Archive:Enlargement countries - health statistics

Data extracted in February 2019.

Planned article update: April 2020.

Highlights

In 2017, public expenditure on health relative to GDP was lower in the four enlargement countries (for which data are available) than it was in the EU.

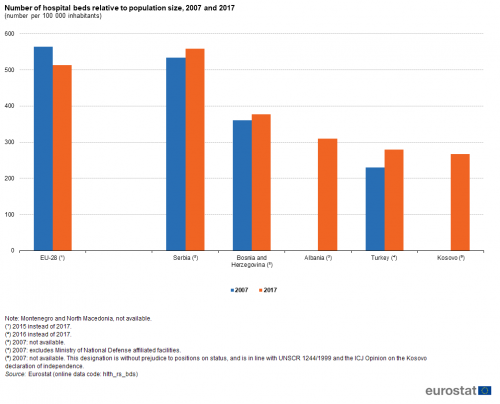

In 2016, Serbia was the only enlargement country (among those for which data are available) to record a higher number of hospital beds relative to population size than the EU average.

Number of hospital beds relative to population size, 2017

This article is part of an online publication and provides information on a range of health statistics for the European Union (EU) enlargement countries, in other words the candidate countries and potential candidates. Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Turkey currently have candidate status, while Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo [1] are potential candidates.

Statistics on healthcare expenditure and financing may be used to evaluate how a healthcare system responds to the challenge of universal access to quality healthcare, through measuring financial resources within the healthcare sector and the allocation of these resources between healthcare activities (for example, preventive and curative care) or groups of healthcare providers (for example, hospitals and ambulatory centres). This article gives an overview of health developments in the EU and the seven enlargement countries, presenting an analysis of health expenditure, health resources, hospital discharges, death rates and infection rates.

Full article

Public expenditure on health

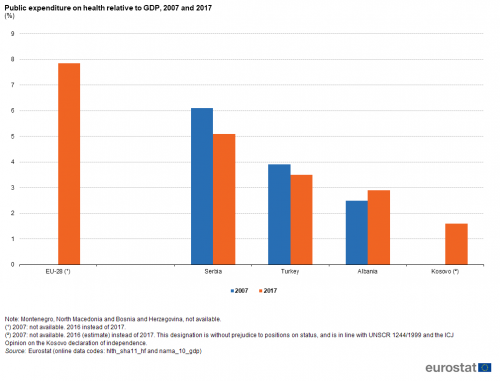

In 2016, public expenditure on health in the EU-28 was 7.9 % relative to gross domestic product (GDP). The relative weight of health expenditure was lower in each of the four enlargement countries for which data are available (see Figure 1), peaking in 2017 at 5.1 % of GDP in Serbia, with lower ratios in Turkey (3.5 %), Albania (2.9 %) and Kosovo (1.6 %; 2016 data).

Public expenditure on health relative to GDP rose by 0.4 percentage points in Albania between 2007 and 2017, whereas its relative weight contracted in Turkey (-0.4 points) and Serbia (-1.0 points). Note these developments reflect changes in both health expenditure and GDP and that falling health expenditure relative to GDP does not necessarily imply a lower absolute level of health expenditure.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_sha11_hf) and (nama_10_gdp)

Healthcare resources

Table 1 provides information on specialist healthcare personnel. Physicians need to possess a degree in medicine and are licensed to provide services to patients as consumers of healthcare, including: giving advice, conducting medical examinations and making diagnoses; applying preventive medical methods; prescribing medication and treating diagnosed illnesses; giving specialised medical or surgical treatment.

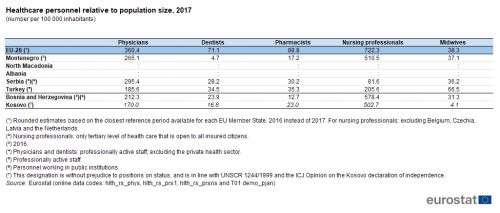

In 2016, there were an estimated 360 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants in the EU-28. Among the five enlargement countries for which data are available (see Table 1), the number of physicians relative to population size was consistently lower than in the EU-28. The highest ratios were recorded in Serbia (295 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants; 2016 data) and in Montenegro (265 physicians per 100 000 inhabitants; 2017 data).

A similar analysis for dentists reveals that the EU-28 had, on average, 71 dentists per 100 000 inhabitants in 2016. This was also higher than the latest ratios recorded in any of the enlargement countries for which data are available, with Turkey recording the highest number of dentists per 100 000 inhabitants, 35 in 2017, approximately half the ratio recorded in the EU-28.

Nursing professionals typically provide services to patients in hospitals, ambulatory care and patients’ homes: nurses assume responsibility for the planning and management of patient care, including the supervision of other healthcare workers, working autonomously or in teams with medical doctors and others in the application of preventive and curative care. In 2016, there was an average of 722 nursing professionals per 100 000 inhabitants in the EU-28. This figure was greater than the ratios recorded in any of the enlargement countries in 2017, with Bosnia and Herzegovina (2016 data), Montenegro and Kosovo each recording 500-600 nursing professionals per 100 000 inhabitants; much lower ratios were recorded in Turkey (206) and Serbia (82; 2016 data).

As with professional nurses, practising midwifery professionals plan, manage, provide and evaluate care services. Midwives do so before, during and after pregnancy and childbirth, providing delivery care for reducing health risks to women and new-born children; they may work autonomously or in teams with other healthcare providers. In 2016, there was an average of 38 midwives per 100 000 inhabitants in the EU-28. This figure was similar to the ratios recorded in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2016 data), in Serbia (2016 data) and in Montenegro (2017 data) which were in the range of 31-37 midwives per 100 000 inhabitants, while it was considerably lower than the ratio in Turkey (67 per 100 000 inhabitants; 2017 data) and many times higher than the ratio in Kosovo (4 per 100 000 inhabitant; 2017 data).

(number per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_phys), (hlth_rs_prs1), (hlth_rs_prsns) and (demo_pjan)

Hospital beds include beds for curative care, long-term care and rehabilitative care. In 2015, there were 2.6 million hospital beds available for use across the EU-28, which equated to 514 beds per 100 000 inhabitants (see Figure 2); approximately three quarters of these were for curative care, while the largest share of the remainder were beds for rehabilitative care.

Among the enlargement countries, the highest ratio of hospital beds relative to population was recorded in Serbia (559 per 100 000 inhabitants; 2016 data); this ratio was higher than in the EU-28. However, the number of hospital beds relative to population size was lower than the EU average in each of the remaining enlargement countries for which data are available: ratios of 377 and 310 hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants were recorded in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2016 data) and Albania (2017 data), while Turkey and Kosovo had similar ratios, at 280 and 267 hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants (both 2017 data).

(number per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_rs_bds)

Hospital discharges

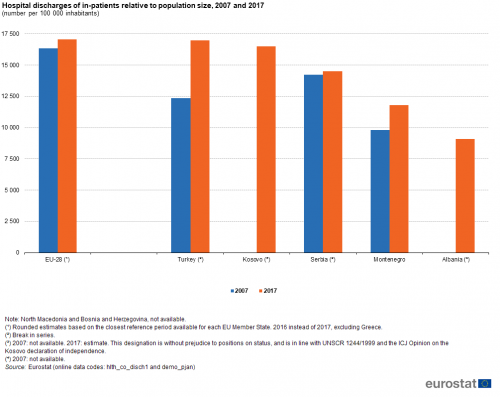

Figure 3 provides information relating to hospital discharges of in-patients; this may be used as an indicator of the level of healthcare activity in hospitals. A hospital discharge occurs when a patient is formally released after an episode of care: discharge may result from the end of their treatment, a decision by the patient to sign-out against medical advice, the patient’s transfer to another healthcare institution, or because of death. In 2016, there were estimated to be just over 17 000 hospital discharges per 100 000 inhabitants across the EU (excluding Greece). Turkey and Kosovo had similar ratios to that recorded for the EU, with 16 965 and 16 497 hospital discharges per 100 000 inhabitants in 2017. At the other end of the range, Albania was the only enlargement country — among those for which data are available — to record a ratio below 10 000 in-patient discharges per 100 000 inhabitants.

Between 2007 and 2016 (data for the latter excluding Greece) the number of in-patient hospital discharges relative to population size rose overall by an estimated 4.6 % in the EU-28; this may be linked, among others, to increased longevity and a broader range of medical treatments being made available. There was also an increase in the number of hospital discharges relative to population size in the three enlargement countries for which data are available: faster rates of change than for the EU were recorded in Turkey (up overall by 37.3 % between 2007 and 2017; note however there is a break in series) and Montenegro (20.2 %), while there was a modest increase in the number of hospital discharges per 100 000 inhabitants in Serbia (1.8 %; break in series).

(number per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_co_disch1) and (demo_pjan)

Death rates

Some of the key performance indicators for improving the health and safety of populations concern analyses of mortality due to underlying causes of death. The maternal mortality rate is defined by the United Nations as the annual number of female deaths from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management (excluding accidental or incidental causes) during pregnancy and childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration/place of pregnancy; it is expressed as a ratio per 100 000 live births.

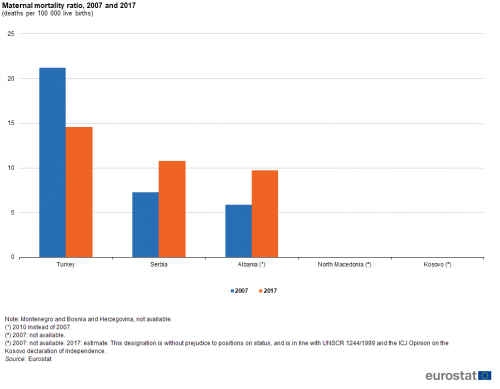

In developed economies, most women face relatively few complications during pregnancy and childbirth, as many risks have been gradually reduced over time. In 2017, the maternal mortality ratio among five enlargement countries (see Figure 4) ranged from a high of 14.6 deaths per 100 000 live births in Turkey down to no deaths in North Macedonia or Kosovo. The maternal mortality ratio fell by almost one third in Turkey between 2007 and 2017 from 21.2 to 14.6 deaths per 100 000 live births. By contrast, rates in Serbia and Albania (2010-2017) rose: it should be noted that deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth are very rare and so, particularly in smaller countries, even a difference of 2 or 3 deaths between years can result in relatively large percentage changes.

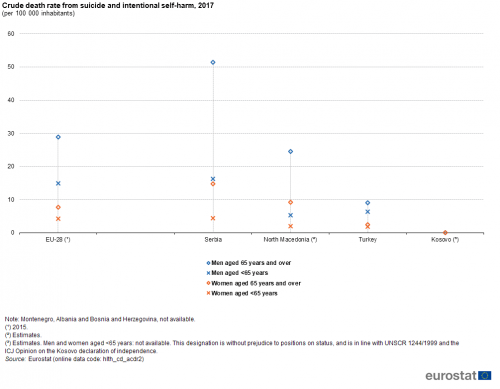

Crude death rates are defined as the ratio of the number of deaths to the average population during one year; as with many other health indicators, these ratios are expressed per 100 000 inhabitants. In 2015, the EU-28 crude death rate from suicide and intentional self-harm was 15.0 per 100 000 male inhabitants aged less than 65 years, which was approximately 3.5 times as high as the corresponding rate for women aged less than 65 years (4.3 deaths per 100 000 female inhabitants). An analysis by age reveals that EU-28 crude death rates from suicide and intentional self-harm were considerably higher for men aged 65 years and over, 28.9 deaths per 100 000 male inhabitants; this was 3.8 times as high as the corresponding rate among women aged 65 years and over (7.7 deaths per 100 000 female inhabitants).

Information is available for four of the enlargement countries for 2017: this reveals that crude death rates from suicide and intentional self-harm were consistently higher in Serbia (than in the EU) for both sexes and both age groups identified in Figure 5; the difference was most notable for people aged 65 years and over. Crude death rates from suicide and intentional self-harm in North Macedonia were broadly in line with those recorded for the EU-28 among people aged 65 years and over, while much lower death rates were recorded for both men and women aged less than 65 years. The lowest crude death rates from suicide and intentional self-harm were recorded in Turkey and Kosovo (no information available for the latter in relation to people aged less than 65 years).

(per 100 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_cd_acdr2)

Infection rates

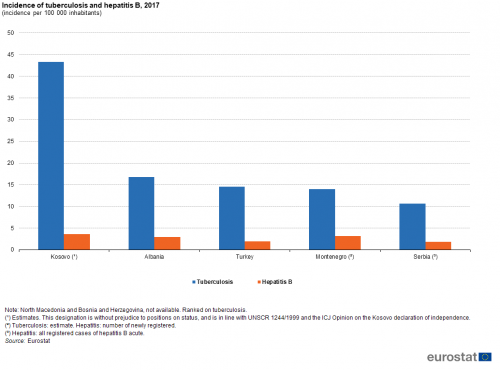

This final section analyses the incidence of two specific diseases: tuberculosis and hepatitis B.

In 2017, the incidence of tuberculosis was highest among enlargement countries in Kosovo (43 cases per 100 000 inhabitants). This was a far greater incidence than elsewhere, as the next highest incidence rate was recorded in Albania (17 cases per 100 000 inhabitants).

Among the enlargement countries, Kosovo also recorded the highest incidence of hepatitis B (3.6 cases per 100 000 inhabitants in 2017), while Montenegro (newly registered cases only) and Albania also recorded rates of at least 3.0 per 100 000 inhabitants.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Data for the enlargement countries are collected for a wide range of indicators each year through a questionnaire that is sent by Eurostat to partner countries which have either the status of being candidate countries or potential candidates. A network of contacts in each country has been established for updating these questionnaires, generally within the national statistical offices, but potentially including representatives of other data-producing organisations (for example, central banks or government ministries). The statistics shown in this article are made available free-of-charge on Eurostat’s website, together with a wide range of other socio-economic indicators collected as part of this initiative.

Health statistics measure both objective and subjective aspects of people's health. They cover different kinds of health-related aspects, including key indicators on the functioning of the health care systems and health and safety at work. These statistics cover a range of subjects, including: health expenditure, health resources, hospital discharges, death rates and infection rates.

In December 2008, the European Parliament and the Council adopted Regulation 1338/2008 on Community statistics on public health and health and safety at work. It was designed to ensure that health statistics provide adequate information for all EU Member States to monitor Community actions in the field of public health and health and safety at work. It lists five domains for which implementing regulations specifying (in detail) the list of variables and methodological aspects were to be developed, including:

- health status and health determinants: Regulation (EU) No 141/2013 on European Health Interview Survey;

- health care: as covered by Regulation (EU) No 141/2013 and Regulation (EU) 2015/359 on statistics on health care expenditure and financing;

- causes of death: Regulation (EU) No 328/2011 on statistics on causes of death;

- accidents at work: Regulation (EU) No 349/2011 on statistics on accidents at work;

- occupational diseases and other work-related health problems and illnesses.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

Context

Each EU Member State is responsible for its own health system. As such, EU policy in this area is designed to support and complement national actions and address common challenges, by providing a forum for exchanging best practices. EU policies seek to protect and improve the health of EU citizens, support the modernisation of health infrastructure, and improve the efficiency of Europe’s health systems.

Health statistics are used to monitor the EU’s health strategy — Investing in health — and the EU’s health programme (as established by Regulation (EU) 282/2014), as well as their contribution to the Europe 2020 strategy and sustainable development goals (SDGs). These statistics have a key role to support the development of evidence-based policies both nationally and within the EU. They also serve as a basis for calculating indicators to monitor some aspects of social protection and social inclusion and a set of indicators known as the European core health indicators (ECHI).

While basic principles and institutional frameworks for producing statistics are already in place, the enlargement countries are expected to increase progressively the volume and quality of their data and to transmit these data to Eurostat in the context of the EU enlargement process. EU standards in the field of statistics require the existence of a statistical infrastructure based on principles such as professional independence, impartiality, relevance, confidentiality of individual data and easy access to official statistics; they cover methodology, classifications and standards for production.

Eurostat has the responsibility to ensure that statistical production of the enlargement countries complies with the EU acquis in the field of statistics. To do so, Eurostat supports the national statistical offices and other producers of official statistics through a range of initiatives, such as pilot surveys, training courses, traineeships, study visits, workshops and seminars, and participation in meetings within the European Statistical System (ESS). The ultimate goal is the provision of harmonised, high-quality data that conforms to European and international standards.

Additional information on statistical cooperation with the enlargement countries is provided here.

Notes

- ↑ This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence

Direct access to

Other articles

- Enlargement countries — statistical overview — online publication

- Statistical cooperation — online publication

Publications

- Statistical books/pocketbooks

- Key figures on enlargement countries — 2017 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2013 edition

- Leaflets

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2019 edition

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2018 edition

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2016 edition

Database

- Health status (hlth_state)

- Health determinants (hlth_det)

- Health care (hlth_care)

- Health care expenditure (SHA 2011) (hlth_sha11)

- Health care resources (hlth_res)

- Health care activities (hlth_act)

- Disability (hlth_dsb)

- Causes of death (hlth_cdeath)

- Health and safety at work (hsw)

Dedicated section

Methodology

- Candidate countries and potential candidates (ESMS metadata file — cpc_esms)

External links