Archive:The EU in the world - education and training

Data extracted in April 2018.

Planned article update: June 2020.

Highlights

Public educational expenditure relative to GDP among the G20 members in 2014 was highest in South Africa and Brazil, around 6 %.

In 2015, India had by far the highest pupil-teacher ratios for primary and secondary education among G20 members.

Among G20 members, Japan and Australia had the lowest proportion of young people not in employment, education or training in 2016.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (educ_figdp) and (educ_uoe_fine06) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2018.

The article focuses on education and training statistics in the European Union (EU) and the 15 non-EU members of the Group of Twenty (G20). It covers a range of subjects, including: educational expenditure, personnel, participation rates and attainment and gives an insight into education in the EU in comparison with the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

The level of educational enrolment depends on a wide range of factors, such as the age structure of the population, legal requirements concerning the start and duration of compulsory education, and the availability of educational resources.

Full article

Educational expenditure

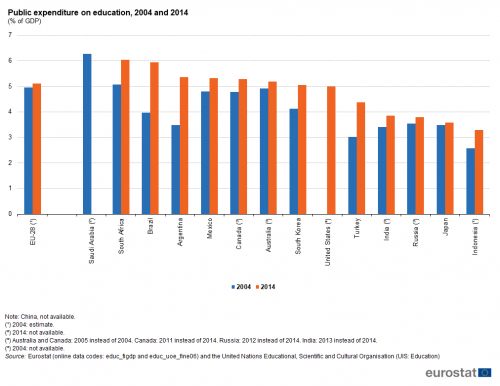

Public educational expenditure relative to GDP was highest in 2014 in South Africa and Brazil, around 6 %

Public expenditure on education includes spending on schools, universities and other public and private institutions involved in delivering educational services or providing financial support to students. The cost of teaching increases significantly as a child moves through the education system, with expenditure per pupil/student considerably higher in universities than in primary schools. Comparisons between countries relating to levels of public expenditure on education are influenced, among other things, by differences in price levels and the numbers of pupils and students, the latter influenced to a large extent by the proportion of young people in the population (see the article on population for more information).

Figure 1 provides information on the level of public expenditure on education relative to gross domestic product (GDP). Among the G20 members this was highest in 2014 in South Africa at 6.0 % and Brazil at 5.9 %; note that no recent data are available for Saudi Arabia (where a ratio of 6.3 % was recorded in 2004). In a majority of G20 members the ratio of public expenditure on education relative to GDP was between 5.0 % and 6.0 %, but was below this range in Turkey (4.4 %), falling to less than 4.0 % in India (2013 data), Russia (2012 data), Japan and Indonesia. With a value of 5.1 %, the EU-28 ranked more or less in the middle of the G20 members for this ratio. Between the two years presented in Figure 1, there was an increase in the level of public expenditure on education relative to GDP in all of the G20 members, most notably (in percentage point terms) in Brazil and Argentina.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (educ_figdp) and (educ_uoe_fine06) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

(international USD per student)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_fine02) and (educ_uoe_enra01) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

Numbers of teachers and pupils

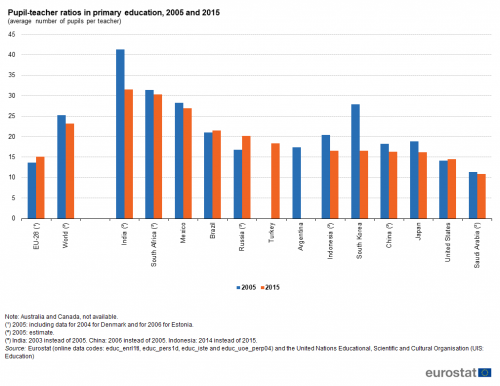

India had by far the highest pupil-teacher ratios in 2015 for primary and secondary education

Figures 3 and 4 present pupil-teacher ratios for primary and secondary education among the G20 members. These ratios are calculated by dividing the number of pupils and students by the number of educational personnel: note they are calculated based on a simple headcount and do not take account of the intensity (for example, full or part-time) of study or teaching.

Within primary education, the world average number of pupils per teacher was 23.2 in 2015. Among the G20 members, higher averages were observed in India, South Africa and Mexico, while lower ratios were observed elsewhere, in particular across the EU-28 (15.1), the United States (14.5) and Saudi Arabia (10.9). Between 2005 and 2015 the average number of pupils per teacher in primary education fell by 2.0 pupils per teacher worldwide. This pattern of falling pupil-teacher ratios was repeated in most G20 members, the exceptions being the United States, Brazil, the EU-28 and Russia.

(average number of pupils per teacher)

Source: Eurostat (educ_enrl1tl), (educ_pers1d), (educ_iste) and (educ_uoe_perp04) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

Worldwide, the average pupil-teacher ratio for lower secondary education was slightly lower than for upper secondary education in 2015 and this was also the case in the EU-28. This pattern was also apparent in a majority of the non-EU G20 members, with only South Korea, Japan, Brazil and Mexico having a higher average for lower secondary education.

Within lower secondary education, India, Mexico, Turkey and Brazil reported average pupil-teacher ratios that were above the world average (17.2), with India reporting particularly high values (30.5 pupils per teacher). Japan and the EU-28 reported averages of 12.6 pupils per teacher in lower secondary education, with China, South Africa (2010 data), and Saudi Arabia (2014 data) reporting even lower ratios.

(average number of pupils per teacher)

Source: Eurostat (educ_iste) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

Within upper secondary education, India and Turkey were the only G20 members to report average pupil-teacher ratios that were above the world average, while Canada reported the lowest average ratio (8.8 pupils per teacher). Aside from Canada, Japan, Saudi Arabia (2014 data) and Mexico had average pupil-teacher ratios for upper secondary education that were lower than in the EU-28.

School enrolment

There were more boys than girls enrolled in primary education across each of the G20 members.

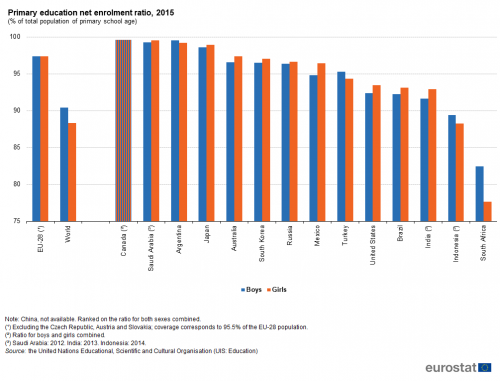

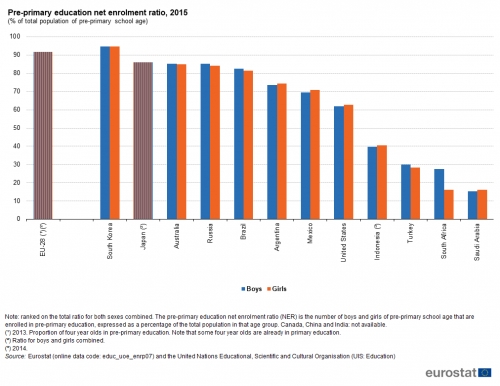

Net enrolment rates in pre-primary and primary education in 2015 notably higher for boys than girls in South Africa

Figures 5 and 6 present enrolment ratios for pre-primary and primary education. These net enrolment ratios compare the number of pupils/students of the appropriate age group enrolled at a particular level of education with the size of the population of the same age group; as such, they cannot exceed 100 % as they do not include under or over age children being enrolled in the selected level of education.

In 2015, the pre-primary education net enrolment rate was highest in South Korea at 94.7 %. Most G20 members reported pre-primary net enrolment rates that were above 60 %, although notably lower rates were reported for Indonesia (2014 data), Turkey, South Africa and Saudi Arabia. For the EU-28 a slightly different indicator is presented, showing that 91.8 % of four year olds were in pre-primary education; note that this figure for the EU should be interpreted with care as some younger children might also be in pre-primary education and some four year olds may already be in primary education. Among the non-EU G20 members, only South Africa reported a large difference (11.5 points) between pre-primary education net enrolment rates for boys and girls, with a much higher rate for boys than for girls in 2015. In Indonesia (2014 data), Saudi Arabia, the United States, Argentina and Mexico, the pre-primary education net enrolment rate for girls was higher than for boys.

(% of total population of pre-primary school age)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enrp07) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

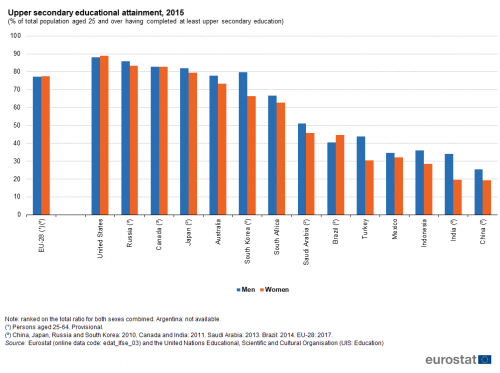

Educational attainment

Figure 7 shows the percentage of population aged 25 years and over in 2015 having completed at least upper secondary education. In the United States, Russia (2010 data) and Canada (2011 data) this share was over 80.0 % for both men and women, while in Japan (2010 data) it was also over 80.0 % for men; in the EU-28 the shares for men and women were 77.2 % and 77.5 % in 2017. Attainment rates for upper secondary educational attainment were under 40.0 % for both men and women in Mexico, Indonesia, India (2011 data) and China (2010 data), with the rate for women in Turkey also less than 40.0 %. Brazil, the United States and the EU-28 were the only G20 members for which data are available where the share of men aged 25 or over having completed at least upper secondary education was lower than the equivalent share for women. In all other G20 members attainment rates for men were higher than those for women, with the largest gender gaps — all in the range of 13-15 points — observed in Turkey, South Korea (2010 data) and India (2011 data).

(% of total population aged 25 and over having completed at least upper secondary education)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_03) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

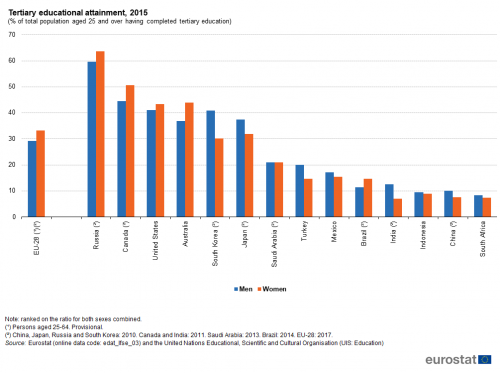

(% of total population aged 25 and over having completed tertiary education)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_03) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UIS: Education)

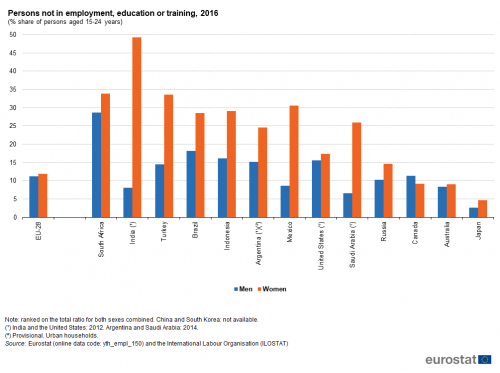

Not in employment, education or training

Japan and Australia had the lowest proportion of young people not in employment, education or training in 2016

Traditional analyses of the labour market focus on employment and unemployment, but for younger people many are still in education. As a result, labour market policies for young people often focus on those who are not in employment, education or training, abbreviated as NEETs. Factors that influence the proportion of young people not in employment, education or training include the length of compulsory education, types of available educational programmes, access to tertiary education and training; labour market factors related to unemployment and economic inactivity (being neither employed nor unemployed); cultural issues, such as the likelihood of taking on caring responsibilities with an extended family and/or the typical age of starting a family.

Figure 9 indicates the proportion of 15-24 years olds that were not enrolled in education (school or formal training) nor employed in 2016. Among the G20 members this ranged from 3.5 % in Japan, through 8.7 % in Australia, 10.2 % in Canada and 11.6 % in the EU-28 to 24.0 % in Turkey, 27.5 % in India (2012 data) and 31.2 % in South Africa. Canada was an exception among the G20 members for which data are available, as it was the only one where a larger proportion of young men were not in employment, education or training, rather than young women. By far the largest gender gap for this indicator was observed in India, where 49.3 % of young women were not in employment, education or training in 2012, compared with 8.0 % for young men; the next largest gaps were observed in Mexico, Saudi Arabia (2014 data) and Turkey.

(% share of persons aged 15-24 years)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_150) and the International Labour Organisation (ILOSTAT)

(% share of persons aged 15-24 years)

Source: Eurostat (yth_empl_150) and the International Labour Organisation (ILOSTAT)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The statistical data in this article were extracted during April 2018.

The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes worldwide — standards. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU data

Nearly all of the indicators presented for the EU have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this article and data that is subsequently downloaded. In exceptional cases, such as for enrolment rates, some data for the EU have been extracted from international sources.

G20 members from the rest of the world

For the 15 non-EU G20 members, the data presented have mainly been compiled by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, with the data for the indicator concerning the proportion of 15-24 year-olds not in employment, education or training compiled by the International Labour Organisation.

Context

Education and training help foster economic growth, enhance productivity, contribute to people’s personal and social development, and reduce social inequalities. In this light, education and training has the potential to play a vital role in both an economic and social context. Education statistics cover a range of subjects, including: expenditure, personnel, participation and attainment. The standards for international statistics on education are set by three international organisations: the Institute for Statistics of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation; the OECD; and Eurostat.

The classification used to distinguish different levels of education is the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). The version used in this publication is ISCED 2011 which has the following levels of education.

- Level 0 — early childhood education (including early childhood educational development and pre-primary education).

- Level 1 — primary education.

- Level 2 — lower secondary education.

- Level 3 — upper secondary education.

- Level 4 — post-secondary non-tertiary education.

- Level 5 — short-cycle tertiary education.

- Level 6 — Bachelor's or equivalent.

- Level 7 — Master's or equivalent.

- Level 8 — Doctoral or equivalent.

Direct access to

- The EU in the world 2018

- The European Union and the African Union — A statistical portrait — 2018 edition;

- Sustainable Development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context

- Smarter, greener, more inclusive ? Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy — 2017 edition

- Globalisation patterns in EU trade and investment

- 40 years of EU-ASEAN cooperation — 2017 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2017 edition

- Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) — A statistical portrait — 2016 edition

- Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2015 edition

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

- Key data on education in Europe 2012

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Pupils and students - enrolments (educ_uoe_enr)

- Early childhood education and primary education (educ_uoe_enrp)

- Pupils in early childhood and primary education by education level and age - as % of corresponding age population (educ_uoe_enrp07)

- All education levels (educ_uoe_enra)

- Pupils and students enrolled by education level, sex, type of institution and intensity of participation (educ_uoe_enra01)

- Early childhood education and primary education (educ_uoe_enrp)

- Pupils and students - enrolments (educ_uoe_enr)

- Education finance (educ_uoe_fin)

- Expenditure on education (educ_uoe_fine)

- Public educational expenditure by education level, programme orientation, type of source and expenditure category (educ_uoe_fine02)

- Public expenditure on education by education level and programme orientation - as % of GDP (educ_uoe_fine06)

- Expenditure on education (educ_uoe_fine)

- Education personnel (educ_uoe_per)

- Teachers and academic staff (educ_uoe_perp)

- Ratio of pupils and students to teachers and academic staff by education level and programme orientation (educ_uoe_perp04)

- Teachers and academic staff (educ_uoe_perp)

- Education and training outcomes (educ_outc)

- Educational attainment level (edat)

- Population by educational attainment level (edat1)

- Population by educational attainment level, sex and age (%) - main indicators (edat_lfse_03)

- Population by educational attainment level (edat1)

- Educational attainment level (edat)

- Education-administrative data until 2012 (ISCED1997) (educ_uoe_h)

- Education indicators - non-finance (educ_indic)

- Pupil/student - teacher ratio and average class size (ISCED 1-3) (educ_iste)

- Indicators on education finance (educ_finance)

- Expenditure on education in current prices (educ_fiabs)

- Expenditure on education as % of GDP or public expenditure (educ_figdp)

- Enrolments, graduates, entrants, personnel and language learning (educ_isced97)

- Students by ISCED level, age and sex (educ_enrl1tl)

- Teachers (ISCED 0-4) and academic staff (ISCED 5-6) by age and sex (educ_pers1d)

- Education indicators - non-finance (educ_indic)

- Youth (yth), see:

- Youth employment (yth_empl)

- Young people neither in employment nor in education and training by sex, age and labour status (NEET rates) (yth_empl_150)

- International Labour Organization ILO

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO