Archive:The EU in the world - health

- Data extracted in March 2015. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: May 2016.

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha_hf), (nama_10_gdp) and (demo_gind) and the World Health Organisation (World Health Statistics)

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind), (hlth_rs_bds), (hlth_rs_prs1) and (hlth_rs_prsns), the World Health Organisation (World Health Statistics) and OECD (Health care resources)

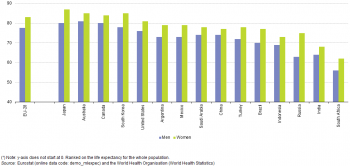

(years)

Source: Eurostat (demo_mlexpec) and the World Health Organisation (World Health Statistics)

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2015.

The article focuses on public health issues such as healthcare expenditure, provision and resources, as well as the health status of populations and causes of death in the European Union (EU) and in the 15 non-EU members of the Group of Twenty (G20). It gives an insight into health in the EU in comparison with the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Main statistical findings

Expenditure on health

Lowest health expenditure per inhabitant in South Africa

Healthcare systems are organised and financed in different ways. Monetary and non-monetary statistics may be used to evaluate how a healthcare system aims to meet basic needs for healthcare, through measuring financial, human and technical resources within the healthcare sector.

Public expenditure on healthcare is often funded through government financing (general taxation) or social security funds. Private expenditure on healthcare mainly comes from direct household payments (also known as out-of-pocket expenditure) and private health insurance.

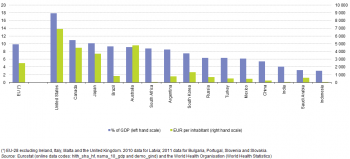

The United States had by far the highest expenditure on health relative to GDP, 17.9 % in 2012. Eight other G20 members committed between 8 % and 11 % of their GDP to health in 2012: Canada, Japan, the EU (incomplete data, see Figure 1 for details), Brazil, Australia, South Africa, Argentina and South Korea. These were followed by a smaller grouping of Russia, Turkey and Mexico (just over 6 % of GDP). China spent 5.4 % of its GDP on health with the remaining G20 members spending 4 % or less of GDP; the lowest relative expenditure was recorded for Indonesia (3.0 %).

Figure 1 also shows the absolute level of health expenditure per inhabitant — note that this is shown at current exchange rates and so does not reflect differences in price levels of healthcare among the G20 members. This shows relatively high levels of expenditure per inhabitant in the United States, Australia, Canada, Japan and the EU, whereas Indonesia, India and South Africa recorded by far the lowest levels of health expenditure per inhabitant among the G20 members.

Healthcare resources

The number of hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants in the EU-28 in 2010 was the fourth highest among G20 members

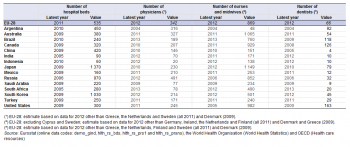

The need for hospital beds may be influenced by the relative importance of in-patient care on one hand and day care and out-patient care on the other, as well as the use of technical resources. The number of hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants averaged 535 in the EU-28 in 2011. Focusing just on G20 members for which recent data are available, this ratio for the EU-28 was the third highest among G20 members, a long way behind Japan and South Korea; the lowest availability of hospital beds relative to the size of the population was in Indonesia, with 60 beds per 100 000 inhabitants (see Table 1).

One of the key indicators for measuring healthcare personnel is the total number of physicians, expressed per 100 000 inhabitants. The variation between the G20 members in the number of physicians was relatively low in comparison with the other personnel indicators in Table 1. The highest number of physicians relative to the overall population size among the G20 members was recorded in Russia, followed by the EU, just ahead of Australia. South Africa, Saudi Arabia, India and Indonesia recorded less than 100 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants.

Among the three indicators concerning healthcare personnel, the number of dentists per 100 000 inhabitants showed the greatest variation (when taking account of their relatively low number) among the G20 members. For example, India and Indonesia recorded an average of 10 dentists per 100 000 inhabitants (in 2012), while in Canada and Brazil there were more than 100 dentists per 100 000 inhabitants (in 2008 and 2009 respectively). The average for the EU was 66 dentists per 100 000 inhabitants (in 2012).

Mortality

The gender gap in life expectancy at birth was far higher in Russia than in other G20 members

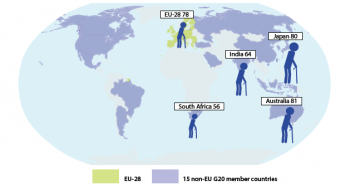

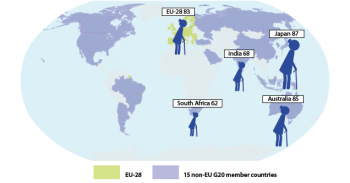

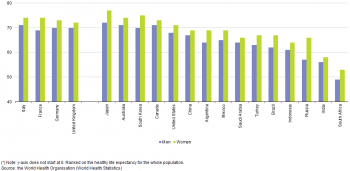

Among the G20 members, the highest life expectancy at birth in 2012 was in Japan (84 years), while in Australia, Canada, South Korea and the EU-28 life expectancy also reached or passed 80 years. In three G20 members, life expectancy at birth remained in 2012 below 70 years, ranging from 69 years in Russia and 66 years in India, to 59 years in South Africa. The relatively low life expectancy for South Africa may be largely attributed to the impact of an HIV/AIDS epidemic. In all G20 members life expectancy was higher for females than for males: the gap ranged from three years in China to seven years in Brazil, South Korea and Japan, with the 12 year gap in Russia well above this range.

In line with the data for life expectancy, the highest expected number of healthy life years at birth among the G20 members in 2012 was in Japan (75 years), while in Australia, South Korea, Canada, the four G20 EU Member States and the United States the expected number of healthy life years also reached or passed 70 years. In India (57 years) and South Africa (51 years), the expected number of healthy life years at birth in 2012 was notably lower than in other G20 members. The gender gap in terms of health life years was generally narrower than in terms of life expectancy, ranging from two to five years in all G20 members except Russia where it reached nine years.

Combining the data presented in Figures 2 and 3 indicates that healthy life (years) made up 86 % to 89 % of life expectancy at birth in most G20 members, with this proportion reaching 90 % in South Korea and 91 % in China.

Non-medical health determinants

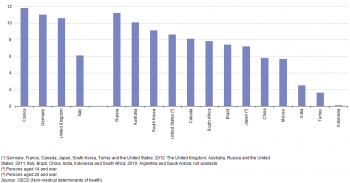

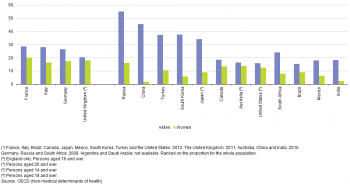

Figures 4–6 provide information on three non-medical health determinants, namely alcohol consumption, smoking and overweight/obesity. France, Russia, Germany, the United Kingdom and Australia recorded the highest annual alcohol consumption among G20 members in 2011 or 2012, at 10 litres or more of alcohol per inhabitant. The lowest average levels of alcohol consumption were recorded for Turkey, Indonesia and India, and may be influenced to some degree by the predominant religious beliefs in these countries.

Russia reported by far the highest proportion of daily smokers, just over one third (34 %) of the population aged 15 and over. Around one quarter of the population in France, China and Turkey smoked daily, with the incidence of daily smoking among the populations of G20 members dropping below 15 % in the United States, South Africa, Brazil, Mexico and India. In all G20 members shown in Figure 5 the proportion of men who were daily smokers was greater than the proportion of women. The widest gender differences were recorded in China — where nearly half of all males were daily smokers compared with just 2 % of females — followed by Russia, South Korea, Turkey and Japan. The narrowest gender differences were recorded for the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom.

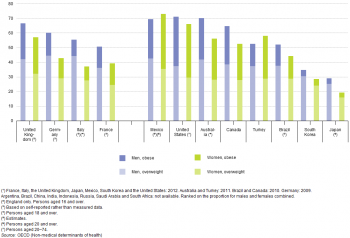

Lowest proportions of obesity in Japan and South Korea

The most frequently used measure for assessing whether is someone is overweight or obese is based on the body mass index (BMI), which evaluates weight in relation to height. According to the World Health Organisation, adults with a BMI between 25 and 30 are overweight and those with an index over 30 are obese. The data presented in Figure 6 mainly concern measured results, although for some members only self-reported data are available. Among this relatively small selection of G20 members, the highest proportions of the population that were either obese or overweight were observed for Mexico (71 %) and the United States (69 %). By far the lowest proportions were observed for South Korea (32 %) and Japan (24 %). The proportion of men who were overweight or obese was greater than the equivalent proportion of women in all G20 members shown in Figure 6, except for Turkey and Mexico. The widest gender differences were recorded in Australia and Canada.

Among the G20 members for which data are available there is far greater variability in the proportion of the population who are obese than among the population who are overweight. Japan and South Korea recorded particularly low proportions of the population that were obese, while the United States reported the highest proportions. In Turkey and Mexico there were large gender differences in the proportion of the population that were obese, with the proportions for females particularly high.

Data sources and availability

The statistical data in this article were extracted during March 2015.

The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes global — standards. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU data

Most if not all of the indicators presented for the EU have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this article and data that is subsequently downloaded. In exceptional cases some indicators for the EU have been extracted from international sources.

G20 members from the rest of the world

For the 15 non-EU G20 members, the data presented have been extracted from a range of international sources, namely the OECD and the World Health Organisation. For some of the indicators shown a range of international statistical sources are available, each with their own policies and practices concerning data management (for example, concerning data validation, correction of errors, estimation of missing data, and frequency of updating). In general, attempts have been made to use only one source for each indicator in order to provide a comparable analysis between the members.

Context

Health issues cut across a range of topics — including the provision of healthcare and protection from illness and accidents, such as consumer protection (food safety issues), workplace safety, environmental or social policies. The health statistics presented in this publication address public health issues such as healthcare expenditure, provision and resources as well as the health status of populations and causes of death.

In many developed countries life expectancy at birth has risen rapidly during the last century due to a number of factors, including reductions in infant mortality, rising living standards, improved lifestyles and better education, as well as advances in healthcare and medicine. Life expectancy at birth is one of the most commonly used indicators for analysing mortality and reflects the mean (additional) number of years that a person of a certain age can expect to live, if subjected throughout the rest of their life to the current mortality conditions.

Indicators of health expectancies, such as healthy life years (also called disability-free life expectancy) have been developed to study whether extra years of life gained through increased longevity are spent in good or bad health. These focus on the quality of life spent in a healthy state, rather than total life spans. Disability-free life expectancy is the number of years that a person is expected to continue to live in a healthy condition, in other words without limitation in functioning and without disability.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- The European Union and the African Union — 2014 edition

- Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) — A statistical portrait — 2014 edition

- The EU in the world 2014

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Pocketbook on Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2013 edition

- The EU in the world 2013

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

- Health statistics – Atlas on mortality in the European Union, 2009

Database

- Health care (hlth_care), see:

- Health care expenditure (hlth_sha)

- Health care expenditure - summary tables (hlth_sha_sum)

- Health care expenditure by financing agent (hlth_sha_hf)

- Health care expenditure - summary tables (hlth_sha_sum)

- Health care resources (hlth_res)

- Health care staff (hlth_staff)

- Nursing and caring professionals (hlth_rs_prsns)

- Health personnel (excluding nursing and caring professionals) (hlth_rs_prs1)

- Health care facilities (hlth_facil)

- Hospital beds by type of care (hlth_rs_bds)

- Health care staff (hlth_staff)

- Population, see:

- Population change – Demographic balance and crude rates at national level (demo_gind)

- Mortality (demo_mor), see:

- Life expectancy by age and sex (demo_mlexpec)

- Main GDP aggregates (nama_10_ma)

- GDP and main components (output, expenditure and income) (nama_10_gdp)

Dedicated section

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

External links

- OECD

- World Health Organisation WHO