with slacks corresponding respectively to 5.9 %, 5.7 % and 2.9 % of the extended labour force.

The development of the labour market slack from the last quarter 2019 to the first one 2020 might reflect the consequences of the health crisis. Based on the LFS data, the Labour market slack increased by 0.4 p.p. during the first quarter at the European level, from 12.9 % to 13.3 %. This is the first time it increased since the first quarter 2013 as it can be seen in the dynamic tool at the top of the article. In the same vein, the Labour market slack grew in exactly two thirds of the EU countries but decreased in nine countries. Among the EU Member States, Latvia, Germany and Luxembourg recorded the greatest increases as easily observed based on the second graph of Figure 1. In Latvia, the Labour market slack rose in the first quarter of 2020 from 11.8 % to 13.9 % of the extended labour force (+2.1p.p.), in Germany from 7.5 % to 9.4 % (+1.9p.p) and in Luxembourg from 11.4 to 13.0 (+1.6p.p). The biggest decreases recorded among EU countries accounted for less than 1p.p. and were registered in Greece (-0.6p.p.), Netherlands, France and in Belgium (all three by -0.4p.p.)

At the European level, women registered an increase of the slack slightly higher than men in percentage of the extended labour force (+0.5p.p. for women and +0.4p.p. for men). However, in Germany the Labour market slack progressed much more noticeably for women (+2.4p.p) than for men (+1.4p.p.). However, the biggest gender- based differences showed a greater increase in the male Labour market slack than in the female one: Estonia such

(% of extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_a)

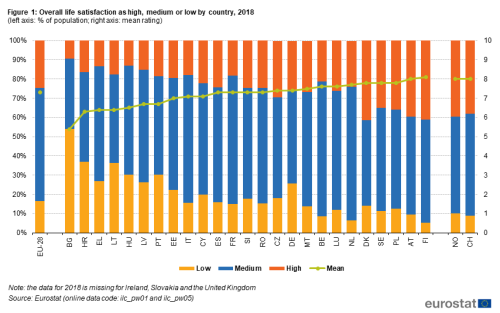

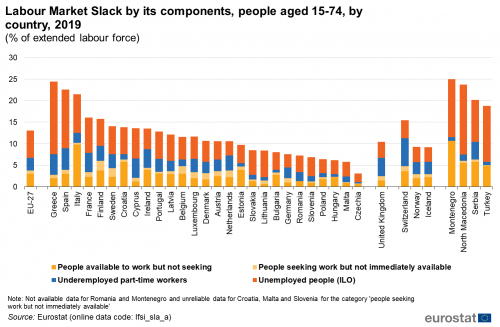

In 2019, the labour market slack was the highest in Greece (24.5 %), Spain (22.7 %), Italy (21.5 %), France (16.1 %) and Finland (15.8 %), all above 15 % of the extended labour force (see Figure 7). Once again, the link between having a high labour market slack and a high unemployment rate is partially verified as the highest unemployment rates in the EU-27 in percentage of the extended labour force are also found in Greece (16.8 %), Spain (13.6 %), Italy (9.0 %), France (8.2 %). Finland ranked 7th with an unemployment rate of 6.3 %.

However, the weight of unemployment in the total labour market slack varies from one country to another, leaving the other components (like the underemployed people, people available for work but not seeking it and those seeking work but not immediately available) relatively more substantial. In 2019, in the Netherlands, Ireland and Finland, unemployment consisted of less than 40 % of the total slack while the three supplementary indicators accounted for more than 60 %. Unemployment stood for 31.0 % of the total labour market slack in the Netherlands, 35.4 % in Ireland and 39.9 % in Finland. In the EU-27, almost half of the slack, 48.9 %, consisted of unemployed people. On the opposite end, in Lithuania, Greece and Slovakia, unemployment accounted for more than two thirds of the total labour market slack.

(% of extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_a)

Focus on unemployment

</sesection> <sesection>

Focus on underemployed part-time workers

More underemployed part-time workers in Spain and Greece, few in Czechia, Hungary and Bulgaria

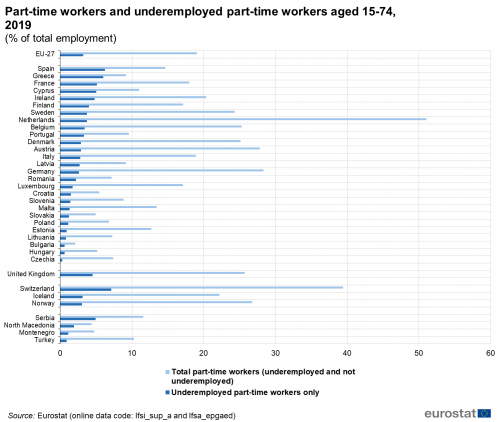

Figure 2 shows the share of employed persons in each country that were part-time workers in 2019 as well as the share of employed people who were underemployed part-time workers. At European level, 3.2 % of the total employment consisted of underemployed people. Underemployment in the EU-27 was highest in Spain (6.2 % of total working persons), followed by Greece (6.0 %), France (5.1 %) and Cyprus (5.0 %), in comparison with Czechia (0.3 %), Hungary and Bulgaria (both 0.6 %) where underemployment is almost non-existent. Even though there is no striking pattern, the lowest occurrences of underemployed part-time workers tend to be in the eastern part of the EU. Outside the EU, the EFTA country Switzerland recorded a higher underemployment rate, reaching 7.1 % in 2019.

(% of total employment)

Source: Eurostat (lfsa_sup_a) and (lfsa_epgaed)

Figure 2 shows also the percentage of part-time workers regardless the underemployment in each country in 2019. Part-time work may be considered as a risk of being in a job with too few working hours, and therefore underemployment might be somehow an accompanying feature of part-time employment, i.e. high shares of part-time workers may imply high shares of underemployed workers. However, Figure 2 suggests that it is not the case for all countries.

For example, in the European Union, total employment consisted of 19.0 % of part-time workers. In the Netherlands, it consisted of 51.0 % of part-time workers, of which 7.3 % were underemployed (relatively low compared to 16.9 % for the EU). This means that although part-time work was frequently applied in this country, a high share of part-time workers was satisfied with their situation (and not wishing to work more). In Romania, for example, it was the opposite. Part-time employment in Romania accounted for 7.1 % of the total employment but among the part-time workers, almost one third (i.e. 31.2 %) were underemployed. Among others, Italy is quite close to the average in terms of part-time employment (18.9 %) and also of underemployed people among part-time workers (15.0 %).

Moreover, regardless of the recourse to part-time employment at national level, some countries recorded high shares of underemployed part-time workers among the total part-time workers. This was the situation in 2019 in Greece (65.4 %), Cyprus (45.7 %), Spain (42.6 %) and Portugal (34.4 %) where more than one third of part-time workers wished to work more hours, while, as previously mentioned, the EU-27 average was 16.9 %. At the opposite end of the scale, Czechia, in addition to a low share of part-time workers in the total employment (7.4 %), has also a low share of part-time workers (4.4 %) that were underemployed.

Focus on the potential additional labour force

Potential additional labour force stood for 7.2 % of people outside the labour force in the EU-27

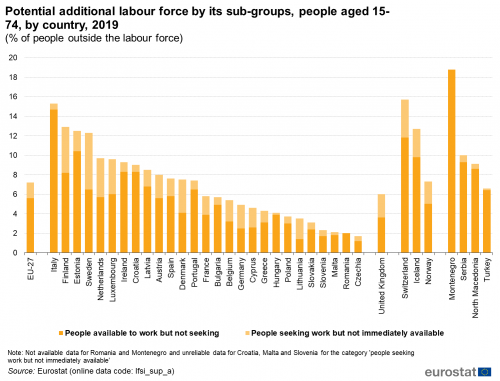

As already mentioned, the potential additional labour force consists of two subgroups. One category includes people who are available to work but do not seek it. At European level, this category accounted for 5.6 % of the total people outside the labour force in 2019. The other category is related to persons who seek work but are not immediately available to start working; this last group stood for 1.6 % of the total population outside the labour force.

All countries apart from Lithuania follow the same main pattern clearly visible in Figure 3: people available but not seeking work outnumber those seeking work but not immediately available.

Figure 3 presents the size of each subgroup as a proportion of the population outside the labour force for every EU-27 country in 2019. Both together, these categories give the potential additional labour force as a percentage of the population outside the labour force. Italy (15.3 %), Finland (12.9 %), Estonia (12.5 %) and Sweden (12.3 %) recorded more than one out of ten persons outside the labour force in the potential additional labour force. In Czechia (1.7 %), Romania (2.0 %), Malta (2.1 %) and Slovenia (2.3 %), this is the opposite situation: these countries recorded the lowest shares of potential additional labour force compared to the population outside the labour force, each below 3 %.

Inside the potential additional labour force, there are also notable differences between countries. For instance, there were exceptionally few in the population outside the labour force who were available to work but not seeking a job in Czechia (1.2 %), Lithuania (1.4 %) and Slovenia (1.7 %), whereas these are relatively more numerous in Italy (14.7 %) and Estonia (10.4 %). Also the share of those who are seeking work but not immediately available varies greatly across countries: their proportion is relatively high in Sweden (5.8 %), Finland (4.7 %) and the Netherlands (4.0 %), while they are almost non-existent in Hungary, Malta and Czechia (all three reaching 0.5 % or less).

(% of people outside the labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_a)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on the European labour force survey (EU-LFS).

Source: The European Union labour force survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between countries.

Reference period: Yearly results are obtained as averages of the four quarters in the year.

Coverage: The results from the survey currently cover all European Union Member States, the United Kingdom, the EFTA Member States of Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, as well as the candidate countries Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey. For Cyprus, the survey covers only the areas of Cyprus controlled by the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of EU-27 Member States. If data are unavailable for a country, the calculation of the corresponding aggregates takes into account the data for the same country for the most recent period available. Such cases are indicated.

Definitions: The concepts and definitions used in the labour force survey follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation.

Five different articles on detailed technical and methodological information are linked from the overview page of the online publication EU labour force survey.

Context

These three indicators supplement the unemployment rate, thus providing an enhanced and richer picture than the traditional labour status framework, which classifies people as employed, unemployed or outside the labour force, i.e. in only three categories. The indicators create ‘halos’ around unemployment. This concept is further analysed in a Statistics in Focus publication titled 'New measures of labour market attachment', which also explains the rationale of the indicators and provides additional insight as to how they should be interpreted. The supplementary indicators neither alter nor put in question the unemployment statistics standards used by Eurostat. Eurostat publishes unemployment statistics according to the ILO definition, the same definition as used by statistical offices all around the world. Eurostat continues publishing unemployment statistics using the ILO definition and they remain the benchmark and headline indicators.

Direct access to

- New measures of labour market attachment - Statistics in focus 57/2011

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - annual data (lfsi_sup_a)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - quarterly data (lfsi_sup_q)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsa_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsa_sup_edu)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and citizenship (lfsa_sup_nat)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (lfsq)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsq_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsq_sup_edu)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)

<Interactive graph to be set by unit B4:>

or

or

Introduction text

</highlight>

Direct access to

Main tables

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Database

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Dedicated section

Publications

Publications in Statistics Explained (either online publications or Statistical articles) should be in 'See also' above

Methodology

<link to ESMS file, methodological publications, survey manuals, etc.>

- Crime and criminal justice (ESMS metadata file — crim_esms)

- Title of the publication

Legislation

- Use Eur-Lex icon on the ribbon tool at the top of the statistical article to enter the year and reference of your regulation or directive.

- See example of what should be issued hereafter

- Regulation (EU) No 1013/2016

Visualisations

- Regional Statistics Illustrated - select statistical domain 'xxx' (= Agriculture, Economy, Education, Health, Information society, Labour market, Population, Science and technology, Tourism or Transport) (top right)

External links

Notes

<footnote text will be automatically inserted if reference tags are used in article content text (use reference icon on ribbon)>

[[Category:<Subtheme category name(s)>|Name of the statistical article]] [[Category:<Statistical article>|Name of the statistical article]]

Delete [[Category:Model|]] below (and this line as well) before saving!