Archive:Statistics on small and medium-sized enterprises

Dependent and independent SMEs and large enterprises

- Data extracted in May 2018. Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: May 2019.

Authors: Aarno Airaksinen, Henri Luomaranta (Statistics Finland), George Papadopoulos, Samuli Rikama, Pekka Alajääskö, Anton Roodhuijzen (Eurostat, Structural business statistics and global value chains)

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are a focal point in shaping enterprise policy in the European Union (EU). The European Commission considers SMEs and entrepreneurship as key to ensuring economic growth, innovation, job creation, and social integration in the EU. However, in official statistics SMEs can currently only be identified by employment size as enterprises with fewer than 250 persons employed. This is a big category and encompasses enterprises with different ownership structures and varying numbers of employees and levels of economic activity. To facilitate better analysis and understanding of the heterogeneity of SMEs, the 2016 microdata-linking (MDL) project linked data from structural business statistics (SBS), international trade in goods statistics (ITGS), Business Demography (BD) and business registers (BRs). This article presents results of the 2016 MDL project for reference year 2015.

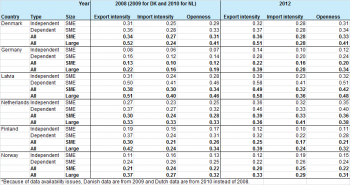

This article examines the statistical data from the MDL project, which produced linked datasets for analysing business structures and performance in a harmonised way, making cross-country comparisons possible. Nine countries participated in the 2014 MDL project. Six of those were able to break down their SMEs into dependent and independent enterprises. We analyse the SMEs (broken down in three size classes) and large enterprises in these six countries (Denmark, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands, Finland, and Norway). The data spans the years 2008 to 2012, which allows us to consider the enterprises’ evolution by size class and economic performance in terms of value added and employment. We also analyse differences in four economic sectors in all six countries: medium-high and high technology manufacturing, low and medium-low technology manufacturing, knowledge-intensive business services, and other services. Compared with previous MDL projects, a new feature is the distinction between dependent SMEs (those belonging to an enterprise group) and independent SMEs.

This article is part of an online publication on Microdata linking in business statistics.

Source: Eurostat (sbs_sc_sca_r2)

Main statistical findings

- Enterprises employing less than 250 persons are a very important part of the economy, as they represent around 99 % of all enterprises and employ an increasing number of persons.

- Most enterprises are independent and do not belong to an enterprise group; the larger the enterprise is, the larger the chance that it belongs to a group.

- Dependent enterprises are important in terms of employment and turnover, especially in these countries . Therefore, a large proportion of total growth created by SMEs can be attributed to dependent enterprises.

- Large enterprises create a higher proportion of value added in the ‘.

- Enterprises belonging to an international group also contribute highly in terms of employment and turnover especially in .

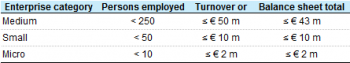

SME definition

The European Commission defines SMEs as those enterprises employing less than 250 persons that have a turnover of less than 50 million euro and/or a balance sheet total of less than 43 million euro (see Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC). SMEs are further broken down into micro, small and medium enterprises (see table 2 for details). According to the SME definition, the SME status of an enterprise which is part of an enterprise group may need to be determined on the basis of data on persons employed, turnover and the balance sheet from the whole group, and not only on data of the enterprise itself. The SME recommendation contains detailed guidelines on how much of the group’s figures should be included to determine the SME status of an individual enterprise. These guidelines are relatively complex to be fully implemented in statistical systems; additionally, for example Structural Business Statistics or other data sources of the project contain no information on the balance sheet total of the enterprises.

For these reasons, statistics often use size class information based only on the number of persons employed in the enterprise itself, without looking at the employment, turnover or balance sheet data from the group that the enterprise belongs to. However, doing this has consequences for statistics, since enterprises belonging to domestic or international enterprise group may be in a different position from independent enterprises, for example in their ability to access finance, their bargaining power, possibilities to expand to foreign markets, and various other aspects of doing business.

Why is the 'SME vs large enterprise' discussion relevant?

The growth-generating potential of SMEs has been the subject of many academic studies[1]. Although there is no general agreement in the literature on whether SMEs generate more growth than large enterprises, some recent studies[2] suggest that large enterprises are more pro-cyclical, which means that they are more affected by international business cycles than SMEs are. This fact may have implications for how different business sectors and therefore national economies behave in times of economic depression.

Recently, economic literature [3] has shifted towards analysing the role of the largest enterprises in understanding aggregate fluctuations. Trade integration, globalisation and industry consolidation have the potential to make large enterprises ever larger and thus more important in explaining business cycles and economic developments. Large enterprises can account for a sizeable portion of a country’s economic output. Therefore, if global demand for even one product falls, a country can face severe consequences that show in the aggregated measures of economic activity. This has been the case for example in Finland[4]. These microeconomic shocks may also affect the large enterprises’ networks[5]; a fall in demand can have an adverse impact on the whole supply chain, across industries and countries[6].

Although it is important to consider which enterprises generate most value added in the economy, policy makers are often more interested in employment patterns than GVA. Enterprises that generate most GVA make the economy wealthier, but those that create jobs contribute to employment creation and thus help keep the unemployment rate low. Therefore, this article analyses both the gross value added and employment patterns in the different enterprise size categories, across the six countries participating in the project.

Breaking down the population into independent and dependent enterprises

In order to facilitate better analysis and understanding of the heterogeneity of enterprises, Eurostat's 2016 micro-data linking (MDL) project linked enterprise level data for reference year 2015 from the following sources: structural business statistics (SBS), international trade in goods statistics (ITGS), business demography (BD) and business registers (BRs). One important aim of this work was to provide results broken down by the control criterion i.e. separate results for independent vs. dependent enterprises. Similar results are provided also in the exercise "voluntary data collection on SMEs". The voluntary data collection took place in 2016 (for 2013 reference year) and will be repeated during 2018.

Twelve member states and two EFTA countries participated in the 2016 MDL project. Out of these, eleven member states and one EFTA country participated in the module exploring the control dimension. These twelve countries are: Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Sweden and Norway.

This article presents results from the above eleven member states and Norway broken down into dependent and independent enterprises. Dependent enterprises are further split (where possible) into those enterprises that would still be considered as SMEs based on the employment criterion (because the entire group to which they belong employs less than 250 people) and those enterprises that are actually large ones. In the latter case, while the enterprise itself employs less than 250 persons, the group to which the enterprise belongs employs 250 persons or more. This means that the statistics still don’t completely reflect the recommended SME definition, but they do make it possible to distinguish between independent and dependent enterprises as well as those dependent enterprises that are actually large enterprises (on the basis of persons employed by the whole group).

Aggregate results from the 2016 voluntary data collection on SMEs are also analyzed in this article. These two projects demonstrate that statistics which are closer to the European Commission's SME definition can be produced by micro-data linking, and provide useful insight on the economic behavior of SMEs and large enterprises.

In this article, the following terms are used to distinguish between the different categories of enterprises:

- Enterprise with less than 250 persons employed: this is an enterprise which employs 0 to 249 persons. We do not call these enterprises ‘SME’ as there is no information on whether they also fulfill the remaining criteria of the SME definition;

- Large enterprise: an enterprise that employs at least 250 persons;

- Independent Enterprise: an enterprise which, according to the BR, is not controlled by another enterprise (neither domestic nor foreign), and at the same time, it does not control itself another enterprise (neither in the country of residence nor abroad);

- Dependent enterprise: an enterprise which, according to the BR, is controlled by another enterprise (either domestic or foreign), and/or, it controls itself another enterprise (either in the country of residence or abroad). Dependent enterprises belong to an enterprise group;

- Domestic enterprise group: a group containing enterprises which are all resident in the same country;

- International enterprise group: a group containing at least two enterprises which are all resident in two different countries.

Basic structures: employment size class breakdown in Structural Business Statistics

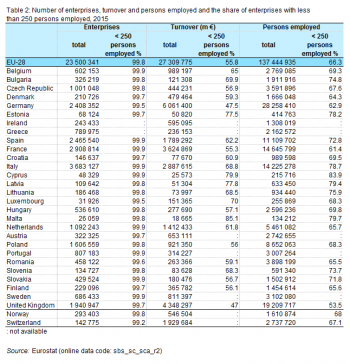

Table 2 shows the number of enterprises, turnover and persons employed for year 2015 and the share of enterprises with less than 250 persons employed. In the non-financial business economy (NACE Rev.2 Sections B to J and L to N and Division S95) enterprises employing less than 250 persons make up over 99% of all enterprises in all EU countries, Norway and Switzerland. They account for around two-thirds of total employment in the EU, ranging from 47 % in the United Kingdom to 85 % in Malta. Enterprises with less than 250 persons employed contribute about 56 % of the total turnover in the EU.

SME profiling — independent or dependent enterprises?

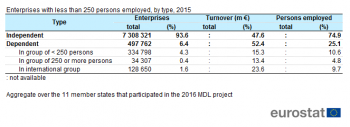

Table 3 presents the number of enterprises, turnover and employment aggregated result of the 2016 MDL project on enterprises with less than 250 persons employed for the eleven participating member states. The majority of these enterprises are independent (93.6%). In these 11 MSs, only about 500,000 (6.4%) of the enterprises with less than 250 persons employed are dependent (i.e. belong to a domestic or international group). However, these dependent enterprises have a disproportionately large contribution to turnover and employment: they account for more than half of the turnover (52.4%) and about a quarter of the employment by enterprises with less than 250 persons employed in these eleven countries. The 2016 MDL project also provided a further split of the dependent enterprises: if the number of persons employed by the entire group exceeds the threshold of 250 persons employed then the dependent enterprise should be regarded as a large enterprise following the provisions of the SME definition. Those cases are grouped separately (dependent - in group of 250 or more persons).

Most of the dependent enterprises (about 335,000 enterprises or 4.3% of the total number) belong to a group which employs fewer than 250 people. Therefore, these enterprises may still be considered as SMEs, based on the employment criterion.

About 34,000 dependent enterprises (0.4% of the total) belong to a group which employs more than 250 people. Therefore, these 34,000 enterprises are in fact large enterprises; they account for 13.4% of the total turnover and about 5% of the total employment.

The last group of dependent enterprises (about 129,000 enterprises or 1.6% of the total) are those belonging to international groups. As it is not always possible to know the size of the foreign part of the group, enterprises belonging to international groups cannot be split into those that belong to a group of less or more than 250 persons (unless the domestic part of the group already employs 250 or more persons). It can be assumed that many of those enterprises (be it foreign controlled enterprises or international group heads) will actually be large enterprises. According to Table 3, enterprises with less than 250 persons employed and belonging to international groups account for about 23.6% of the total turnover and 9.5% of the total employment. These numbers highlight the importance of enterprises belonging to international groups. As a conclusion,Table 3 demonstrates the importance of the control criterion when interpreting the data of enterprises with less than 250 persons employed.

Similar results were found in a previous study – the voluntary data collection on SMEs - in which 18 countries participated. Table 4 shows the aggregate results over the 18 countries.

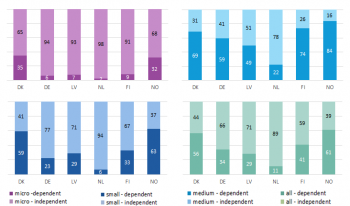

That study included also a size class analysis of the enterprises with less than 250 persons employed by splitting them into enterprises with 0 to 9 persons employed, 10 to 49 persons employed, and 50 to 249 persons employed.

The results of the voluntary data collection on SMEs show that the vast majority of enterprises with 0 to 9 persons employed (96.6%) are independent. Only 0.6% of these enterprises belong to a group that employs 250 persons or more.

More than half (54.3%) of enterprises of 50 to 249 persons employed are independent. In fact 7% of these enterprises are actually large since they belong to a group that employs 250 or more persons.

[THE text below should be replaced by the new text and figures]

Analysis of SME growth

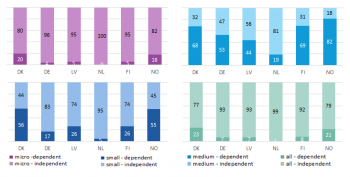

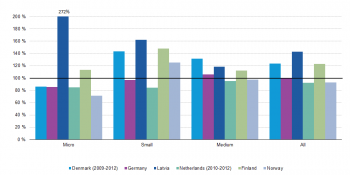

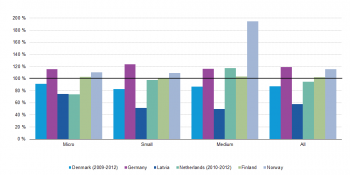

In Figures 4 and 5, changes in GVA are compared for independent and dependent enterprises in different size classes between 2008 and 2012. This is important because dependent enterprises behave differently from independent enterprises, and are often more similar to large enterprises.

In Germany and Norway, independent SMEs have grown much faster than dependent SMEs across all size categories, while in Latvia and Finland the reverse seems to be true. In Germany and Norway, dependent SMEs are at the same level or slightly lower than in 2008, with the exception of small enterprises in Norway which show a 25 % increase between 2008 and 2012. In Latvia, the micro dependent category increased by 172 percentage points between 2008 and 2012, which could be due to the intensive restructuring work and privatisation of enterprises during the 2009 recession. In Denmark, growth in 2009-2012 was concentrated in dependent enterprises, with the exception of the micro dependent enterprises, which did not grow. In the Netherlands, only medium-sized, independent enterprises showed growth. In general, the observation that dependent SMEs have become more important in the analysed business sectors could partly be explained by large enterprises having been forced to prioritise investment, find ways of reducing costs, and streamline operations. All of these activities would show as increased GVA in the dependent category.

The countries that took part in the project have different types of industries, corporate laws and business cultures, so an in depth analysis of enterprises dynamics is not possible in the scope of this article. It is clear, however, that understanding the relationships between enterprises is crucial to understanding the economic importance of the size categories. This is especially true when discussing the impact of the largest enterprises with many connections to SMEs. The statistical data we present here show that dependent SMEs are an important part of the analysed economies and have in some countries become even more important over the years analysed. This is because they create a high proportion of the value added in the SME category.

Sector-level analysis

In order to provide a deeper analysis of the observations set out in the previous section, we will now explore the economic structures present in each of the analysed countries. This section analyses the differences in four economic activity sectors based on the NACE classification, as presented in table 5.

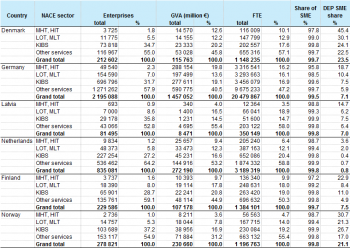

Table 6 presents the sector-level classification of the number of enterprises, GVA, and persons employed for the year 2012. The medium-high and high technology manufacturing sector generates a significant part of total GVA in Germany (18 %), Finland (14 %), Denmark (10 %) and the Netherlands (9 %). Finland has the highest proportion of GVA created by the low- and medium-low technology manufacturing sector (18 %). The proportion of GVA created by the knowledge-intensive business services sector ranges from 9 % in Germany to 17 % in the Netherlands. In all the countries, the ‘other services’ sector accounts for most GVA created, and ranges from 31 % in Norway to 55 % in Latvia.

The rightmost column in table 6 presents the proportion of enterprises that are dependent SMEs. Denmark stands out here, with a very high proportion of dependent enterprises in medium-high and high technology manufacturing (45 %) and in low and medium-low technology manufacturing (30 %). In all countries, the proportion of dependent SMEs is higher in manufacturing than in services.

Another interesting comparison is possible if one compares the proportion of GVA and of persons employed. If the percentage of GVA created is much higher than the percentage of persons employed, the sector is producing more value added relative to how much employment it needs. This is the case for example in Finland, where the proportion of persons employed in the medium-high and high technology manufacturing sector is 4 percentage points lower than the proportion of GVA created in this sector.

In the remainder of the article, after having presented the broader picture of what each country’s economy is composed of, we provide a more in-depth analysis of how dependent enterprises impact the SME category in each of the analysed sectors. In order to provide a complete picture of the situation, we also provide comparisons between large enterprises and SMEs in terms of GVA and persons employed.

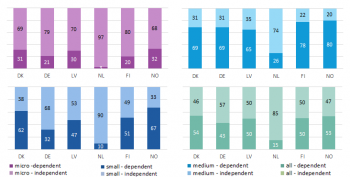

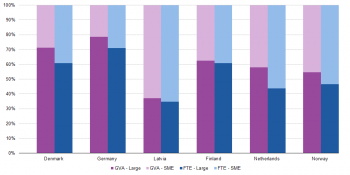

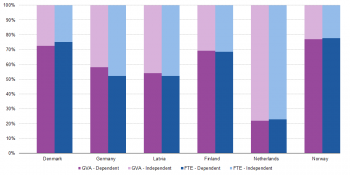

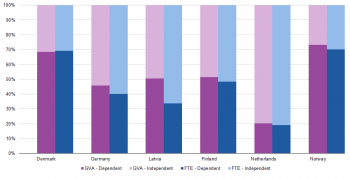

Medium-high and high technology manufacturing

Figure 6 shows that, in the medium-high and high technology manufacturing sector, large enterprises usually account for a far higher proportion of a country’s total GVA than SMEs do (except in Latvia). With the exception of the Netherlands, most SME-generated GVA seems to come from dependent SMEs (see Figure 7). The patterns are similar for the proportion of persons employed: large enterprises and dependent SMEs dominate the high-tech sector across all countries. Based on these observations, one can better understand changes in GVA created and the number of persons employed by large enterprises in different countries. For instance, one reason for the poor performance of large Finnish enterprises could stem from the performance of the medium-high and high technology manufacturing sector. When comparing GVA and FTE proportions, we see in Figure 6 that large enterprises have a higher proportion of GVA than of persons employed, which indicates higher productivity than SMEs. In Figure 7 there is not much difference between the proportion of GVA and FTE and therefore one cannot draw any clear conclusion about the difference in productivity between dependent and independent enterprises.

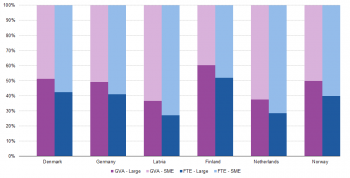

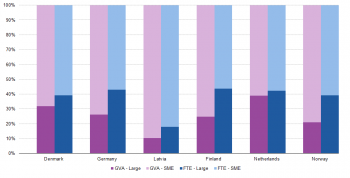

Medium-low and low technology manufacturing

The low and medium-low technology sector is composed of a roughly even proportion of large enterprises and SMEs, at least when it comes to the proportion of GVA and employment (see Figure 8). The ratio of large enterprises to SMEs is relatively low in Latvia and the Netherlands, and relatively high in Finland, in terms of both the proportion of GVA and employment. Dependent SMEs account for half or more of total SME-generated GVA in Denmark, Latvia, Finland, and Norway, as seen in Figure 9. When comparing the proportion of GVA to the proportion of FTEs, it is the larger enterprises in Figure 8 and the dependent enterprises in Figure 9 that are most productive.

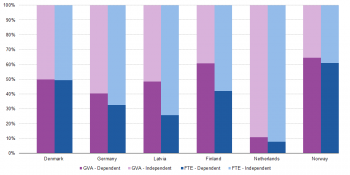

Knowledge-intensive business services

Figure 10 shows that, judging by the proportion of GVA and FTEs, the knowledge-intensive business services sector consists mostly of SMEs. Unlike in the other analysed sectors, SMEs also seem to be more productive than large enterprises. However, a surprisingly high proportion of SME-generated GVA comes from dependent enterprises; roughly 60 % in Finland and Norway, 50 % in Denmark and Latvia, and 40 % in Germany, as shown in Figure 11. This Figure also shows that the proportion of persons employed in the sector is higher for independent SMEs in Germany, Latvia, Finland and the Netherlands. It appears that, in these countries, dependent SMEs create relatively more GVA compared with how much employment they require.

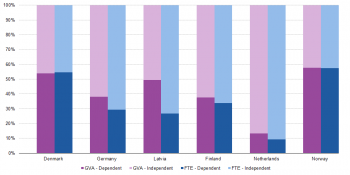

Other services

Based on Figure 12, the ‘other services’ sector consists mostly of SMEs. Therefore, a high proportion of the performance of SMEs in general can be attributed to this sector. We should bear in mind the observation from table 6, that the ‘other services’ sector is very important in the analysed economies. From Figure 13 we see that, in terms of GVA created, the SME category is roughly evenly divided into independent and dependent SMEs in Denmark, Latvia and Norway. In Germany, dependent SMEs produce 38 % of GVA, and account for only 29 % of employment in the ‘other services’ category. Latvia has a similar pattern: dependent SMEs produce 49 % of its GVA while accounting for only 27 % of employment.

Data sources and availability

In this article an SME is defined as an enterprise with fewer than 250 persons employed. New statistics on enterprises have traditionally been produced by carrying out surveys. Microdata linking presents an innovative approach to obtaining new information on the economic performance of enterprises by linking different existing statistical sources at individual enterprise level (microdata level). This approach does not require new surveys to be carried out and thus does not increase the burden placed on enterprises. Due to statistical confidentiality issues it is not possible to publish microdata on the Eurostat website. However in the future Eurostat aims at publishing aggregated tables based on microdata analysis in its database.

Context

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the backbone of Europe’s economy, providing the majority of all new jobs. The European Commission aims to promote entrepreneurship and improve the business environment for SMEs to allow them to realise their full potential in today’s global economy. The new Programme for the Competitiveness of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (COSME) will run from 2014 to 2020, with a planned budget of EUR 2.5 billion.

See also

- Business economy - size class analysis

- Microdata linking international sourcing

- Foreign affiliates employment by business function

- Entrepreneurship - statistical indicators

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Features of International Sourcing in Europe in 2001-2006 - Statistics in focus 73/2009

- International Sourcing in Europe - Statistics in focus 4/2009

- Plans for International Sourcing in Europe in 2007-2009 Statistics in focus 74/2009

Dedicated section

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

Notes

- ↑ One early contribution was the Gibrat study (GIBRAT, R.(1931): Les Inegalites Economiques, Sirey. Paris.

- ↑ An empirical example with US data: Moscarini, Giuseppe, and Fabien Postel-Vinay. 2012. ‘The Contribution of Large and Small Employers to Job Creation in Times of High and Low Unemployment.’ American Economic Review, 102(6): 2509-39.

- ↑ An example: Xavier Gabaix. The granular origins of aggregate fluctuations, Econometrica, 79(3):733–772, 05 2011.

- ↑ See the discussion in: Jyrki Ali-Yrkkö (Ed.): Nokia and Finland in a Sea of Change. ETLA B244, pp. 37–67, Taloustieto Oy, Helsinki, Finland, 2010.

- ↑ This is closely related to the discussion on dependent enterprises.

- ↑ A theoretical discussion can be found at: Acemoglu, Daron, Vasco M Carvalho, Asuman Ozdaglar, and Alireza Tahbaz-Salehi (2012), ‘The Network Origins of Aggregate Fluctuations’, Econometrica.